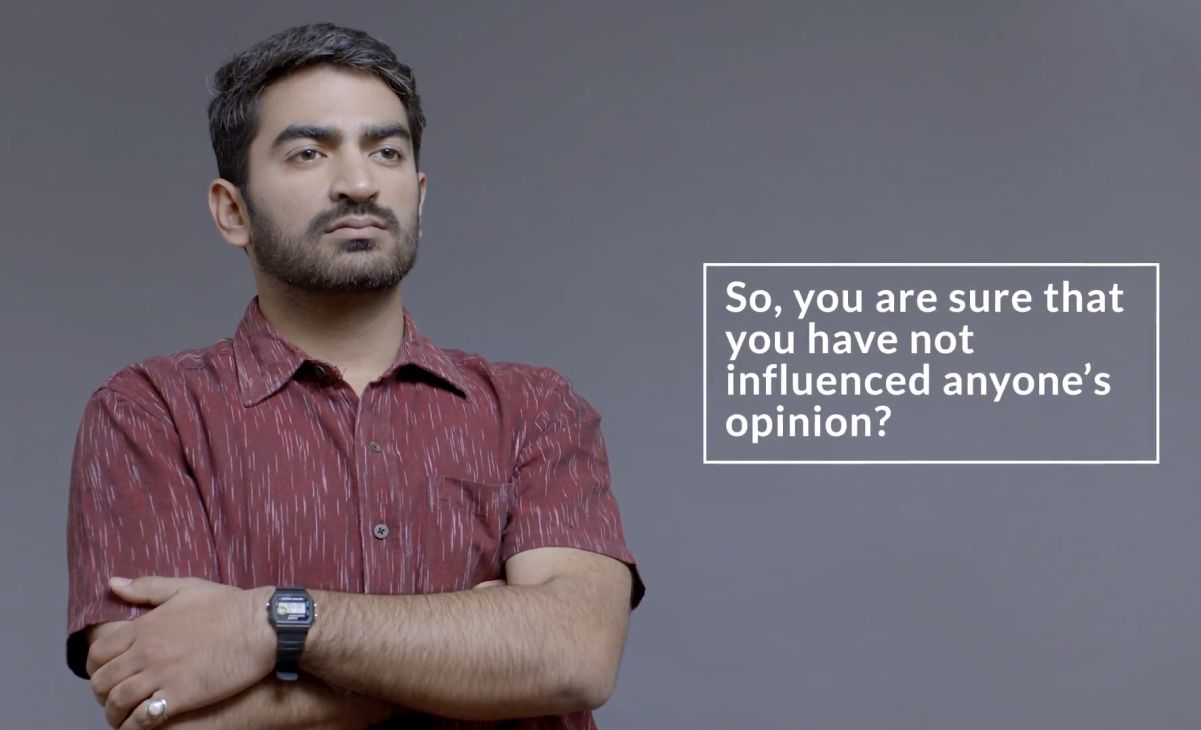

A hairstylist is bewildered that a young colleague quit and complained of harassment when as far as he was concerned he was ‘wooing’ a shy girl. A lab technician talks about her moment of shock when she realised that her jolly coworker had assumed that they were in a relationship because of their long Whatsapp chats. These are just two stories from Unboxing Consent, a set of 11 short and engrossing videos which recreate with actors, the central dilemmas of real-life cases of sexual harassment at the workplace. Delhi-based NGO Partners for Law and Development (PLD) produced this video series in 2018 to deepen conversations about consent and sexual harassment. Madhu Mehra spoke to The Third Eye about the underexplored world of feelings that live alongside the legal discussions of consent and how the video series has been deployed.

Unboxing Consent and Rejection, a video series produced by PLD and Co:Motion.

All social spaces are fraught with unequal power dynamics. But social spaces also offer avenues for kinship and intimacy. Women’s groups, anonymous Lists citing harassment by people in power, and the #MeToo movement demonstrate that harm to vulnerable human bodies and psyches is everywhere, all the time. Women and men in vulnerable positions are exploited physically or emotionally, and find it impossible to report sexual crimes committed against them. When they do come forward, they are not believed.

On the other hand, as PLD’s Madhu Mehra explains in our interview with her, not having a vocabulary to express, recognise and accept desires does harm too.

Without words, we find it difficult to acknowledge desire, define its parameters, or communicate discomfort arising from it.

This makes us vulnerable to exploitation or harm – but it also perpetuates social structures where the narratives are combative, mutually suspicious, resentful, and punitive by default.

These narratives can be even more damaging when interactions tread intersections of identities at odds with each other. Even in ordinary circumstances communication trips over differences and differentials (genders and sexualities, wealth and age, education and language, native and migrant states, caste, and varieties of privilege).

Exchanges of desire where harm most commonly occurs are nuanced and complicated; they call for exceptional self-reflexivity, empathy, and generous communication on the part of the actors. In the videos above, real-world stories unbox consent from its neat Yes/No binary to explore all the textured variations of circumstance that make it unclear to participants, and regard the visceral, psychic and social reality of rejection and the often-violent aftermath. These videos are not aimed at ‘prescription’ but they are aimed at ‘prevention’ – at fostering a deeply humane ‘consent culture’ essential to any version of social justice.

TTE: How did this project come about?

MM: Post-2013 we found ourselves being called to various places, advising organisations, putting policies in place, troubleshooting when they wanted guidance… But, we were left feeling this entire discussion embeds sexuality and sexual expression within harassment and violations. When we know educational institutions and workplaces are where people are most likely to find their sexual and intimate partners.

As a law organisation we’re not the best people to be talking about sexuality and desire, unless interfaced with the law. And if we are using these [videos] as tools to open conversations, we do want to forewarn people saying ‘hey there is law out there!’ – there are criminal and penal consequences to certain behaviours. But our total response certainly cannot be to say, ‘hey this is violation, that is violation, touching, sexually explicit language is violation.’ Because in and of itself, neither touching nor being sexually explicit are violations.

Also, in addition to the ICCs where you go to report harmful behaviour, we feel there should be more avenues to talk about it. We don’t think that the ICC folks can be therapeutic to you. They are skilled (if they’re skilled at all) to adjudicate. Subjective experiences may or may not stand the test of adjudicating scrutiny, but you nonetheless need to talk about them. Something happened, and it was painful – I may or may not want to report it. But what would make me more self-aware?

I think the videos help understand sexuality better. They’re a placeholder for the greys, and also a medium where you don’t have to expose yourselves but you can also identify that ‘oh the Pooja case happened with my boyfriend...’ It’s a safe distance, but you can be self-critical and analytical at the same time.

This is a distinctly preventive intervention. Some information, but also the way forward… Workshops can create a consent culture, to understand consent and rejection in their widest sense rather than just yes and no violation. It’s about introspecting, looking at others’ and your own behaviours critically.

TTE: So much of the scenarios that you see are a reflection of a massive breakdown in communication…

MM: But they’re also reflections of desire… Desire is not something we have that much consciousness about, a lot of the time. For example, we discount our own role in building an intimacy that turns out to be uncomfortable, or which we no longer want. The patriarchal vocabulary says you led him on and asked for it.

What we need is a feminist vocabulary to just be self aware, that says it’s okay to want, or have wanted, or no longer want, or not be wanted, or be no longer wanted - but there’s somebody else’s emotions and boundaries involved and they might not be as clear cut as yours or vice versa.

Which means we communicate as clearly as we can, but also that we accept that messes will happen. And that harm is not an appropriate response to conflicting desires.

TTE: What kinds of harm does criminalizing sex and sexualities do?

MM. One example is the POSCO Act, which makes sexual activity among under-18s criminal. So the taboo against conversation with young people about sex has been reinforced. Now, if you’re a young person you’re very likely to experiment sexually at some point. But, at no point is any information about sexuality and desire available to you; information/insight to equip you, to understand what’s happening in you life, in the realm of your psyche, in what you understand about yourself, your sexuality. You’re just being bombarded with popular culture and peer pressure. It’s important to talk to people as young as 10 about their bodies…

Because if we don’t talk about bodies, our likes and dislikes, or safe sexual behaviours, it’s utopic and unrealistic to suddenly say, when you’re 18, that no means no and yes means yes.

TTE: What kind of spaces have these videos been taken to? Has there been a demographic in mind? Have you been caught by surprise?

MM: These videos were online campaigns with Youth Ki Awaaz, Feminism in India, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter to outreach and gauge responses, what people are saying, which video is being identified with the most. Questions like, ‘How many of you thought you were not leading somebody on but they felt you were?” Or, “How does popular culture affect your understanding of love, expression, and boundaries?”

Then these videos were taken to colleges, universities, community centres – the latest one was with Breakthrough and they have been dealing with a lot of cases in colleges of Haryana of men unable to take rejection attacking women with acid. Lucknow, three cities in Gujarat, law students, students doing vocational studies like tourism, media, nutrition etc., participants in Delhi University, corporates, architecture students, engineers, the IITs etc., so the demographic has been pretty wide. They’ve also gone to community centres where we’ve reached out to people under 18.

TTE: Could you give examples, of some of the responses? What are some of the questions?

MM: One boy said, ‘I like my girlfriend so much, we were in college and we were making out and she stopped me and I thought she was stopping me because she was shy and we’d go with the flow. And I just went with the flow and she kept on stopping me, three times. Am I a harasser now, am I an assaulter? She hasn’t spoken to me since then.’ And, ‘Is it wrong to compliment women?’ Some college students, especially women, have said, ‘There are men who are our friends who we know have violated somebody’s boundaries in college – whom does the responsibility lie on, to call them out?’

There have also been instances where people have come up and said, ‘I was wronged and we were able to communicate and resolve the issue by ourselves.’

At public events in Delhi and Bombay young women were sharing that when they were younger they didn’t know it was okay to say no. If you have a self-image as a liberal and not a prude, should you be saying no at all? Women with access to the best education and to resources, fairly empowered in the way they conduct themselves otherwise, not knowing they could say no. Then the flipside: women who confess that its very hard for them to say yes.

Responses shared by queer boys, reminded us of the high standard of physical beauty in the male gay space, which makes negotiating desire fraught. Women have politicised the body much more. So, there is a feminism vocabulary to fight back. But not for the young gay men.

That is something we haven’t begun talking about. We’ve been working so hard at decriminalising homosexuality that we haven’t even got to the nuts and bolts of harassment for queer and transgendered people… so, this is an area that needs more attention.

Another thing, through these videos we have also been able to talk about gender stereotypes and sexuality. A lot of boys have said that rejection broke my personhood and my confidence totally, and I was provoked by my peer circle asking, how are you not aggressive about it? These sort of stereotypes and typecasting also lead to people breaching each other’s boundaries, assuming things about each other, etc.

TTE: The frame of rejection doesn’t get talked about very much. Can you elaborate on what conversation or context brought this idea to the fore?

MM: A lot of the cases we found were rejection cases, and we also found they were singularly lacking any feminist discussion. Rejection is so devastating to all of us because we’re not equipped to handle it in any area of life. We’re shamed for our failure… It is how much wealth you have, what clothes you wear, what language you speak – there is a sort of pass/fail everywhere. And for the ‘youth’ we’re talking about, hundreds of peers are magnifying the experience of rejection.

And we also know that certain types of people are more likely to get rejected. There is an issue of body shaming, there’s an issue of skin colour, whether you come from a small town or how fluently bilingual you are – it’s sometimes an advantage to speak English… I think it’s very volatile, how you measure who the ‘creep’ is. Who do you say no to, who do you say is creepy? Because, it is pleasurable to get a compliment or a glance from somebody who’s desirable, or whom you desire.

So, we wanted to put rejection at the centre, for what it is, because half of consent is rejection.

Workshop

Day 1

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: What is sexual harassment? What is an ICC? What is the process of reporting and investigation, what results are possible, what are the consequences? How do you handle fear and guilt? (Keep in mind: fear of reporting; guilt of reporting; guilt of rejecting in the first place).

ACTIVITY A. Divide up into pairs. Tell each other what you are most afraid of, and what you carry guilt for.

CONTEXT: Harassment happens when the person being solicited does not desire solicitation, and their lack of desire or active antipathy is disregarded. Preventing harassment requires communication. What do you want? I want this. Do you want this? Yes. May I? No. I don’t want this. Stop. This is making me uncomfortable. I don’t feel safe … The articulation of one’s desire is not a crime; it is healthy, an act of responsibility and generosity. But one must be aware of the power one wields. Are you trying to persuade a person to desire you/what you want, or pressuring them? And, are you in a relationship where the avowal of desire will be an imposition? What is the nature of your give and take? What are the types of intimacy? Who is vulnerable, and in what way?

ACTIVITY B. Screening: UNBOXING CONSENT – Raj, Mary Anne, Niranjani, Priya, Kavya, Sahil

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: What happened in each of the videos? Where did communication fail? Have you ever felt a similar failure of communication? What happened? How was it resolved?

ACTIVITY C. Divide into pairs. Tell your partner about an instance when you were either propositioned by or felt a strong connection with (or felt like propositioning) a person whose gender you have not thought of as desirable before. How did you/they respond?

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: Did you want to say yes but couldn’t? Did you want to say no, but couldn’t? Did you always know what you wanted, clearly? Did your desire ever change? Was there ever a moment you felt your wishes weren’t being acknowledged, accepted, or respected? Did you feel you were being misunderstood or being attacked/harassed? Open up these feelings and try and see where they come from (guilt/shame/peer pressure/anything else).

ACTIVITY D. Pick a video. Write a letter to the viewer of the videos, from the party not represented in the video.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: Believing the victim: Who is the victim? What does a victim look like; what does a perpetrator look like? What makes someone believable? Once again, what is sexual harassment in a he-said, she-said, and where there are at least two sides to a story? Is truth in interpersonal interactions only ever subjective?

ACTIVITY E. Divide into two groups. Group I remain seated. Group II, stand up. Everyone in Group II, ask one person from Group I to give you their seat.

Discuss how that went.

Switch roles.

Discuss.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: Kabhi haan, kabhi naa: Share a situation where you did not know what you wanted. How did you figure it out? What helped, what got in the way of figuring it out? Return to the start of the day: which relationships have you been afraid in? What did you fear? Why? How do you deal with fear? If you did not deal with it, do you regret not doing so? If you did, are you glad you did?

END OF DAY ACTIVITY: Divide into pairs. Tell the person opposite you how you feel about any one person (not them) in the room. Do not tell the person about whom your partner has revealed their feeling.

HOMEWORK ACTIVITY: Write a letter to someone you have desired but couldn’t express your desire for/to. Try and say it in a way that leaves them free and encourages them to respond honestly, and makes them feel safe.

Day 2

WARM-UP: The person you wrote a letter to last night has rejected your proposal of intimacy. How do you feel?

ACTIVITY A. Screening: HANDLING REJECTION – Ashok, Pooja, Kabir, Rajiv, and Sonal

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: Have you ever felt that a person who rejected you should feel guilty about doing so? Have you ever felt that the person who rejected you was right to do so?

ACTIVITY B: Split into groups of three. Each person shares a story of rejection (not necessarily romantic). The other two people have to troubleshoot their disappointment and pain, come up with a plan to deal with it, in ten minutes.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS:

Part 1: Has a job or admissions application, or an artwork you submitted to a competition ever been rejected? What did you do? Could you arrive at an acceptance of the rejection?

Part 2: What reasons have you rejected people (intimate partners, siblings, friends, colleagues, business partners, parents…) for? Are there any similarities between your rejection of any person and the rejections in any of the videos?

CONTEXT: Rejections are all around us. We take them in our stride. Why can we not do the same with romantic rejection? What feeling or pressure or knowledge prevents us?

ACTIVITY C. Role Play: each of you is the person you rejected. Tell everyone what happened, and how you felt.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS: When we are rejected, what makes us angry? What do we feel we are entitled to? Why do we feel it? What kinds of entitlements does society, our parents, the people we interact with, tell us (explicitly or implicitly) that we are entitled to? (The workshop facilitator should try to get participants to understand ‘entitlement’ in terms of the participant’s gender, caste, class and social positions).

ACTIVITY D. Split into five groups. Each group analyses a video together carefully. Draw up a timeline of what happened when, and where the communication broke down. Come up with an alternative for what the person facing rejection could have done to deal with it better, and an alternative for what friends and family of the rejecter/the person rejected could have done to de-escalate the situation.

ACTIVITY E. Sit in a circle. Tell everyone what the person you’d been speaking with yesterday is most afraid of. Go around the circle again. How did it feel to have your fear made public? In what context did it serve a positive purpose, and in which context did it serve a negative purpose?

ACTIVITY F.

Part 1: Split up into groups of five. Pick a video. Role play: one accused, one victim, one friend of each, one impartial mediator. Negotiate a de-escalation and a resolution.

Part 2: Same groups as before, but switch roles (and use one of the Handling Rejection videos). Accuser, victim, friends of both, and an impartial mediator. De-escalate and negotiate a resolution.

CONCLUDING ACTIVITY: Sit in a circle. Share learnings.