The easiest thing to tell a woman in a violent marriage is to just leave. But is leaving always that simple? From financial vulnerabilities to a loss of kinships, to a turbulent clash of hope and fear, to a complex interplay of love and desire, the decision to not leave and stay in a violent marriage is not simple. In these snapshots, caseworkers – who stay in violent marriages themselves – take us through their own samjhautas with themselves. How they make their own space, recover their sense of self-worth, find ways of coping with and make meaning of the biggest contradiction of their lives.

A caseworker from Sahjani Shiksha Kendra, who has spent years working on gender-based violence, takes us through her own samjhauta of staying in a violent marriage – with the backdrop of all the samjhautas women across the generations have made.

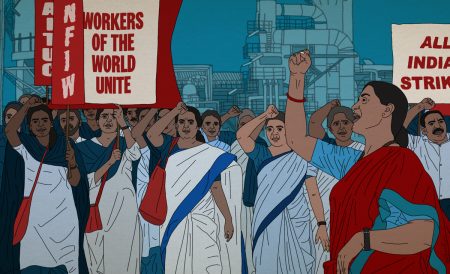

The Third Eye worked with 12 caseworkers in rural and small town Uttar Pradesh, and through a process that included immersive writing, theatre-based pedagogies and year long workshops, the caseworkers became the lexicographers of The Caseworkers’ Dictionary of Violence.

When it comes to decisions, it is other people who make them for women. Whereas when it comes to samjhautas, women are compelled to make them.

When I was young, I closely observed the situation of women in my family – my Ma, Dadi, Chachi, Bua. I saw the samjhautas they were making in their lives. Each had her own kind of struggles and compromises made in the course of her life. As a young girl, I tried to absorb these ways of making samjhautas.

My grandmother was very beautiful, tall, fair, healthy, and was no less than a fearless heroine of her time. She lived at her parents’ home and everyone called her Jijji. She was bold and was not scared of anyone. Sixty years ago, she brought up her six children all on her own. She was the only child of her father. When she was young, she thought that if she took care of her parents, she would inherit the land. And so, she returned from her husband’s home to her parents’. (My grandfather—her husband—was indifferent and didn’t mind leaving her at her parents’ place. He did not take any responsibility for her or for their children.)

We are very much a country dominated by men and their decisions. So, my grandmother’s father sold off all of his property during his lifetime thinking that since he had only a daughter and no son to inherit his property, it made no sense to hold on to his land. Even after this, my brave grandmother carried on with determination, breaking down barriers to work, driving a bullock cart day and night.

My father had two brothers. When people failed to push my grandmother to do something, they’d complain to my father saying, “Your mother talks too much. She does not listen to anyone.” I remember sometimes hearing my father denigrating my grandmother. He’d say, “My mother has ruined my reputation, and on top of that, I have a wife who is a fighter cock. And these three daughters have come to ruin my home.” I used to feel terrible hearing this.

My father got his way all the time by bitterly complaining and accusing the women of dominating his home. My mother would say, “You keep speaking ill of me but what have my daughters done to you that you speak so ill of them?” He would reply, “You are a woman. I am the one who earns, that is how you and your daughters survive. You are a snake who will only leave after poisoning me.” My mother just couldn’t bear to hear all this. She’d shout, “If I am a poisonous snake, I would not have given birth to five of your children. Nor would you have any heirs.”

Ma had five siblings: four sisters and a younger brother. She was always worried about her parents’ home, as her father had passed away and she was the only one who was married. She supported her sisters when they got married. My father earned a decent living at that time. Whenever Ma’s family needed money or anything, she was promptly there.

My Nani too would say about my mother, “She is not my daughter, she is my son. Even if I had a son, he wouldn’t have supported me like my daughter supports me.” Ma always wanted to see her siblings and her mother happy. She was devoted to them and loved them. My Mama and Mausi too loved us dearly.

As time passed, Ma’s responsibility towards her parents’ home reduced, and the three of us grew up. Every now and then, Ma and Papa fought over one thing or the other. Ma often threatened to kill herself saying she was going to jump into the well or poison herself. We, the three sisters, just sat beside her. Then one day I was 17, my younger sister 16 and the youngest 15. My brother was 10. That day, Ma told us that when all of her daughters are married, she would kill herself. We saw all these things; watching and listening we learned that this was how to survive within our families.

I was married that year. Along with me, my younger sister was also married to my younger brother-in-law. Our baraat arrived on the same day and we both arrived as dulhans in the same sasuraal. My sister, all of 16, didn’t even know the significance of marriage. She was just excited about dressing up. When I was crying over leaving my home, she consoled me saying, “Didi, why are you crying? See, I am coming with you!” The in-laws laughed and remarked, “One sister cries and the other laughs.” I tried to make her understand. “We are now in our sasuraal. Do not talk or laugh unnecessarily.” But since she was the youngest, everyone loved her too.

I was the third daughter-in-law, the sajli. My husband used to get epileptic attacks which used to distress me. He also did no work. After we had a child, our financial situation was quite pathetic. Since we were four daughters-in-law, my mother-in-law and father-in-law didn’t give us any special attention. They divided the property in four parts and everyone started living on their own. Everyone’s husband earned except mine. Neither was my husband willing to let me work. He was scared that I might leave him as I was educated. When we were down to our last rupee, I made a decision to go out and do something.

I began working in a dal mill. But my husband did not stop hitting me. He’d hit me and then I would go to work. Every day. A lady at work understood my situation and said one day, “Beta, very sensible. You are maintaining the respect of both your homes, your sasuraal and your maika.”

I felt really happy on hearing this: that in some ways, people around me respected me because I was bearing all this beating without saying anything to anyone.

My husband humiliated me every day and demanded, “Give me the money you got.” At times, he turned up at my work place and threatened me, “Do not come home after five…” Whenever I went to work, I made sure I was home before five. Sometimes, I got late because there was a lot of work. My heart raced then. I was scared at the possibility that he could come to my workplace and abuse me, shaming me in front of everyone.

One day, my mother-in-law didn’t give me any fuelwood for fire and said, “Get your own wood.” I left my son at home in order to get some wood not very far from home. My mother-in-law said to my husband, “I don’t know where she went, leaving her child behind!” I was walking home, carrying the wood when I saw my husband coming towards me. His eyes were bloodshot with rage. Before I could say or do anything, he slapped me so hard on my face that I felt as if the world had stood still. A silence descended within me and at that moment, I decided to kill myself. I was abused at home and a few people at work and in the fields had seen me being beaten before, but this time it was on the road. So many people had seen my husband hit me. On that day, he insulted me in front of everyone. For whom should I live and why? Rather than suffer this oppression daily, it was better to leave this world.

At home, I was intent on suicide. Just as I was pegging a rope through a hook, my son grabbed it from my hands. Right then my husband entered the room, took that very rope and beat me with it. He beat me so much and so hard that by the end of it, my entire body was marked by the lashings.

Even today, when I think about these things or then try and write about it, those scenes appear before my eyes. My heart wells up, my eyes fill up, but I still gather myself together to continue writing.

Those days, there was no one there to help me. Because when you are hit by poverty, even your near and dear ones cut off all ties with you. I have observed this. But that same woman at the dal mill told me one day, “You are educated; there is a women’s sansthan at Mehroni, why don’t you try for some work there?” I went to Sahjani Shiksha Kendra. In my application I explained my situation. I was interviewed and then started working in the residential school.

My husband started torturing me even more saying, “Even the district magistrate does not work at night the way your job requires you to.” I listened to all these taunts but did not resign. I had found a job that I had liked and it was after eight years that I was holding a pen in my hands. I didn’t want to lose that pen now again. That was almost a decade ago.

Till today, I remember the songs we used to sing in the training sessions. One went thus:

Dariye ki kasam, maujaun ki kasam,

Ye dana bana badalega

(But I swear on the river, on the waves of the river,

this warp and weft of judgement will change.)

When we sang this song, I felt as if we were promising to change our world and would only be satisfied by bringing about that change. Every stanza of the song energised me and filled me with passion.

Sometimes, I feel a lot of mental tension and cannot think about what is right or wrong. Whenever I feel like that, I busy myself at work. I meet many women through my work and I meet them with an open heart. I share my life’s experiences with them and also listen to theirs. They share their problems and we often crack jokes. And the whole day passes quite nicely.

In the past, I cursed my fate every time my husband beat me and cried remembering my parents’ home. Now, I have slowly emerged from these things.

I go to work, come home and give my husband his food. I do not think too much about it. I make my own decisions. I know that I have to live in this home but I also keep some money for myself. I buy things that I like, even a mobile phone for myself. How I would like to have my own home constructed. Now, I think about these things too. I think for my own self.

While working as a caseworker, I often tell women, never mind if you cannot leave the house, but do not constantly think about your husband. I ask them to think about themselves.

I try to be their support system and tell them that they can call me anytime and share their feelings with me. Even their likes and dislikes.

After all that has happened, I am still with my husband. I do not have one, single answer to this question but there are many reasons. My children are now at a marriageable age. I am still caught up with the thought of what will people think. There is no support for me from my parents’ home. My husband is sick often and gets epilepsy attacks and I have to care for him too. I am also scared that it is a sin to leave my husband in this condition.

Now, slowly and steadily, I can easily get out of my home; I am working and the violence has also reduced. But still my husband curses and abuses me. He hits me occasionally.

My children do support me, especially my daughters. My son often argues with me and asks me, “How much do you earn? Why don’t you tell me where you spent the money?” But when he sees his father beating me, he stands up for me.

My daughters love their parents, both their Ma and Papa. They are attached to their Papa. They feel that it is their Papa who has brought them up. I do not ever say that they should hate their father but at times I feel that my children should think about how much their father beats their mother. Even though I have been somewhat successful in getting myself out of the alleys of violence, insult and shame, I still find myself tied to the idea of samjhauta. The truth is that it is women’s lives that get trapped and caught in this elaborate web of reasons.

Translated by Bhumika Aggarwal with inputs from the TTE Team