This article discusses the development of social work professionals who are trained for work with prisoners. It traces milestones that seem to need crossing, in order to work with a population about whom existing narratives can become smokescreens. Social work with prisoners cannot take place unless there is a re-examination of the narratives that students carry.

Prisons are taken for granted within ‘civilised’ societies; we often do not think of the what and why of the institution. Often, we find ourselves at one of three points on a continuum: being oblivious and uninterested, feeling secure in knowing that there is a prison, or being concerned about the people who reach prison.

Against this backdrop, there are several professionals who choose to engage – both with and within the criminal justice system. They take on the roles of investigating, arresting, prosecuting, representing, providing justice, and playing custodian as they take prisoners through their sentences. However, amidst all this, what remains lacking is a category of professionals who focus on the psycho-social determinants of crime and the processes of re-entry and reintegration after prison.

Social workers are a group of professionals who have a valuable contribution to make in this regard. However, the appreciation and institutionalisation of this role as an essential one in criminal justice, is yet to take clearer form and shape.

Recognising this, in 1954 the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai started offering a Master’s programme in Social Work, with a specialisation in Criminology and Correctional Administration. It was open only to functionaries of the prison administration till 1970, but was made available to members of the public thereafter. It has therefore been only a little over 50 years since social workers in India have begun training in criminology and prison-based social work.

However, the prison system remains a conventionally and largely closed space; prisoners can rarely be accessed by social workers that were not recruited by the system.

It was between 1985 and 1990 that Dr. Sanober Sahni, a lecturer with the department of Criminology and Correctional Administration at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, entered and engaged with the prison system in an effort to emphasise the role of trained social workers in the correctional process. Over the last three decades, Dr Sahni’s brainchild, Prayas*, a field action project of the Centre for Criminology and Justice, has been active in making social work intervention available to women and young adult prisoners in Maharashtra and Gujarat.

The Tata Institute of Social Sciences, through their postgraduate degree in Social Work with Criminology and Justice, continues to train social workers for intervention within the criminal justice system, with a considerable focus on prison. Needless to say, working within the closed prison system and all that it holds behind its bars requires conviction, commitment to the cause, and the ability to defend a prisoner’s right to service and rehabilitation in an environment that often believes otherwise.

The social worker in prison is, more often than not, a member of the voluntary sector and is rarely on the rolls of the prison staff**. She/he holds no formal authority, and visits prison as part of an effort towards taking social work services to prisoners – a group that is seen as marginalised, vulnerable, and often excluded from the frame of social work. This kind of social work recognises a prisoner’s disconnect from community, the stigma that exists therein, and facilitates the delivery of services such as legal information, legal aid, contact with family, services towards children, and interventions related to other systemic issues.

In social work, the person is a primary point of focus, but not without the socio-political and cultural milieu they exist in. Forming relationships is the agreed upon starting point for most prison social workers.

The social worker has to first move past the identity of ‘accused’, ‘offender’, ‘prisoner’, ‘criminal’, or ‘convict’ to the person behind the assigned identity.

The social worker cannot engage optimally with the time spent in confinement, without an understanding of how the pre-custodial history has influenced the person in custody, and in turn, how this history will influence the person who will be released back into the community at the end of a prison sentence.

The social worker thus needs to accept the person that is rejected, establish a relationship of trust within an environment of mistrust, and believe that a person can move past actions and patterns of behaviour that have caused harm – even when society, the system, and often the person themselves do not believe that it might be possible.

The above goals are met through the indispensable two-pronged pedagogy that enables the experiential integration of theory and practice, which social work adopts. Through this pedagogy, classroom teaching is coupled with a component called ‘fieldwork’, which is a guided and graded process of experiential learning. Hereby, a student of social work is placed within a live and functioning system, and learns about the realities of people and the practice of social work. For students who have chosen Social Work in Criminology and Justice, doing fieldwork in prison is an option. While prison is chosen by students who feel inclined to work with prisoners, their starting point inevitably becomes a process of cutting through and countering dominant narratives about prisons and prisoners that we all imbibe by virtue of being a part of the mainstream.

I write as a fieldwork supervisor who has walked this path myself, and now accompany and guide social work students on their respective journeys. Over the years, as students proceed through fieldwork, there are beliefs related to prison and prisoners that emerge. As students engage with these positions, one can see their beliefs shift, and new dimensions open up. I am going to refer to the beliefs students originally carry as the dominant narrative, since they reflect the majoritarian position. Then, we examine how we set out to challenge them as educators.

1. The prison as an institution and the nature of prisoners: As a student starts training to be a social worker in prison, this is probably one of the first elements of the narrative that starts getting challenged. Students have notions that are largely conceived from the media about prisons being dark and dreary, and about prisoners being rough, tough, and dangerous.

When students first enter prison, while the living conditions may not be the best, they do not align completely with what the student expects. The student and the social worker that they accompany, are approached by the inmates. Students meet people who are accused of or convicted for theft, cheating, murder, trafficking of people or drugs and a range of other offences. Students often experience an overwhelming mix of emotion as they realise that the images that they carried into prison were conjectures based on dominant narratives about people who commit crime. The face-to-face meeting with a person who has allegedly committed a crime often serves to break down faulty inferences, and forces the realisation that there is a person and a set of circumstances behind every crime — a fact that often eludes us until we come in direct contact with a prisoner.

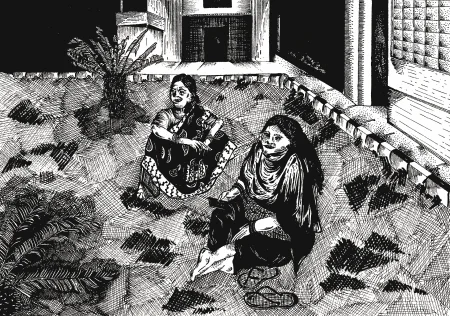

The situation of women in crime also gets concealed within the dominant narrative. Women are generally seen as victims and rarely as offenders or aggressors.

The idea of women committing crime is often sensationalised because of the interest and attention it generates. It draws much moral judgement and is considered more unacceptable than men committing crime. This can be seen in the extent of the social and familial distancing that often happens to a woman who has been accused or convicted of a criminal offence.

Issues related to lack of opportunities for education, early marriages, violence and abuse, responsibility for children and economic dependence are not highlighted.

However, in the course of engaging and intervening with women in prison, students can see that most women in prison have histories of mental, physical or sexual abuse; they belong to weaker socio-economic classes, have low levels of education, are financially dependent, have experienced gender-based discrimination and are ignorant about legal processes.

2. Prisoners as a homogenous group: Prisoners are often seen as a homogenous group. There is very little understanding about the variations in their contexts. An understanding about prisoners is influenced by the distance that exists – between them and the people who create the narrative. Hence, while from a distance prisoners may seem like a homogeneous group of deviants, as students come closer, the dimensions and details become more visible. Students realise that people in prison cannot be categorised under a common label, and begin to notice the many sub-groups that exist in prison.

Gender becomes a starting point of categorisation. The charges against different inmates go on to become another level of differentiation where offences range from petty to serious. In addition, there are those who have come into prison for the first time and those who have repeat arrests, there are the young and the old, those who are a part of families and those who are not, those whose families support them and those whose families have proceeded against or disconnected from them. There are prisoners with histories of homelessness, substance abuse and mental illness. There are those who have become a part of organised crime networks and others who may be on their own. There are those who approach the social worker and those who do not. As students engage, these variations in contexts become visible in a manner unlike before, and there is realisation about the existence of a larger collage when it comes to the idea of prisoners. Students also start realising that these factors too play a role in the individual’s susceptibility to crime and the subsequent outcomes of re-offending or rehabilitation.

3. Who deserves to be helped: The dominant narrative is that prisoners are people who have victimised other people and are solely responsible for the harm that they have caused. It is therefore an accepted position that they do not deserve help. If prisoners are to be provided a service, there needs to be a reason that makes them deserving of it. For students entering prison, there is almost an inadvertent tendency to try to seek out those who seem to deserve help for being framed or falsely implicated.

It appears that the dominant narrative induces a sense of guilt among students about providing a service to someone who has harmed another.

Over the course of fieldwork, the student starts to understand that the pathways into prison have been influenced by many factors, many of which are social and structural in nature. The social worker’s role is to understand these experiences and work with the prisoner towards finding pathways back into society. The student also begins to understand that everyone who reaches prison – whether falsely implicated or not – needs to be worked with, because the fact that they are in prison is an indication of their susceptibility to arrest and crime.

Furthermore, if innocence was the criteria for receiving service from a social worker, the relationship will become amenable to manipulation, which will then defeat the purpose of the social worker’s entry into prison.

4. A blanket denial of contact with prisoners accused or convicted of crimes that are considered as heinous: Certain crime forms are socially perceived as heinous and more unacceptable than the others. Student social workers coming to prison carry the same perceptions, and not unexpectedly so. Murder, dowry deaths, drug and human trafficking, rape, kidnapping, et cetera are words and crimes that create unease and generate strong emotions.

Students go through dilemmas about how a woman student should respond to crimes against women.

For students learning about social work in prison, this becomes a journey of reflection about the role of the professional, with questions related to whether a social worker can stop at the crime label and refuse to look at the person behind it. This is often the time to deepen understanding and recognition of the social processes that have played a role, and to think of an appropriate response.

5. Images of prison staff: Prisons are seen as imposing closed institutions with a retributive purpose. The prison staff is often perceived as a group of personnel who execute the retributive functions through inhumane and disciplinary action against prisoners. While these images and impressions start getting revised following a student’s entry into prison, establishing contact and communication with the prison personnel takes more time. Nonetheless, over time, students learn that beyond a sometimes-intimidating frame and unapproachable demeanor, the prison administration personnel have opinions and positions on prisoners and their treatment, ranging from retribution on one hand, to a recognition of the prisoner as vulnerable on the other.

Students witness prison guards and officers being moved upon seeing emotional moments between mothers and their children, or when there are visibly difficult circumstances that an inmate might be facing.

This enables students to move from a predisposition for seeing prison personnel as rigid and authoritarian, to understanding that the institution performs a certain socially assigned function and its staff has to adhere to a role. Moreover, prison personnel are also positioned varyingly and cannot be seen only as oppressors. Students also start understanding the complexities in the work of prison personnel, and how it impacts them and their lives.

6. Rehabilitation as rhetoric: Rehabilitation is a term used for a multiplicity of groups and responses, and may mean many things, depending on the context. When it comes to prisoners, rehabilitation seems to be understood more as rhetoric, and is perceived as simply providing training or employment. Students carry the same simplicity in their understanding of rehabilitation. During their fieldwork in prison, students start learning that in order for rehabilitation to happen there are many obstacles to be crossed on the way. Students begin to understand that rehabilitation is a complex process; if someone has got into crime and acquired certain behaviour patterns, it takes time to retrain behaviour, redefine one’s roles and the imbibed labels, acquire new skills and relationships, and settle into a new livelihood and lifestyle. Considerations around whether the prisoner will return to the pre-prison location, how strong or weak the prisoner’s social support is, what the risks for exploitation or re-offending are, become a starting point. Rehabilitation also cannot be a time-bound process as it is often understood, and a long-term engagement with the prisoner is necessary as there are many layers of experience and trauma that have to be worked through.

7. Acknowledging the victims in the crime: The dominant narrative is one that sees ‘criminals’ and ‘victims’ as two mutually exclusive categories. Students often start their fieldwork with a similar position. Through the fieldwork journey, students begin noticing the overlaps and the histories of victimisation in the lives of prisoners. In the course of fieldwork, they may also have the opportunity to meet someone who is a victim of the crime (for example, in one case, a woman and her son were in prison for the murder of her husband. The woman had asked to contact her adult daughter. The daughter, while being the child of the accused was also the family of the deceased and was a crime affected person/ victim in this case) for which a prisoner is in prison. While ordinarily it may seem natural to position oneself against the offender, the student learns to recognise areas of need, irrespective of whether they are related to the prisoner or the victim. They learn to make referrals, maintain emotional balance, and perform a professional role based on a deepened and more scientific understanding about crime and victimisation based on real life experiences. This is undoubtedly challenging as it calls for a reflection, re-examination, analysis, and an eventual re-positioning of one’s beliefs.

Students invariably develop the understanding that victims and offenders are not exclusive categories, and that crime has its roots in the social structures that promote and sustain inequality, rather than in the individual who may have perpetrated the crime.

In two instances, students had an earlier exposure to working with women who had been subjected to domestic violence and human trafficking, but while doing fieldwork in prison, the students met women who were accused of dowry-related deaths and human trafficking. While engaging with women who were on the other side of the offence was challenging, it also helped the students develop an understanding about the cycle of violence, as the accused women had also been subjects of gender-based socialisation, discrimination and violence at earlier points in their lives.

Social work is located within and guided by the values of social justice. However, despite this, groups of people such as prisoners are still often excluded from the realm of social work and other services, because of the contention that surrounds them. Nonetheless, it is imperative to recognise that these groups of people are also products of social processes, structures and stratification. Students who opt to learn about social work in prison may be taking a first step towards reaching people and issues that may have stayed unreachable due to the inherent complexities and dilemmas of working with them. Students have opportunities to come in contact with people in prison, engage with the families of prisoners and criminal justice functionaries, follow and understand procedures, learn about the criminal justice system and see the impact of criminal justice processing and incarceration. In this process, students begin to recognise the prevalence of dominant narratives and their role in shaping the understanding about prison and prisoners. The learning is intense with experience, emotion, introspection, reflection, and repositioning, and it takes social work with prisoners a step closer towards its goal.

Read in Hindi.

* Prayas, a field action project of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences has been endeavouring towards the creation of posts for social workers within the criminal justice system through demonstrating scope for direct social work intervention, offering mentoring programmes, and is currently in a MOU with the government of Maharashtra where social workers have been taken on in five central prisons across the state.

** According to the Prison Statistics India reports (published by the National Crime Records Bureau, Government of India), prisons in India have a category called correctional staff which comprise probation officers, welfare officers, psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and others enlisted in the given sequence. The most recent publication of the Prison Statistics India report (2022) says that there were 820 correctional staff posted across 1,330 prisons in the country as of 31st December, 2022. Out of the 36 states and union territories, 16 states and union territories had no correctional staff. 4 states had only 1 correctional staff, and 1 state had 2 correctional staff.