Home » Uncategorized » Domestic Workers Narrative -Photo Story

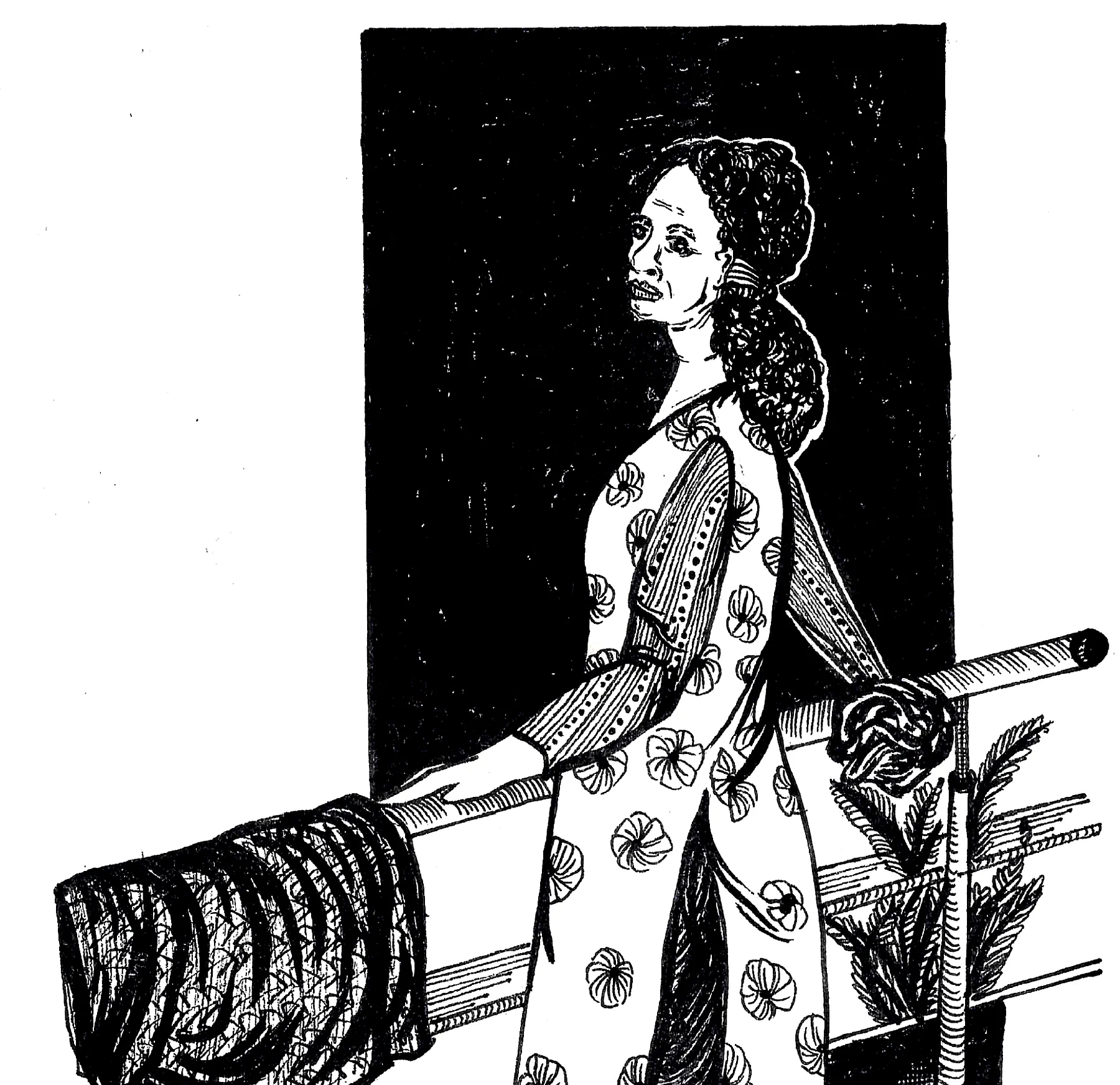

India’s suburbs have witnessed a residential construction boom over the last few years, often through land acquisition by the state, which was handed over to private builders. This, in turn, has led to many condominium complexes and townships being built in the suburbs, with forevermore coming up. These complexes essentially function in similar ways; multiple towers with apartment units that are individually owned, with a range of common spaces and amenities for the residents. They usually boast a luxurious clubhouse, pools, gyms, and several gardens between different buildings. Most often, grocery shops, salons, bakeries, and even doctors’ clinics are inside the premises. Unambiguously, they function like mini republics of their own.

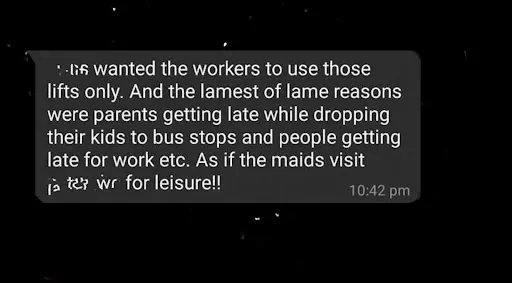

However, extensive and varied labour goes into keeping these complexes running, such as housekeeping, gardening, security, waste collection, etc. Several services, for instance, waste collection and disposal and security are handled by the builders or contracted out to an agency, which has its own labour force with its own caste dynamics and land displacement history. However, services like domestic work or car cleaning are solicited at the private unit/household level. While there will certainly be overlaps in these various workers’ access, mobility, and treatment, certain specificities also need contextual inquiries. The ambit of this piece is limited to the figure of the domestic worker, and even within that, it is non-exhaustive. This piece is particularly interested in the relationship the body of the domestic worker has with the master body of modern living.

Domestic workers perform (grossly underpaid) reproductive labour1 for individual household units within these gated complexes and, most often, are from lower caste, lower class, religious minority, and migrant backgrounds. This piece also primarily takes into consideration workers who are not ‘live-in maids’, that is, they do not reside in the household they work in, and it only briefly considers workers who live in the households. Those too, require their specific inquiry.

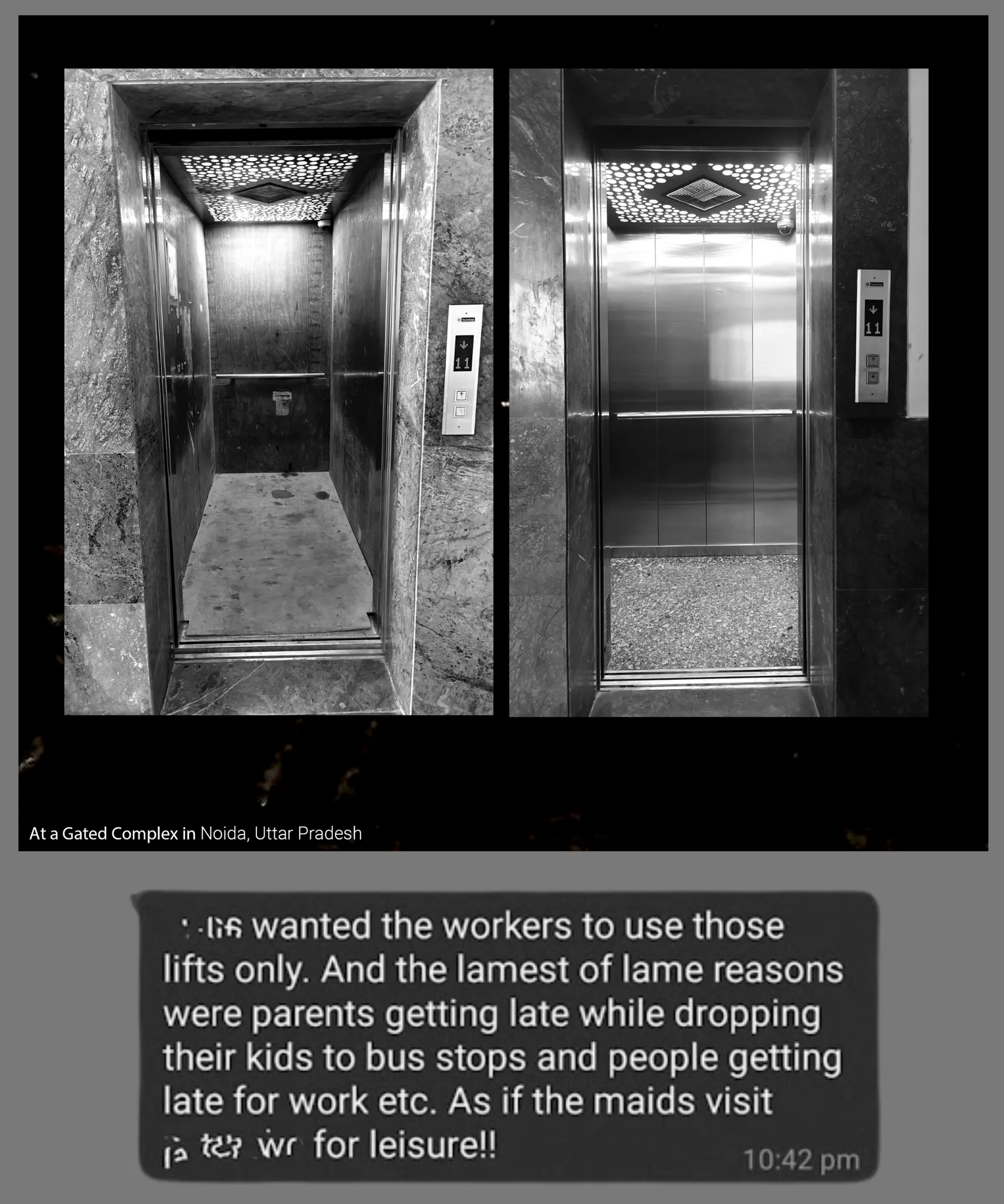

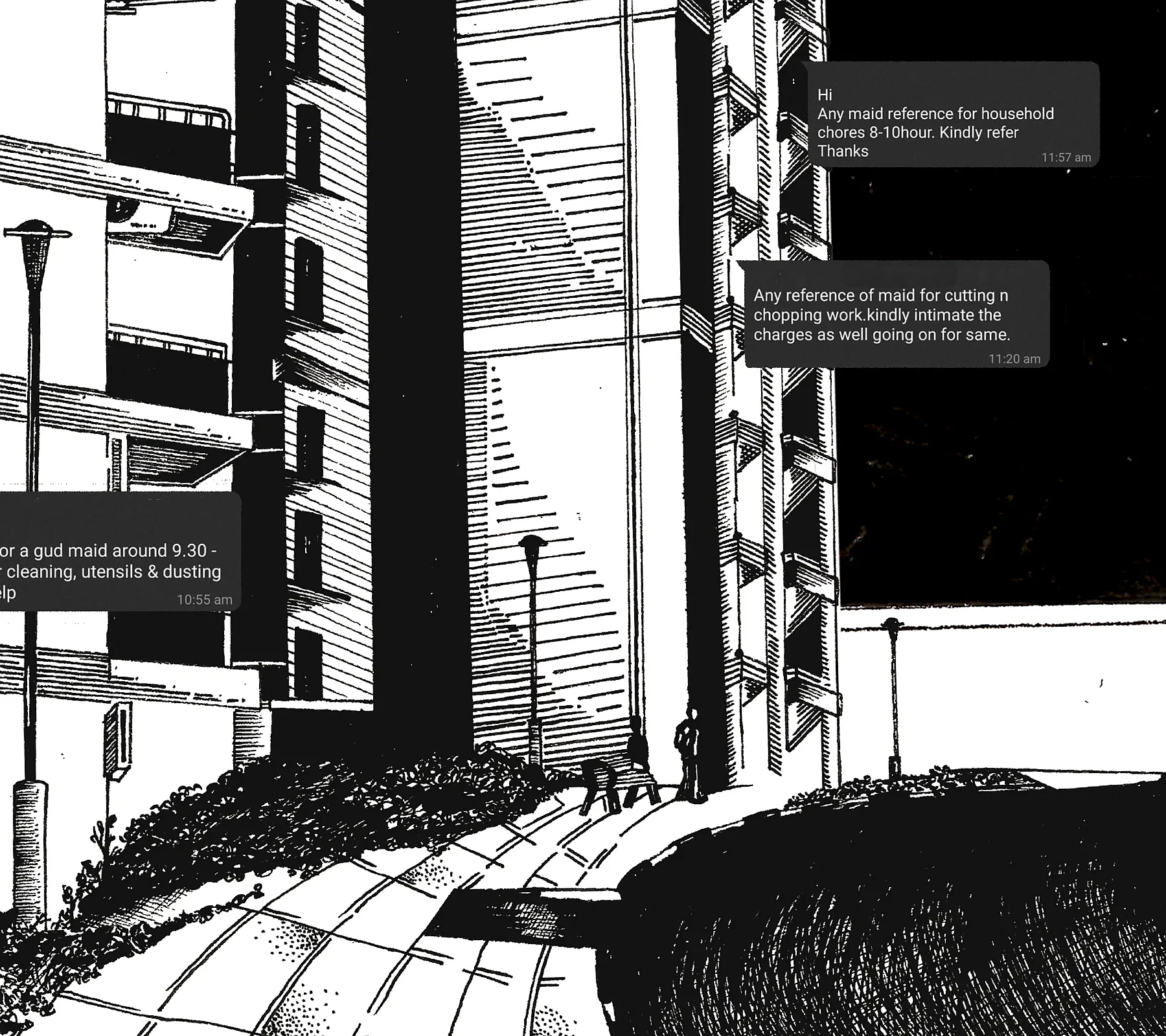

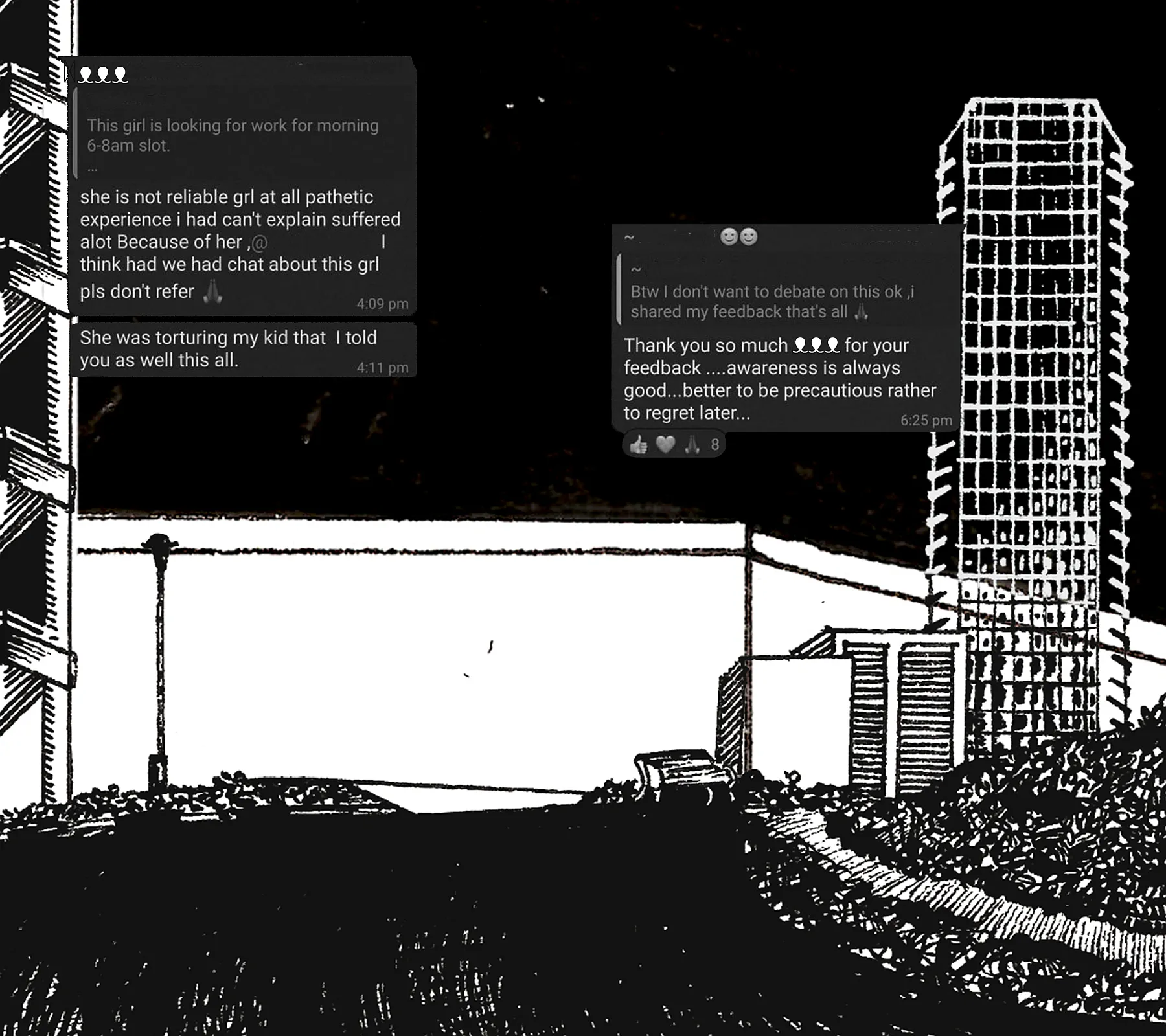

This piece is concerned primarily with workers who come into the gated complexes to work within a household unit on a daily basis, and how their spatio-temporal being is affected in various ways by the infrastructure within the larger complex. These include but aren’t limited to, segregated elevators, CCTV surveillance, resident solidarity (which is strengthened by community management apps and instant communication platforms like WhatsApp), and much more, which remains to be explored, reported on, and written about.

This piece isn’t only interested in suggesting that workers are surveilled; that much is true. It is interested in understanding extant and evolving mechanisms with which surveillance plays out, and how it affects their mobility in their workplace. It wants to explore how only certain aspects of their labour are formalised, certain parts of their labour made abstract, and how the idea of their workplace can shrink and expand as per the whims and fancies of the residents. All of this adds to the ambivalence surrounding the figure of the domestic worker, and consequently, has effects on workers and their very existence. Lastly, there are moments of camaraderie, leisure, and rest at the end of the workday, but at a cost.

Primary reporting for this piece has taken place in Noida and Gurgaon in Delhi NCR.

1 Reproductive labour is either unpaid or remunerated work that enables the ‘workforce’ to be able to go to work (such as cooking, cleaning, laundry)

2 In How Crazy Is Your Maid: Domestic Work in the New India, Sreela Sarkar writes of the “New India” as signifyings the rise of an urban middle class reliant on domestic workers. For the context of this piece ,we focus on the dynamic underscoring class and caste divides, highlighting domestic workers’ marginalisation within a modernising, consumer-driven society. Sarkar claims that it is important to understand how the figure of the domestic worker has evolved within this context of accelerated class mobility

7 This is what various domestic workers mentioned they were told as they are displaced, and this reasoning is certainly an addition to workers’ removal from lawns and public spaces on various other accounts, such as caste-based notions of purity, invisibilizing labour and upholding the complex’s sanitised vision. This does include a fundamental upper caste and class discomfort of seeing a worker at rest