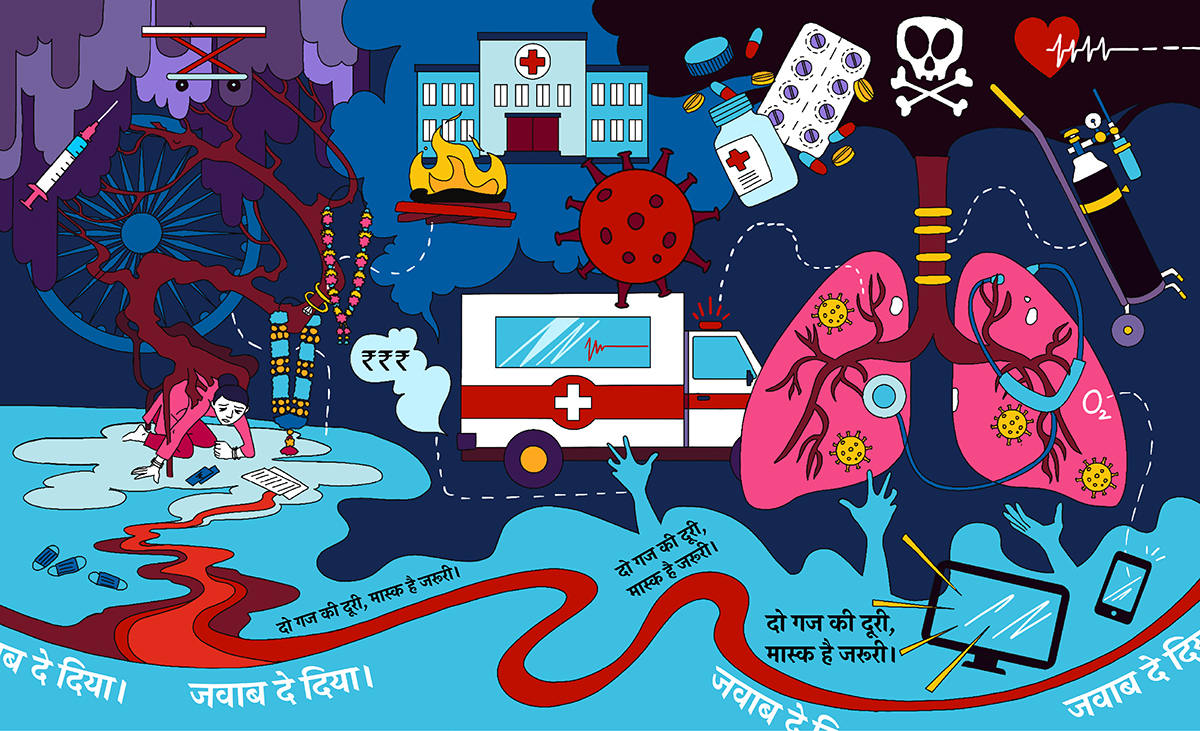

In response, or maybe a rejoinder, to urban conversations full of lament – “Why don’t they just get vaccinated? Why are they getting married at this time? Will they ever learn?” – Disha and Kavita of Khabar Lahariya, after decades in rural Bundelkhand, come with a rather gentle reply (all things considered).

Ideas of cities are shaped by the rural-urban continuum, and some questions slide equally across cities to towns to villages: what is rural UP’s relationship with death? What is a rural Indian citizen’s appetite for risk, and how has this appetite been fed, structurally and systematically? What does life mean when its value would not fill a MGNREGA receipt? Who is there for us, when all fails? Would making new kinships – through marriage – help us survive a pandemic?

As part of The Third Eye’s journey – from its Public Health to its City edition – we bring you a love letter from rural Bundelkhand as love letters used to be: searing and blood soaked, with a call to arms.

One day in the peak of the second wave of our Covid-19 pandemic, we were reminiscing with an old, fully vaccinated, Ambedkarite farmer we know in UP, about the other mahamaris he remembers seeing or hearing about, that remind him of the present one, if at all. You know, the public fleeing and forced isolation and government-targeted surveillance and treatments. Of course there were others, he said (bigger, better, he seemed to imply), that destroyed and petrified entire villages. Motijhara, or typhoid, which never really went away, in which sometimes the heat in your body caused tiny, shiny boils to form. Tuberculosis, the magnificently named raj rog. The plague he remembers, hearing stories as a young boy, or tijari or chauthiya, because you died on the fourth day of contraction. People retreated to the forests as it spread. And chechak, or smallpox, that marred your limbs and scarred your face. His sister-in-law got it, and was finally married along with her healthy sister in a two-for-the-price-of-one deal. (Marriage is a great redeemer.) She later fell sick again, with typhoid and jaundice, and died in a hospital on a ventilator.

Now, stepping over bodies has become so routine that we are hardened to the slower drama of an epidemic. We see more bodies in the morgue because of development and roads and highways and overcrowded buses and tempos and gravel on the roads and helmet-less bravado.

Mar hi toh gaye hain, na? It’s only death, isn’t it?

Uttar Pradesh, July 2021.

We are now Covid-mukt, in Chitrakoot, in Mahoba, and 44 other districts of Uttar Pradesh. And on Facebook, as per promotional, mutual back-scratching posts of district magistrates and local journalists. What will change from when we weren’t Covid-mukt? We were going to the gym with the shutters down anyway; they started allowing regulars and influencers in the heat of Coronakaal, when it was getting a little suffocating to not go out. Typhoid cases seem to have increased exponentially, and strangely, more critical cases of typhoid than we ever knew. People are even dying of typhoid like they did in the old days. But not much else is new. Dikhitwara in Naraini saw 25 deaths between the April 25 and May 15, 2021. People ran a fever, had coughs and colds, and debilitating weakness. Only one tested positive for Covid. This was revealed when deaths had come and gone, when unreliable residents said they had lost not one, but two or three people per household, and a reporter stumbled on their empty houses. The local health official said the reports of deaths are greatly exaggerated; there were only 11, and three or four of them were very old people who had heart conditions or asthma. In any case, high-level officials were dispatched to Dikhitwara. This isn’t about Covid, this is development, or politics, depending how you look at it. Entire villages get sick and either get better, or don’t. A few people die. The district sends a team to investigate, sets up camps where unreliable residents are asked peremptorily about symptoms and personal hygiene, sewers are hastily cleaned, medication kits distributed and tests done, the results of which are often unknown. Too much, too late.

Meanwhile, the unreliable residents of Dikhitwara weren’t interested in taking medicines that don’t seem to work, or going to the Community Health Centre in Naraini to report on their wellbeing, getting admitted in a district hospital from which you will not return, or getting another dose of the vaccination that can lay you in bed for weeks or possibly kill you.

This is how development and primary healthcare works. It’s humiliation and negligence and money and misplaced intentions and trust and we’re better off without you, thank you very much.

Chitrakoot, June 2021.

A plump-cheeked infant, three months old, apple of her parents’ and grandparents’ eyes, contracts a cough. No big deal. Everyone in these parts has a cough through some or most of their life. It’s usually because the weather has changed, or something inappropriate has been eaten. And Shreya is so black of eye and pink of cheek! The cough persists, for days, weeks, it’s hard to remember. Soon, her whole body rattles, like the toy she doesn’t own, when she coughs. Her whole, plump, healthy body. And she finds it hard to breathe. Her mother takes her to a private doctor in the district headquarters where she is given some medicine to dispel the symptoms. Neither mother nor grandmother nor doting friends know the cause for Shreya’s constant cough. Dava ho rahi hai. Four days later, around 9 pm, her black eyes are widened and still, and she isn’t breathing anymore. She is torn out of her screaming mother’s arms and taken from one private doctor to another, and then the government hospital. They all refuse to see or admit her. Jawab de diya, we hear, whispered, whether in spite of, or because they haven’t seen her or admitted her, we don’t know.

After four – maybe five – refusals, a kind compounder, only partly awake, in a government hospital takes her in, and tries to pump her already dead body with oxygen. Thinking back, what kindness.

Is that how Shreya’s mother was able to let go of grief, let it settle in a non-intrusive part of her body, her doting grandparents never accusatory or incensed at the circumstances of this loss, enabling Shreya’s mother to heal, be back on her feet weeks later, back at work, insistent that life goes on?

In watching how the system meant to safeguard your life and that of your loved ones fails you, this was a lesson in understanding one’s place in the universe. And when we say one’s, we mean a Dalit woman in the most populous state in the country. This year, UP means to spend 6.3% of its budget on health, more than the 5.5% average of other states, but less than what it means to spend on roads and bridges. What does that mean for the Dalit woman and her baby, whom the system turned away?

Voices from Grassroots Women’ Collectives in Bihar recall their brush with public health. Swasthya se yaad aaya…

How do you engage with the anticipation of death?

With anger? Or faith? Or resignation?

Or pragmatism? That life and death are part of the same spectrum, and your chances hinge on the roll of the dice?

Is this a choice we make, or are these made for us?

Does your dealing with death have to do with who and where you are? Whether in a city packed with glass-fronted new hospitals, or a village with a malfunctioning primary health care centre?

Or is it determined by an inheritance of the value of your life: paltry, or exaggerated?

Ontological arguments, global pandemics and public healthcare infrastructure notwithstanding, we’d stake a claim for an alternative perception of the value of life, or the significance of death, than what we have at present.

Chitrakoot, Allahabad, April 2021.

Shanti’s father was with the police, that most coveted of jobs, and yet her mother died of the coronavirus.

She wept as she told the story.

(Tears play a big role in marking and healing from occasions that change us, anger us, sadden us, leave us maimed: we weep like our life and death and rebirth depend on it.)

Shanti’s father was posted to West Bengal on election duty and her mother was besides herself with fear. A little while before, he had been posted in Chhattisgarh, and there was an encounter where scores of policemen were killed – most of whom were from UP. Shanti’s mother watched the news, distraught. She kept calling her husband’s phone and there was no answer. Finally, a video call from him calmed her heart. But Bengal was full of black magic, she said, who knew what they would do to him there. She stayed up all night in fear. She stopped eating. One night, she woke with terrible body ache and was taken, by force, by Shanti and her uncle to the hospital. She was there for many days, and kept getting worse. She was unable to breathe, and a CT scan showed infection in her lungs. The hospital discharged her. Jawab de diya.

Shanti took her mother to the district hospital in their own vehicle, but there were no beds there. From there, they tried to take her to the Banda Medical College which had prepared facilities for Covid patients from last year, but there was no oxygen available there either, and Shanti’s mother desperately needed oxygen. Someone suggested – JP Memorial Hospital in forested Shankargarh, Allahabad, and they managed to get a bed there. In two days, when her condition continued to deteriorate, and oxygen, medicines and even doctors became unavailable, she was referred to Kanpur or Allahabad’s district hospital. No ambulances or beds were available. For four days, Shanti’s mother kept asking if an ambulance was going to come to take her to a place that would make her better. Shanti kept saying it’s on its way. Shanti’s husband found an ambulance driver who agreed to take her to Kanpur, if the amount – 50,000 rupees – would be Google paid in advance. It would include two oxygen cylinders, a doctor on board and a bed with a ventilator in a Kanpur hospital. They negotiated it down to Rs.30,000. As soon as the amount was transferred, fthe ambulance broke down and the driver switched off his phone.

Shanti’s mother died, with her family and the medical staff watching, unable to do anything.

In Gobrigodampur, 60 km from the Banda Medical College, the air is clean; there’s clear water in the streams; and there is no electricity or television. This village, surrounded by forest and low hills, falling between UP and MP, home to Thokia, a much loved and feared dacoit, has a history of erratic ration distribution, sporadic schooling, few health workers visiting for check-ups of any kind, or vaccinations till a few years ago. Development gaps notwithstanding, no one fell prey to the coronavirus here.

Grameen mahaul shant hai. Where there’s no hauwa, there’s no corona.

You see, it’s the television that steals your sleep and immunity. The more you watch the news, the less you sleep peacefully, the more your body hurts and your breath is laboured.

Four kilometres from there, in Bhagolan, slightly less remote and only slightly more important than Gobrigodampur, there was a fever in every family a few weeks ago. It happens every year, said inhabitants, seasonal flu. The difference this year was that everyone got sick, not just one or two. There was no one there to cook, to make tea, to give you water. Then they chuckled. This year, they said, we got medicines thanks to the panchayat election campaigns. They did camps, health check-ups! We didn’t need to go to the health centre – there are no medicines there anyway. And we’ve heard they may give you an injection that kills you if you go! We’re fine now.

Last year, when this coronavirus broke out, we chuckled a little as well, at having Amitabh Bachchan’s sore throat captured in our phones; and how this kind of awareness campaign could have finally dealt with the tuberculosis in almost every household in some parts of Bundelkhand.

Our digital educators went around in their mohallas in UP and Rajasthan to see what people remember and learn through country-wide PSAs.

This year – it is the air that is killing people, the virus hanging in it, the lack of oxygen in our hospitals.

What next? Water?

The things we take for granted, the only things.

Well, not the only things. Thank goodness for political one-upmanship, we say, thank goodness for Nasimuddin Sidiqqui and his completion of the Banda Medical College. Where would we be without the Covid ward at the medical college – our version of the glass-fronted shrine to the Corona Goddess? We wouldn’t know half the things we do now. Isolation and RT/PCR. The principal of this medical college locks the ward at his own discretion, especially when there are too many patients or when the number of patients in a day goes above what is permitted, to test and to admit as per the district administration directive, and the state administration above them. The distance between a patient with a medical emergency and a patient you give up on – jawab de dena – is minute, unpredictable, ambiguous.

The electricity department in Banda district saw seven employees die of Covid through May. The list of those dead does not include the source of the infection, who continued to come to work after having tested positive and didn’t stop even when many colleagues had died.

Mahesh, the driver on duty at the electricity department, was dispatched, while the rest of his department mourned, to be part of a baraat, since whatever happens, marriages will continue in Coronakaal, darubaazi will continue, you have to mark your presence, you have to stay part of the community. Else who will cremate you when you go? No one wants to die alone in a hospital. So ritual is important, social capital is important, maintaining networks is important. If the path to protection from a new virus (which adds to all the other ways we may or may not die) is isolation, then forget it, we choose community. There are things that make life less tolerable than a fever.

(Also, this is a good time for weddings. They’re cheaper, guest lists are limited, DJs and orchestras are banned. Inflation is at a record high, vegetables and oil are selling at a premium and so you make do with shopping once in 10 days, and feed your children chutney and roti meanwhile.

Anyway, weddings are cheap, as cheap as life, as cheap as death, so it’s as good a time as any to settle your children down. The number of old people dying, who knows who will be around next year?)

This year, our state government threatened to disallow candidates with over two children to contest panchayat elections, in line with an ongoing effort to control population by limiting access to democratic entitlements. Slow death.

Because, poor development and governance could only be the fault of the proliferation of the rural masses. With Covid, Yogiji has been handed a good way of controlling our population.

Chitrakoot, Satna, Jabalpur, May 2021.

On the night of the May 5, Lakshmi, weak with dengue (the only test she agreed to do), heard that her father-in-law had died. The family was quickly told to showing up, wherever they were. No one could think of refusing in these circumstances, whatever qualms they would have had from watching too much television. Lakshmi was, at the time, at her parents’ home in Chitrakoot, where she had been for a few months, after an argument with her in-laws over having bought a piece of land in her own name. Lakshmi was a government schoolteacher, and played an important role in supporting her in-laws’ family. In any case, this bit of gumption – buying land in her own name! – was a bit much for her father-in-law, while her husband being wanting of spine, said little in the matter. Lakshmi left.

Death galvanises unlike any other moment, and so the moment she got the call, her sister got hold of a vehicle, went to Manikpur to get Lakshmi’s husband and uncle-in-law. On the way, with a pulse that could have done with an oximeter if the local pharmacist had any, she heard the facts of the case. Lakshmi’s father-in-law had died in the Jabalpur Railway Hospital. He had tested positive for Covid a few weeks earlier. Falling sick after his first vaccination, he had been taken to Satna, to the government hospital. He worked for the Railways, and his brother was a contracted employee in the Satna District Hospital. So access to a bed and doctors was not an issue. He received good care, but his condition steadily deteriorated. On the night of May 2, the hospital had a shortage of oxygen and Lakshmi’s father-in law-was one of the Covid patients whose condition plummeted as a result. He was referred to the Railways Hospital in Jabalpur, where a ventilator was available. He died just as he was being taken to the ventilator bed.

Lakshmi’s sister tried to keep her mind on the tragic facts and away from the realisation that she was in a car full of either Covid-positive people, or those highly exposed.

En route to Jabalpur, and by now part of an entourage, Lakshmi’s sister received a message that the body was returning to home to Manikpur, and that the last test of the deceased had, in fact, been Covid-negative. Lakshmi’s husband got on the phone and called everyone he knew to come and pay their last respects. In the dead of night, on the highway from Jabalpur to Satna, the body was divested of its sealed wrapping and PPE, and dressed in a respectable white cloth for its journey home. Lakshmi’s sister swallowed her doubts about the powerful and their medical records and followed the funeral entourage.

By the time the mourners returned to Lakshmi’s in-laws’ home in Manikpur, the town, small, bordering UP and MP and home to the region’s finest dacoits, was teeming with relatives and neighbours. The cremation happened with first light the next day, and was thickly attended.

The recently Covid-positive body was at the centre of much physical and emotional attention. Sab ne laash ko pakad pakad, chipak chipak kar khoob roya. Six hours later, in the now-burning mid-day, after everyone had loudly and proudly performed their grief – including the party-conscious, dengue-afflicted daughter-in-law, the possibly Covid-afflicted son and wife (they won’t test, because testing leads to hospitalisation and in hospital you die), all feuds forgotten for the time being – the body was cremated with due fanfare.

We’ll never know as many people with Covid as with tuberculosis. TB sucks the life out of you slowly. It’s not dramatic, it’s a lot of wheezing and coughing and tablets for years and years that seem to be doing nothing.

Especially if you can’t afford the milk and fruit and eggs that are meant to support the treatment. In UP, we can proudly say, we have the highest rates of infections, the slowest decline rates, and the worst records of complying with the recommendations of our TB programme that mandates cash transfers for food for patients. Without nutritious food the treatment is unlikely to work and TB makes you feel so utterly depleted that you cannot go on – even if you’re told that you’re an unreliable, ungrateful illiterate dehati for stopping free treatment. Yes, that’s all the state will tell you; not that they are ashamed of how many of their people suffer from a disease that is now only material for literature in most countries. And definitely not the ravages that the drugs will bring upon your bony, frail body; that the treatment may make you more ill than you ever felt before. They will not divulge that government doctors dealing with primary health care spend less than two minutes per patient on average — even for a disease that requires mammoth patience and counseling support. Or that, even if this is now a commonplace acceptance, the terms and conditions for accessing the free DOTS treatment, are so humiliating and logistically absurd: you have to come back to take your pills under observation every day or every other day for months and months on end, because the state doesn’t trust you will take them on your own, given your unreliability.

If you don’t die of TB, you’re definitely going to die of medical debt, accumulated from years of inability to work. But that’s still fairly undramatic.

In the past 20 years, we’ve only seen cases of TB increase: 3 million cases reported, 350,000 people die each year, higher than the current COVID toll.

It has been, and is still, an epidemic that just doesn’t go away. If the data disagrees, and claims a decline, from 2500 to perhaps 2000 cases per day, we don’t know what this means, given we’ve seen more cases unreported than reported. And empty TB registers in the homes of health workers, because, honestly, how many things will an ASHA worker do? Apparently, we will be TB-mukt in 2025, five years sooner than the 2030 target as per our sustainable development goals commitment. (UP has not been one of the states that has signed on to this target.)

The apparent national capture of ‘missing’ cases notwithstanding, we have found a swathe of cases in a remote village, off the health workers’ map, where a member of each household had a cough trapped in their bony chest. We have found cases in kasbahs where widows survive on unpredictable, Rs.1500 a month pensions, eventually hollowed out from the disease, and sons who can’t be bothered to take care of them on a long-term basis. Sometimes we find them in smart, upwardly mobile, Dalit families with prospects – prospects that hinge on keeping the fact of a rattling chest and a previous TB diagnosis a secret. And we’ve found cases in villages surrounding quarries that have been mined hollow; and in villages where quarrying was suddenly stopped and now there’s no work, shocking poverty, and only the dust that keeps TB coming. There are almost always fewer people to talk to when we go back to visit. Ek aur maut. It’s a quiet, undramatic control of unimportant populations, the ones that don’t make it to the register of national anger.

If you try and stick a poison needle into us without our consent, telling us it will prevent a disease that we’re unlikely to die of, while having failed over decades to eradicate a disease that has, and will continue to, kill generations of our families, we will voice anger that has been on slow boil. And don’t tell us it is ignorance.

The relief workers during one of their field visits for ration distribution encountered a situation where the family confused ration with vaccine shots and ran off to the fields. The video was taken by Mithilesh, one of the relief workers in Lalitpur, UP during June, 2021.

A friend tells of hearing from Adivasi colleagues of a fever similar to this one, 300 years ago, in a forest in the south of the country. It was called benki jwara, or the fire fever. The medicine men and women of this forest are brewing a secret potion to cure it, which they will not be sharing with the rest of the world. In the meanwhile, they have got their first vaccination and await their second, and spend lockdown days experimenting with compost pits and cow urine-fortified slurry.

Death and disease will come and go, there’s little we can do about it, except hold fast to the things that matter.

(This story has been enriched by conversations with Madhav Prasad, Manjot Kaur, Avdesh Gupta and Arshiya Bose).