As part of The Third Eye’s Public Health edition, we spoke with a wide spectrum of experts, community leaders and practitioners — what works, why it does, and what an equitable public health system could look like.

Menaka Rao is an award-winning journalist who has reported extensively on health, nutrition and justice. She has reported extensively on tuberculosis, including aspects such as the gendered delay in diagnosis and treatment of TB patients and the origins of drug-resistant TB in India. She won the Mumbai Press Club Award in 2018 for her series on a fatal malaria outbreak in rural Andhra Pradesh. Here, Rao talks about her journey as a journalist reporting on the big, complex and often baffling institutional arrangements that are supposed to ensure our public health and how sometimes their inflexibility and lack of egalitarianism can lead to new health crises.

Can you tell us a little about why you do health journalism?

I was doing legal reporting at a newspaper in Mumbai and got bored. I thought that health reporting would be more challenging. I had started reading seriously then and wanted something broader: a change and a challenge. I thought health would be a good fit. I was into science to some extent.

Back in 2006 or 2007 health reporting in cities was like – here is this unusual surgery in this hospital! It was basically a lot of press releases. I had been a journalist five years by then and this was completely new to me. Oh, you know, this fantastic thing happened in this hospital and I was like, ‘This sounds like rubbish.’ Or you were sent to cover accidents or building collapses. It was hard back then to see what a health story looked like.

Legal reporting happened within a fixed space. With health you have to really spread your net very wide, speak to a lot of people. I started going to Bombay’s four or five public hospitals and for a long time, I didn’t know what I was doing. The learning curve was very steep. I was refusing to write those press release stories and I was unable to find any new ones. I was a little stuck for a while.

Then I got a break. Dr. Zarir Udwadia [the Indian pulmonologist who has done path-breaking research on TB] wrote a letter in a medical journal saying that Mumbai had cases of TB which were entirely drug-resistant. That’s the first time I saw a problem I could really get into. And that’s how I went to the TB hospital for the first time. Reporters did not go there back then.

Health was considered a ‘soft’ beat, right? How does it affect you as a journalist if the beat is considered ‘soft’?

When I was doing daily legal reporting, it was taken very seriously. And daily legal reporting is actually quite easy to do. You have to go to one space and collect information and come back and it’s not that hard. Straightforward and easy at that level. You just have to be accurate, which is a basic requirement for journalism [laughs]. I have had crime reporters say things to us health reporters, you people do PR, right? I used to be shut up, I have done legal, okay? Legal and crime journalism is a well-oiled system. It’s not that hard.

But there is a lot of macho behaviour?

Yes, there is a lot of macho behaviour around crime reporting. Health reporters are usually women. The occasional man in health reporting is usually covering pharma as an industry.

How does this affect your work?

I will give you an example from when I was reporting in Bombay. On Holi, usually nothing happens in newsrooms. One Holi, in a particular area in Bombay, a lot of people started falling ill. At first nobody could understand what was going on. And then they figured that there was a poisonous dye that had been used and was getting absorbed through the skin. It had an antidote, which somehow one major hospital had figured out. Other hospitals had not. There was the usual disparity in the way in which people were treated. And there were one or two deaths also. While all this was going on, the paper I worked in decided to go with a crime copy on page one. Some conspiracy story about why this particular colour was distributed in that area. It was a nothing story.

I remember having proper arguments then. It was clear to me that the health copy should be on page 1. So many people had been affected, but no. It was the crime copy that went that day. I had a clear news angle but they refused to take it. They do prioritise crime and politics. Covid-19 may have changed some of that but even now if there is a big Covid story or a political story, the big political story goes on page 1. There’s a very big hierarchy.

If you think of health journalism over the course of your career what changes have you seen [since] pre-pandemic? Or do you think any changes that have happened, have been forced on health journalism because of the pandemic?

I think editorial is definitely taking health more seriously. Today, sometimes the editorial may even overdo it; take anything that is Covid-based even if it is not important. Reporters also like thinking harder. They are looking more at inequalities and looking at how the system treats different people differently and how the health system looks at the poor. I don’t know if I had that in my second year or third year of reporting, I’m not sure. Or it’s Delhi [where I work now] where a lot of organisations do give reporters more theoretical inputs and context.

If we may use a parallel after the 16 December 2012 gang rape, suddenly the papers were full of rape reporting for a year but there wasn’t any broader thing about gender or even just women’s lives in any way. Just the same sexual violence stories, and in a sort of an unthinking way. Now, when you read the papers, or you look at the news in general, do you feel like all the health reporting is focused only on Covid?

I don’t think it’s as narrow as it was after December 16. I feel people are thinking more about this in different ways. I think health reporters have stepped up. People are more sensitive to class. I read that story about a Meerut hospital for instance. The reporter had found out that the hospital had reached a stage where patients had to bring their own cot. They may not be attuned to some kind of sensitivities but the reporting does reflect much more of what people go through. It can be better. I think people have just gone through so much this year that they’ve learned a lot. That’s what has changed.

You said that in legal journalism, the system is very apparent, a well-oiled machine. But in health you have to teach yourself to even identify what goes into the big picture. Over the course of your career what did you learn about the public health system?

Back then I’m pretty sure I didn’t know what a PHC was. I had to learn everything slowly. I mean, there are so many things that keep happening.

And there are so many things the government spends money on that we have no clue about. Like there is kala azar in Bihar, nobody would notice. It may come to mind when you find out they use the same drug for kala azar and black fungus. Or the government gives away some homeopathic medicine in Manipur, and nobody knows anything about it.

It's a very haphazard. There is no system. And whatever slightly predictable systems are there exist under the National Health Mission, the PHCs, UPHCs. The rest? Anything can be happening anywhere.

Urban health systems are a mess. That is something I have understood more clearly after moving to Delhi. I may not have understood when I worked in Mumbai because the BMC there is pretty good.

In rural health, under NHM, you know there is a PHC or that the ASHA worker will do this. Urban health systems are a bigger mess because they’re [totally] run by private hospitals. The entire urban poor is completely underserved. Nobody really knows what’s happening. In Delhi, we didn’t have any contact tracing. There’s a reason for it, because there is no unified system. One municipal body has a central government hospital. Another has a state government hospital. Some health verticals are run by the state. Others by the centre. There is no uniformity. If there’s a public health emergency, in some ways, cities are worse. Because you may get treatment, but for prevention and control, it’s crazy.

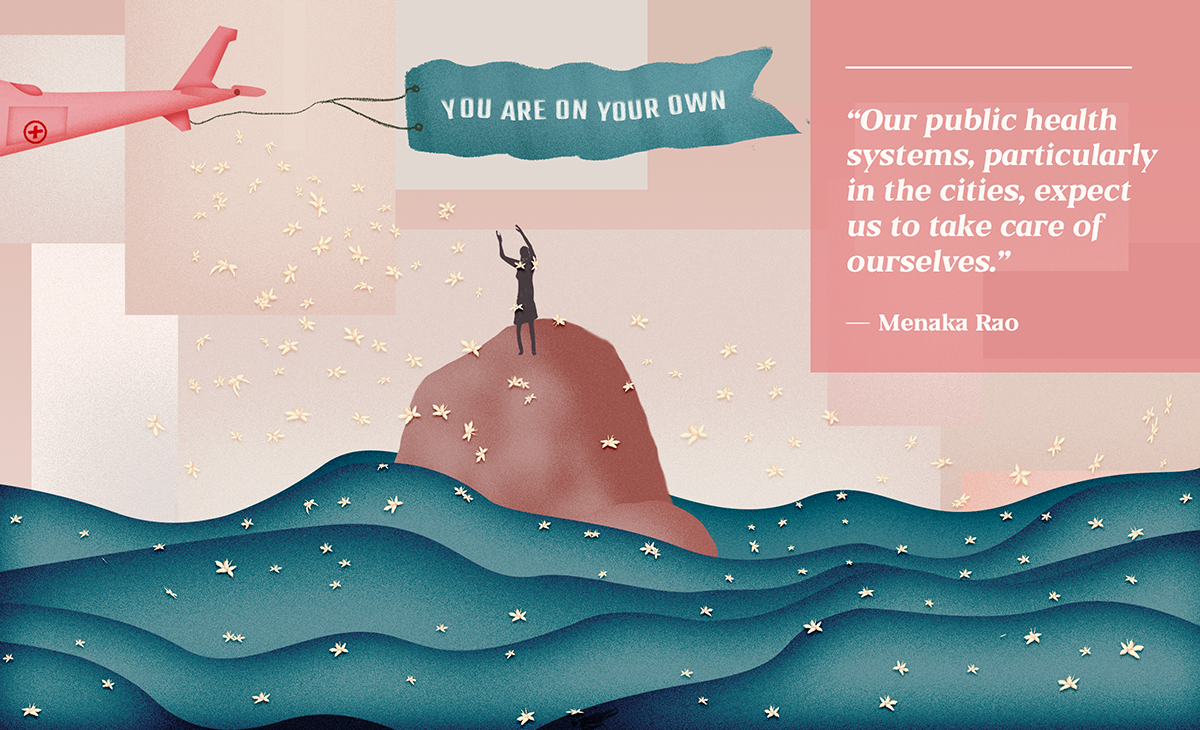

Apart from all the other problems of low funding and no manpower, the biggest problem of the public health system is that there is no system. It is run on the belief that people just take care of themselves. If you can’t take care of yourself then they are like we will see what we can do. But it's mostly run on that belief that things just happen or things just work out. Very little happens deliberately.

How would you define public health?

People feel that public health is mostly about treatment, but it’s a lot about general wellbeing and prevention. That includes obviously, vaccinations and stuff, but also stuff like, you know, a regular check-up, telling girls about menstruation or educating you to take care of yourself.

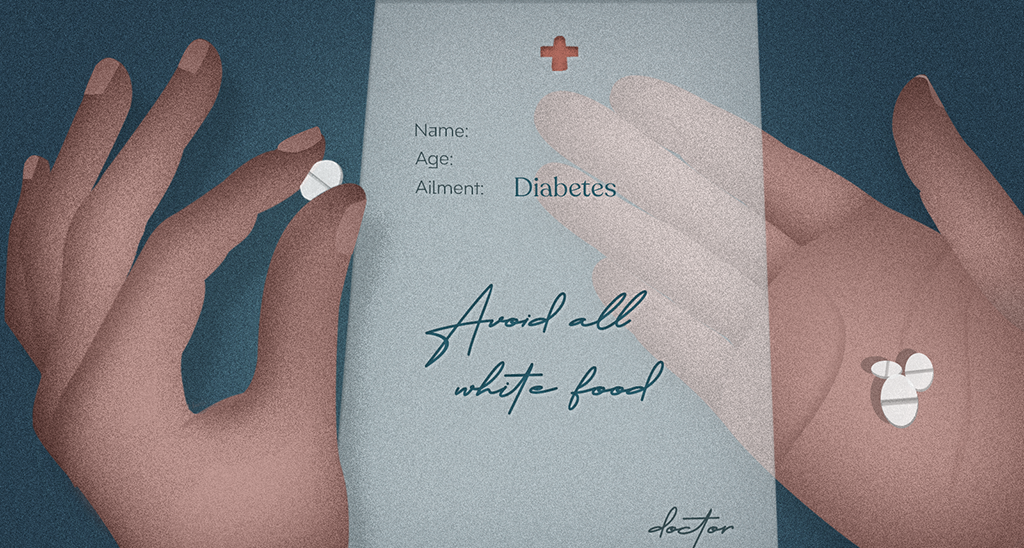

In the south or even Punjab, in public hospitals, there are more check-ups for BP and sugar and cancer so a person reaches the hospital sooner than later. Otherwise a person usually gets his or her sugar check only when they’re really sick. When People Like Us get diabetes, there is someone at home to tell us to check our blood sugar and go to hospital. That doesn’t really happen for people who are poor. I’ve actually seen how people talk to patients in public hospitals. The doctor tells this guy who has been diagnosed of diabetes don’t eat these three things, white things, sugar, something. He rattled it off in three minutes. And what change is the patient going to make to his life with this very complicated disease is a big question.

Why don’t people feel outraged? Why don’t they feel bad about being treated badly? We are supposed to communicate this to people. The idea that you are not supposed to be on your own. You are supposed to get support from the state. Otherwise nothing will change.

What would you say is the sign of a functioning good public health system?

It’s a cliché, but I felt that in Kerala.

As a reporter, I can tell you what the signs are. And it’s just that people are competent.

Because I’ve been working on TB for so long, I have questions that they normally don’t expect, right? It’s not a simple story in my head. I have been down that rabbit hole. In Kerala they had an answer for everything I asked. They just did. Whether it was a state official… they just knew what to do.

And it was not even like they were working beyond five o’clock. Reporting had to end around five pm [laughs]. They knew a lot. In whatever time they were working, they were very, very efficient. They knew exactly what they were doing. They were trying to improve the system. They were trying to innovate in their own way and make things better. And TB is not their biggest worry, but they still want to work on it.

So why do you think it works in Kerala?

I have also been wondering about it. I was talking to someone there while on a story. He said to me, “Kerala women will never have their babies in a PHC.” He was laughing. I asked him why. He said, “They expect better. They will go to a district hospital and deliver [the baby].”

Another remarkable place! Kashmir. Public health really works there. I was shocked at how well it works. In Kashmir, apparently no one goes to a private hospital. There aren’t too many anyway (unlike Kerala which has many). Even well-off people, everyone goes to public hospitals. All their good doctors go to public hospitals. They are well kept, competent. Travel, reaching district hospitals might be hard. And all this a month after [the August 2019] lockdown. It was amazing.

This TB rabbit hole, you talked about. Reporters who have worked through the pandemic obviously will learn things about the country and the state of public health. In a way, they’re learning it in wartime. But from what I’ve understood from reading you, the TB war is ongoing. It’s just that people have forgotten about it. Or are pretending it’s not happening. Is that correct?

Whether it’s TB or malaria. It’s the same.

What did you learn about the public healthcare system from the TB rabbit hole?

You know, one of our biggest problems with TB is drug resistance. It’s something I have been thinking and writing about.

In the system with TB particularly, people used to go to the public health system for treatment. But what it does is this. If you are poor and you have this disease, and you say this medicine is not helping you, they will not believe you. Or if you say you have side effects, they will disregard you. The public health system disregards your own agency.

And that that is a huge problem in TB. What it has done is that it has disbelieved so many patients that it’s actually resulted in people jumping ship and going to random doctors. And that leads to drug resistance.

The system has a very technocratic approach. We’ll do things only a certain way, because this is scientific on paper, but we will not regard what you see or feel. It has penalised patients for not getting better. TB does not have very good cure rate. That’s a major issue. But apart from that, it’s not easy to go to the government system, go there so many times for everything.

It could be something as simple as your TB test being negative. Just like what is happening with Covid. Your tests may be negative. You have persistent symptoms, but they will not check you. That complete disregard of what the person is going through is one of the biggest problems.

Like right now, people are loving getting vaccinated in public health facilities, Like my mother was given chai and all. I am not saying people should get chai biscuit [laughs]. It is just the way in which people are treated because they know you are a more privileged person. That doesn’t seem to happen with TB. You are in a particular rigmarole, a particular machine. You have to come out cured in that particular way. If you have any other problems, then you are screwed. You’re just on your own. Historically with TB our system has penalized patients with this a very technocratic approach.

I feel the second [Covid] wave, people are thinking about it a lot more. In urban areas too people have realised that they are so dependent on the government. That understanding was much clearer in rural India. And for some reason, they’ve tolerated these [poor facilities] for so long.

But people have been expected to take care of their own health for so long that their expectation for the government even now is to stop the crisis, not to do anything for their health in normal times. We are so used to this idea that you are on your own.

Has there been anything that worked in this pandemic? Any element of the pre-existing system?

ASHA workers. In the first wave, and even now for vaccination. An army of people just to do preventive care. Encourage people to take vaccinations, go to hospital when they get ill. That is a remarkable thing. And doing it even when they have not been paid their salaries.

I remember back when they were doing containment zones. When I first heard about I thought, ‘Who is going to go do it?’ I thought about it for a minute and I was like oh damn, the ASHA workers. They don’t even have masks.

ASHA workers always deal with really hard conversations. They are wonderful communicators. They have to handle mobs. They had to do Covid surveys during CAA and all. The police have lathis. These women have nothing. They are just talking to people.

The ASHA worker system originated in Chhattisgarh. Whoever envisioned it as part of the NHM… it’s awesome; that particular part of preventive healthcare works. An army of people who can do this in the community. If only they were treated better.

Read Menaka Rao’s How to Live and Die on the New Dharavi Diet.