I have never been to Mahabs, as they call it. I’ve been to a city that is sometimes known as Mamallapuram, and oftentimes Mahabalipuram. These three places sort of correspond, rough shape and outline-wise, and occupy the same geographical coordinates. The names are used to mean more or less the same area but they are vastly different cities.

I now live in an area called Banaswadi, which I refer to as Bronxwadi, in a town called Bangaloore. And I visit cities of Bengaluru, B’lore, and Bangalore.

This is not a pitch for cities and their names and standardising them. It is not a preamble about how people mangle ‘traditional’ names or how newcomers to a city change it. Perhaps it is a bit of the last, but in a different way.

The city in history, and the city now, and the city of the future - are where my other central thoughts converge: the idea of leisure.

Humanity’s true purpose, its only meaningful pursuit, is the pursuit of leisure. To stop, to contemplate, to perceive not in motion, but at rest, the world around us. Through evolutionary mix-and-match, we were born with brains a bit too big and so we simply lie back and rest, letting the rest of our body catch up with our skull in terms of weight and height and proportion, before we can begin taking those first tentative steps.

Those six to eight-odd months of leisure when we were just born, we must search for and attain through the rest of our lives.

Leisure isn’t idleness, although idleness is supremely valuable and a lost great art. Leisure is the doing of what you would like to the moment it strikes your fancy. Leisure is the breaking off of the chains of productivity and value imposed on me, you, us.

Leisure is the one step behind the great seething mass, allowing you to contemplate the City.

Contemplate the city. It exists, not as a unitary place, but as a shimmering, shape-shifting, amorphous entity which only very rarely corresponds to the physical limits of those things people talk of when they mean a city – the buildings and the streets and the stores.

It falls upon me, and you now, to carve the city I, and you, want.

And we do this by walking.

We walk, and in the walk, we write our city into existence.

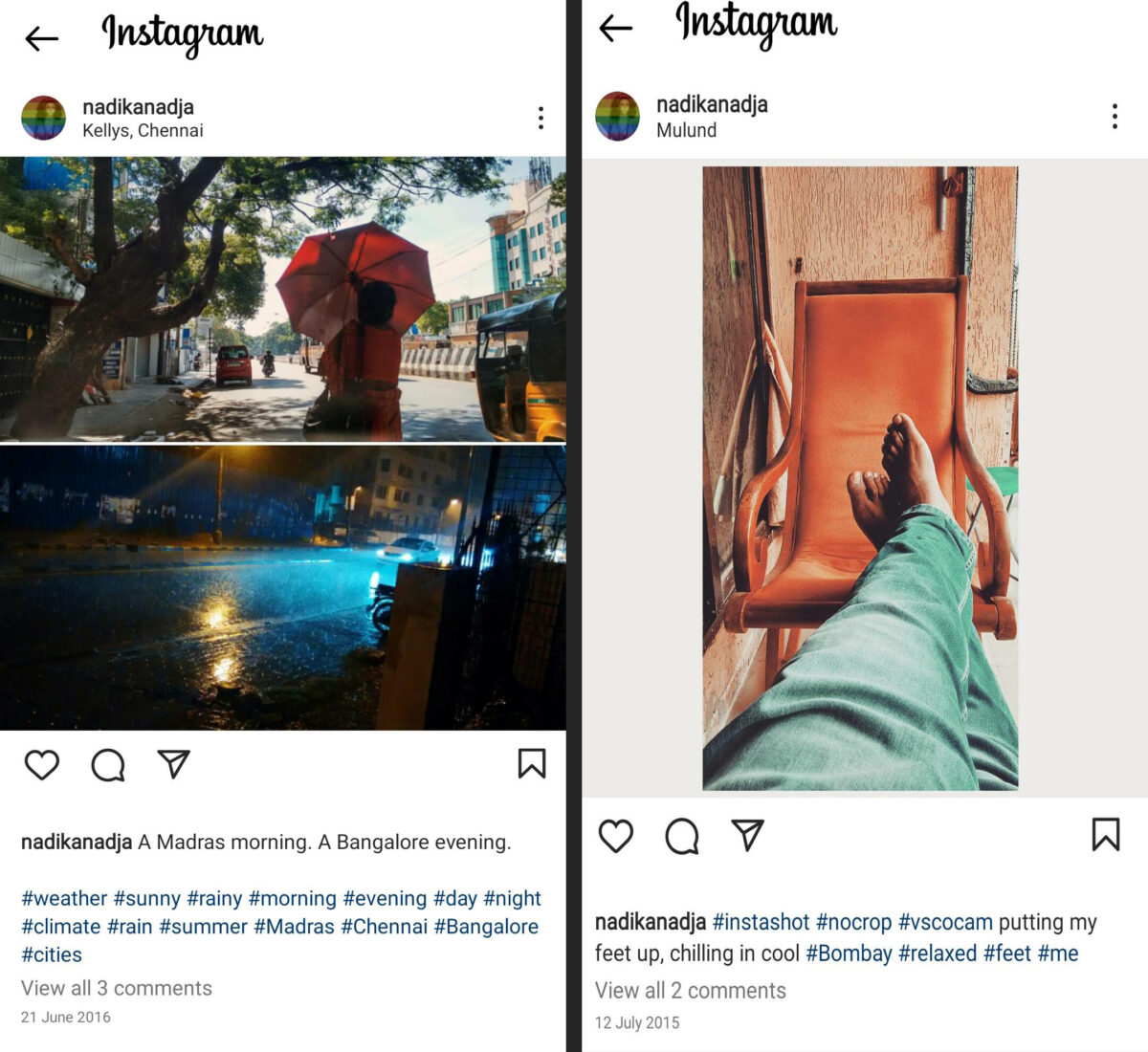

A slow walk, a walk of leisure. Our steps – as we walk – delineate the borders of the city, each step holding them in, to be erased soon as other steps create other cities over, or below, our own city. I once described Chennai as a palimpsest. It is. So are your cities.

The city I walk and create, is not the city you walk and create. The streets I carve out from the terrain of the city, the little stall selling under-priced treasures in the form of old books, the little corner where a young woman and her son mix congee with buttermilk, a generous handful of chopped onions to take the edge off the tang, and a small plate of ‘touchings’ – fresh-cut mango pickle, brined chillies, coriander-mint chutney – that street where I once realised I loved the feeling of sweat beading up and trickling down my face and sizzling as it fell on the pavement: all of these exist for me and only me and I must rescue it from a featureless, faceless map of the city as a machine sees it. Rescue it by walking it and carving it into place, like an ancient architect chiselling away the unnecessary bits to turn rock into temple. That too requires leisure – a step back to see an elephant in a rock and a temple in the shape of an elephant. Stop to observe where the chisel falls and where it needs to, not a rush order. This Madras, this Chennai is not your Chennai.

Nor the Chennai of the aunty next door – who wakes up at four to cook for the entire family, drops the kids off to school and rushes in the opposite direction to a bank job – the first job she’s ever had, the first woman in her family to have one, in fact. Or the old man pulling a long cart down a narrow street – a street now beloved of people for the very things they abandoned it in the past. The aunty, and the old man, they do weave a city into being in their walk, but they may, or may not, remain oblivious to it.

It falls on me, and you, to take that step back and observe the city being created.

Different walks, different cities. Layered on top of and to the side of each other. A palimpsest. Not a productive, purposes-ful walk. One of merely being there, witnessing the amoeba of the city settling into its shape for the day.

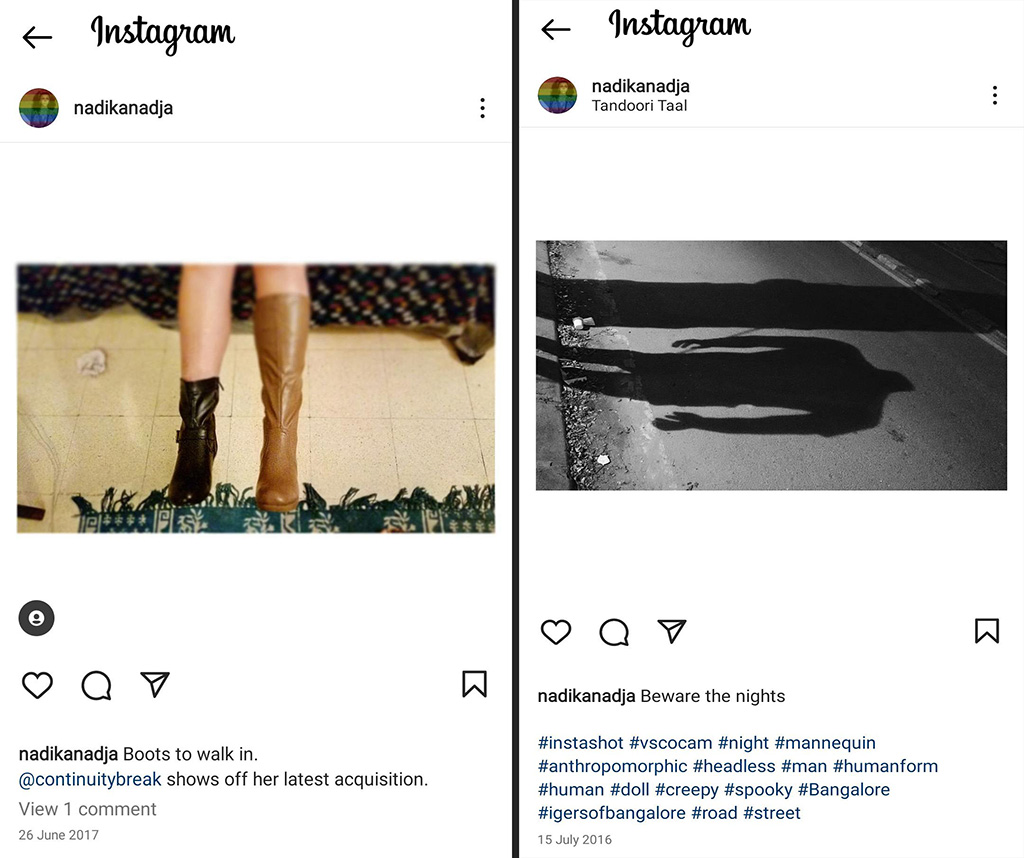

Walk, to create the city. Walk to create a city for a trans woman. Walk to create a city for a disabled woman. Walk to create a city that doesn’t need deep pockets or influential friends.

Walk, in other words, to create a city in your own image.

For we risk other people telling us what our city should be, and where we belong.

Walk, to write the city. A palimpsest. Each layer above and below and to the side a document of extraordinary significance. A historical document. A record of me, you, us.

I wrote into existence a Madras-Chennai in which it was cool, and ultra-digs, to take pleasure in a city that was not the Delhi-Bombay-Calcutta of my ’80s childhood. A Madras-Chennai where the gaps between a temple and a church led to a printing press and one of the earliest Bibles to be printed in an Indian language. A walk in which I spent time through the 1600s, 1700s, 1800s, to arrive in 2002. A leisurely walk.

The leisure to wake up at five a.m. on a Wednesday to go to a distant pier, to imagine masted ships and billowing sails docking here in the 1870s to buy fresh fish for the white traders in brown city. The leisure to rush across the street, weaving in and out of peak hour traffic to take a photo of a hairy spider on a blue lock. A blue lock against a blue door set in a once-blue-now-peeling wall of old bricks and older masonry.

Place making. An architect-city-planner term for building an atoll of green amidst a sea of grey concrete.

Place making, a loiterer-leisurer-walker idea of finding and writing and creating the city. Place marking, a gap. Gaps are lovely, they let you see an old man walking down a narrow lane, the columns of old houses boxing it in, holding the man in place as he too walks – not going anywhere in particular, after a lifetime of going somewhere important.

Elsewhere in a different month, another old man shuffles and squats in the gap between the base of a lamp pole and a shut door. A hot sun beats down but he pulls himself in, sitting exactly in the shade of the pole. He is set here. There is shade, and he has the time. It is a Monday and there is an office to go to, but there is a place and time for this. It is here, now.

Like Charles Baudelaire and Michel De Certeau before me, and perhaps after me as well, I am a flaneur (would a trans woman be a trans-flaneuse?).