The wave of the massive Nirbhaya protests prompted the government to set up 36 One Stop Centres (OSCs), one for every state and UT, on a pilot basis in 2015. Today, there are 819 operational OSCs across the country. This is the country-wide list.

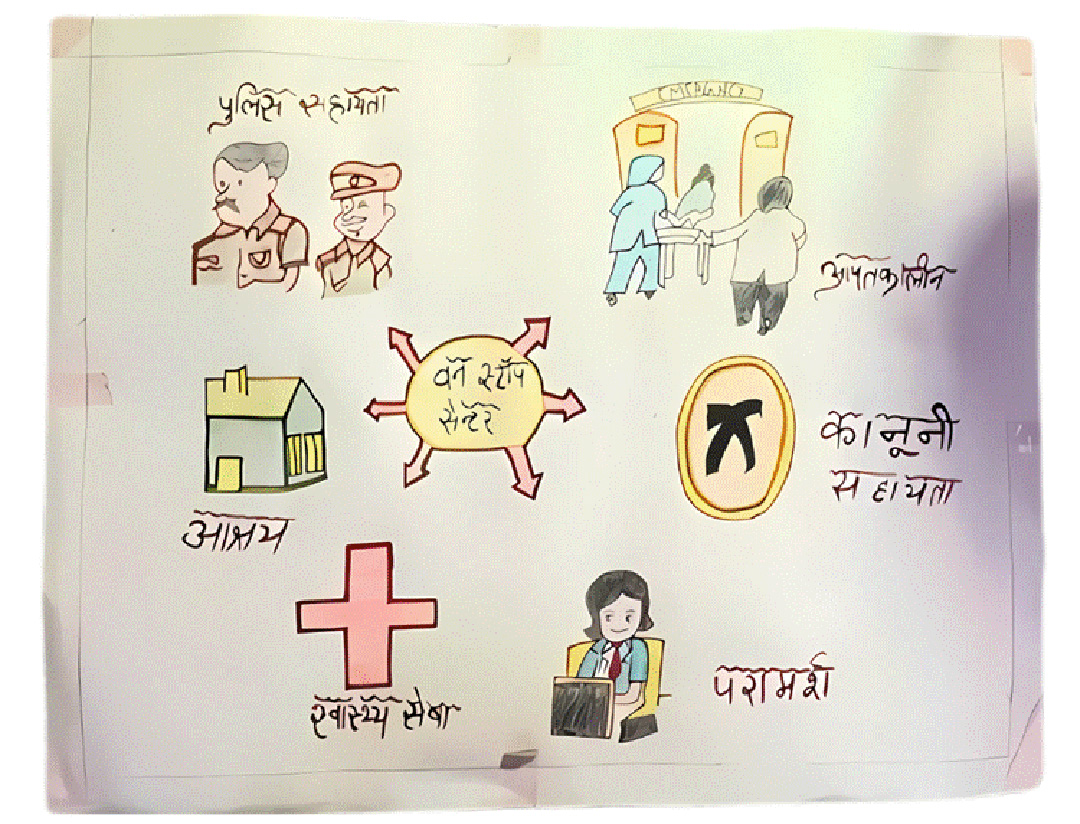

A One Stop Centre is meant to integrate victim-survivor’s access to different mechanisms of justice such as police, hospitals and courts, while also providing emergency shelter and psycho-social counselling. These services are facilitated through contractual front-line workers like caseworkers, counsellors and advocates. Security personnel and multi-purpose staff further ensure that the shelter space is clean, secure and has food to eat

The primary assumption behind creating such a space was that women could have, as the name suggests, a one-stop recourse after facing violence — without navigating multiple institutions for justice. I sought to understand whether this was true, by closely looking at OSC’s promise of integrated services.

Researching violence against women in India is complex. One reason is the lack of comparable and reliable data on its prevalence. The National Crime Records Bureau is meant to release the Crime Against Women data every year. But it has not been released since 2022. Further, this data only considers reported crimes and not women’s experiences of violence; the latter may be far more, as some estimates suggest. The National Family Health Survey, which records women’s experiences of violence, only considers violence in private (or domestic) spaces, not public spaces.

My colleagues and I had studied how under-reporting of violence in existing crime statistics perpetuates a vicious cycle of under-investing in shelter-based safety schemes (like OSCs) in India. OSCs, which seemingly offer a one-stop solution to the problem, should ideally bridge the gap between women’s experiences of violence and its reporting. This, in turn, should encourage recognition of the high prevalence of violence and increase government investment in spaces like OSCs.

But would simply increasing resources (more funds, more OSCs) enable women to seek justice? Would more resources also enable the OSC’s front-line workers (subsequently referred to as first-responders) to comprehensively address victim-survivors’ needs?

When my fieldwork for this study began, I was influenced by the push and pull of my own positionality.

My toolkit for the first-responders at the one stop centre involved several structured and semi-structured questions, which meant they would have to answer (boring) questions like, “What is your role at the centre?”/ “How many hours do you work?”/ “What kind of cases have you seen the most?”, et cetera. More importantly, sitting with me and answering these questions would have carried a time cost; when first-responders are not engaging with a victim-survivor, they are busy filing registers. The administrative burden is magnificent.

At the OSC in Delhi where I did my fieldwork, the caseworker handles 18 registers!

As per the OSC’s administrative data (per a Right to Information response from Delhi Government I received on 1 April, 2025), it has assisted 1,602 women between 2019 and 2024. Between 2023 and 2024, the number of women assisted declined by 4 per cent (from 422 to 405).

Consequently, I decided to change my approach. I decided to become a fly on the OSC’s figurative wall. This proved to be far more effective than asking the first-responders straight-jacketed questions about the OSC’s functioning. In academic terms, I decided to embrace non-participant ethnography; not directly engaging with the first-responders but observing their day-to-day activities and interactions at the OSC. Through these observations, I was better able to locate how victim-survivors navigate justice through such State-sponsored setups.

I narrate a particular day’s account of my fieldwork at a one stop centre in Delhi. I chose this account for two main reasons. One, it involves all primary first-responders (caseworker, legal advocate and psycho-social counsellor). Second, it spotlights the victim-survivor’s negotiation with justice, a function of OSC’s capacities.

***

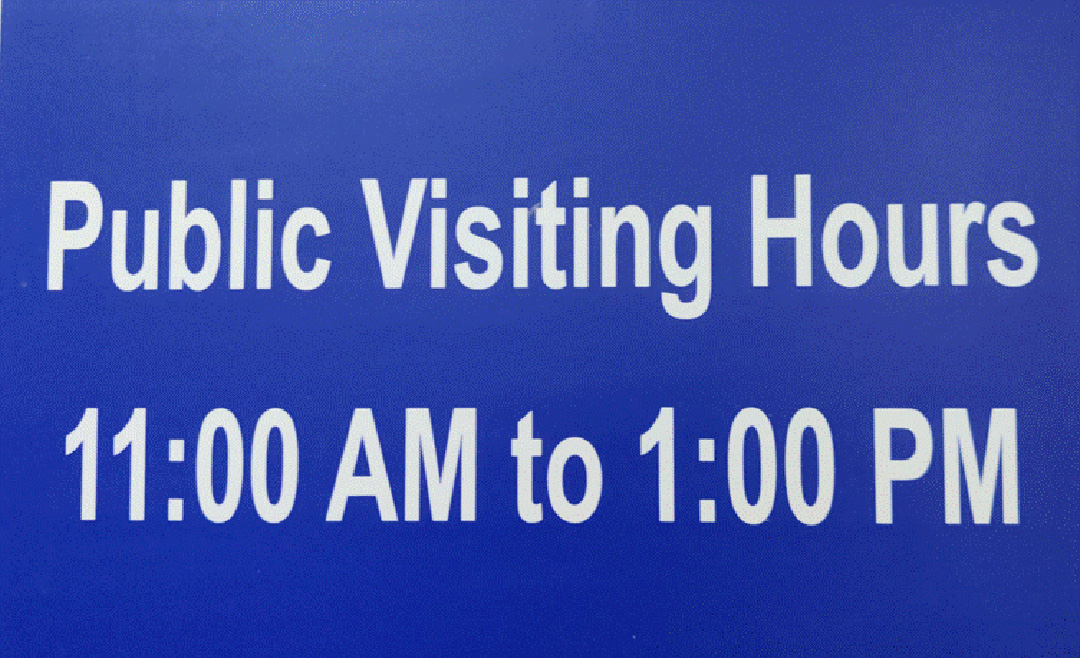

It was a cold, hazy, and dim Friday afternoon in Delhi. I was advised to come to the centre in the afternoon, as the legal advocate would be present after 2 pm.

This OSC is situated inside a bureaucrat’s office complex, near some of Delhi’s elite women’s colleges, and has a school close by. Like every other day, there were several people, both inside and outside the perimeter of this office.

Inside the bureaucrat’s office complex, the OSC is designated two rooms; one where the administrator and the IT officer sit, and another room specifically repurposed as an emergency shelter. The space is clean. It has five beds, an attached washroom and a kitchen, plenty of indoor lighting, but poor natural lighting and ventilation, as windows are sealed shut. The counsellor and caseworker sit in the same space, attached to the emergency shelter. The interlocution with victim-survivors happens in this space too.

Everyone was winding up lunch before the advocate arrived. The advocate’s position of authority was palpable, as the caseworker immediately stood up from her chair and offered it to the advocate. We briefly chatted, and it wasn’t long before Suman (name changed for confidentiality) arrived. She looked at the bunch of us and sat on the empty chair beside me. I gestured at the caseworker asking if I should move, but she said I could continue sitting at my spot.

Suman was a 181 case. An erstwhile standalone scheme for providing round-the-clock emergency response for women in distress, the Women’s Helpline (or 181 helpline) was recently integrated with OSC services.

36 years of age, Suman had spent her life filing complaints.

“Jamaana yahi nikal gaya (My entire life has gone into this)”. She lived with her family and had separated from her husband, but the divorce was not yet finalised. Her daughter, four years old when Suman left, lived in the marital house.

When Suman was still living with her husband, she had sought police help for domestic violence. The couple had received 10-15 counselling sessions from them, but the husband went back to his ‘old ways’, said Suman to the advocate’s interjection about the situation with her husband.

Entering the OSC, Suman felt disoriented. She said it was because her natal family mixed “nasha” (intoxicants) in her food. She must also apply makeup before stepping out of the house, because they did “kata piti” (cuts) on her face. The advocate, meanwhile, pulled out her designated OSC register and began asking her some personal details — her name, address, father’s name, et cetera — when Suman interrupted, “Aap likho matt, bas sunn lo (Don’t write, just listen to me).” The advocate said she has to write because it is protocol. Suman continued,

“Ghar pe torture karte hain. Sab jhoot bol rahe hain. First floor pe phek diya bhai ne. Husband bolta hai ki beti ko court se lo. Parents jaane nahi dete. Ab beti nahi pehchaanti mujhe kyuki paanch saal ho gaye. (Everyone tortures me at home. They are all lying to me. They have moved me to the first floor of the house. Husband says I should approach the court if I want to take my daughter back. She doesn’t even recognise me because it has been more than five years since I left).”

It was up to us — the observers and responders — to connect the pieces of the puzzle.

The advocate repeated her questions often, and Suman took a few moments to respond. Suman also said, “Aap nahi samjhe? (Did you not understand?)”, to explain herself better or when she believed that we were not comprehending her.

Suman seemed frustrated and tired. A month ago, she had been to the police to file yet another complaint against her family. The advocate asked for proof of the recent complaint. Suman showed them a photo of the recently filed complaint on her phone. The advocate read the complaint and asked what her family had done to her “private parts” mentioned in the complaint. Suman began pointing to different parts of her body. She pointed to her head with three stitches; her hair, which, she said, they keep cutting; her arm, which had burn marks; her face and her slippers. She looked at me while pointing to her slippers.

The caseworker and counsellor were taking notes, just like I was. They interrupted only for clarifications. The advocate, who was the primary interlocutor, then asked whether she was receiving maintenance from her husband, because according to the law, the parents are not obligated to give her anything. “After marriage, the wife is the husband’s responsibility. DLSA can send a notice to the husband,” the advocate said to her in Hindi.

The District Legal Services Authority (or DLSA) is a district-level court that provides “free and competent legal service to the weaker sections of the society”. The advocate is a representative from the DLSA. She cannot take up Suman’s case herself, but can advise Suman on her next steps. A “competent” advocate would be appointed to her case upon visiting the nearby district court, she told Suman.

The advocate advised that Suman shouldn’t file a domestic violence case against the parents, but sue for property

To which Suman said, “Par zinda nahi rahungi toh property ka kya karungi? (But what will I do with the property if I am not alive?)” The advocate then said that she should file for both. She said Suman should carry her identity documents like Aadhaar card, passport photo, et cetera, when visiting the court.

The caseworker asked Suman to write her complaint in detail. All victim-survivors at the OSC must submit a written complaint as part of the response process. In this case, since Suman was literate, the caseworker asked her to write it herself. Suman says, “Maine YouTube pe dekha aise hi kuch bhi nahi likh sakte (I have seen on YouTube that I cannot just write anything)”. She requested the caseworker and advocate to write her complaint based on everything she had said so far. They responded by saying that she must do it herself, but they will help her.

Suman kept saying the police hadn’t done anything about her situation. Her investigating officers kept changing. She was jeered at every time she visited the police station,

“Paagal bolenge toh paagal hi rahoongi. (If they keep calling me mad, I will remain mad.)”

The advocate advised that she should mention this experience in court too.

But this was not the only time Suman faced institutional apathy. When she had previously reached out to the 181 helpline, she was asked to leave her house and sleep at the neighbour’s instead. Would that have helped, I wondered. The suggestion surely seemed to frustrate Suman.

She continued talking while writing her complaint, joining the long list of formal records Suman has participated in creating for the OSC.

Her exhaustion and desparation for justice were no surprise. Even after experiencing this apathy, the only resolution at play was to navigate another bureaucratic maze. Another complaint to file at the court (as the legal advocate from the OSC was only counselling her, not representing her) too. And another set of individuals to demand justice from.

In the middle of these interactions, the counsellor looked at me and mouthed, “She is mentally disturbed.” I did not know how to react and resumed listening to Suman.

Suman’s husband had once come to meet her at her parents’ house. Hearing this, the advocate was pleased and told the caseworker that they should instead ask the husband to visit the OSC for counselling. Suman added that when she visited her husband a few days later at his house, he didn’t let her in because of her sister-in-law. She had always suspected an affair between them.

“Gaadi mein haath daal raha hai. Ghar pe daalo na bhabhi ke saamne. (He touched me in the auto. Why can’t he do this at our house, in front of the sister-in-law?)”. She said she had removed his hand. The advocate asked why Suman did that. Suman said it was because they were separated. “Self-respect sirf male ki nahi, female ki bhi hoti hai. (Men have self-respect, but so do women)”, she replied.

The advocate and caseworker concluded that his “male ego” was hurt and, hence he wasn’t letting her back in.

It had been more than an hour since Suman arrived. I felt uneasy. I knew I couldn’t directly engage with Suman due to my capacity as an observer. I stayed quiet, even though she was sitting right next to me. But by being in that room, wasn’t I somehow already a part of her journey of seeking justice?

The advocate had arrived at a final decision. She concluded that Suman must file for a property matter against her parents and demand maintenance from her husband. Domestic violence was a consequence of these primary issues and, therefore, should be her secondary complaint.

“Aap mere favour mein kya karoge? (What will you do for me?)” The advocate replied that the court will decide, because only the husband can be compelled to pay maintenance. The OSC would only counsel her family. Before Suman left, she asked for everyone’s names. The advocate also left sometime after that.

Both the advocate and caseworker said to me that such cases were routine. When they were new at their jobs, these details of women narrating their experience of violence would bother them a lot. But the devil lies in these details, I thought. The caseworker continued, “Iske parents ekdum sajjan honge (Her parents will put up a very innocent front.)” I asked the counsellor what she had meant when she signalled that Suman was mentally disturbed. “Did you notice how she kept going back and forth with her statements?” the caseworker asked rhetorically.

***

Several questions and reflections persist. All of them point to the convoluted layers of response and (in)ability to seek justice.

How does Suman feel every time she has to narrate her story?

In most cases, by the time a victim-survivor arrives at this OSC, they have already approached the police, undergone medico-legal case procedures at the nearest hospital, and shared a detailed account of their experience of violence at every step. As an interlocutor connected to these sites, the OSC maintains documentation and contacts of the interactions and people involved. According to the administrative data, all victim-survivors had received psycho-social counselling at this OSC in 2024; however, only 1 per cent received police assistance, 2 per cent received medical aid and 24 per cent received legal counselling.

Then how is the OSC, through its one-stop promise of accessing justice, doing things differently?

How well is it helping the victim-survivor identify her needs?

I asked the counsellor. In her practice, she gives the victim-survivor time to open up and make her aware of her rights. “But they often lie,” she said. And the statements at multiple sites (police, hospital, et cetera) act as proof of coherence and verification. “She will tell the truth to someone at least . We will know,” added the counsellor.

Hence, the process assumes that women are lying.

The lack of implicit and explicit trust manifests on both sides. It is no wonder then, that most cases of violence are not reported, or are severely under-reported, as I had highlighted at the outset of this article.

However, Suman’s experience suggests that she may still be hopeful. But it doesn’t mean that she wasn’t careful. She wanted to know how the OSC would help her, perhaps because her other attempts at justice — especially with the police — were unsuccessful. She was wary of writing complaints, and the previous time she had consulted the 181 helpline at the OSC, the outcome was less than satisfactory. One of the first things she had said upon entering the OSC was that she simply wanted everyone to listen to her. She did not feel heard.

What if Suman had arrived with fresh injuries? How would they assist her then?

In Delhi, as on 28 February 2025, 22 OSCs have been approved, of which only 50 per cent are currently operational. One exists in each of its 11 administrative districts.

While most OSCs operate out of a public health setting, that is, inside a district’s designated hospital, the one where I carried out my fieldwork did not have a hospital of its own. According to the guidelines, in such a scenario, a hospital should exist within a two-kilometre vicinity. The nearest hospital to this OSC is almost four kilometres away. Until November 2024, the OSC did not have its own vehicle either.

In urgent cases, the caseworker takes the victim-survivor to the hospital at her own expense.

The centre, further, has not had any money since March 2024. The staff is operating without salaries. Everyday expenses are being taken care of by the centre’s administrator. She, however, has faith the funds will arrive; it always does, whenever it does. “We operate like the police,” she added, suggesting that they cannot stop operations just because there is no money.

The caseworker and counsellor have an educational background in social work and psychology. They understand why their work is important. And so, they accept longer-than-usual hours and missed weekends. But like the other services rendered in the bureaucrat’s office complex, victim-survivors at the OSC too are being treated as mere scheme beneficiaries. This, as we saw in Suman’s case, attracts a distance, an apathy, inhibiting a victim-survivor-centric response. There were moments when active listening was thwarted because documenting the evidence of her presence was priority.

OSC’s functioning, therefore, should also reckon with how systemic gaps undervalue and compromise first-responders’ critical care burden, and seep into their ability to respond.

Adequate and timely funds are further critical to supporting response through first-responders. Earlier, funds came directly from the central government to the district account. Since 2022, however, it has been routed through the state government. OSC used to be a standalone scheme. It was repackaged under Mission Shakti’s Sambal sub-scheme in 2021. This, in essence, has meant that fund transfers happen at two stages (central and state) instead of one, as was the case before.

Now, only when 87.25 per cent of funds are utilised across the 11 OSCs, the next tranche is released by the state government, explained the OSC’s administrator.

Several OSCs are unable to spend because there are not enough cases. In her OSC, however, they have a lot of cases (at least 40 per month), so the need for timely funds is pressing.

What if another victim-survivor arrived for legal counsel? How would the one advocate attend to them? And why can’t a woman be further accompanied to the court?

The OSC is only meant to provide legal advice, not representation — though the legal counsellor is mandated to be present all days of the week, as per the guidelines. At this OSC, however, an advocate from the nearest District Legal Services Authority visits every Friday. Advocates assigned to the OSC also keep changing, the caseworker had told me.

Victim-survivors are thus asked to visit the centre on Fridays. The caseworker and counsellor set up these interactions; they schedule accordingly, depending on the case. If the need for advice is urgent, victim-survivors are asked to go to the DLSA directly. The OSC staff does not accompany them.

Currently, there is only one caseworker and one counsellor (the counsellor is an external hire and is present on-site 15 days of the month), as opposed to two caseworkers and one counsellor mandated to be present every day.

Hence, even if they wished to accompany the victim-survivor to the court, they wouldn’t be able to, amid short-staffing and high administrative burden.

Further, taking her to the hospital for immediate assistance would also pose a challenge for similar reasons, as this OSC was already outside the recommended vicinity of a hospital. The counsellor’s primary assessment of Suman was that she had mental health issues, but it is almost impossible to verify this assessment or provide contextualised support. In fact, the caseworker admitted that the OSC actively rejects such cases because they do not have the capacity to engage with such victim-survivors. This is unlike what I later saw during my fieldwork at the Mumbai OSC, which was located inside a hospital and had a larger number of trained and equipped staff to deal with such cases.

An OSC’s existing informal rules— a certain routine way of engagement and receiving cases (mostly through the police) — are stifling the envisioned one-stop access to justice for victim-survivors. Instead, it takes pride in functioning like the police (as the centre’s administrator admitted), an institution which women distrust.

***

Suman had left about 15 minutes before I did. The atmosphere, both inside and outside the office complex, had changed. With the onset of winter, the sun had already set. I could not spot any women on the street. I could hardly spot anything, or anyone known, including the guard outside the complex premises, who was used to my presence and smiled at me every time I had visited the OSC before. I could not spot the multiple cars and bikes parked along the office complex. Even the street vendor right outside had shut shop.

I tried booking an auto. No rides were available. I walked further away from the office. My pulse rate fastened, as I noticed some men standing on a very empty street connected to the highway I was heading towards to find my ride back. I could only imagine how Suman must have felt. Or how the caseworker and counsellor feel every time they step out of the office. How must the night-duty security guard and multi-purpose helper — who are all women too — feel?

The caseworker and counsellor must walk back to the Metro station together, I thought. I wished I had left with them. Would I go back to the OSC to say I am feeling unsafe? I smirked at my thought, not only because an OSC’s ambit is restricted to the aftermath of violence, but also because I had just witnessed Suman’s bargain for justice. The institutions meant to support Suman are shortchanging her. They have deviated from their intended promises.

Note: I disclosed my position and sought informed consent from all participants before the proceedings began.