Every 12 minutes, a young addict walks into the OPD in Kashmir, stated an Indian Express front page report, dated August 18, 2023.

In Kashmir, ‘young’ and ‘addiction’ have become synonymous. Now, a band of youngsters enjoying their youthful time around a lake is seen with intense suspicion and concern rather than amusement and well, nostalgia. (Jawaen chu jawaanihun lutf tulaan, as they say in Kashmir).

What are the lives of these young people like? What do they experience around addiction, and how does it influence their imagination? What makes them come to the OPD? While their lives are complex (and sometimes too intense to be processed), is there a way to talk about their reality? And what can we learn about systemic crime from their lives?

But the story we know places men at the centre of the struggle. Apart from a few other reports, there’s hardly any conversation on how addiction shapes and is shaped by a Kashmiri woman’s experiences.

In this fictional re-telling inspired by personal conversations, desk research and reported stories, I deconstruct the experiences of a young Kashmiri woman’s journey and motivations into addiction by compressing her life into those ‘12 minutes’. What happens within those 12 minutes, for her to reach that OPD?

“I’m going out now.”

Seerat closed the door behind her, humming to drown out her mother’s entreaties to hurry back home. It was an hour-long ride to the hospital, with a bus change in between. Her face was covered with a thick, black scarf, and her black salwar kameez hung loosely over her gaunt body.

She and her mother lived on the outskirts of the capital, Srinagar. Her mother sewed clothes for a living. Seerat, in her mid-twenties, helped her mother in her tailoring business, but was dissatisfied with the direction of her life.

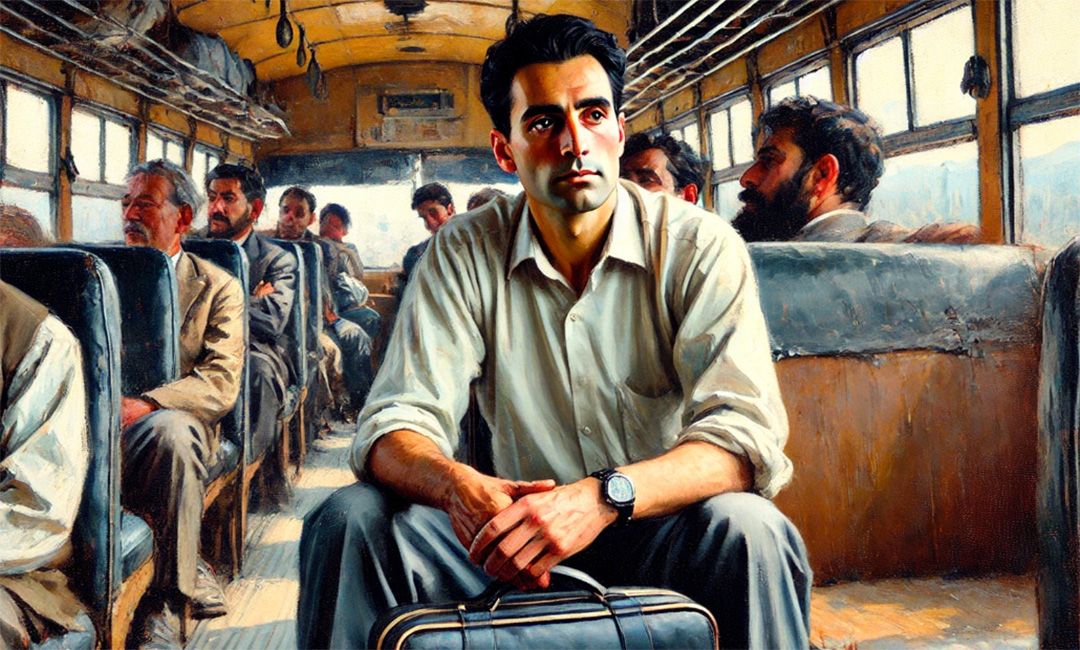

She walked to the bus stop on the main road, checking her phone’s clock. It was noon. She looked up at the sky – it was a cloudy day today, but hotter than usual. A few people glanced her way, eyeing the thick, woollen scarf out of curiosity. The bus shortly arrived and she squeezed into the crowd, finding a standing spot behind the driver’s seat.

Minute 12: Overdose to Minute 1: Childhood [How do you treat someone?]

Seerat never liked buses as a child. She disliked the conductors’ loud voices, the spraying of spit whenever they called out the bus’s destination; the constant need to add more passengers to the bus’s already burgeoning capacity, and the strangers touching her. Until she was old enough to feel embarrassed, Seerat clung to her mother’s lap whenever they found a seat, and screamed out loud whenever a stranger’s hand approached her body.

Her mother would laugh it away and explain her ‘sensitive’ temperament to surprised passengers. Once at home, her mother would hit her with soi, a nettle leaf found easily in gardens in Kashmir. The contact of the nettle leaves with Seerat’s chest and back would leave a stinging sensation. Wiping Seerat’s tears and putting her clothes on, her mother would say, “Stop embarrassing me. You’re old enough to know better.”

The red stings lasted for an entire night, and Seerat would writhe in pain. She would think her mother was a monster, and cry herself to sleep. Why was it wrong for her to feel uncomfortable from an uninvited touch? The next morning, her mother would go out early to buy harissa, a meat stew that Seerat loved. Once the smell of the stew would cross the kitchen and into the hall, Seerat’s heart would forgive her mother, and her mind would convince her that yes, it was Seerat herself who was to blame.

Ten years later, when Seerat smoked weed for the first time, she felt the stings of her mother’s beloved soi all over her back. Sitting behind an abandoned building near her school, vivid images of her mother’s smiling-then-angry face floated in her head. Seerat lightly touched her fingertips and smiled back at the images in her head. At least she remembered her mother’s beauty.

Minute 11: Desperation to Minute 2: Adolescence [How do you locate crime in treatment?]

The bus jolted forward, and Seerat’s head hit against the partition door. A passenger behind her, a man in his mid-40s, let out a gasp and asked her if she was okay. Seerat touched her head, protected by her thick scarf, and nodded. Her gaze rested on this man for some time.

His eyes were alert, yet tired. He was wearing a shirt, and formal pants, and looking outside the window. He was clean-shaven, with his hands folded. Truth be told, he didn’t match the bus’s rickety vibe at all. His black briefcase stood on the ground, between his polished shoes. Seerat searched his face for any signs of familiarity.

Seerat didn’t know much about her father, and her mother was tight-lipped about him. She only had a handful of memories of him — one in which he and her mother were quietly sipping tea after the morning prayers, and another in which the family went to see the Tulip gardens, because her father insisted on it. In the memories, her mother was kinder and smiled more. Sometimes, when she daydreamed, she could mentally draw out the warm crinkles around her father’s eyes.

After a point in her childhood, her father stopped existing. Seerat heard murmurings from her mother’s brother; he was picked up by someone in the middle of the night, and never seen again.

She’d wanted to ask her what ‘picked up’ meant, but with time and the virtue of living in Kashmir, the answer came to her.

Shortly after her father’s disappearance, her mother’s brother insisted they move to another area. He built a small house for them. While she loved her maamu, Seerat sometimes felt afraid that her father had no way of knowing they moved, and would’ve come back, expecting them to be there, and not find them.

Yet, Seerat never dared to go back to the area they once lived in. Except that one time, a year ago, when she had asked the drug peddler to meet her in front of her old house. Some part of her was feeling malicious towards her father who had left her and her mother to rot in this world. Perhaps he was lurking somewhere, in the house or nearby — perhaps he made it a routine to come at a specific time every day, hoping to catch a glimpse of his now adult daughter. Perhaps his eyes widened in shock upon seeing her gaunt figure, and he felt guilty for abandoning her.

“Why did you choose this location?” the peddler said. “Don’t you know it’s famous for disappearances? Are you trying to get us both killed? You should learn to think like a criminal sometimes.”

Seerat said nothing and gave him a few thousand rupees of cash, stolen from her mother’s purse. She was already a criminal in her mother’s eyes.

On the bus, Seerat checked the time. It was quarter past twelve.

Minute 10: Abyss to Minute 3: Abysmal [What is the reward of a drug?]

In school, Seerat didn’t stand out much. Her maamu had sold a piece of land to aid her financially. Her maamu and mother had grown closer after her father’s disappearance, and she knew her mother wanted Seerat to feel the same way about him. Her maamu was kind and supportive. He defended Seerat’s right to education and often tried to help her in her studies.

But Seerat felt burdened. Each time she saw his face in the house, she was reminded of how much of her life was in his hands. She felt irked when he acted like a father, buying gifts for her birthday and Eid, and suggesting the three of them go to Tulip Gardens again.

When maamu got married, things got easier, but her mother’s mood worsened. Maamu now had new responsibilities towards his wife and incoming children, so he didn’t visit the house much. He sent money for expenses and came with his new wife a few times, but he couldn’t be as involved anymore. Seerat felt her mother’s envy and anger over her own life.

One night, after school, when they both sat down to have dinner, her mother swallowed a pill. The pill was white – it looked harmless and innocent. Seerat wanted to ask what it was, but feared that the nettle plant would be sacrificed to deal with her mother’s rage.

As Seerat got older, the empty sachets of the pill increased, and the prescriptions got longer. Her mother’s vocabulary changed — from words like ‘stress’, ‘sadness’, ‘hurt’, she progressed to use words like waenij raavyen (anxiety), doud wan (depression) and ‘trauma’. Seerat thought the pills helped, but was worried about the frequency and speed with which the sachets were emptying. It didn’t help that every six months or so, the size of the pills got bigger. She became a silent witness to her mother’s friendship with the pills and the loneliness and frustration that followed her like djinns.

In many ways, she could relate to her mother. In school, she usually kept to herself or was the afterthought added to a group that was sympathetic to her. She had heard bits and pieces of what people talked about her. Some thought she had a loose screw, some blamed her father’s disappearance for her solemn expression. Others felt she was just strange — so strange that it was okay to hurt her. Teenagers were mean, and once they found something that amplified their meanness, they would tend to repeat it. There was one phrase boys would often tell her:

“With a face like that, no wonder your parents named you Seerat [inner beauty].”

Sometimes — especially on days when she was menstruating — Seerat would steal some time away from class and visit one of the half-constructed buildings behind the school. The buildings were intended for student sports facilities, but funding fell through halfway. Since then, graffiti, dog and cat poop, and cigarette butts lined the walls of the building. Seerat didn’t mind the smell of poop — animals were kinder by default and knew how to co-exist naturally.

She was happy no one had found this hideaway, or wasn’t interested enough to stay. It felt like the one place that was hers.

One morning, after a bad nightmare, she decided to visit the hideaway right before class. She found the source of the cigarette butts. A young boy, from another class, looked up to her in surprise, and then amusement.

“Do you smoke?” he asked. Seerat shook her head and stood rigidly. But the boy stayed until he finished his cigarette and threw the butt on the ground.

“Don’t tell anyone I come here,” he said. “Or I’ll beat you to pulp.”

She nodded, clamping her mouth so that the strong smell wouldn’t make her cough. He got up and grinned. “You should also try smoking next time with me. It’s fun.”

She said nothing and waited for him to leave. After his footsteps faded, she coughed loudly, spitting at the spot he had sat.

She would never smoke.

Minute 9: Experimentation to Minute 4: Love [What is the punishment?]

The man with the briefcase stood up in the bus and Seerat took his seat. Her legs sighed in relief and her gaze went to her watch. Half past twelve. She watched the houses rise over the hills, the dilapidated roads ribbon across, and the occasional loud biker whizz past. Life was slow here, abominably slow.

She often thought back to the first time she had held a joint. It was an innocent-looking, thin stick that could be easily squashed into two. She didn’t like the smell, but she liked how it would make her forget the heaviness in her head.

The boy, Sahil, was around her age, and from a different class. He had an eccentric, underdog charm around him– he could make even the strictest teacher laugh, and he knew how to turn the school’s rules in his favour. He was intelligent if he put his mind to it.

Most of all, he was honest. About everything in his life. When she told him she wanted to try a puff, he gave her an unreadable look. Then he sat her down near the building and told her, “We’re humans. We believe in transactional relationships. Look at the relationship with your mom. Do you think she would love you if you didn’t study if you didn’t pray?”

“You and I have to follow these rules. So if you get drugs, you get happy. But I already have drugs. So, what do I get from you that makes me happy?”

After that, Seerat remembered how his gaze travelled down her stomach, and his hands touched her shoulders. She immediately shut her eyes and stayed still. Very, very still. Just like the thin joint stick that would make her happy. Later on, Seerat would hate the burning sensations near her thighs and try to block out his laboured breaths near her ear.

There were times when she didn’t hate him. Like the time when, while being high, he told her about his little sister who had died during an encounter. She had been crossing the street, returning from her usual Islamic Studies classes, when she was caught in the crossfire. It happened in a blink of an eye. Seerat saw his eyes tear up and his voice crack.

“Do you ever feel helpless?” he said, as he inhaled another puff from the joint and passed it to her. “Do you feel it’s wrong to feel so good when you’re supposed to feel helpless?”

“I think we’re used to hurting each other too much,” Seerat said, remembering her mother, “and we cannot imagine treating each other differently.”

After some silence, he said, “I feel nice here with you,” and took her hand. “It’s like you know my whole heart, even the dark pieces of it.”

Seerat felt herself blush for the first time. “Me too.”

Neither of them knew how to act, but both were used to figuring it out by themselves. And so, they began a mutual relationship based on attraction and criminalised behaviour.

****

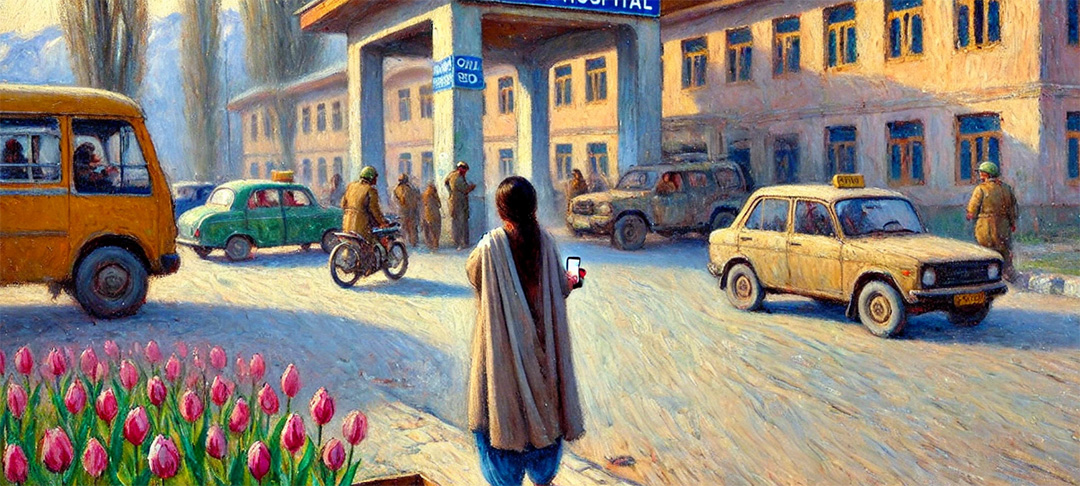

The bus stopped and the conductor screamed the destination name. Seerat alighted with a few others into the bus terminal. She crossed the street to reach the next bus stop. From there, it would be a half-hour journey to the hospital.

She hadn’t told her mother she was going there. She had a penchant for lying. But her mother had grown suspicious of Seerat over the years and regularly asked maamu to monitor her actions. More than a few times, maamu had come unannounced to her school to check on her.

“I won’t tell your mother,” he would say, when she came to his car outside the school gate to see him off. “So, fix yourself and maintain your dignity. Your mother too is not right in the head, but it’s not her fault. You have to be strong. Do you understand?”

Seerat nodded, only so his mouth would stop moving.

In those days, Saahil helped her by keeping a lookout and being a friend. She was grateful for him because he understood.

But as time passed, she began to grow weary of Saahil. He was always searching for the “rush” — the adrenaline that could fill the boredom and helplessness he felt in his life. At first, getting physical with Seerat helped. But he wasn’t satisfied.

One day, Seerat saw him passed out in front of their hideaway. Besides him, there was a small foil with white powder. She immediately felt something was different. She bent down to hear his chest. His heartbeat was erratic, but he seemed like he was sleeping. She put a bottle of water next to him and decided to come back later.

A few hours later, he woke up and left. But the next day, he waited for her to come and told her about the new drug he was trying out. “It’s unlike anything I’ve ever had before”. His excitement was contagious and exhilarating; and hard to explain to someone else. It felt like he was confiding something only she could’ve known.

“I haven’t done this with anyone else,” he said. “Let’s do this together. You’re special.”

Seerat hesitated. “Joints are one thing, but I don’t know about this.”

Sahil’s eyebrows furrowed. “What do you mean? I did it first to see if it’s not dangerous. And see? I’m fine.”

“I never asked you to –”

“Seerat,” Sahil said, in a low voice. By now, Seerat knew he used this voice either when he was being emotional, or when he wanted her to agree with him. He took her hand and massaged it gently. “Don’t you trust me? I’m hurt.”

Seerat’s eyes looked at him in confusion, and then guilt.

“I know you’re scared, but look at all the adventures we’ve had,” he said, sliding his other hand near her hip. “Don’t you feel like we should blindly trust each other by now? Do you think I would ever hurt you?”

Seerat wanted to say many things. That perhaps there were other adventures they could do together, like reading a book and asking each other silly questions. But maybe her relationship with Sahil was never meant to have silly adventures, only bold, risky ones.

Silently, she took the foil from him and smiled. “I trust you.”

He smiled back. For a second, Seerat felt he was cold and distant. But then the spark returned, and she sighed in relief..

The bus headed to her destination came to the corner, and Seerat scanned the crowd around her to see any traces of maamu. None so far. She got on the bus and checked her phone. Twenty minutes to one o’clock.

She wished she had run away from Saahil.

Minute 8: Burdens to Minute 5: Resolution [Is being a criminal an eternal task?]

“Whenever I meet ex-drug addicts, do you know what they tell me? They tell me they made a mistake. A very big gamble with their lives. They cannot stop crying and asking for repentance. What does this story tell us? That at the end of the day, going for your desires, away from Allah, is all a mirage! True happiness lies in submission, and in being good to your parents. So, children, stop getting affected by satanic desires! Go pick up the Holy Book, and see how our great Prophet endured despite so many trials! He never took drugs. And neither should you.”

Seerat heard these words from a religious leader, during a school assembly session. The leader seemed to look at her directly as he spoke. Her eyes scanned the other line formations until she spotted Sahil. His face looked bored and amused.

Since using heroin, Seerat’s mind had gotten heavier. It was as if she was a child all over again – who had lost control of her body and its urges. She could restrain herself only for a day before becoming sweaty, clammy, and in pain.

It was hard to appear normal in front of her mother. Many times, Seerat would beg Sahil for some more charas drugs so she could take them home. She was afraid her convulsions would catch up with her.

“Look at you, so desperate,” Sahil said, and grinned. “But you owe me a lot now. Much more than before. Don’t forget that.”

Seerat realised it only later — but after a point, Sahil’s face had begun to look awfully like her father and maamu. He had begun ordering her around, telling her how she should live her life, his imagination drawing a line around her choices.

The leader’s voice was powerful and earnest. “We are all sinners in the face of Allah, but we should always repent and try to be our best. Talk to your parents about your issues. Come to me. We will all help you. We are in this together.”

After the special assembly, she asked Sahil if he believed in what the leader said.

“They’re all a bunch of stooges,” he scoffed. “He is the same religious leader who stood around and did nothing while my mother went crazy after my sister’s death. Every day, she would go to him and beg him for help. She even donated 10,000 rupees to his mosque. But nothing happened and he ignored us. Why should I listen to him? At least drugs help me feel better.”

Did they? Sure, maybe for a short while, but in the longer run, didn’t it feel more like a burden?

Minute 7: Ambition to Minute 6: Adulthood [Was there a way to become human again?]

The bus crept slowly as the conductor kept calling for names. Seerat looked at the young and old filing in, wondering when she would grow wiser with age. She knew she had been immature and stupid in many of her life decisions, and just like any other person, she had regrets.

Would those regrets ever go away?

At some point, the principal had been notified of how the abandoned building was being used. Rumors surrounding Seerat grew louder, as her face grew more gaunt. The school administrator began using the building for his smoke breaks and keeping a check on students passing by. Seerat could no longer meet Sahil.

Not that she needed to. He had introduced her to his drug peddler after getting annoyed at her constant requests. Right after the administrator started coming to the building, Sahil took a leave of absence.

Nobody knew what the absence was for, and when he would come back, but hardly anyone cared. At first Seerat felt she was obligated to care, but after a while, she began to feel quite far away from him.

Just as suddenly as she had met him, they had parted — like strangers passing through the night. She never contacted him, and he never reached out to her. Sometimes, she would ask the drug peddler if Sahil had called.

“Are you in love with him?” the peddler would tease. “He’s charming, for sure.”

Seerat didn’t know how to respond to that. Did she? Were they in love?

Did two people in love inject drugs like they used to? If they were in love, was it a crime? Or an unhappy circumstance?

Seerat got out of the bus and walked a few metres. The main gate of the hospital was wide open.

She checked her phone. It was two minutes till one o’clock. She walked to the OPD, her mind flashing with images of soi, joints, laughter, Tulip Gardens, Eid, and harissa. It felt like she was walking towards her death.

Seerat got to know about the hospital drug de-addiction scheme during the special assembly. At first, she fought with herself and tried to give herself a deadline to go clean up. But as time passed, and her mother battled another addiction, she couldn’t help but feel she had broken the family apart.

Maybe her father hadn’t disappeared, but left because of her. Maybe she was never meant to be loved.

Seerat sometimes wished she had a younger brother or sister to take care of. Perhaps, she would’ve been less rash in her decisions. Maybe, her mother would’ve been more present.

Her footsteps grew heavy and as she reached the counter, a tired face peep from behind it.

“What do you need?” the receptionist asked dully.

Seerat gulped and took a deep breath. With shaking hands, she said, “I’m a drug addict. I need help.”

The woman receptionist nodded as if it was the most normal thing in the world to have an addiction. Immediately, she took out a form to fill out and started asking questions.

“When did this start?”

“A few years ago.”

“How many? Years, I mean.”

“…five.”

“What kind of drugs have you used?”

“Marijuana, mostly.”

The receptionist looked up. “Mostly?”

“…and heroin.”

The receptionist nodded again. “We’ll have to take some tests. Do your parents know?”

Seerat shook her head.

The receptionist’s mouth twitched. Ah, there it was. The look of judgement. Seerat was used to this. Beside her, a stranger — an older man — came to stand, resting his hand on the counter and leaning in to listen.

“You will have to do a couple of tests,” the receptionist said. “For hepatitis. Did you share a needle with your lover?”

Seerat felt her stomach slowly churn at the receptionist’s words. How did she know it was a lover? Had someone been keeping tabs on her?

“Did you share a needle or not?” she asked irritably.

“…we did.” Seerat felt she had confessed to a crime.

The man beside her glared at Seerat.

“Hepatitis? Are you a drug addict?” he said.

Seerat was surprised and didn’t respond.

“Are you her father?” the receptionist asked.

The man ignored the official. His voice began to rise. “Do you have no sense of dignity? Give me your father’s number and I’ll talk to him!”

Seerat closed her eyes and hung on to her scarf as hard as she could. She couldn’t let the man see her. Unless, was it her father? Was this how he would’ve reacted if he knew what she was like? Was this the punishment of a crime?

The receptionist immediately stood up and came around the desk to push him away. “Uncle ji, please stop right now, or I will have to call the police.” A crowd gathered around the three.

“You’re no different!” he shouted. “How could you admit such a vulgar woman in our premises! What has our community come to? This woman has the nerve to wear the sacred hijab to cover her face! Her actions are far from being modest! Go to hell, both of you!” He spat on the ground.

“What’s happening?” A woman wearing a burqa asked. “Why are you disrupting the peace here?”

A younger man came in between Seerat and the older man and put his hands in front of them. “Uncle ji, calm down. This is not a place to have this conversation.”

“I’ll go to her house and tell her parents what she’s up to! Don’t tell me what to do!” The man shouted. “What’s your name? Where do you live? Spit it out quickly.”

“Are you her relative? Why are you so interested in her life!” another woman amongst the crowd said.

The young man put his arms around the older one. “Uncle ji, let’s have a conversation outside. You can tell me all about it. Stop this now.”

“But —” the man said.

“Yes, yes, you are right, she’s entirely at fault,” the younger man said, with a tone of amusement, the kind used to talk to a child. “But let’s not talk about it here. Let’s do it outside.”

The two went, with the younger man holding a firm grasp on the older man’s shoulders and leading him towards the exit. The crowd made off-handed comments before dispersing shortly.

The receptionist held Seerat’s shoulder and bent down to look at her. “You can open your eyes now. He’s gone. Don’t worry about him, he probably has nothing better to do.”

Seerat opened her eyes. The man’s force could still be felt on her head. She blinked back tears.

“Don’t cry,” the receptionist said. She went back to her seat and gave her the form. “If you’re going to feel regret now, think about how your mother and father would feel if they knew you were like this. Go take a seat. Your number is 25. I’ll call you shortly for the tests.”

Seerat waited for her to say something — anything to explain the casual violence of the situation — but the receptionist bent her head and stared at the computer screen. Wordlessly, Seerat found a few unoccupied seats not far away, and sat down.

Did she make a mistake by coming here? Had she placed too much trust in a system she had no idea of?

She looked around herself to see whether there was anyone like her. She saw mostly older men and women, some of whom were staring like her. She tried to find women her age, sitting like she was, hiding their faces from the public. Instead, younger girls ran around the waiting hall, entertaining themselves with hide-and-seek giggles as their caretakers waited for their turn. Seerat closed her eyes briefly and hoped she could transport herself into an older man’s body. Would her choices be more bearable then?

“Sorry about that,” a familiar voice said as if speaking to her. She opened her eyes and saw the young man looking at her. The one who had escorted the older man outside. “Don’t pay attention to him. Are you okay?”

Seerat was surprised at his kind voice and nodded.

“Do you want some water?” he asked. “I was going to get some for myself anyway.”

Seerat hesitated but nodded again. He smiled and left. After a few minutes, he came back with a paper cup and gave it to her. “Are you from Srinagar?”

She shook her head and slowly raised the dupatta near her chin for a sip. He sat next to her in the empty seat.

“Are you alone?”

She nodded.

The young man drank some water. “I’m not here to pry. I just felt bad after what happened and wanted to check in.”

Seerat said nothing.

He looked at the ground and crumpled his cup. After a pause, he said, “I had a friend…who died from an overdose. He never told me…he was struggling so much. I only got to know later…he was a lively person, but he got involved in something reckless.”

Seerat turned her face to look at him, intrigued.

“I wish…I had done more,” he said and got up.“ We Kashmiris have a habit of keeping our suffering a secret, but we don’t need to. I could’ve helped him if he had just told me. I think it’s very brave of you to do this, to take a chance with yourself. That old man knows nothing about what you’ve been through. Just keep going.”

He got up and smiled at her, before turning back and walking towards the exit.

Seerat looked at his retreating figure with a question burning in her throat. Was that friend Saahil?

Noon: Acceptance

On one fine day when her mother was cutting vegetables in the verandah, Seerat sat next to her. She watched her mother’s droopy eyes quietly inspect each spinach leaf from their garden, before cutting it into shreds.

Seerat felt like opening up. It seemed like the sort of quiet, normal day that could handle a truth like drug addiction. The chirping birds promised to fill the fearful pauses.

So she did.

After listening to her, her mother looked at her and sighed. “Whose fault is this?” she asked, to no one in particular. “Yours, mine, your father’s, or Allah’s?”

Seerat stayed quiet, sitting next to her. She didn’t know what to say. She got up and cut some soi from the garden and placed it in front of her mother’s hands. Maybe, this was the answer her mother was looking for.

Her mother’s eyes widened, looked at Seerat, and then looked down at the soi. She sniffled quietly.

“I think it’s mine,” her mother said after a long silence. “Who else would society blame? Who else can I blame?”

Shortly after, her maamu came, with a different and more concerned look than the one he usually wore. He sat Seerat down and stared at her for a long time.

“I have tried my hardest to be there for you,” he said. “More so than my own family. Your father –” he stopped and sighed.

Seerat felt a strong need to lash out. “Where’s my father?” she asked. “Do you know? Have you kept him from me? Did he leave because he knew I would become a drug addict?”

He looked at her for a few minutes, as if he was assessing her ability to hear the answer. And then he opened his mouth.

“I’ll show you.”

During the few times Seerat had rode in maamu’s car, she had never cared much about the destination. This was the first time she felt anticipation. After the drug, her senses had dulled, but today, they were heightened. It was evidence that she felt the need to know.

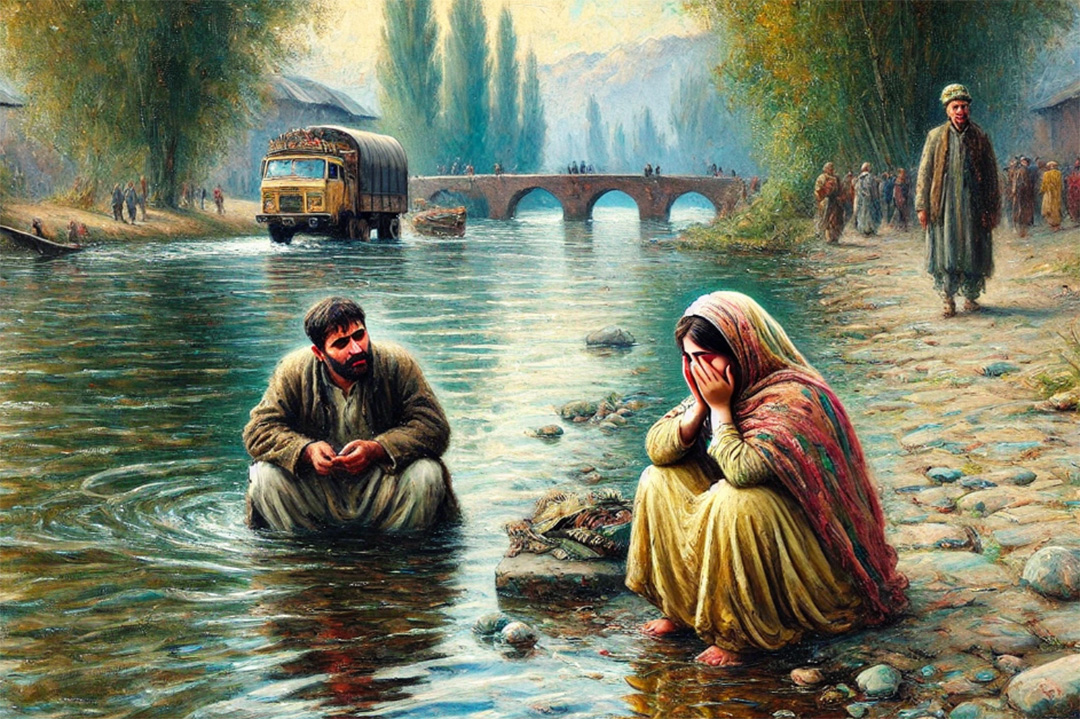

She recognised the old lanes and the familiar shops – Ganai Medicines, Panun Shop, Mir Electronics. They were going across the Jhelum river.

Her maamu remained tight-lipped during the entire ride. His hands were gripping the steering wheel as if he was telling himself to complete what he had set out to do. He drove calmly and stiffly.

As they approached the overflowing banks of the river they all loved, her maamu made an abrupt stop. He stayed quiet, his eyes refusing to look at the murky waters. Seerat looked at him and said nothing.

Slowly, he got out and signalled her to do the same. They walked down the muddy path, as cars rushed behind them. The water continued to flow, unperturbed by the new presence. Her maamu stopped just short of the water bank end. Seerat stopped beside him.

They stood quietly; one waiting to speak, the other waiting to listen.

Finally, her maamu spoke. “He’s here. In the Jhelum.”

Seerat crinkled her face in confusion. For a few seconds, she didn’t understand. She looked at him, waiting for a better explanation.

“He was put inside the Jhelum,” he said again, emphasising ‘put’. He waited for the realisation to come.

And it came. Strongly. He saw her face contort in horror, sorrow and anger all that once. She looked at the water and then at him, eyes accusing him of hurting her in order to tell the truth.

“It wasn’t a suicide,” he said, looking at her tenderly. “You have to know this.”

Seerat felt her legs shake. She bent down and stretched her hands out into the water. She touched it. It felt like Baba’s clothes.

“If there’s charas (hashish) on earth, it is here, it is here, it is here,” a voice abruptly said behind her. Both her maamu and she looked towards the source of the noise. The red-eyed face of a boy, his back against a tree stump, looked back. He was grinning, but he looked unhinged. Alien, even. Seerat noticed the boy’s soft grip on a syringe. Her maamu noticed it a few seconds later. His gaze changed to rage. Hers changed to grief.

Without breaking eye contact with the boy, Seerat began to sob. Flashbacks — of Saahil, of his forceful hands all over her, of her own frustration with her mother — began to overflow. She tore her gaze away to look at the Jhelum. She sobbed louder.

At that moment, she felt she had seen her entire life: wedged between her own choices and the desire for freedom. She could say it was her trauma, it was Baba’s fault; but after touching the water, nothing came out. She was reunited with Baba, but his essence had disappeared. He had left her with no wisdom, no note, and no way for her to move forward.

The boy’s cackling and lazy laughter filled the silence along with her sobs. Her maamu couldn’t ignore his rage any longer and spewed insults at the boy.

“Which community do you come from? Shikaslad! I’ll find your father and tell him all about this! How dare you do this to your life!”

Seerat looked in surprise at her maamu. She had never heard him speak this way. She was reminded of the old man in the hospital. She reached out to his hand.

“Don’t talk like that,” she said between sobs, “Let him be. Or he will kill himself.”

Her maamu looked at her with exasperation. And then regret.

“I shouldn’t have brought you here,” he said. “This is my fault. How will I face your mother now?”

“Take me home,” she said, standing up and wiping her tears with her scarf. “I don’t know what’s happening to me.”

Her maamu took her home. Seerat was too delirious to remember the rest. She collapsed on her bed, shock seeping into her body.. She came in and out of consciousness through the night. Sometimes, she heard her mother’s quiet sobs. Sometimes she heard Saahil’s laughter. Other times, it was just silence, talking to her, telling her about her sins.

Somewhere in the midst of her delirium, Seerat saw her younger self speaking to her. What was her sin? What crime had older Seerat committed?

Was yearning for love, for growth, for money and a good, trauma-free life, a crime?

For two days, Seerat’s deliriums and her conversations with younger Seerat stayed. In her imagination, her younger self kissed all her punctured veins and fed her sweet sherbet. When it was time to go, younger Seerat hugged the older Seerat. The hug smelled like the mother she knew — soft, sweet, and frustratingly disciplined.

When she woke up, Seerat stood up from her bed and sat in front of her small mirror. She stared at herself for a long time. Her mother came and combed her hair. She recited some verses of the Qur’an –

“Guide us on the Straight Path,

the path of those who have received Your grace; not the path of those who have brought down wrath upon themselves, nor of those who have gone astray [Surah Fatiha:7]

She blew the verses on her head. She sprinkled some holy water on her feet. She fed her food.

Seerat closed her eyes and saw Baba’s face. He was waving at her, telling her to find her inner beauty.

It was time to let go.

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

Draw a picture of an addict. Would their hair be unwashed, their eyes bloodshot, their lips colourless and parched, their face gaunt, probably male? Perhaps you imagine them in their 20s. Perhaps you believe they are ‘irresponsible’.

Why is the idea of an addict so uniform in our imaginations? Is it due to an ingrained belief system? Do we perceive them as individuals from ‘good families’ yet influenced by bad friends? Do we picture them as victims of poverty, using the only respite available to them? But do we ever think of addiction as the by-product of conflict?

We wanted to look at addiction in Kashmir from a woman’s point of view. Layers after layers of systemic failures opened up. Most women would rather seek rehabilitation outside their state than risk the stigma at home. The absence of women-only de-addiction centres, the omnipresent fear of being recognised, cultural complications and the daily challenges of life in Kashmir only scratch the surface of the issue.

We’ve tried to blend the unique socio-cultural facets of addiction among Kashmiri women through two primary profiles. One represents the young woman seeking connection through substance use with a violent partner. The other, a middle-aged woman, finds herself inadvertently dependent on prescription medication (you can read more about this) due to trauma. Both women face the experience of addiction, which isolates them, but also reveals a deeper psycho-geography of Kashmir.

Both women struggle to find avenues for validation, dignity, and reconciliation for themselves.

While I end the story with Seerat resolving to stop her journey with addiction, reports show more instances of relapse, often leading to death from overdose. Mental health professionals face a staggering pandemic of deaths with little to no resources, and strict cultural attitudes to tackle. Meanwhile, unemployment, the absence of healthy avenues and mentors for recreation, support and growth, as well as rigid gender roles remain strong factors for young people to choose addiction in Kashmir.

It is a bleak future. The quicker we accept it, the quicker we can gather resources, build strategies, and co-create to explore and support Kashmiri women in building a future they imagine for themselves and deserve to have. This is the anatomy of a drug-abused Kashmiri.

Resources:

Women-centric data:

- Ministry of Home Affairs. (n.d.). National data of use of drugs and arrest in Jammu and Kashmir.

- International Journal of Advanced Medicine. (n.d.). State-level research on prevalence. Retrieved from

- ResearchGate. (n.d.). Awareness of drug addiction among college students of Kashmir Valley.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2008).

- Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. (2019). Use of inhalants and drugs in India: Book on 08.05.2019.

- National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Drug misuse causes major problems for women in India. Retrieved from

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2018). Global Report on Women and Drugs: WDR18_Booklet_5_WOMEN.

Help:

Helplines [National and Hospital]:

IMHANS: +91 194 241 0037

SUKOON Helpline: 1800-180-7202

National Toll-Free Helpline: 14446

IMHANS Child Guidance and Wellbeing Center: 9419683109

Government Medical College, Baramulla: 9419982645

SMHS Hospital: 0194 250 4793

Helpline [Drug De-Addiction]:

AAGHAAZ Deaddiction Center: 091496 22795

HNSS Drug Rehabilitation Center: 097969 15900

Helplines [NGOs]:

CAUSE: 91038 88755

Helping Hands Foundation: 7006060077

White Globe: 097971 60070

Other resources:

Low-cost community-based care for drug users: UNODC Toolkit_1 (Module 6)_16th May 06.qxd

Read in Hindi.