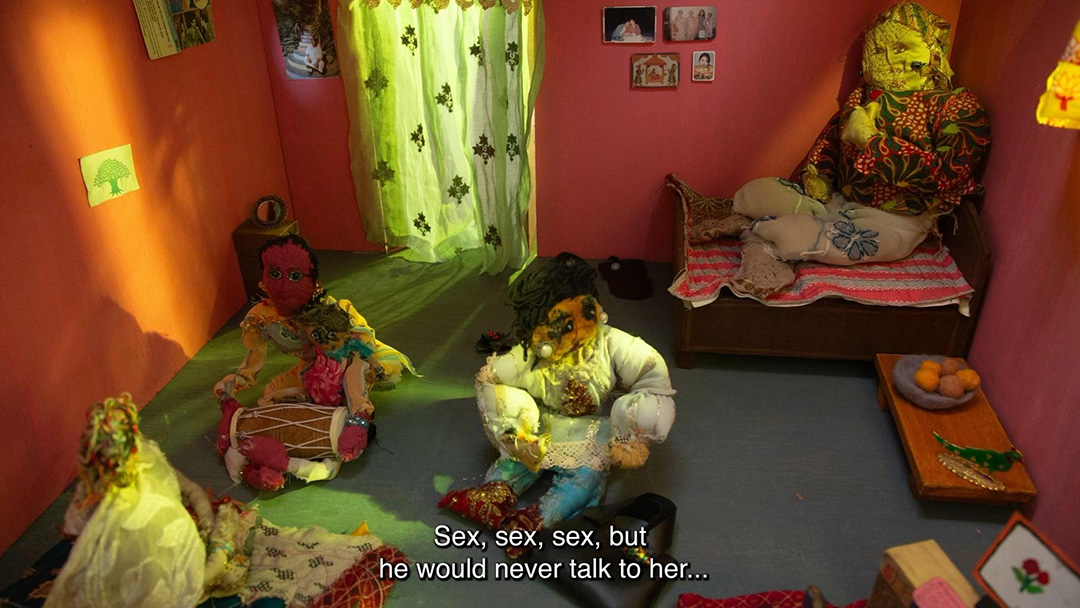

When filmmaker and doll maker, Hansa Thapliyal, worked with The Third Eye’s Learning Lab on creating a mixed media film out of the recordings of workshops for the Caseworker’s Dictionary of Violence, she asked, “Will I be able to go where these voices are?” Hence emerged Kya Hai Yeh Samjhauta? which works with the material of the everyday, scraps of cloth, needle thread and the timbre of human voices to bring alive the technicolour landscape in which womens’ compromises rest. From Veena Das and David Lynch, to the bylanes of Banda and the kind tailors of Amar Colony market, read on to find out what went into bringing this tapestry to life.

Is this a documentary?

TTE: We were developing our project around the Caseworker’s Dictionary of Violence, and that’s when you came in. We shared all this material with you. Now, documentaries about violence tend to focus on a particular case, a survivor or a victim — the entire film is centered around that story. It reveals certain truths, and realities to the viewer: about power, about structures. But this film isn’t centered on one case… in fact, its mixed devices make you wonder.

So, in that sense, do you think this is a documentary? What kind of documentary would you call it, if at all?

Hansa: Honestly, I don’t know whether it’s a documentary or not. Sometimes, I wonder. But if you think about it, all the documents that came to us — everything we received — it’s all there in the film. So, in that sense, maybe it is a documentary?

You know how a geetmala works? Bahut saare geet aate hain, phir geetmala bann jati hai — it’s a collection of songs that comes together to form something larger. This film is a bit like that. A whole lot of material came in, and I think the form grew out of that material, rather than from a pre-existing plan.

I have personal inhibitions about interviewing people as a filmmaker. It’s not an objective stance; it’s not like I believe interviews shouldn’t be done. It’s more about my own personality, my discomfort with that kind of direct questioning. But here, the interviews had already been done, so that was a relief.

The biggest challenge was compression — how do you condense all of it into a short piece? I think more than anything else, what carries the film is the way the women have taken to the dialogues we wrote, and etched them with their voices and experiences. The film bears their presence. It’s validated by them because they participated at every stage.

You were working with them first, then we worked with the material you brought in, and then the women themselves did the conversations. That entire process — of collaboration, of layering — shaped the film.

I too had my own responses to the images the women sent — of themselves, of their spaces, their colours, their love for clothes. All of that gathered together to make this form.

So… Would you call it a documentary? I mean, a film is a film.

Every film is a documentary in some way, no? Even if you watch Raj Kapoor and Nargis on screen today, they cannot escape being who they were.

Their presence as human beings remains, whether they were acting or not. So, film ka nature hi aisa hai — it always carries something real. But that’s a different discussion. In this case, I think the film gathers everything — voices, materials, traces of the women’s lives — and compresses it into a form we can all feel happy about.

On Violence and Reparation

TTE: The Raj Kapoor-Nargis example was lovely. So, when you started making this film, did you always think of it as a film about gender-based violence? Or did something else drive your approach?

Hansa: I was very much aware that violence had a presence in this film. It had a path. That’s why I asked for reading material, which led me to Veena Das and Megha Sharma’s academic paper on Small Hands — that paper really helped me think through things.

But to be honest, dealing first-hand with the experiences of these women was too difficult for me. I didn’t know how to tackle it. It was so outside the realm of my own experience. But the readings helped because they were simple, evocative and suggested that if you stay with the material, you can participate in it.

At the same time, I was working on Mallika Taneja’s play Do You Know This Song?, and teaching documentary filmmaking in Rohtak. These different projects became invitations, they welcomed me into different worlds.

We weren’t trying to represent violence directly. Instead, we focused on the act of repair.

On Cloth as a Central Medium

TTE: Is that why cloth became the central visual medium in the film?

Hansa: Yes, certainly. Although I didn’t realise it at first. Later, I remembered an image from the anti-CAA protests — someone had created an image of women mending fabric. It wasn’t a conscious decision — it wasn’t like I thought, “Oh, that image from the protests, let me put it in this film.” But somewhere, it must have stayed with me.

Also, I personally work a lot with cloth. I like working with scraps, with the act of mending. Even before this project, I had a friend who used to darn fabric, and she spoke about how darning meant something deeper to her — how it was connected to what was happening in her life.

I think we all experience this. whatever processes we engage with — whether it’s cooking, stitching, or anything else — we link them to our lives.

We find metaphors in our daily work, and we console ourselves through them.

But the decision to use cloth in the film wasn’t only about repair. It was actually about how much the women themselves loved cloth. When I asked them for WhatsApp messages about things they liked, there was so much cloth — so many sarees, fabrics, textures. They had deep relationships with cloth. So, when we were looking for material to animate, it became obvious: cloth is the material to go with.

And from there, of course, the idea of repair emerged naturally. The material itself started giving us solutions. I once worked with a dollmaker who told me, “The material talks to me.” And I think that’s true. Once you start playing with it, once you start working with it, the material guides you.

On Caseworkers as the Central Figures

TTE: In films around violence, the central figures are usually the people who have faced violence themselves. But in your film, the focus is different. The caseworkers are not only survivors of violence — they are also intermediaries. They navigate between women who have faced violence and the State, the law, families and society.

Did knowing this — the fact that the film is centered on a collective, a collection of voices — push your script orcraft in any way? Did it challenge you?

Hansa: Oh, absolutely. There were so many voices in the interviews you shared with me, and it became a challenge to listen carefully — to hear the different cadences, the variations in tone, the different ways in which women spoke about their lives.

Even in the addas you shared, I would watch the women in the frames and think, “Achcha, this one has chosen to stay home, that one has moved away, this one loves lipstick.” You’re constantly observing.

There’s something magical about allowing those things to blend together, about trusting that they are already connected in some way.

The women I saw in the interviews, the women I saw on the street in Rohtak, women from my own life — all of it flowed together in the making of these dolls.

The fact that the film was centered on caseworkers also made it easier, in a way. Because they have already gone through their experiences, and now they are talking about them. They are sitting together, chatting, reflecting. And I am simply listening in on their conversation.

At one point, it almost became like a gudiyon ka khel — a game of dolls. I would imagine their daily lives: “When she goes out in the sun, does she carry a bag? What does she keep in it?” Those little details became important.

I remember one particular interview — was it Manju? I’m not sure now — where she describes standing on the roadside, seeing an air-conditioned car pass by, and feeling a sense of contentment. She was out doing her work, in the heat, and yet there was a quiet joy in that. That moment stayed with me.

So we started working with your photographs of the caseworkers in their everyday spaces. We animated them walking, sitting, taking selfies. That was fun. It allowed us to relate to the dolls in a deeper way, to think of them as people in motion, with personalities, with lives.

On the Tapestry Metaphor and the Filmmaking Process

TTE: The tapestry is such a central visual metaphor in the film. Do you see your filmmaking process itself as a form of weaving?

Hansa: Oh, absolutely. But it was a wild, chaotic tapestry! (laughs)

The whole process was like that. I thought I needed just one assistant, but we ended up as a unit of five people, all continuing to work together. We were in different places — Shivam and you were part of the unit but also connected to The Third Eye, and we were working in this decentralised, layered way.

It really was a beautiful experience. And the film itself has been so kind. She’s been shining here and there — travelling, being seen, being loved.

You know, when I was younger, I read Salman Rushdie’s Shame. I never finished the book, but I remember this description of an exquisitely embroidered shawl. And in my head, I would dream of making something like that.

I was never good at embroidery — failed all my needlework assignments in school! But somewhere, that fantasy of weaving something intricate, something layered — it stayed with me. And with this film, I think I found a way to realise it in my own way.

And, of course, all of you were open to this method, which made the process even more beautiful.

I make dolls — it’s a strange little thing I do. But with this film, those dolls found their own purpose, their own role. They became part of the storytelling.

On Violence, Longing, and the Act of Leaving

TTE: There’s a moment in the film where the character moves back and forth — it feels like she is caught in a loop, in this constant push-and-pull. For me, longing became a central theme in the film, apart from violence. Could you talk about that? Was there a particular moment that inspired this?

Hansa: Oh yes, absolutely. That movement — going back and forth — was very much present in the interviews as well.

And, you know, I’ve also known someone personally who was going through a very rough domestic violence situation. That experience — watching her navigate it — really gave me the strength to feel, “Okay, I know something about this film.”

It’s exhausting, no? To keep looking for a place where you can finally rest, but never be given that rest? That’s what the movement represents

The constant cycle of leaving, of returning, of trying to find something better, only to be pulled back again.

We all long for something, even when we don’t always know what we are longing for. And in cases of violence, that longing becomes sharper — it crystallises into something urgent.

In the interviews, too, I remember hearing this theme over and over again — women speaking about the act of leaving, about the impossibility of leaving, about the yearning to move forward. And that’s what informed that moment in the film.

On the Sound Design and Creating Atmosphere

TTE: The sound design in the film is so striking. It builds such a strong atmosphere. Can you talk about how it developed?

Hansa: Oh, that was all Amir Musannar’s work — this was his first time doing sound design, and he did phenomenal work.

I remember we were discussing Eraserhead, David Lynch’s film. I told him, “You know, I used to love that film.” And, I think, something from that conversation must have stayed with him.

At one point, he added a placeholder track — some music, some reverb — and I was shocked. I had never dared to put that much reverb into such an emotional moment. But it worked.

We also referenced Pakeezah and other old Hindi films — the way they use sound, the way they allow emotion to expand. Some of that openness to emotion really helped us find the right balance in the sound design.

And, of course, we played with a lot of ambient sounds. I remember Shivam rewatching the film and noticing this faint sound of a wedding procession passing by. It’s almost imperceptible, but it’s there. That kind of layering — those tiny, almost invisible details — that’s what helped create the atmosphere of the film.

On the Final Scene

Hansa: You know, there were moments in the film that I didn’t even direct, technically speaking.

That final scene — where the caseworkers are in the garden — I think all I said was, “Take them outside and let them shoot each other.” That was my only instruction. And then when I saw the footage, I thought, “Jesus Christ, how did they come up with this?”

Shivam (TTE): The brief we were given was that we had to make use of the actual shawl — the real one that had been worked on by the caseworkers. We had to show them accepting it, wrapping it around themselves, and owning it.

I think the choice of location played a big role. It was summer in Banda, Bundelkhand — that specific kind of summer, with the heat, the dust, the stillness.

We wanted a quiet space, a place where they could just be. And in that space, they started interacting with the shawl for the first time — playing with it, trying it on, laughing. That energy seeped into the footage.

There was one moment — Manju wrapped the shawl around herself, and suddenly, she was completely still. She lowered her head, looking at the fabric, and for a moment, it was like she had retreated into some private space. That moment told us everything.

We decided to capture those emotions in slow motion — right there, in-camera, not in post-production. That decision gave the scene a certain weight, a certain poetry.

Hansa: It was beautiful. And the fact that you captured all of that organically — without over-directing or imposing an idea onto them — made it so powerful.

On the Word ‘Samjhauta’ and Its Meaning in the Film

TTE: Watching the film this time, I kept thinking about your relationship with the word samjhauta (compromise). When we were working on the Dictionary and developing the material, we had different relationships with the word. But your film doesn’t demonise the idea of samjhauta. It doesn’t see it as just an act of surrender. It complicates it.

So I’m curious — what does samjhauta mean to you?

Hansa: Oh, that’s a great question.

I think I wanted to remove any shame associated with the word. That must have been a conscious decision. And I also wanted to allow for a certain porousness in the meaning. Because samjhauta is not always about surrender, no? It’s also about survival. About negotiation.

I dislike the English word compromise. It feels too rigid, too final. But samjhauta — there’s something more fluid about it. It allows for movement, for transformation.

Most of us experience life in a porous way. We move through different phases, we absorb things, we change. We become different creatures over time. And the word samjhauta carries all of that within it.

On Who the Film Is For

TTE: I think you’ve given the feminist reading of samjhauta — the idea of porousness and negotiation. That’s exactly what a lot of the caseworkers wrote about, too.

As a parting question, Hansa — who do you think this film is for?

Hansa: I really, really hope that it works on the ground. That it reaches the women it was meant for. Of course, it’s been a bonus that the film has travelled to festivals. That’s been lovely. But my real hope is that it resonates where it matters most.

As for the future — yes, I’d love to keep making films that feel urgent, that feel needed.

This film was made without overthinking. There was no second-guessing. It was done with complete immersion, with complete trust in the process. I think that’s why she turned out to be one of my kindest children, this film. And of course, she’s not just mine. She took a whole village to raise — several villages, in fact!

Hansa Thapliyal is a film maker who has been trying to work with materials, to bring a feeling of tactility to her images. In the last many years, she has been learning by working with artists from traditional theatre groups— Surabhi from Telangana and Thakkar Kala Aangan from Maharashtra; by making a film on two doll makers (The Outside In), creating doll making workshops, and teaching film. She enjoys working with diverse forms of language, has been supervising Hindi translations for Agents of Ishq and worked long on Kamal Swaroop’s project, Tracing Phalke. She is the dramaturg for Mallika Taneja’s theatre piece, Do You Know This Song.