With inputs by Astha Bamba

As we worked on the Crime edition, we came across the term ‘carcerality’ many times. Feminists and social justice advocates have written extensively about the continuum between the most surveilled spaces – like prisons – and everyday life.

We wondered about this; are our lives governed by principles of carcerality, the most common being confinement, surveillance, and punishment? And what role does public space violence play in building a carceral logic into our lives?

In her paper, ‘Carceral Cultures in Contemporary India’, researcher and editor Mahuya Bandhopadhyay, describes what she calls a ‘carceral spillover’:

The deadly aspect of hardwiring violence beyond prison walls is that you no longer need prisons or custodial settings like a lock-up or torture cell to employ violence as a technique of containment of the undesired and the aberrant. It can now be done on the streets—used as a metaphor for ‘free spaces’, spaces where citizens may feel free to express themselves. The use of violence in these free spaces is what I call carceral spillover for a certain set of people, and the definition of who belongs to that group is expanding.

Do we find a carceral spillover in the spaces we live, study, work and seek care? What are some of these ‘free spaces’ and who are they free for? To make sense of this spillover, we draw from writings, films, letters, and music to curate a list of these everyday spaces around us, where we perhaps see carcerality quietly – but forcefully – inform every cell of our being.

1

Residential societies

Feminist studies have examined surveillance and control within the structure of the home and the family. But how does it extend to spaces beyond the walls of the home, especially in the rising urban residential colonies where the ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ become deeply politicised? Within the gates of these colonies, an exclusive semi-public space gets defined, which is often a site of control based on caste, class and gender, mirroring the policing inside the family unit and projecting it onto the broader community.

In her report, I took Allah’s name and stepped out: Bodies, Data and Embodied Experiences of Surveillance and Control During COVID-19 in India, researcher Radhika Radhakrishnan looks at the nature of surveillance by the RWA’s (Resident Welfare Associations), a civic body that often manages these spaces:

“The data collected through CCTVs is accessible only to RWA officers and heads, and is used to surveil ‘outsiders’. The presence of cameras outside society gates is a way to signal who belongs in a particular space and who should be kept out of it. In the context of the stigma around marginalised bodies during the pandemic, the cost of such surveillance is mostly borne by communities, such as those of domestic workers, who are already being denied entry into these spaces.”

2

Psychiatry Clinics

In her book The Occupied Clinic, Saiba Verma closely examines the space of a psychiatric ward in Kashmir. In the opening paragraph, she writes her observations of this space, drawing parallels between medical care and a carceral space:

Life here moves more cautiously than in the OPD. Some are here because their level of distress warrants long-term hospitalization; others have stabilized but cannot return home because their families feel ill-equipped to care for them or, in some cases, have abandoned them. I have been spending my afternoons in the women’s closed ward, trying to develop a rapport with the dozen or so patients and the two “wardens,” Asmaji and Haleemaji, in charge of them. Despite the hospital’s commitment to outpatient, community-based mental health care, its past as an asylum still lingers. Prisoners and wardens, not patients and caregivers inhabit wards that feel more carceral than caring.

Every day, we carousel through the same routine. Lunch at 11 a.m. It is one of only two times each day that patients are allowed out of the ward. Sometimes, if the weather is nice, the wardens will let them sit on the grassy knoll outside and soak in the sun for a few minutes, a small relief from the dank inside, where the sour smell of cheap disinfectant and mothballed blankets hangs in the air. By 12:05, everyone is back in their beds, awaiting their medications. Counsellors sometimes lead recreational activities for the patients, but these happen erratically. Days fold into each other, only occasional creases marking time’s passing.

– Extract from The Occupied Clinic by Saiba Verma

3

Digital

In his seminal work Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault analyzes the panopticon, an architectural prison design proposed by social theorist Jeremy Bentham, where a guard in a central tower observes all the surrounding prisoner cells. The power of the panopticon lies in its one-way surveillance—where the observer in the tower sees everything, but is never seen, and the inmates remain constantly aware that they are being watched.

In the digital age, ‘being watched’ is a reality that we perhaps knowingly live with. Yet, as we also constantly do the ‘watching’, could it be said that each of us also inhabit the central tower, with a virtual panopticon circle orbiting around us at all times– one that sees us as much as we see them?

In the film LSD 2, Dibakar Banerjee explores this complex two-way relationship of watching and being watched. Through its three stories set in different, yet intertwined digital worlds— a live streamed reality TV show, a cacophony of zoom meetings, a small Youtube channel and video calls, and lastly a fully virtual life of a teenage gaming streamer— the film constantly questions our symbiotic relationship with the digital eye. The eye that gives us freedom to express our ‘I’, connect, and produce, also constantly watches and surveils us, which, thus, shapes our ‘I’.

Speaking about the film, Dibakar refers to this virtual carcerality:

“The internet gives us a certain kind of independence. In the virtual world, we can be whoever we fantasize to be…but when we reinvent our identity and try to sell it, we are caught in it and that’s the exact opposite of freedom.”

Applying the Panopticon theory to the digital context in India, the CPA Project’s report titled Building Blocks of a Digital Caste Panopticon: Everyday Brahminical Policing in India defines a Digital Caste Panopticon:

Casteist digital datafication of marginalized bodies—in this case those from oppressed caste groups—has been a crucial part of the creation and entrenchment of this surveillance project.

Drawing on the philosopher Michel Foucault’s analysis of modern disciplinary societies, combined with his later conceptualization of power in the form of governmentality, our contention revolves around the disconcerting trend where tools like surveys, when combined with unbridled policing technologies, set in motion what we call the digital caste panopticon.

With the case of Telangana, we argue that growing digitization of policing solidifies the confluence of colonialism and caste. We use the term “Brahminical policing” to refer to a violently imposed ideology that positions Brahmins as the epitome of purity in the hierarchy of caste, and that includes within it the eugenic tenets of colonialism. This form of policing extends its reach well beyond ostensibly public spaces, into the everyday lives of marginalized communities.”

4

Hostels

Reinforcing the age-old sentiment that ‘a woman’s place is in the home’, hostel spaces are common sites of control and surveillance. In this hostel space, which is linked to the structural and authoritative body of the university or college, this control takes a more formal and confident form. Strict regulations and curfews are imposed, and almost exclusively targeted at women students.

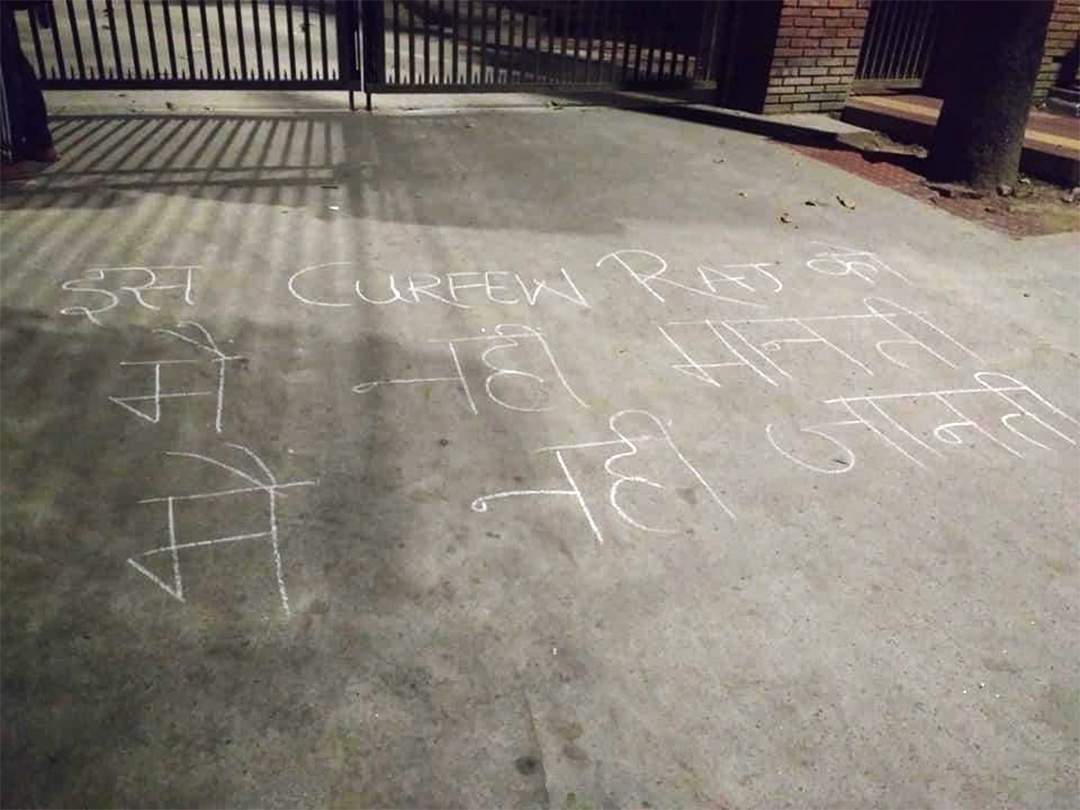

In an open letter by students of Jamia Milia Islamia, addressed to the university’s vice chancellor, women hostellers have voiced out their frustrations regarding the gendered restrictions imposed on them:

“A university is meant to be an inclusive space harbouring an environment that fosters growth. However, the differential access we have to the University and the city itself restricts us from being able to fully exercise our autonomy and experience the city space unlike our male brethren. The rules in the hostel often force us to question whether we are students or inmates in a prison, constantly being policed and questioned about our movements. For instance, the hostel rules mandate that for women students there be a roll call every day to check that every resident is present. No such process exists for the men. The fact that we have to take ‘permission’ from our local guardians if we wish to go out of the hostel robs us of any sense of agency and dignity. It is reminiscent of the era where women were relegated to the realm of the household and considered nothing more important than a decorated mantelpiece.”

5

Coaching / Kota factory

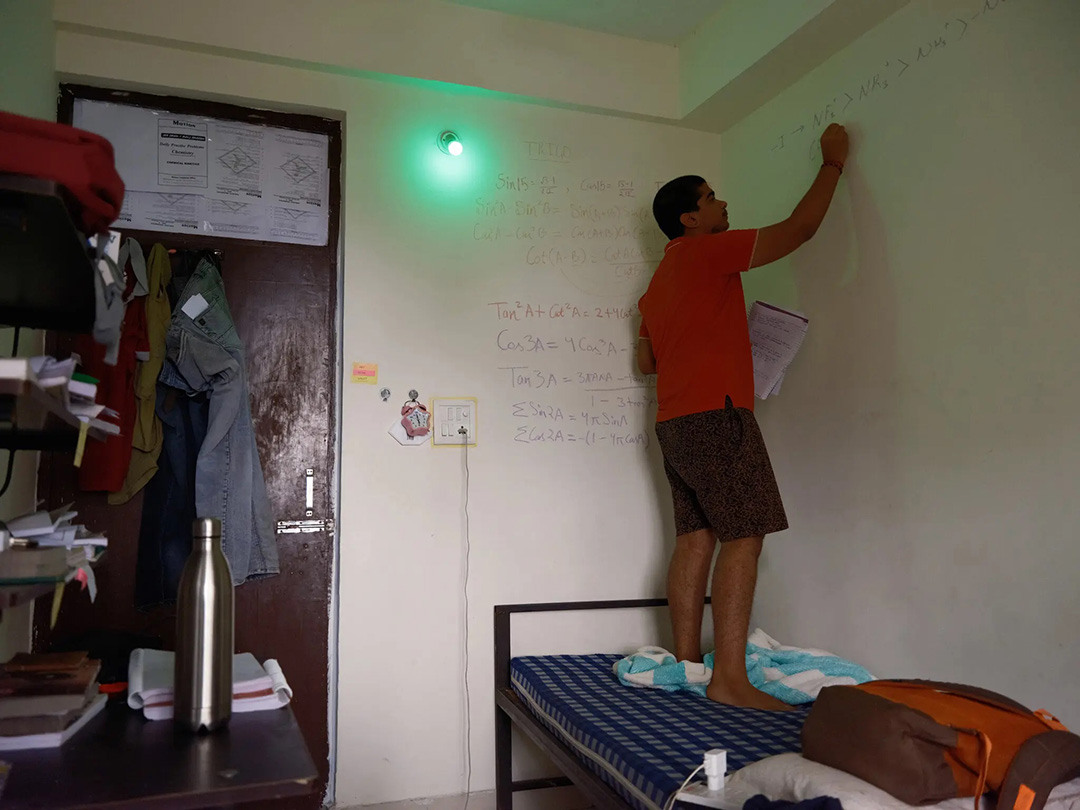

In the New york piece ‘Cram City’, written by Mansi Choksi and photographed by Zishaan A Latif, Choksi writes in observation of the students in Kota’s coaching centers, who arrive from distant locations to prepare for the highly competitive IIT-JEE and NEET exams.

“The never-ending hours of study, the missed birthdays and family gatherings, the sting of disappointment, the loss of friends, hobbies, fresh air and the experience of being young — all of it combines to turn Kota into a pressure cooker. Friendships are tainted by the fear of getting attached to a competitor. Watching a movie means throwing away your future. In the end, the merciless culture of competition can push students over the edge.”

In the series of photographs by Zishaan, we see walls scribbled on by students – from formulas in their dorm rooms to prayers and wishes that fill the temple walls of Kota. Govind (in image above), says in the piece, “Surrounding myself with the material means I am manifesting results.” Each corner of their everyday environment, from alarm clocks tucked under pillows to these scribbled walls, feel like silent echoes of who they hope to be when they get out of the tight structural confines of the cram city.

6

Labour site

In Megha Acharya’s documentary film Meelon Dur (Miles Away), we observe the everyday lives and routines of three women working as migrant labourers in a brick kiln in Bundelkhand. Their work embodies a Sisyphean repetition, as they aim to make as many bricks as possible each day, earning Rs 600 for every 1,000 bricks. In the opening sequence of the film, Ramsakhi, one of the migrant workers:

‘Every year, we decide not to return to the brick kilns. But after going back home, we don’t find work. We take a loan from the kiln owner. Spend some of it on ourselves, give some to our son. Then we work here to clear the debt. We also take weekly loans…of Rs 1,500 to Rs 3,000 for groceries. We repay this along with the debt we took before coming.’

The debt binds them to the space, as they return each season to the kiln with their families for work. In another sequence of the film, we see the women playing Holi with each other, where one of them remarks, ‘Here, at the kiln, there are many women…so we’re able to play Holi. Back at our in-laws’ home, whom do we play Holi with?’

Here, carcerality is not limited to the kiln, as women often have to navigate it in various aspects of their everyday lives. While the kiln does impose a form of control, it atleast offers them friendships, which are often lacking in their marital homes. There are nuances in their relationship with this space, as carcerality takes on a more fluid form, shaping how they navigate their freedom, and often having to choose between one kind of carcerality over another.

7

Schools

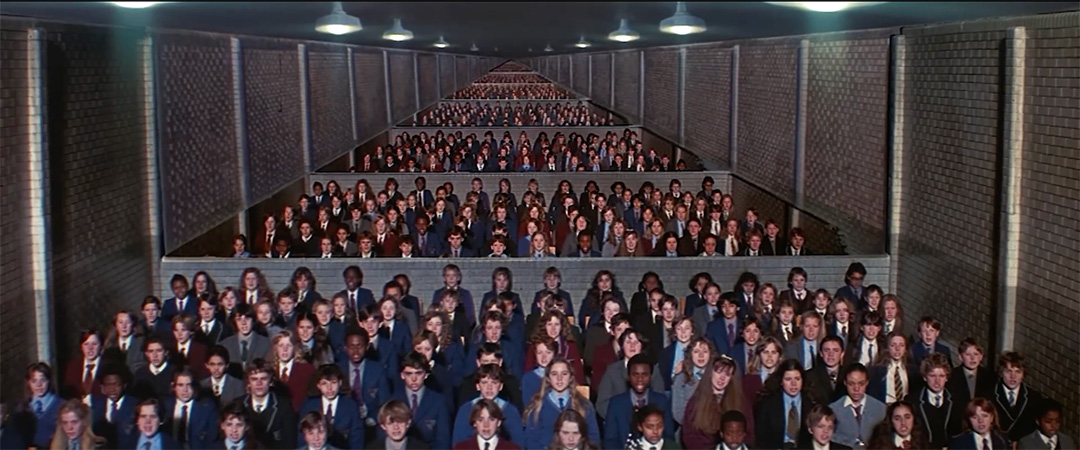

In the music video of the popular classic, ‘Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)’ by Pink Floyd, school children walk like zombies in a factory-like space. Their movements and routines resemble an assembly line setup, as they walk in unison, wear the same masked expression and chant in synchronised rhythms. But they also create fissures into this routine, as they chant, ‘We don’t need no education’. Band member and songwriter Roger Waters says that he intended to question the British education system, but rather than just critique, he wanted one to imagine an alternative:

“Obviously, I care deeply about education. I just wanted to encourage anyone who marches to a different drum to push back against those who try to control their minds rather than to retreat behind emotional walls.”

Released in the late ’70s, the song remains a timeless classic. Even today, when one opens the music video on YouTube and scrolls through the comments, many echo a similar sentiment: “Doesn’t it feel more relevant now than ever?”