As I walked through the city of my hometown,

All I came across was a dominant frown,

A city that had no space to be vulnerable,

made me travel to a far off town.

Getting down at Delhi, a space that marked,

a liberation, a note and a history on queer spaces.

A research to understand,

my role as a designer,

in the city, walking the streets,

led to more questions than answers.

Where can I walk freely? What can I do?

How do I feel safe? What is safety?

The study extended to a larger spectrum,

Is it the space or the people?

How will the city not let me down?

A city gives identity – and anonymity – to its people. But what happens when a city lacks inclusivity? Are all the behaviours and orientations taken into account while designing a city?

Delhi, the country’s capital and a metropolis of great political importance, houses a diversity of spaces and niches for the vulnerable communities. This may surprise us but it’s true. Are these places visible though? Or are they camouflaged and in the shadows?

Delhi has been a landmark site for liberation, too. The decriminalisation of Section 377 by Supreme Court of India in 2018 gave rise to a massive number of people from queer communities owning their true selves. But in reality, removing the criminalisation of consensual acts doesn’t erase the internalised homophobia, transphobia or queerphobia. So where can a person feel or be queer in a physical space? Where can someone feel safe in public, while being their authentic self?

In the middle of the day, when I strolled through the streets of south Delhi, which housed numerous embassies, the streets felt empty and dismal. I felt unsafe, lonely and inferior. The cleaned up alley lined with pardesi boxwood shrubs reeked of superiority. There isn’t a single bench within a kilometre.

While wandering, I sometimes had the impression that the city, like me, craves affection.

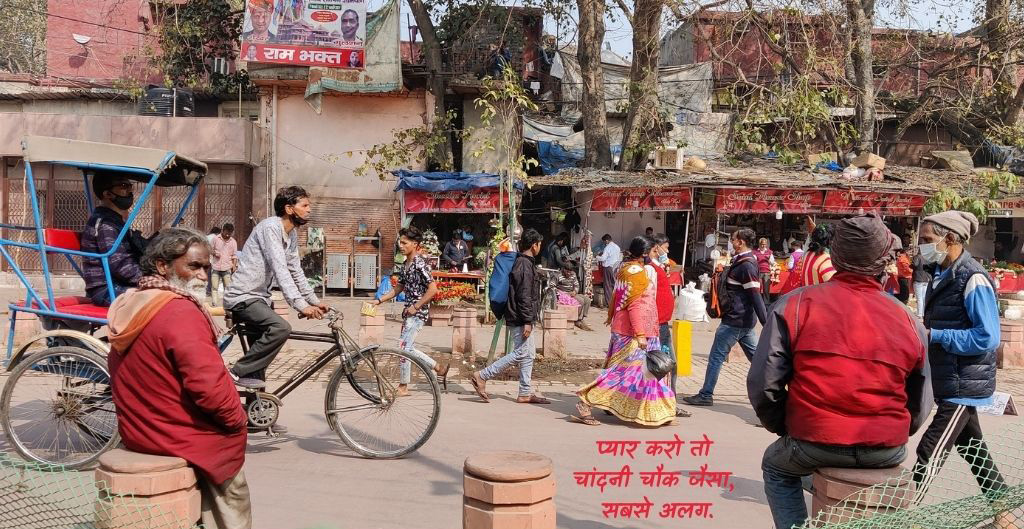

While walking through the streets of Delhi post pandemic, it was revelatory to see that the city intersects and interacts at multiple layers, with a clear contrast of caste, class, gender and politics. I needed a magnifying glass to search for sexual diversity. How can an identity wrapped in fear embody movement in a heteronormative city?

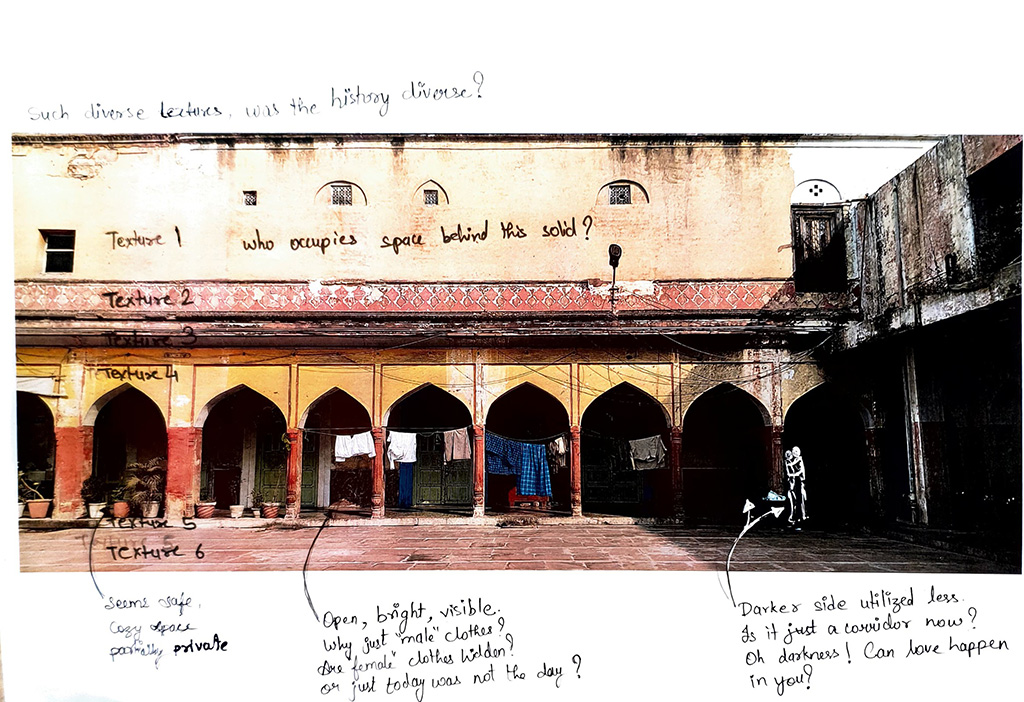

I’ve often wondered why we take certain routes or prefer certain corners in different times of the day. To feel secure at night, I prefer strolling on streets with more vendors and public activity. However, during the day, I prefer to walk in shaded areas to escape traffic, noise and harsh sunlight. These preferences alter, depending on the weather and my emotional state. The dark corners of a building placed in a way that I have an easy access to the lit space, makes me feel safe and calm.

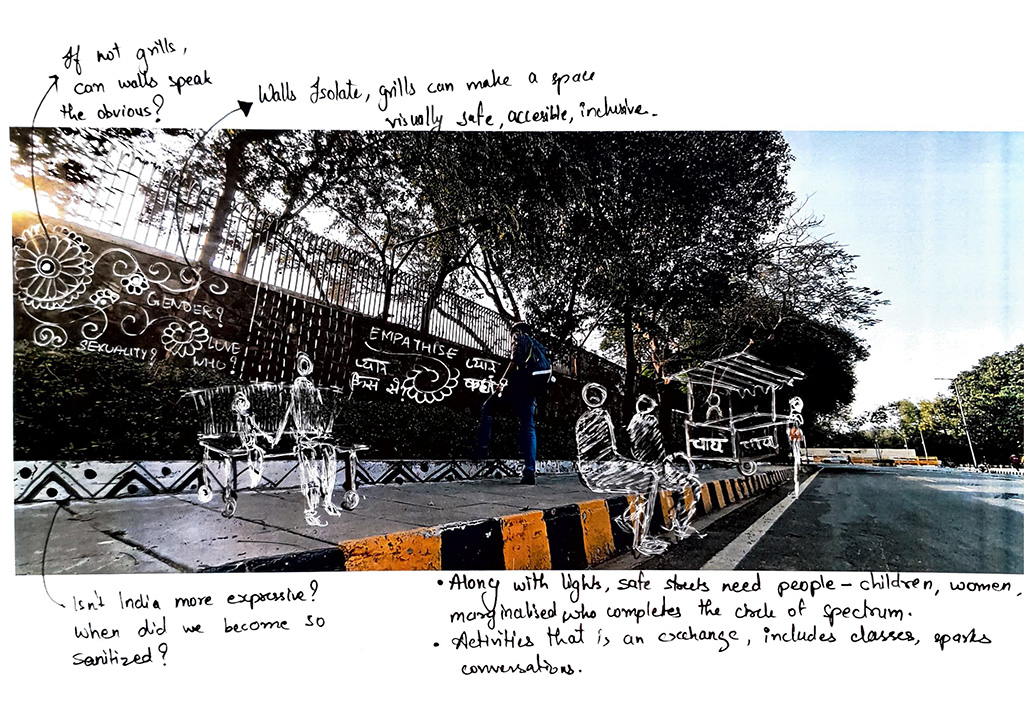

At the same time, when I walked the streets of Delhi at night even though the main roads were flooded with street lights, it felt unsafe and terrifying. As I passed by gated communities, I felt further alienated, knowing the protection afforded was not for me, but from me.

As a passer-by, I felt I was a threat to people living behind these walls.

The compound walls of gated communities included two levels of materials. The lower tier was a thick opaque wall, and the higher tier, which started at my waist, was an iron grill. The concept of a gated community is to create a barrier between the public and private sphere: this half visibility exaceberates the feeling – much like a prison cell. I often wonder, how will people who live inside feel safe when they step out of their sanctuary?

When I noticed cameras everywhere, I became really nervous.

It reminded me of how my parents used to meet as teenage lovers in gardens, temples, and numerous other locations across the city, wherever they could find privacy. Just like in their generation, they felt love marriage was a fragile achievement, today, I feel same sex love is extremely vulnerable. Just the way anybody can send you unwanted DMs on Instagram, anyone can find you in a metropolis. The concept of privacy has evolved into a very class-based and hierarchical one.

But the scale and density of Delhi does mean you are both known and unknown at the same time.

The very famous queer hangouts like the Mykonos Spa and Q Café in Delhi closed down due to the pandemic generated economic instability. Heteronormative spaces continue to survive the worst.

The few other queer-friendly spaces that survived and came back to life post lockdown, showed a hike in their prices and ultimately became exclusive for people like me.

But Delhi has people that build and encourage relationships between space and sexuality – the affectionate city. There are NGOs who organizes picnics, events and gatherings, facilitate pro bono or affordable mental health therapy for LGBTQIA+ individuals, help make spaces more inclusive, build communities and bring organisational support to queer lives. Few other Indian cities have that.

The streets of Delhi are surprising at many points. Even in a short walk, you can come across wall art, a political quote sprayed over some older quote, historic abandoned architecture, diversity of flora and a variety of birds.

A space that intrigued me the most was Sunder Nursery. As we enter the nursery, the panoramic grandeur and openness of the space is revelatory. As we walk on the paved way, there was an arrangement of flower beds that were all different from each other.

Another remarkable feeling was the unpredictable nature of this garden. I think this layered, diverse and uncertain nature of a garden at various stages of life, reminded me of how my life unfolds in front of me today.

While I experienced Delhi for days as an outsider, a visitor, with a particular lens, the favour was returned to me. While I was in the train back to my hometown of Vadodara, I got a glimpse of how Gujarat maybe perceived by Delhites. As I was lying down on my berth, two men were on the berths opposite me and I could not help eavesdropping. One of the guys said, “Mein Ahmedabad pehli baar ja raha hu, tum gaye ho? (I’m going to Ahemdabad for the first time. Have you been before?).” The other guy folded his legs on the berth gave a sad look and leaning towards him said, “Hum jahan ja rahe hai na, wahan garmiyo mein shole baraste hai (Where I am going, fire rains down the skies in summer).”