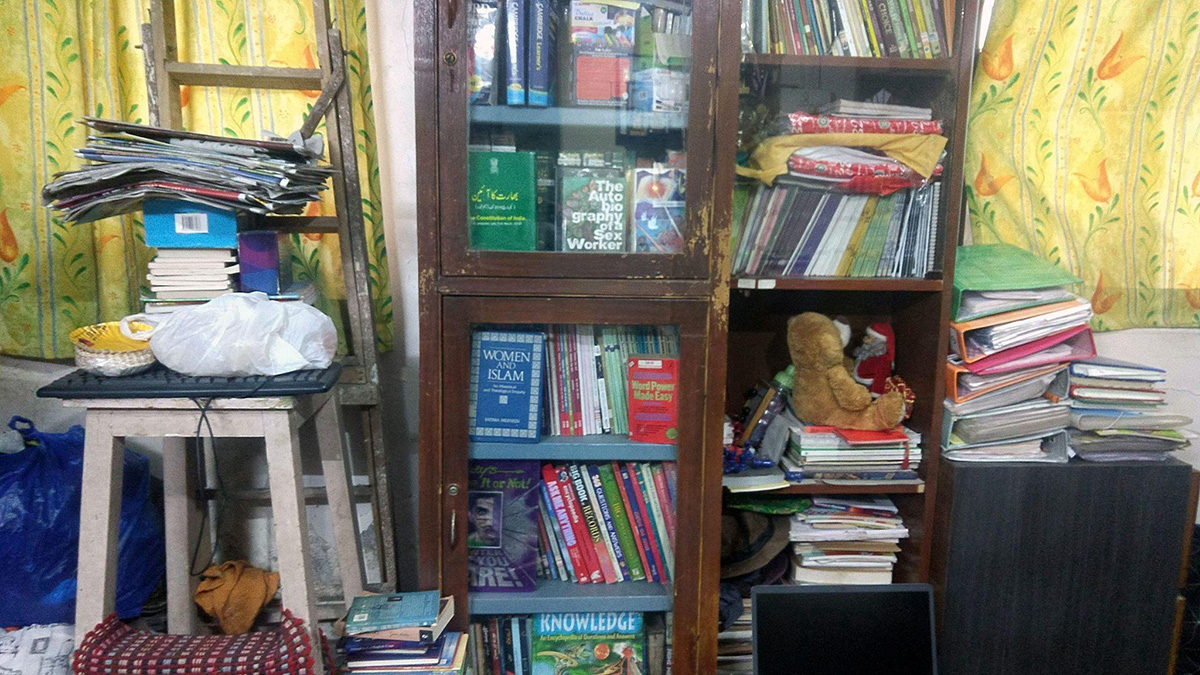

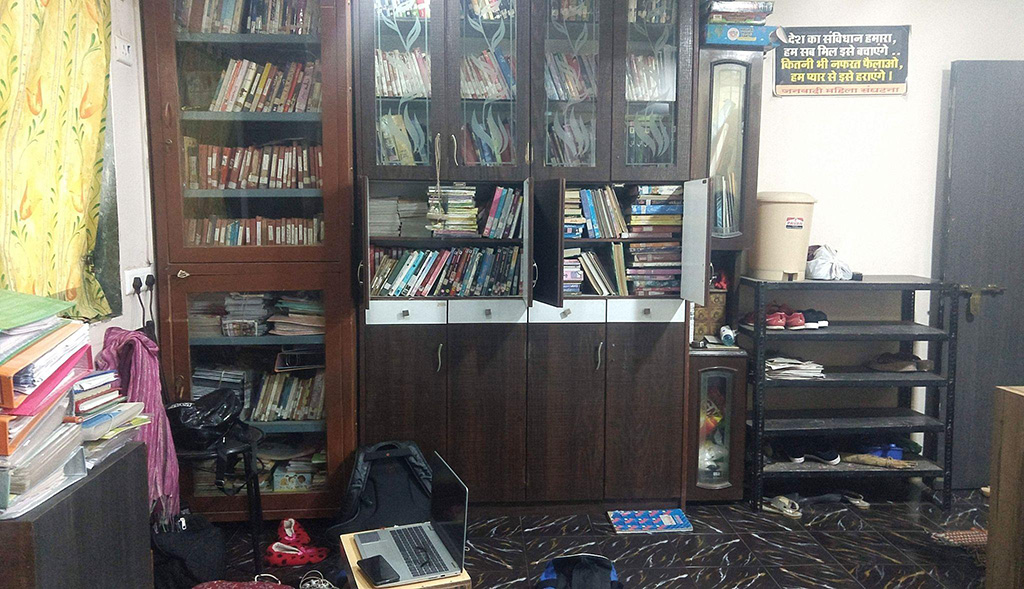

“Education must be spoken about outside the school. Being a student is easier outside the school,” believes Saba, who has been running the Savitribai Phule Fatima Sheikh Library with a team of educators (ex-members of the library) in Bhopal since 2010. She was referring to the library and its potential to be an educational institution, perhaps one that is more inclusive than a school itself.

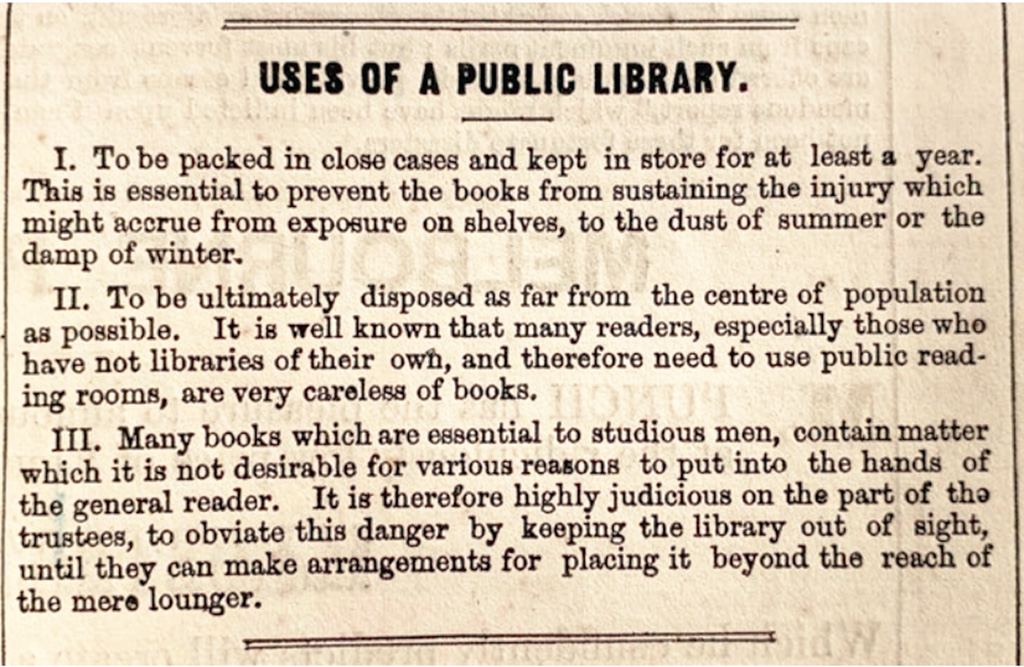

Knowledge is power and often finds itself in the hands and shelves of the powerful. It is kept behind closed doors, glass shelves and ironclad locks. Amongst the many casteist and misogynistic verses that constitute the Manusmriti, two verses declare “Shudras and women” unfit for education and promise hell to all dissenters. Even in early Buddhism, women were considered ineligible for salvation, and were hence denied religious education. Later, when the colonial regime of power came into picture, public libraries were introduced into British colonies with deep caution, as can be seen here:

This is not only true for India. Virginia Woolf has written about how a woman’s entry into the college library in the British “motherland” was earlier conditional on her either being escorted by a Fellow of the College (spoiler alert: only men were allowed and could afford to go to colleges with good libraries then) or possessing a letter of introduction. Historically, libraries were not only spaces of male occupation but also considered “dangerous” for women.

If only books could be kept locked and “beyond the reach of the mere lounger” that easily. Marginalised communities have time and again broken these locks and laid claim over knowledge and spaces and institutions of knowledge, whether it was the mill workers’ libraries in colonial Bombay or Phules’ and Fatima Sheikh’s initiatives to teach Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi and widowed girls.

The politics of community libraries is located in this history of knowledge where books continue to not only reach but also empower those who were never supposed to touch them.

If not community libraries, then who?

How did these community libraries (libraries owned by the community or with the community as the primary stakeholder) come about? One clue might lie in the declining state of public libraries.

Public libraries are a state subject in India but only 18 states have passed this legislation. A study, A Policy Review of Public Libraries in India, published in 2018 by Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS), notes that states with low literacy rates have no library legislation. Due to a variety of reasons ranging from legislation to intent, public libraries are facing acute shortage in infrastructure, funds and member engagement, resulting in an ‘information drought’ amongst large sections of the Indian population who do not have access to basic reading materials.

Public libraries are meant and were envisioned to be community institutions, contributing to the upliftment of communities but the IIHS paper claims that in the past 70 years, no concerted efforts have been made by the Ministry of Culture to develop the country’s public library system.

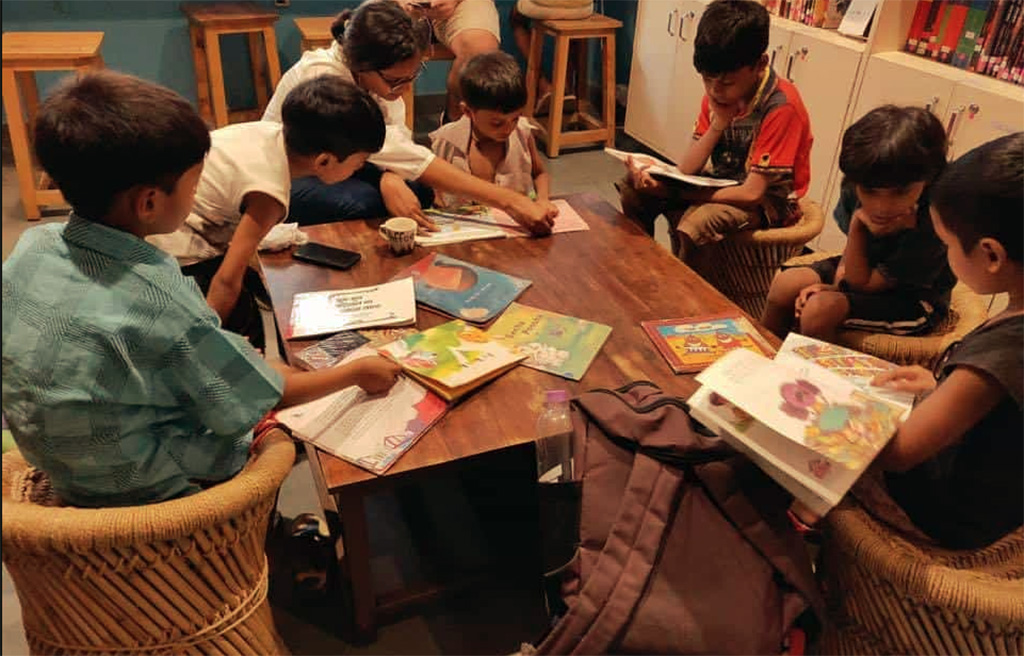

Another clue lies in the worsening public education system in India. In a series of interviews conducted by Parag in 2020 regarding libraries and their relationship with education in India, educationist Krishna Kumar argued that the public/community libraries were meant to facilitate the success of the school/university libraries. Libraries that are open and accessible to the public at large encourage a culture of reading among adults who can then pass the habit on to their children. Moreover, children can use it to further their reading during vacations. Like Krishna Kumar, even India’s policies on education have imagined such libraries to play a supplementary role in relation to the formal educational system. Krishna Kumar also said, “A school’s soul lies in its library.” If he is right, many schools of India are seriously deprived of their souls.

Behind lock and key

When they were asked to speak of their school libraries, many learners in the libraries spoke of locks.

Either the libraries themselves were locked or the books were locked behind glass shelves, opened only during a special event by the librarian. The reason? Children damage the books and so, they must be kept away from their reach. Common were stories of students bunking the library period or even school in case they had forgotten the book they had borrowed at home. Prachi, the curriculum designer for TCLP, narrated, “Some children stand outside the library for months because they associate fear with the library. What if they lose the book or damage it by mistake? Even for us, the quality of books matter. We don’t believe in poor libraries for poor people but in excellent libraries for everyone.” Is a community library, then, a place where one comes to heal from the carceral nature of the Indian educational system?

The librarian of TCLP’s Khirki library remembered how she did not like her school library because, as she was the tallest in her class, she was always at the end of the line and got the leftover books to borrow.

Ritu, one of the learners who attends Adhwan’s library sessions, told me that in case there was even a slight accidental damage to the book, she would get remarks on her calendar which would then affect her grades. The experience of the school library, for many, was forcedly borrowing a book (often not based on one’s interest) and reading it silently while the class monitor watched you.

Sumit, a travelling librarian and head of student council at TCLP, said, “Kitaab kaagaz hai. Kaagaz toh fatega hi. Agar koi kitaab aasani se damage ho rahi hai, toh humein nayi kitaabein khareedni chahiye na?” (“Book is paper. Paper will obviously tear. In fact, if it’s that easy to damage a book, shouldn’t we procure new books?”)

S.R. Ranganathan, regarded as the father of the library movement in India, came up with Five Laws of Library Science. The first one is “Books are meant for use.”

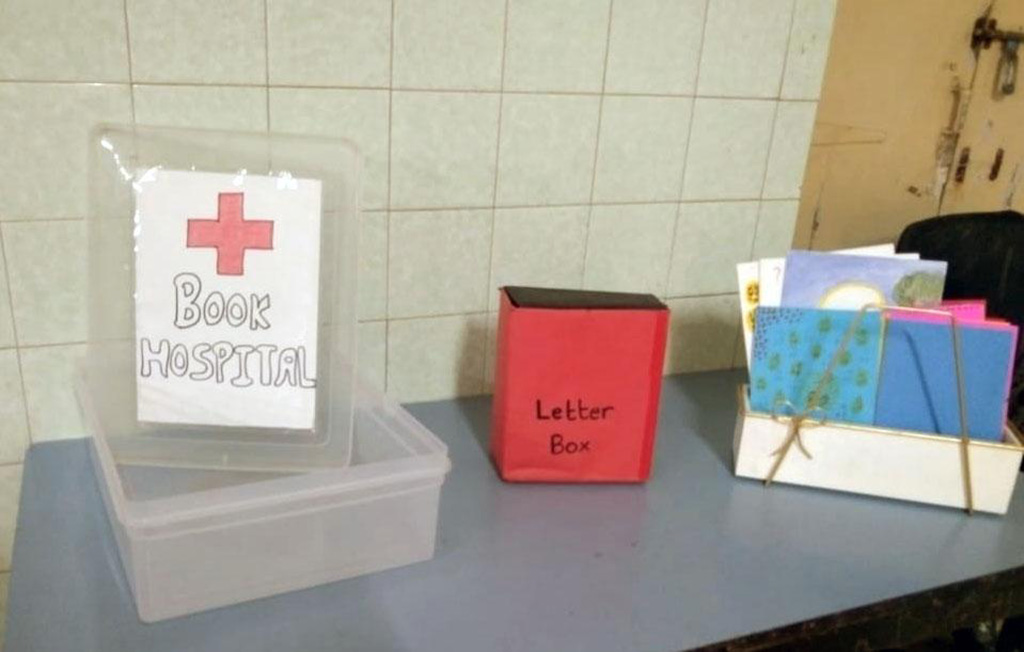

When TCLP members damage the books by mistake, they take them to the librarian and both the librarian and the members work towards repairing the damage. In fact, in Adhwan’s library sessions, there is a ‘Book Hospital’ where a learner is supposed to repair a book in case they have damaged it. The fear of losing/damaging a book is not worth the cost of ending a learner’s reading journey.

The librarian at TCLP Khirki told me that many members of the library live in small homes where they are often asked to take care of their younger siblings when their parents are at work. Initially, when their younger siblings would damage the book or if it got wet due to rain, the members used to stop coming to the library, scared that they would be punished. It took time and persistent efforts on the part of the library staff to convince the members that no damage is irreversible. This protection and sanitisation of books as sacred are Brahminical ideas, and make knowledge exclusive. Perhaps, this is why community libraries have been central to Ambedkarite movements. Bookstalls are a common sight at Ambedkarite events and are considered essential components of every celebration.

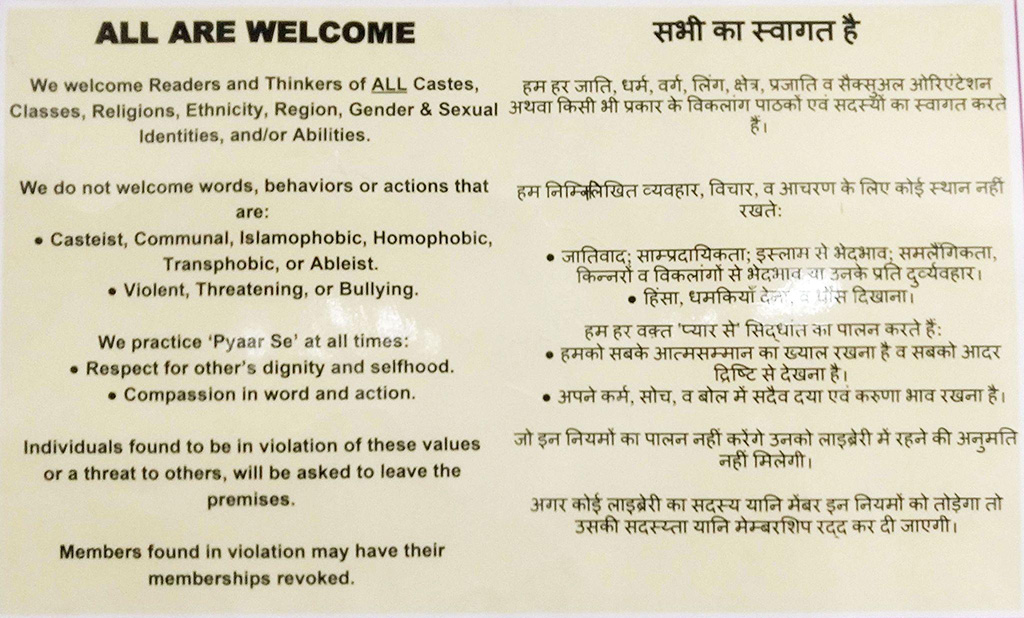

TCLP libraries have a “Pyaar Se” (with love) motto, which is meant to guide all conversations and activities inside the library. Members (largely students in middle school and high school) spoke about it fondly and juxtaposed it with corporal punishment in school. The fact that no one hits the learners when they make a mistake is, for them, a big difference between their school and the library.

Absence of punishment does not mean absence of pedagogy.

At Rehenuma, Hamida, a teenager in high school, explained to me how she was taught punctuality in two different institutions. In school, when she used to come late, she was made to run two rounds of the field before she could enter the class that had already started without her. She did not really understand why gates were closed for those who came late and was used to missing the first two lessons of the day because she commuted from Mumbra to Thane for school. But in Rehenuma, no session starts without everyone’s presence. When Hamida came late to one of the library sessions, the librarian, Faiza, sat her down and explained to her why punctuality is important. “Sirf mere late hone ki baat nahi hai. Koi mera intezaar kar raha hai.” (“It’s not just about me being late but rather that someone is waiting for me.”) She was not punished, and she understood.

Thus, into this vacuum left by state-run public and school libraries, community libraries have stepped in to save what they can, one more book and one less lock at a time. These libraries are bridging the deep gaps in learning of those in the public education system. In addition, many community libraries are formed as a response to the systematic abandonment of certain communities by the state. Most of these libraries are located within bastis with predominantly Muslim and Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi populations.

Literacy and libraries

Public and community libraries are also places that help people ease their way to the written word. The community libraries I went to taught Hindi and English fluency either officially or unofficially. According to a sample study conducted by Azim Premji University in January 2021, on an average 92% of children have lost at least one specific language ability from the previous year across Classes 2 to 6. These specific abilities include describing a picture or their experiences orally, reading familiar words, reading with comprehension, and writing a simple sentence based on a picture.

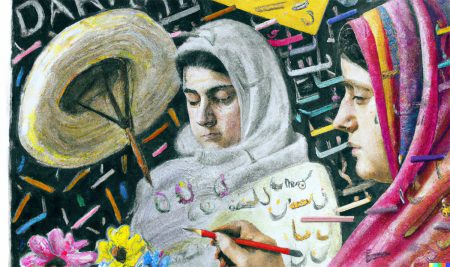

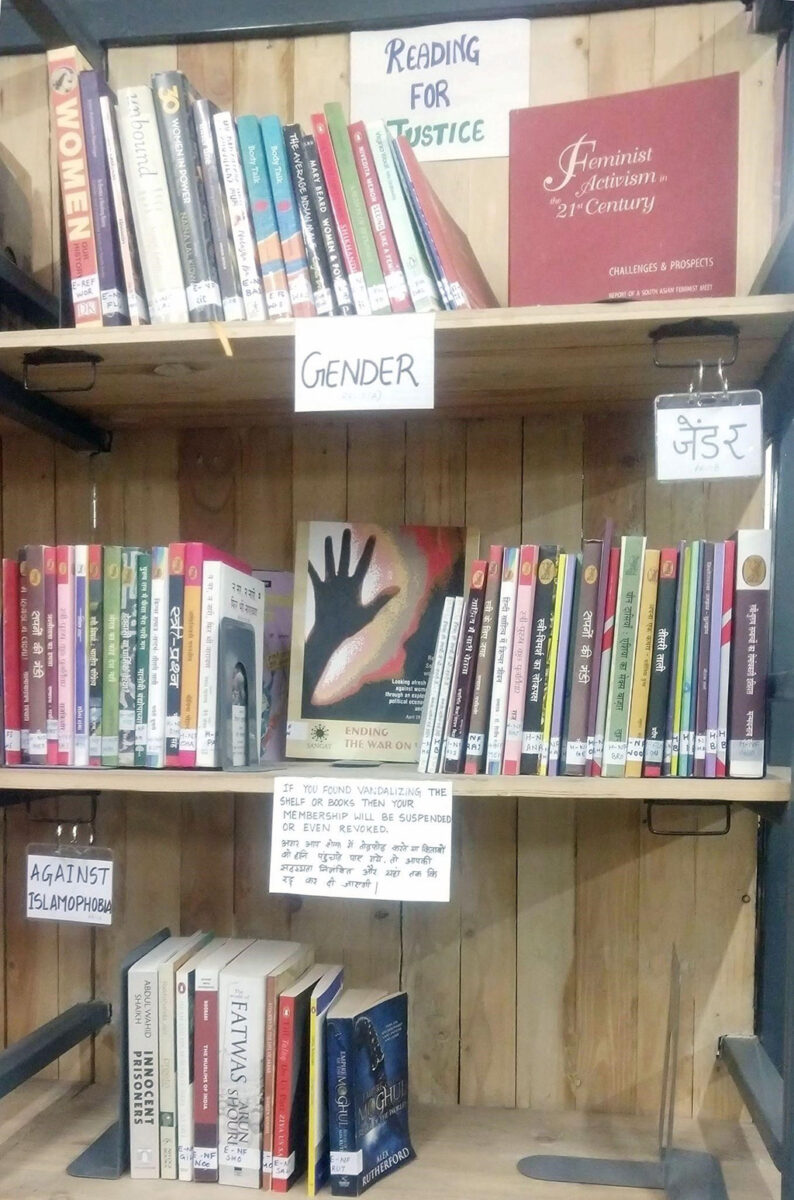

The feminist library

“We try to create opportunities for everyone to speak. But, sometimes, in common discussions, a 12-year old boy would raise both his hands and insist on going first. So, all educators try to not give in to his stubbornness and go by a certain order of speakers. Boys sometimes feel that they are not able to wield power here because everyone is free there. No one person is in control. I think that because girls have this habit of being patient, they sit quietly waiting for their turn. A boy may even get up and leave because he does not want to wait. But, we try to not worry too much or spend a lot of energy in getting them back.” – Saba, Savitribai Phule Fatima Sheikh Library, Bhopal.

No librarian-educator said that they would not like to invite boys into their space. In fact, it was a difficult political choice for Rehenuma to run a girls-only library in an area where young Muslim boys would also want to access books and reading material. But they recognised that the girls would lose their space if too many boys start coming, either because of their own discomfort or that of their families’.

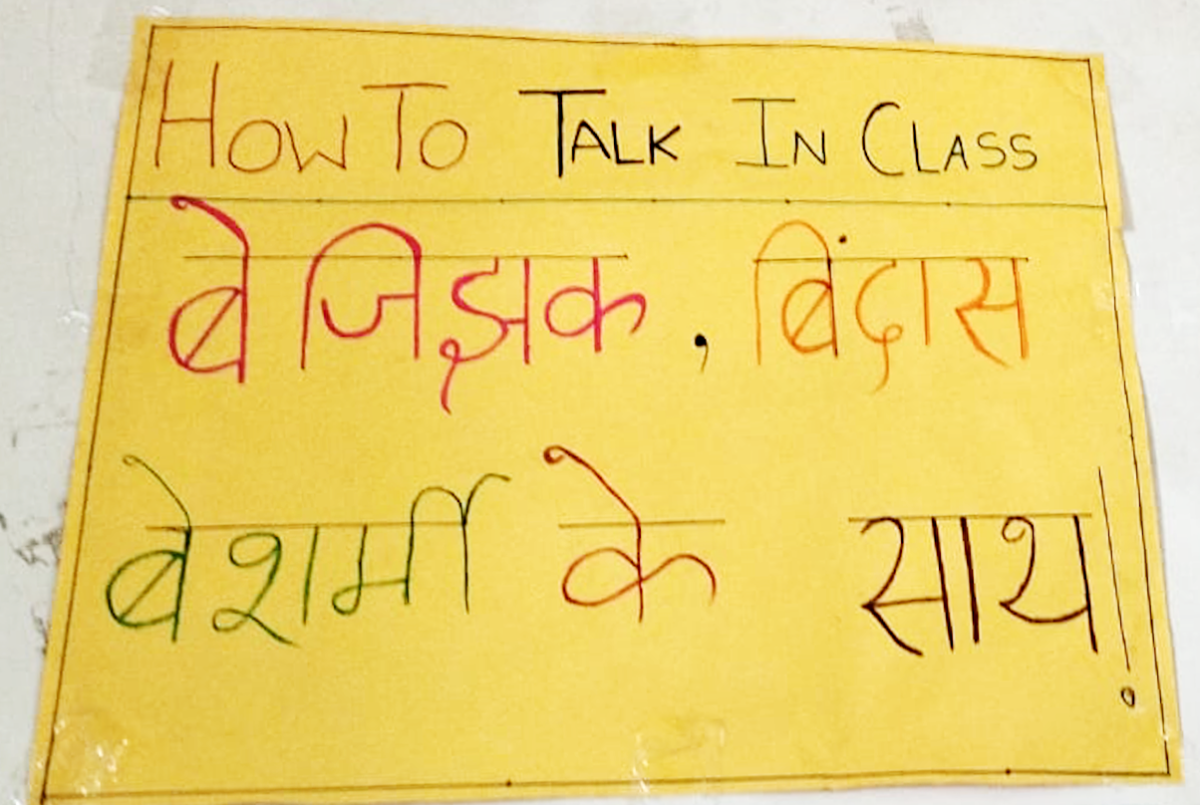

In every community library I visited at least once I heard a woman or a girl say the equivalent of, “Earlier, I was unable to speak to elders. But now, I can talk to anyone.” (“Pehle main bade logon se baat hi nahi kar paati thi. Par ab main kisi se bhi baat kar sakti hoon.”). This “bolna” or “speaking” is different from literacy and signifies a combination of confidence, courage and articulation. It is not just speaking but speaking for oneself, debating with elders, making friends, sharing personal experiences, and connecting the dots between knowledge and experience. How does a girl learn to speak in a society where “zyada bolne lag gayi hai” is a cross-country jeer?

“Earlier, we used to just stay at home and not talk to anyone. But, now that we have come here, we even talk to men. We had no knowledge about the law. We got to know about the rights of women and children. Even these kinds of things happen here. Lawyers come and talk to us,” said Zahra, a middle-aged woman in Rehenuma.

Rehenuma Library has a rule which basically translates to, “Whatever is spoken of in the library stays in the library.” This allows the women and girls to be able to share their personal experiences here without being afraid of anything getting shared outside. They bring incidents from their homes, colonies, schools and colleges into the library, but make sure that nothing leaves it. One of the older women in Rehenuma said, “Dil ki baat bhi bata dete hain. Halka ho jaata hai man. Ek saath apna dukhda ro lete hain.” (“We let out what is in our hearts. We feel lighter after that. We even weep together sometimes.”)

What did these libraries do during the pandemic?

In 2020, 1.5 million schools closed down due to lockdown restrictions for almost two years, impacting the education of 247 million students enrolled in primary and secondary schools. Online education became a buzzword overnight but only one in four children in India had access to digital devices and internet connectivity.

The Annual Status of Education Reports (ASER) found that when the schools were closed in 2020, barely one-third of all enrolled children were receiving learning resources and activities from their schools. This number remained the same one year later in 2021. The proportion was lower in government schools as compared to private schools, which means that the education became more expensive, especially for disadvantaged households.

(The same report found that almost 40% of children avail paid private tuitions.)

During this period, school and public libraries also closed but the community libraries tried their best to respond to the needs of the community and stay connected to their members. When students were not able to reach schools, the libraries managed to reach its members.

Jatin Lalit volunteered at TCLP and decided to open a community library in his village of Bansa in Hardoi district of Uttar Pradesh in December 2020. This was bang in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic, right after the first wave which had seen hordes of migrants return to their hometowns and rural learners finding themselves at the short end of the digital divide. Bansa Community Library and Resource Centre had a massive gap to fill. Students were deprived of their schools and competitive exam aspirants were finding it tough to migrate to bigger cities like Allahabad and Kanpur. Jatin says, “Here, unlike the cities, the concept of a library, especially as an educational institution, is very new. Education still only means schools and colleges here. During Covid, the classes were still on through WhatsApp or Google Meet in the cities. But here, there was nothing. No dialogue between teachers and students. So, we had to start classes in the library.”

TCLP in Delhi, for instance, started Duniya Sabki, an online library initiative where libraries sent books to the members via WhatsApp. For those who could not read, voice notes with narration of stories were sent so that they could continue listening to stories.

Vacha arranged for smartphones, complete with mobile internet, for the girls who had no other way to attend their classes. Many learners attended their online classes and even wrote their exams sitting in Rehenuma because their homes did not have phone network signal, let alone internet connection. Rehenuma also became a place for many children to continue their learning informally, after having dropped out due to financial or religious reasons. Some girls are studying in Rehenuma and plan to write their board exams independently.

Adhwan Foundation made sure that the girls in the rescue home could access books even if the members were unable come there to conduct activities.

In a raging pandemic, within a promise of Digital India, its community libraries that acted as bridges between learners and digital education.

The public library movement in Kerala and Karnataka are exceptions in a landscape of failing public libraries. P.N. Panikkar, who is considered the father of the library movement in Kerala, led the Travancore Library Association in 1945, consisting of 47 local libraries with the aim to encourage reading and literacy. After Kerala gained statehood, the state government took cues and acquired this association, naming it the Kerala State Library Association, which had 6,000 libraries associated with it by now. If Kerala’s public library movement has a rich history, Karnataka promptly looked towards its libraries when Covid-19 became a barrier between students and schools. Oduva Belaku (Light of Reading) was a programme that started by late 2020 when the pandemic had shut down schools. The aim was not to open up new (digital/online/technological) pathways towards knowledge or create something from scratch but rather to revive the public libraries. This was done not only by material renovation but also by making library membership free across all rural public libraries.

Libraries IRL

“Our friends live very close to us but we do not meet them. So, all of us meet here and a lot of gossip happens here. No time spent here is enough. We aren’t able to talk enough in our homes. We even fight when we want to. All of us are mostly from different schools: rarely will there be two of us in the same class in the same school,” an older college-going girl in Vacha said.

Among the libraries I visited, TCLP’s three libraries were the only ones that were co-ed. All the other libraries were girls-only. In TCLP’s Sikanderpur library, the boys told me during a group discussion that they are not allowed to hang out with their friends who are girls anywhere else besides here. The schools are either boys-only or girls-only, and having a friend who is a girl is considered a taboo. A boy said that he was slapped by his uncle when the latter saw him walking with a girl in their neighbourhood. The library, then, becomes a safe and non-judgemental space where boys and girls can interact with each other. The possibility of inter-gender friendships exists in the space of this library the way it cannot exist in any digital library or e-library.

Iqra, a girl who recently joined Rehenuma library (girls only), tells me that her parents are extremely strict. It took her 11 minutes to reach the school and 11 minutes to reach home from school. The moment she took 12 minutes to reach home, her parents demanded justification. The same continued when she joined college. But, with Rehenuma, she can be two or three hours late, and nobody in her family asks her any questions. I asked Iqra, “Is this because this is a girls-only space?” She responded, “No, because both my school and my college are girls-only. So that can’t be it.” She thought a bit more while I was talking to the others. This was baffling to her too.

Zahra, one of the middle-aged learners in the library and a mother, said, “My husband tells me that if I am going to get a book from the library, I should go. If it’s the library, then there’s permission. We can’t tell them that we are going out for no reason. We can’t say, ‘We will hang with our friends for a bit,’ or ‘We will go enjoy ourselves and be back.’”

Saba, from Savitribai Phule Fatima Sheikh Library in Bhopal, narrated how many young girls are not allowed to comb their hair in a ‘designer’ manner at home. “Her grandmother will ask her why and for whom she is combing her hair beautifully. She will make sure her hair is untied. But, in the library, when they are all sitting together, they will tie each other’s hair. They even put on lipstick sometimes. They sometimes remove it all before going home. Sometimes, they give the excuse that their friends made them do it to their parents.”

This does not mean that the libraries receive unconditional support from all families at all times. This confidence and knowledge that many women derive from the books and activities in the library are not something their families take kindly to. The learners tell me that their families often tell them they have started arguing a lot since they have been going to the library. “Bahut bolne lag gayi aajkal.” The trust in the library and the discomfort with their daughters’ and wives’ changing voices go hand in hand.

Schooling the system

A common argument against free libraries is that people do not respect or value what they get for free. How can you/dare you care for something without having paid for it? But these learners do not value the library like a service. They protect it like their own. Not only are they consumers of the services of the library but often they also facilitate the relationship between the library and the community within which it is located. In Vacha’s library, the girls proudly told me that they wrote letters to the local political leaders to get the space of their library for free. In TCLP, interested library members have the opportunity to become student council leaders and participate in the management and functioning of the library. After a certain age, they are also eligible to officially intern for the library, and the library supports and even offers various pathways of employment. Thus, the library performs the role of essential infrastructure in the education, liberation and the future of these communities, which immediately goes outside the scope of paid libraries.

All the libraries I have mentioned above are directly or indirectly NGO-based or people’s initiatives when they should be state’s initiatives. It is alarming that the institutions from where students are actually learning vocational, reading, speaking, and interpersonal skills are not recognised, let alone supported, by the government.

Free Libraries Network is a platform built by TCLP that connects free libraries to each other so that librarians, activists and educators can learn from each other and support each other in the journey to build accessible and equitable libraries in every area. While the community libraries described in detail in this piece are predominantly located in urban areas, there are many rural community libraries which are opening up and starting a culture of reading from scratch in villages that have had no imagination of a library. One of these is Seemanchal Library Foundation which opened three libraries (named after Fatima Sheikh, Savitribai Phule, and Begum Rokeya) in Kishanganj district in Bihar in January 2021. Disillusioned by the possibility of any support from the state, Saquib, the founder of Seemanchal Library Foundation, said that being part of the Free Libraries Network makes him feel less alone.

A girl in Vacha said right at the very end of the discussion, “If I have to explain what this place did for me, I will say that I learnt to recognise myself internally and externally. Here, we learnt who we are, how people see us, and how they should be seeing us.”