A 35-year-old woman from Delhi said –

“Few of my friends told me everything is shut. I did not know what the problem was, but later on I learnt from ISH news – which is a news channel for the deaf community… I was told to stay back at home, that’s it. They just said, if you got out, you would die.”

There were many like her, completely thrown off gear. In the early days of information chaos, hardly anyone remembered that people with disabilities, especially those with sensory impairments, had a right to information.

Some social analysts have termed the Covid19 pandemic as a great equaliser. Yes, equaliser it definitely is – touching the different strata of society with seemingly equal velocity. I prefer to call it an incessant gale playing havoc with the lives and lifestyles of people across the globe, but definitely not in equal measure. As always, the vulnerability of population placed at the margins of social structures was heightened. Besides the migrant workers, these marginalised sections are people from the queer and LGBT groups, persons with disabilities, and sex workers. Interestingly, persons with disabilities can be identified at the intersections of these different identities as it cuts across class, gender identities, and professions. This piece primarily revolves around the lived experiences of persons with disabilities and their families during the Covid19 pandemic.

Disability is not a homogeneous sector, or experience. Each category of impairment is characterised by a unique physical, sensory and intellectual limitation that is specific to that disability group. Even two individuals within the same disability group may have different kinds of limitations, and may require different kinds of support.

Access to Information

The announcement of a nationwide lockdown on March 24, 2020, with a four-hour window for implementation, created confusion, anxiety and panic. The situation became even more complex for persons with disabilities; for people with sensory, autism and intellectual impairments. Many people with hearing impairments felt increasingly isolated. A study conducted by Rising Flame and Sightsavers showed that women with disabilities who identified as deaf, deaf-blind and hard of hearing, faced access barriers with regard to information, communication channels, health services, to physical spaces, food and essentials, to remote/digital education etc.

People with hearing impairments who depended on lip reading for communication reported that extensive and necessary use of masks has created barriers for them in accessing of services.

People with visual impairment found it hard to access many of the apps, which were widely used and recommended to gather information about the virus like the Aarogya Setu app, since it was not screen reader friendly.

Access to information was a major impediment for those with sensory disabilities. According to a disabled people’s organisation (DPO) leader, the situation was even more fraught in the rural areas, where illiteracy compounds the effect. In March 2020, the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities had assured that all information related to COVID19 would be available in Braille and audio formats for persons with visual disability, and videos with subtitles and sign language for those with hearing disability. This was reiterated by the Ministry of Home Affairs in their guidelines for COVID19. Section 8 of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 guarantees equal protection and safety for persons with disabilities in these situations. It also mandates Disaster Management Authorities at District/State/National levels to take measures to include persons with disabilities in disaster management activities and to keep them duly informed about these. However, disability being a state subject the implementation was not even throughout the country. The incorporation of sign language in Covid19 information was done in only three states – Nagaland, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. For the rest of the country, the rights of disabled people, safeguarded under various government policies, fell through the cracks.

Social Distancing or Community Isolation

Touch and physical assistance from others is a major lifeline for many disabled people. People who are blind and deaf-blind are hugely dependent on touch for their mobility and communication.

Similarly, for people with mobility impairments and cerebral palsy physical assistance from others is almost indispensible for their survival. Social distancing is practically impossible for people with physical disabilities who are dependent on care giver support for their ADL. For others with limited mobility, support from strangers has been critical in venturing out of their homes. The spontaneous help from strangers on roads, has been greatly impacted:

“I had gone to buy some ration, and there my crutches slipped. I fell down. In normal times, someone definitely used to come to pick me up if this sort of a thing happened. But that day, no one came.”

She further added:

“Then I took out the sanitizer from my purse and gave it to the shopkeeper, and then he came to help me get up.”

People with disabilities often have to depend on support from strangers while traveling independently. With the new social distancing norms, it is likely to turn into a grey area as both lending and accepting support deviates from the protocol of social distancing.

Loneliness and isolation from friends and colleagues often resulted in depression. A man who identified himself as completely blind, partially deaf and queer said:

“Since I am not yet out to my parents with whom I live in the same apartment (and with whom I am being compelled to spend all the day within the confines of the walls). I am unable to share with them my queer distress, frustrations (sexual and emotional) and insecurities that have become manifold during the present period of global and personal crisis.”

Medicines and Medical Treatment

Some people with disabilities having medical conditions like blood disorders, multiple sclerosis (MS) and epilepsy. They found it difficult to access their necessary treatments and medications because of the lockdown. Persons with blood disorders found it difficult to access donors and transfusions, essential for their survival.

People with MS experience deterioration in their physical condition, as they were not able to receive the required therapy. As a woman in her 40s said:

“I feel fatigue and drowsy these days and also had blackouts few times… I am unable to get my main therapies – craniosacral therapy and physiotherapy – because of the lockdown.”

It was equally dangerous for people on anti-epileptic drugs. The sudden lockdown had left people without medicine stocks. During the lockdown, many pharmacies asked for recent prescriptions, which they could not get. An organisation working for persons with cerebral palsy, providing anti-epileptic drugs to students from under privileged backgrounds, had to approach the volunteers from a political party to take the initiative in distributing medicines in different localities and slums of Kolkata.

Food and Essentials

The lockdown saw a rise in food crisis across the country. Persons with disabilities were one of the worse affected groups. The crisis was witnessed both in urban and rural areas. This was despite the disability inclusive mandate given by the Central Government and Department of Persons with Disabilities under Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment: Persons with disabilities should be given access to essential food, water, medicine, and, to the extent possible, such items should be delivered at their residence or place where they have been quarantined.

The reality that surfaced was different. Mathivannan, a person with disabilities in Chennai was struggling to find food for 10 days.

“From the Amma Unavagam to NGOs stepping in with cooked food and supplies — I tried all possible options. Some organisations told me that there weren’t enough provisions to be spared for us. We are 150 people with various forms of disabilities in Kannagi Nagar.”

Online deliveries are not always a viable option for persons with disabilities. The online apps are mostly not compatible with the screen readers widely used for persons with visual impairment. Moreover, for people with physical disabilities carrying the goods back to their homes proved to be a difficult task. A 54-year-old disabled woman from Ghaziabad narrated:

“The online store people have dropped the groceries at my society gate. I am not able to pick up the 5 kgs and request them to carry this product. They refuse … I am forced to pick that grocery up from the gate to my home and then the whole night I spend in pain.”

Social Protection

In early April, the central government announced various measures like three months of advance pensions under the Indira Gandhi National Disability Scheme under the National Social Assistance Program to persons with disabilities, and announced an additional support of Rs. 1000 to be paid over a period of three months in two instalments. Despite central guidelines and commitments, many social protection and relief measures particularly those outlined in the disability inclusive guidelines still remain a distant reality for persons with disabilities and more so for women with disabilities.

There were mixed experiences of persons with disabilities throughout the country in availing these schemes. The study by Rising Flame and Sightsavers found that there was state wise disparity in pension disbursement. The finding shows that:

Assam: In April, the participant, a 30-year-old woman, received the advance pension (Rs. 1000 per month). She had not received the pension for the month of May.

Rajasthan: Pensions were very erratic in general. A woman with locomotor disability from Bikaner informed that every April, eligible persons with disabilities were required to provide proof of their being alive to the authorities, which could not happen because of the lockdown and lack of transportation. Hence pensions were suspended till then.

Bihar: Participants reported having to go to the bank to access the cash transfers. A 37-year-old participant with locomotor disability said that because of the closure of public transport her only option was to walk 3 kilometres to the bank, which is why she could not access the amount.

Education

The lockdown per say ushered with it the concept of online classes. Suddenly, both teachers as students found themselves trying to adjust to the virtual methods of teaching and learning. However, for persons with certain types of impairments these digital platforms are inaccessible. Students with hearing Impairments found themselves with no sign language interpreters. As a student of Delhi University recounted:

“During the session most people, including the teacher, prefer to keep their videos turned off limiting the scope for lip reading. I have no option but to miss out the discussions. I have to later ask my classmates for an update.”

The online classes are equally inaccessible to the visually impaired as most of these platforms are not compatible with the screen readers. Moreover, most of the assignments are scanned in PDF formats which mean that the person has to take help from someone to read out them.

In the midst of such gloom, a positive note was shared by a mother of a 13-year-old boy with autism:

“When the lockdown was announced, the first thought that came to me was how my 13-year-old son with autism would react…. Individuals with autism don’t like change, I had heard from many. Their love for routine and ritual is common knowledge for all the mothers like me.

It was then that the special educators of my son’s school, Dikshan, a unit of Autism Society West Bengal (ASWB) reached out to all the parents. Almost overnight, the teachers prepared social stories on the Coronavirus and its spread; meaning of lockdown; safety protocol to follow at home. These social stories were circulated via WhatsApp. Videos and voice messages were used to explain the lockdown and its probable implications. They guided us on how to make new personal schedules for the students, to help them get used to the change…”

Covid19 and Violence

The Political Angle

A Personal Perspective

As for others, the lockdown came as a sudden jolt that literally threw by life off gear. While I wrote this article, I could relate to many of the narratives as a mirror of my life. The journey through the last few months has been a roller-coaster ride. Economic uncertainties and the panic of being alienated from my familiar territory of work, travels and social life, I went into an emotional rigmarole. Fortunately for me, there were people to handhold me through this high tide of crisis. I wrote a few lines to unburden my nightmares and they said,

The flood water bubbled

Stealthily raising inch by inch

Camouflaging its existence

Creeping quietly to engulf the human kin

Acknowledgement:

My sincere thanks to those persons with disabilities, parents and professionals who shared their experiences.

References:

Rising Flame & Sightsavers:

Neglected & Forgotten: Women with Disabilities during the Covid crisis in India

Persons with disabilities bear the brunt of coronavirus lockdown

https://thefederal.com/states/south/tamil-nadu/persons-with-disabilities-bear-the-brunt-of-coronavirus-lockdown/

A heart of gold, iron grit: Marginalized turns saviours during lockdown

https://thefederal.com/features/a-heart-of-gold-and-iron-grit-marginalised-turn-saviours-during-lockdown/

Ghosh N: Factoring disabilities

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/open-page/factoring-in-disabilities/article31710301.ece

Jeeja Ghosh was born with cerebral palsy, a condition caused by lack of oxygen to the brain either during pregnancy or at the time of delivery. She completed her schooling from the Indian Institute of Cerebral palsy and La Martiniere for Girls, Calcutta. She graduated with Honours in Sociology from Presidency College. She is a qualified social worker (MSW) from the Delhi School of Social work, Delhi University. In 2006, she completed her second masters in Disability Studies from Leeds University, UK.

Jeeja has been involved in the social sector for more than two decades. She has been a part of the disabled people’s movement, with a special interest in women with disabilities. Jeeja worked as the Head of Advocacy and Disability Studies at the Indian Institute of Cerebral Palsy in Kolkata till October 2018. At present she is an independent consultant on gender and disability primarily in the area of training and research.

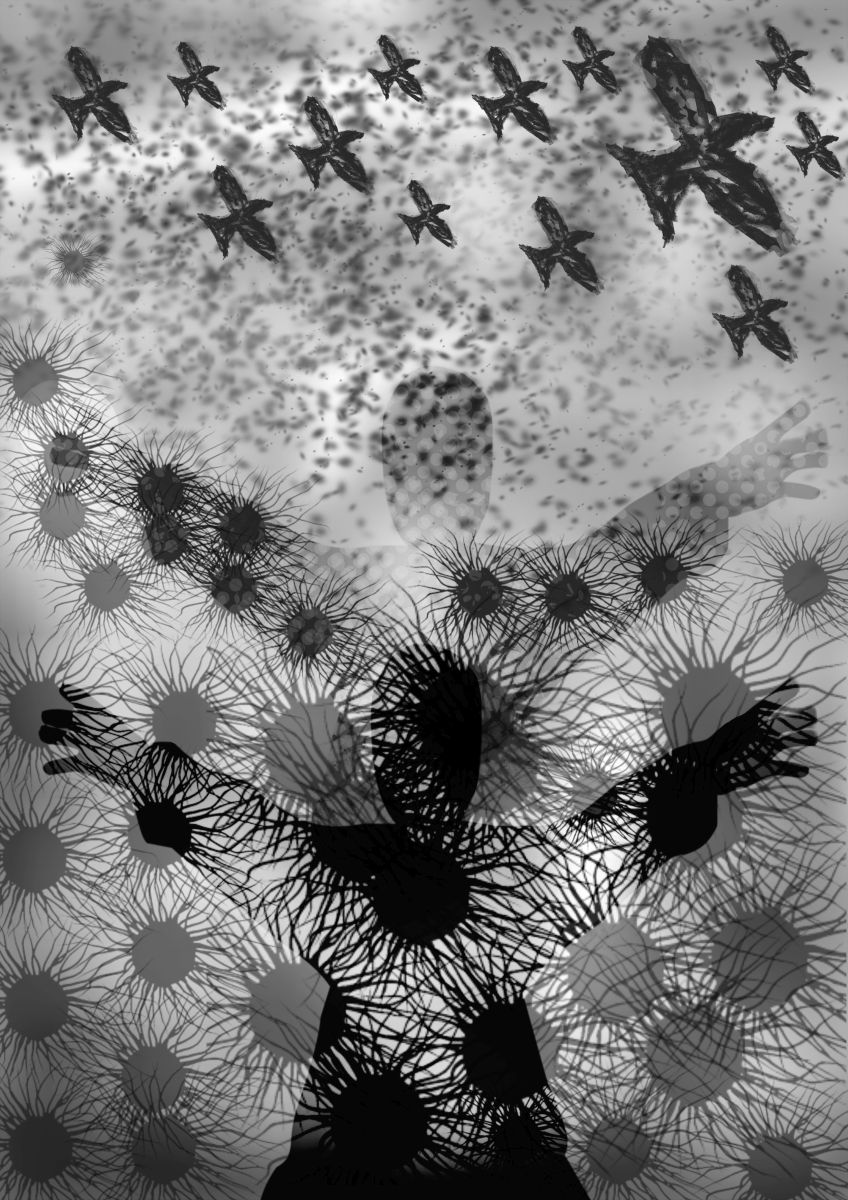

Mandeep Singh Manu was born in Amritsar in 1981 and was diagnosed with cerebral palsy as a young child. His practice is focused on exploring concepts and meditations in the form of digital prints. He graduated from the Indira Gandhi Open University and has a post-graduate degree from the Punjab Technical University.

He has participated in numerous international exhibitions in over 15 countries, including Biennial and Triennale exhibitions in Poland, Lithuania, Iran and Brazil. His work is the subject of three current Ph.ds.