In October 2019, Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal introduced free bus travel for women in Delhi, adding free fare to a long history of gender-based public transportation policies. While social media forever boils over in heated response, feminist scholarship on gender and public transit helps clear the steam. It allows us to reflect on why we need these policies, what motives lie behind their implementation, and how we wish to move forward.

According to Dr. Robin Law, it was a pathbreaking set of research articles in the 1970s that first introduced the idea that women’s experiences of public transit differ from that of men. Subsequently, she says, two parallel research areas emerged. One of these chose to focus on fear and sexuality. From Leoti Baker in New York of 1903 to Nazreen in present-day New Delhi, physical safety is after all, the most visible and widespread concern for women in public transport.

18-year-old Nazreen*, from Old Delhi, tells us of the day she poked a man with her safety pin to stop him groping her on the bus. “Ghar se dar darke niklana padtha hain hum ladkiyon ko (We girls have to live in fear every time we leave home),” she says, adding that she always wears her bag in front now, covering her chest, to prevent such incidents.

As research scholar Meher Soni points out, it either places responsibility on women themselves, or leaves it to the paternalistic state to protect them in the public sphere – assuming in both cases, that women are always safe in the privacy of their homes.

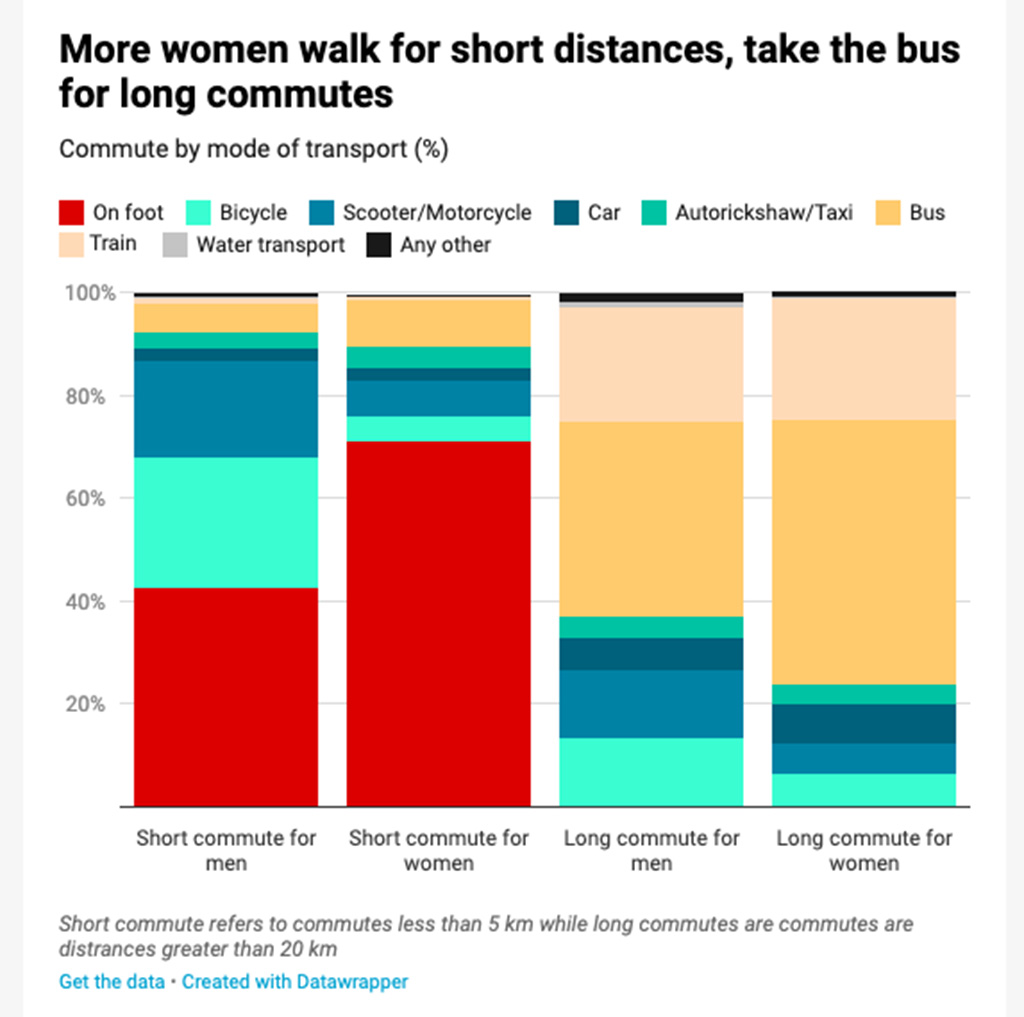

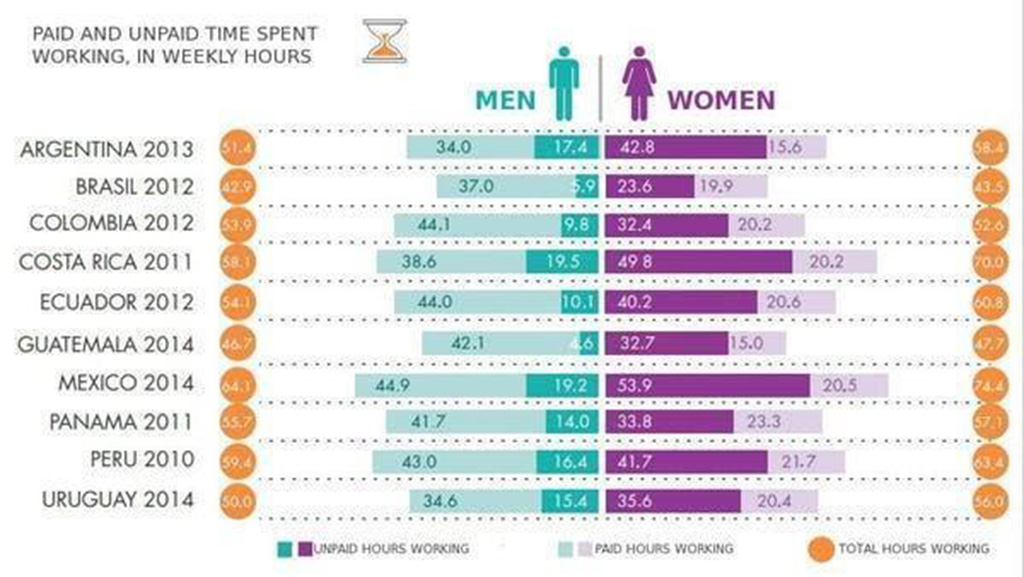

The focus now shifts from gendered experiences of public transport to gendered patterns of use. While men tend to travel long, straightforward round-trips to their workplace and back for instance, women tend to conduct several short trips a day, often more on unpaid labour responsibilities than men.

The Delhi government’s decision to make bus travel free for women could also be seen as a response to the decline we are witnessing in the rate of Female Labour Force Participation (FLFP). According to journalist Bansari Kamdar, “Among its South Asian neighbours, India now has the lowest FLFP, falling behind Pakistan and Afghanistan, which had half of India’s FLFP in 1990.”

But how is a declining FLFP connected to public transportation? Visualise it as a chain of events that we’re working through backwards. As Shinzani Jain observes, one of the commonly identified reasons for a decline in FLFP is lack of employment opportunities for women. Lack of employment opportunities in turn, is generally attributed by feminist economists to three factors:

- The gender pay gap – that makes women more likely to leave their jobs than men.

- Time spent on unpaid labour – such as household chores, childcare and care of elderly members in the family.

- The need to find work closer to home – due to unpaid labour responsibilities, safety concerns and the fact that women have less time to spare on long-distance travel.

As a result, women tend to look for work that is part-time, flexible, and closer to home. Ticketless bus travel allows them to make multiple trips a day and increases the chances of them taking up employment.

Speaking of work during lockdown, Gulafza from Khajuri explains how she had to wait in queues every morning at the bus stop. One day, the bus driver announced a new rule that only four women could enter at a time. Male passengers on the bus readily agreed with him, making it impossible for the other waiting women to disagree. Luckily for Gulafza, she was second in line. Upon entering the bus however, comments began to flow.

“Look at these women,” said one uncle, “they’ll wait hours for a bus just because they want everything for free. The money they save, they’ll waste on beauty parlours for sure!”

These remarks have become a regular feature of bus travel for women in Delhi.

Frustrated and tired of keeping quiet, Gulafza turned at last and said, “You’re absolutely right, uncleji, we do spend on parlours. But have you not seen us anywhere else? If a woman saves even 1000 rupees per month on travel, she ends up spending it on gents like you and the children of gents like you!”

Recalling the way she’s seen men spend most of their income on cigarettes and alcohol instead of household expenditure, she added, “If the government made it free, it’s because they know who spends carefully and who doesn’t!”

From the back of the bus another man joined in, “Sure, sure, women are the ones running the country and we’re just sitting around doing nothing!” But Gulafza was done responding to provocation.

“Ab uncleji, hum kya kahe,” she sighed with a smile, “aap sab kuch bol diya toh?” [Now uncleji, what can we say? You’ve already said it all!]

What we’ve read so far of feminist pedagogy on gender and public transit is just the tip of the iceberg. Dig a little deeper and we get to the layer of scholarship that attempts to critically access existing policies, paying careful heed to the structural forces that drive them.

Take Gender Mainstreaming for instance. An idea proposed to help de-gender the public transportation sector by actively including women staffers and decision-makers, it sounds fair enough.

Yet, as (perhaps unintentionally) pointed out by Olurinu Jose in a 2018 conference co-hosted by the World Bank, gender balance is not always a moral imperative but often a business decision too. Especially, she says, since women workers never want to strike.

A most blatant sign of them lacking the agency and resources needed to demand rights, this begs the question—are we hiring women because we want their input or because their already disadvantaged backgrounds make them easier labour to exploit than men? Factors of race, caste and class further complicate this question, as evidenced best in the ever-increasing degree of female workers in the informal sector.

As feminist and civil rights leader Angela Davis says, “I have had a hard time accepting diversity as a synonym for justice. Diversity is a corporate strategy. It’s a strategy designed to ensure that the institution functions in the same way that it functioned before, except now you have some black faces and brown faces. It’s a difference that doesn’t make a difference”. Ultimately therefore, a big setback with gender mainstreaming is the way it merely replaces one gender identity with another while leaving the underlying system of gender unquestioned.

A second example is scholarship on the manner in which gender segregation of public transit reinforces the “essentialities” of gender. It turns metros into portable purdahs, takes shitty male behaviour as an inevitable given, makes general public spaces effectively “male” public spaces, and finally, leaves little room for individuals who are gender non-conforming.

Yet, like the andarmahals and zenanas of affluent households in history, or the women-only hilltop parks in Tehran, segregated spaces are those that paradoxically both restrict women and liberate them from male surveillance.

Be it Bengaluru, Delhi, Chennai or Mumbai, there is usually comfort to be found in the ladies’ compartments of public transit. As captured so wonderfully by Anushree Fadnavis, it’s a space that allows women to do as they please, at whatever odd hour, in whichever big city.

This puts us in a funny place. On one hand, we know how problematic segregation is, and yet on the other, we enjoy it. It’s a guilty pleasure now to yearn for the ladyland of Sultana’s Dreams.

In 1662, mathematician Blaise Pascal envisioned the world’s first public transit system, making carriages that had until then been purely for private use, accessible to all Parisians. It wasn’t long however, before the rich banned “soldiers, servants and unskilled workers” from the system. Nearly four centuries down the line, the “public” continues to be defined by heavily restricted access. From the hostile design of public bathrooms for gender minorities and people with disability, to the “strong discrimination” against women from the fishing community using public buses in coastal Kerala, examples are not hard to come by.

This brings us to a significantly more exciting layer of theory; that of feminist geography and spatial justice. Or alternatively, research built on the idea that the spaces we occupy are constantly shaping and shaped by the social, political and economic aspects of human society.

This approach is held firmly together by the Marxist-inspired belief that all citizens have a political right to public space, part of which includes the right to independence, freedom and pleasure.

It’s only once a year that Alisha gets to travel, leaving home in Bareilly to spend summer at her uncle’s house in Delhi. Always by train, always by the window where it’s windy and beautiful. The last time she went however, someone had already taken her place. “But I’m younger than you!” the 19-year-old cried, trying to convince the lady that it was her most favourite seat in all the world.

“You’ve bought this seat from your house or what?” retorted the aunty, proving to be just as stubborn.

Alisha sat for a while and sulked. Suddenly, hearing the chaiwala approach, she had a brainwave: “Okay, okay, would you like something to eat? I’ll buy it for you.” But the aunty didn’t want chai. In a little while, a chipswala appeared. “Chips, chips!” cried Alisha in desperation but chips, said the aunty, are for children.

Looking longingly at the window, Alisha remembered the times she put her hand out, feeling the wind push it up and down, side to side, whizzing past the trees and lamp-posts. Trains move at such incredible speeds, no?

They arrived at Moradabad station. The smell of hot samosas wafted past their window. Alisha caught the aunty’s look. Finally! A plate of samosas and just like that, the window seat was hers. The trip to Delhi was worth it at last.

Mobility, as demonstrated by the 1991 Pudukottai cycle campaign for women, is fundamental to establishing a sense of self-reliance and independence. In other words, the thrill of truly adulting.

“I feel my most effective when weaving my way through an underground station,” observes author and illustrator Lizzy Stewert. “I can dart around tourists and families on museum trips to the ticket gate where I tap my card and feel effortlessly capable. The ticket gate is often where I think, ‘Here I am. An adult woman in London, who’d have known?’ Which is a deeply uncool thought, but a true one.”

But is belief in a political right to public space enough to overcome the multi-layered restrictions of access to it? Recent feminist developments in the city of Barcelona tempt me to say yes. This broadens our horizons beyond women, bringing other gender and sexual minorities, people with disability, senior citizens, children and those from varied class, caste and racial backgrounds into the picture. While free public transport might be one step in that direction, the plethora of possibilities ahead are exciting to envision and the journey of course, has only just begun.

*All the quotes in this piece are from two story making sessions conducted at different learning centres of Delhi and UP under Parwaz Adolescent Centre for Education (PACE) programme by Prarthana from Nirantar Trust on the theme of mobility and transportation with out-of-school girls.

Further reading, i.e., a few beautiful and bizarre things I found while researching for this piece:

- Anti-sexual harassment campaigns held across the world include: campaigns by a bus commuters community, meeting to sleep in Bengaluru, teaching women to cycle in Pudukkottai, organising nights for women in Bogota, holding slogan-writing competitions in Delhi, enforcing the Stop on Request Programmes in Bhopal, putting up cat-calling posters in France, role-playing scenarios in Thailand, and wildest of all, installing “penis seats” in the Mexico Metro.

- Discussion of Nazanin Shahrokni’s book at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

- Lecture by Ana Falu on gender perspectives in urban planning.

- Please Mind the Gap – a film on gender shot almost entirely on the Delhi Metro.

- Podcast by Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy on Feminist Urbanism.

- Podcast by 99% Invisible on the design and accessibility of public restrooms.

- Sultana’s Reality, an interactive history of women and learning in India.

- Photo essay by S. Basu on women, public spaces and loitering.