This is a reported piece on the student groups at IITs, who work on educating and building awareness around caste-based discriminations in Indian institutes of eminence, particularly engineering institutes. These groups work under the larger aegis of Ambedkar Study Circles, which exist outside campuses too.

All names have been initialised and anonymised.

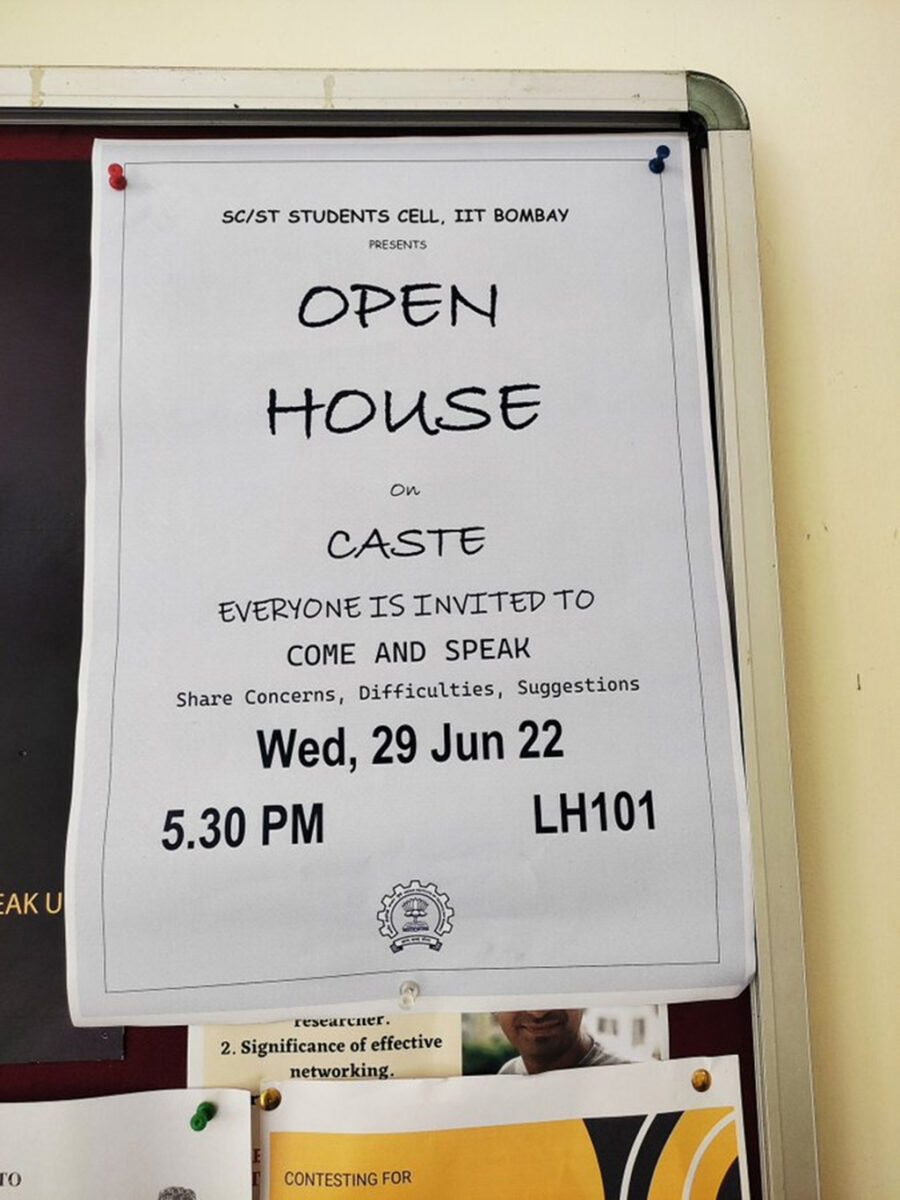

The student groups interviewed are the Ambedkar Periyar Study Circle (APSC) of IIT Chennai, the Ambedkar Phule Periyar Study Circle (APPSC) and the Ambedkarite Students Collective (ASC) of IIT Mumbai.

“Political movements should start from books, actually. Education is the primary concern, the preliminary concern. Only then we can organise. From the book[s] only we can start.”

– S, Ambedkar Periyar Study Circle of IIT Chennai

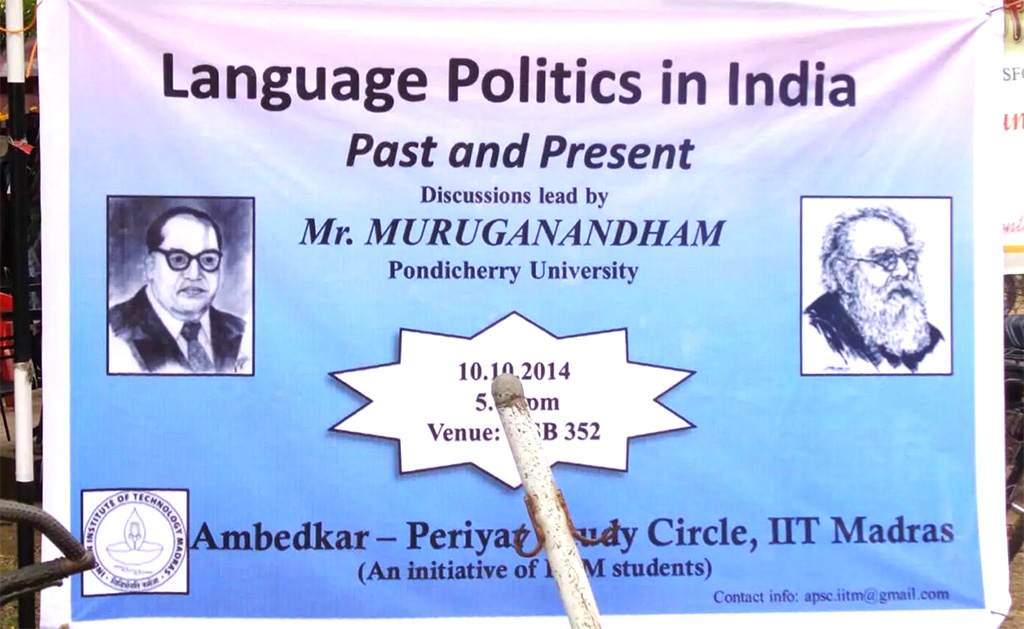

Since their conception in 2014, the Ambedkar Periyar Study Circle in IIT Chennai has been no stranger to controversy, media attention and public scrutiny. Its members have led a charge of Ambedkarite assertion on a campus colloquially called the ‘Iyer Iyengar Institute of Technology’.

Their reputation in those initial years seems particularly outsize considering that for the longest time, the APSC just consisted of four members, who held meetings in their hostel rooms.

“It is important to tell this story again and again…Back then, the days were [such that the acknowledgement of] caste as prominent in higher education was not-so-obvious a fact,” says A, one of the original 2014 founders of the Ambedkar Periyar Phule Study Circle in IIT Mumbai.

The first anti-caste group in any IIT—the Ambedkar Periya Study Circle at IIT Chennai—was born into this milieu on Bhim Jayanti in (14 April, 2014).

“Our plan was to build a base, actually. I thought that war was coming,” says S, one of the founding members, matter-of-factly.

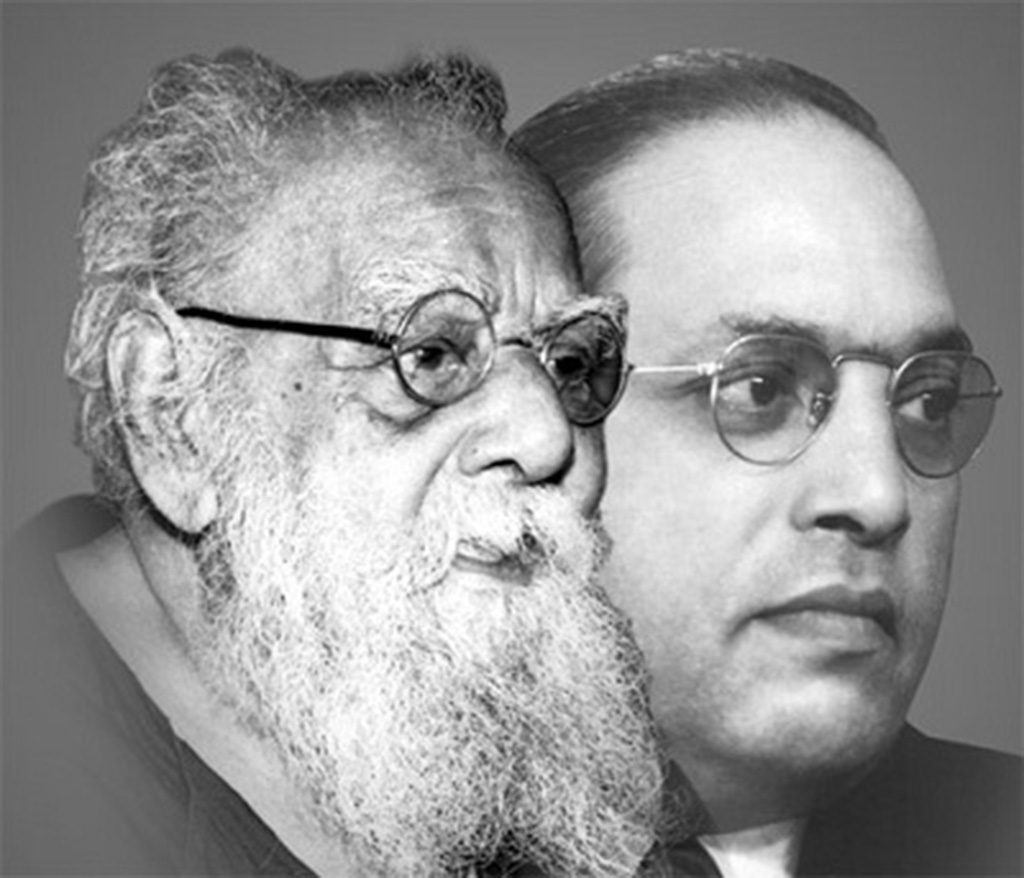

As per their founding statement, when there were discussions to decide on a name for the study circle, “there were no second thoughts from anyone in using the names of legends Ambedkar and Periyar, who led an uncompromised struggle on the ground against Brahminical hegemony. As expected, the administration was not receptive to the names of Ambedkar and Periyar, but students were not ready to compromise…”

The Ambedkar Periyar Phule Study Circle in IIT Bombay formed out of the campus ferment from first-year dual degree electrical engineering student Aniket Ambhore’s institutional murder on September 4, 2014. He was 19 years old, a talented guitarist, and had been a high scorer in all his high-school exams, not to mention clearing the IIT JEE.

An enquiry committee was set up to investigate his death, but the resulting report is still not publicly available.

The founding members of APPSC had initially come together to protest the administration’s misrepresentation of an institutional murder by framing Ambhore’s death as a casualty of poor mental health. Even with active demonstrations and considerable media furore, the administration and government agencies continued to circumvent the driving role of caste discrimination in favour of an individualising narrative. In other words, just the unfortunate result of academic pressure imposed on an ill-equipped student unable to cope with its demands.

Despite a reputation for scientific reasoning, progress and development, elite institutions in India have gained notoriety for carrying out the opposite in policy and day-to-day administration. The globally recognised IITs aren’t any different, what with administrators seriously entertaining religiously sanctioned demands for separate washbasins and dining halls for vegetarians and non-vegetarians. There are reports of pervasive and systemic discrimination, harassment and abuse, affirmed and documented in research studies, academic texts, fact-finding commissions, and Round Table India articles cross-referenced by the expressions of the lived experiences of caste-oppressed students and faculty members across the IIT network.

The APSC opposes this “hardwiring of casteism” by taking inspiration from the “uncompromising” politics and evergreen relevancy of Ambedkar and Periyar.

“One thing is, people should know that we have nothing to hide. We’re political. We’re not neutral. We have a stand [which is that] the primary contradiction of Indian politics and Indian society is Brahminical hegemony,” S states firmly.

Beating of the drums

Culture is one to disrupt and recontextualise.

While film screenings and book discussions are a staple of campus activism, the members of the APPSC felt that they required a distinct cultural programme or outlet to express their politics and dissenting values. So, they decided to learn how to play the parai drums together.

Parai is one of the oldest percussion instruments, dating from the ancient Tamil Sangam era. These drums are made of cowhide stretched over a hollow frame of wood from a neem tree; they are beaten with sticks of varying dimensions. Scholars generally acknowledge that its music had crucial sociocultural and spiritual functions. But, under Brahminical hegemony, the parai is a funeral instrument, and performing paraiattam (the folk dance associated with the drumbeat) is a forced caste occupation of certain Dalit castes across Tamil Nadu. Its association with death, alignment with Dalit communities, and the physical material of the drum itself stigmatises the art form and its artists in the eyes of caste Hindu society.

In 2018, the APPSC joined Dharavi residents in learning to play the parai drums from the anti-caste cultural activist troupe Neelam Kalai Kuzhu. ‘…We want to bring that culture of resistance to the campus. It was a conscious decision to choose parai, …it has that history…that kind of culture [that] we want to be a part of, and we want the organisation to be a part of that larger collective,” says A.

Accompanied with lyrics of dissent, liberation, equality, Ambedkarite-Periyarist ideals, and labour politics, woven with assertion and rage, emergent parai became a tool for struggle and change in the hands of activists and Dalit community members. Weekly practice sessions on the campus grounds proved excellent for building a sense of community, as people tended to go have chai after, talk amongst themselves and connect.

Desert flowers

Following Ambedkar’s 1936 blueprint for “effectively fighting the Brahman Raj”, and “with the intent to educate”, the APSC promotes “rationality, pragmatism and modern science”.

So, in the days leading up to a planned APSC event, the members would write their pamphlets, distribute them at messes, go door-to-door to different hostels and spread the word. “We printed 500 pamphlets and circulated them. If you’re giving a pamphlet and talking, there will be a face-to-face conversation, questions will be raised, and we will answer;

500 pamphlets means we had 500 conversations,”

explains S.

The activity in question was a lecture by Dr. R. Vivekananda Gopal, head of the Tamil and Translation Studies Department of the Dravidian University in Andhra Pradesh, on The Contemporary Relevance of Dr. Ambedkar, organised by the APSC on April 14, 2015, to commemorate Bhim Jayanti. The pamphlet contained excerpts from his lecture critiquing divisive politics.

But on May 24th, 2015, the APSC was derecognised, stating alleged “controversial” pamphlets and posters for circulation. At IIT Chennai, student groups have the option of being recognised, which means that they have access to student email servers to send mass emails with information about upcoming events, have permission to put up their own posters and also have to have faculty supervisors to support and aid their work. The campus administration said the APSC had used IIT’s name on these posters without permission and the “controversial activities” they had engaged in were a “misuse of their privileges”.

The APSC immediately issued several statements registering their protest at this decision. But no one could have predicted the wave of solidarity that would awaken.

IIT Chennai’s APSC’s derecognition put them in a hurricane of media attention, and even as the controversy raged on in mainstream news cycles, Ambedkarite groups “bloomed across the nation”. At last count, there were around nine to 10 groups across engineering institutes.

A week later, IIT-M reversed the derecognition.

But, a little more than a year later, the administration banned pamphlets on the IIT-M campus.

Going back to Babasaheb?

Professor V. Geetha, feminist activist, educator, translator and editorial director of Tara Books, is no stranger to the reviving power of Ambedkarite education. Over decades, her involvement in the intertwined spheres of feminism, Amedkarism, labour and Dravidian movements, and Periyarism led her naturally to Ambedkar. (Tamil has the most number of Ambedkar’s writings translated, which is another reason they are so accessible to Tamilian readers.)

During the “dreary pandemic summer of 2021 when we were all depressed”, she conducted an online lecture series called Let’s Read Ambedkar hosted by the US-based Ambedkar King Study Circle. It was built off of workshops on Ambedkar’s writings and politics that she had conducted offline across Tamil Nadu for around five years before the pandemic. She explains that a large part of her educational work was requested by Ambedkarite groups, reading circles, unions, book clubs and community workers across a vast diversity of geographies, contexts and classes in Tamil Nadu.

She says, “For me, again, at every step, I’m learning as much as I’m supposedly teaching because I got to know of the presence of these amazing Dalit [and Ambedkarite] cultures of learning, of supporting education. Of investing in Ambedkar—constantly keeping that sense of his life and struggle in the foreground.”

The Ambedkar Students Collective (ASC) was born around 2018 out of a disagreement between some of the newer and older APPSC members in IIT Chennai. Their conflict stems from a difference in ideology regarding representation. The ASC believes that anti-caste groups, especially those claiming an Ambedkarite tag, should be exclusively so. As member T explains, “take internal representation seriously” by taking cognisance of the fact that leadership positions were being filled by Savarna members in APPSC.

The APPSC rebuts the ASC’s critiques, as it defines its understanding of Ambedkarism as a wide umbrella for progressive politics in general—an age-old ideological conflict between Ambedkarite, Bahujan and Left college parties and student groups.

APPSC’s current demographics are all non-Savarna, but it maintains that the way it functions always prioritises practicality, and decentralised participation, implying that it doesn’t matter who fills the official roles when all decisions are only made after a long and deliberative consensus.

While the ASC members also study, discuss, write and learn together, they explore topics like Dalit selfhood, gender issues in Bahujan politics, constitutionalism, academic perspectives on caste dynamics, etc. Representation, in their view, is crucial because they want their group itself to be a space for SC/ST students to find connection, clarity, and a means to contribute to community members outside of campus.

Before the pandemic, the ASC members taught school-level maths, science, and English at the nearby Rohith Vemula Education Centre. They also fundraised for them and, crucially, taught the organisers at the centre how to best fundraise for themselves. Their work bore fruit when ASC members could not participate in their mutual aid during the pandemic summer, the centre successfully raised funds and resources they needed independently for around 20 to 30 children in Mumbai’s Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Nagar, near the IIT Mumbai Market area.

Despite lacking institutional support, the ASC shares the spirit of Nalanda Academy’s capacity building, the immediacy of the Bhim Army tuition centres and other mutual aid educational initiatives that recognise the revolutionary and transformative potential of what Professor Shailaja Paik terms ‘Critical Dalit Pedagogy’.

Prof. Geetha says, “Babasaheb [was] a point of inspiration to push people to study. To push them, not to give up, you know? It’s, I think, just an amazing experience; it’s something that non-Dalits don’t know about at all…it’s a world that, how can I even explain it? It’s heroic at some level, but it’s so resilient also, right? It’s multigenerational. It goes back to Babasaheb’s own generation, not simply now.

And there’s a continuity which is seldom taken note of in contemporary understandings of ourselves or our times, right?”

Spaces for unlearning

M, now doing her PhD, was one of the few female members of APPSC in IIT Mumbai from 2018 onwards. She signed up for the group because she wanted to continue being involved in campus activism as she had been in her undergrad days. Gender parity is something all of the groups report as hard to achieve due to the abysmal male-to-female ratio in the IITs themselves.

Something that K, an old APPSC member who was a researcher at IIT Mumbai from 2018 to 2019, observed about women in Ambedkarite study circles is similar to Prof. Geetha’s own thoughts. Namely, the openness to dialogue and the space for women and gender minorities to be taken seriously by peers. “I think a lot of unlearning has been done among us,” she says. “Like, we come from a certain privileged educational background, which gave us the opportunity to unlearn what we learned, like what was conditioned in us, right? I think it’s one of the prominent factors where we developed a space to could share our opinions, we could share what we felt,” explains K. Being a part of these kinds of species was important to her as she had been part of the election campaign of Richa Singh, the former and first woman president of Allahabad University Students’ Union (AUSU).

Ambedkarite study circles discuss texts and ideas around gender, feminism, intersectionality, etc. However, contrary to Savarna or liberal feminism’s ideological compartmentalisation, anti-caste thought and work are central to feminism because the superstructure of caste is built on the control and subjugation of women. Babasaheb himself illuminated this ghoul behind endogamy, and so working to exorcise it is almost inherently feminist, if not explicitly so.

According to Prof. Geetha, there tend to be more men than women in the various anti-caste meetings, study circles, political education groups, etc., that she’s taught in. However, she observes that Ambedkarite environments “[have] got a lot more space. Women are listened to better. I wouldn’t say that chauvinism is absent, or sexual tensions. All of that is there…but there’s a certain intellectual openness that is not found elsewhere. Misogyny and gender issues do remain, but openness, intellectual openness, and a general shared commitment to fighting caste are there. It holds the groups together in spite of internal tensions and anger, and questioning. I think that that’s fairly specific and distinct to these spaces.”

The myth of merit

One of the ways that dominant ideologies and casteism collide is in legitimising the dog whistle that is the myth of merit.

Challenging it head on is the natural next step for Ambedkarite study groups in universities that are mockingly called “educational agraharams”, the traditional Brahmin settlements in South Indian temple towns and villages. Historically built on lands that were granted by royalty or nobility to Brahmins who maintained the nearby temples or other such pilgrimage and religious sites, the metaphor is deliciously appropriate.

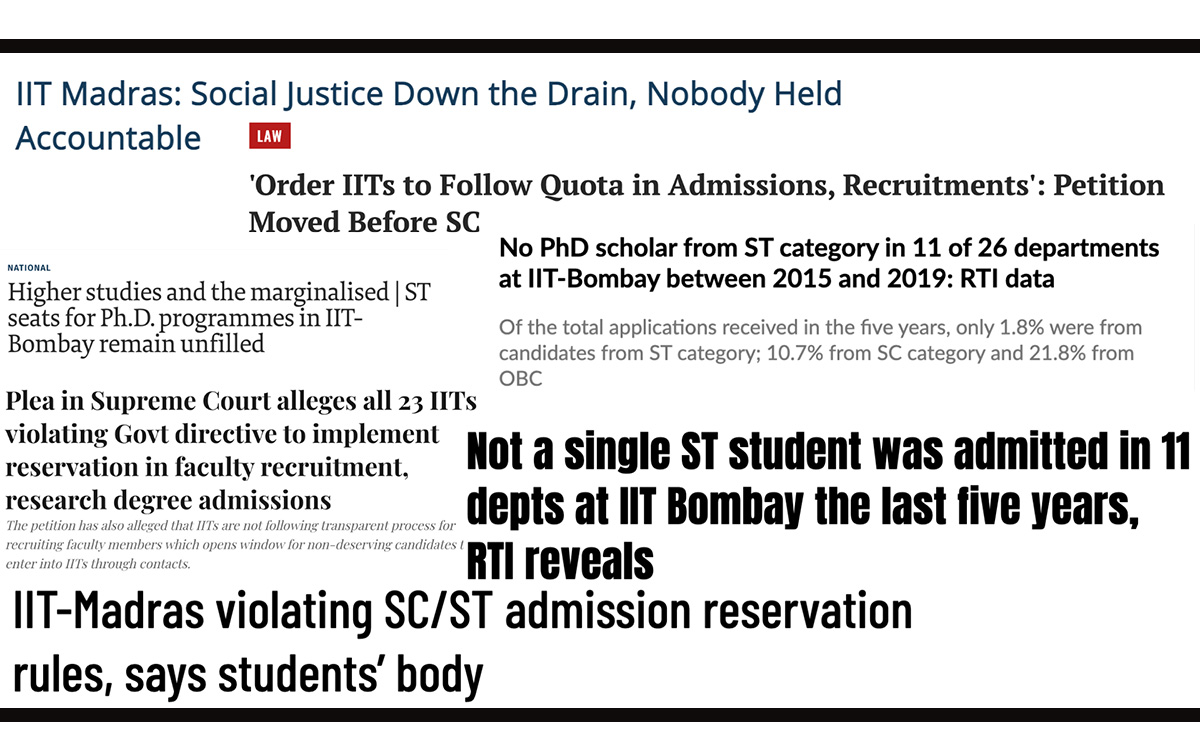

Just last year, a Centre-appointed eight-member committee recommended for the 23 IITs exemption from reservations for senior faculty positions under the Central Education Institutions (CEI) Act 2019. A news report by The Wire notes the irony of this recommendation from a panel instituted to come up with measures for the “effective implementation” of reservations in admissions and recruitment.

“Whenever somebody [brings up the debate of] reservation, I get very angry not because one is opposed to reservation, but reservation works only if there’s background work also, right? I mean, somebody must push children to study and convince parents that don’t take them to work. So who’s going to do that? You know that moral support, intellectual support, networking and keeping tabs on what is available from the State…It’s an enormous amount of labour and fairly difficult labour because you have very few resources,” says Prof. Geetha.

In 2018 when P joined IIT-B, he sent a message to the APPSC Facebook page asking to meet up or join but received no reply. “I joined at a very chaotic time,” he explains. He finally got to meet the members of APPSC at an event they organised where former IAS officer Kannan Gopinanthan was scheduled to speak to the students. P walked away from that meeting as a freshly minted member of the APPSC.

P, a data scientist and self-proclaimed “somewhat introvert”, quickly realised that his predecessors in the APPSC had filed many RTIs relating to reservations in various IITs but hadn’t analysed most of them. He and the few other members who could join remotely through the pandemic took over their operation. They started posting their findings and data analysis posters on all their social media platforms throughout 2021, repeatedly making national headlines.

The APPSC already had the RTI data but lacked the manpower and free time to analyse it. The pandemic provided them with the time they needed, and they made as best use of it as possible. They started with filing RTIs about the state of reservation in IIT-B alone but soon branched out to all the IITs to include faculty reservations and violations of reservation norms at various academic levels in the IITs.

Students and groups from many other institutions have reached out to them for support, tips and advice. “They want to know how we did it, and they want to know how they can do similar things on their campuses,” says P. He explains that filing RTIs, analysing the data and leveraging social media attention to make demands “was strategic and a conscious decision” as it is a blueprint that can be carried out remotely, even with very few members but to significant effect.

The results were explosive and revelatory, and even though the administrations insisted that they had followed the set rules and protocols, the data said otherwise. For example, in IIT Mumbai, not a single ST scholar was admitted from 2015 to 2019 in 11 departments.

The APPSC at IIT Mumbai has also recently created a Caste on Campus website where their RTI data is publicly available. It is open for people to join in on the data analysis— another reflection of their politics.

“Listen, we’re science students,” says P, describing this chain reaction that his collective set off. “We might not have very good design skills for poster-making or even a good grasp on cultural activities, but what we can do is analyse data.”

Becoming of a world problem

The timing was another crucial reason the APPSC’s media leveraging was so effective.

As early as 1916, Ambedkar writes “…if Hindus migrate to other regions on earth, caste will become a world problem”.

In 2020, a Californian state agency filed a lawsuit alleging caste discrimination against the tech company Cisco 2020. The brave (and now-victorious) plaintiff of this historic case whose refusal to take bias from his dominant-caste superiors leads to a groundswell of Dalit tech workers disclosing their experiences of caste-based bigotry that follows them even in the US.

These stories made waves both in India and the US; they are inarguable revelations of how close to the chest dominant caste Indians hold their casteism even so far from home. The landmark CISCO case, in particular, intimately intertwines with Indian institutions not only culture and systemic worldviews as both the brave Dalit John Doe who was outed and the dominant-caste manager who outed him are both graduates of IIT Bombay, bringing more attention than ever to the APPSC.

Like many news outlets, Ambedkarite organisations, anti-caste scholars and activists pointed out, many of the testimonies and accusations from Dalit tech personnel and engineers were pointed at rampant casteism from upper-caste networks cultivated in IITs, transplanted into Silicon Valley.

Facts and stories; stories and facts

Prof. Geetha reminisces, “This person who invited me to Dharmapuri [to give a lecture on Ambedkar’s writings] told me about his first encounter with Ambedkar. Everybody grows up listening about Ambedkar, so reading Ambedkar [isn’t as common]. He said he was inspired to do so by a high school teacher when he was in Class 8. [The teacher] who was a Dalit said go to the local library and read Untouchables and Untouchability. That’s how his journey began.

“So these stories are so precious, right? They chart a fascinating intellectual history of the times [and] of how today you have the study circles and [of the] labour that’s gone into them, the work that’s been there.”

However, the story that haunts A, of APPSC in IIT Mumbai, while looking back at their path is that of Aniket Ambhore. His institutional murder was two years before that of Rohith Vemula—one that split open the nation and brought into the mainstream a roaring blue assertion from the margins.

“We have asked this question in meetings and discussions about why Aniket Ambhore’s suicide never became a national kind of question. For that matter, the other thousands and thousands of people who are getting oppressed, why doesn’t that become a question for the nation? Then, we have to somewhere come up with answers to it,” muses A.

A, in particular, holds that a central physical space for marginalised students would carve out a dimension for safety and support and perhaps help prevent the kind of isolation they are so often systemically subject to. They are currently agitating for a room for the SC/ST Cell, which has still not been granted or facilitated in any constructive way.

They want incoming students to know there is support available and have secured five to 10 minutes during the IIT Bombay orientation program to explain to incoming students the policies against caste discrimination and the existence of the SC/ST Cell. They also plan to create an education module on caste discrimination in academic institutions and caste sensitisation. It will be a mandatory programme for all students and faculty in the 2023-’24 academic year, similar to the gender module administered by the Gender Cell. It will be the first of its kind in India when it is produced and implemented.

The work of generations

From 2020 up to early 2022, of the 23 IITs, Gandhinagar, Guwahati, Kanpur, Kharagpur, Indore, and Mandi have opened research centres on Indian Knowledge Systems. IIT Delhi’s centre now gives two courses dealing with engineering knowledge and scientific concepts drawn from “ancient texts” in Sanskrit.

By contrast, Ambedkarite study circles seem to spring up and grow in the most unforgiving and blighted ground.

The sharp contrast in structural support, legitimisation and informal encouragement for caste-based traditions and any kind of anti-caste education is thrown into focus again and again. Additionally, the structural strangling of opportunities and aid for oppressed groups show just how potent education as a site is.

Speaking of participating in the body politic, M’s time at the IIT-B was brief compared to other students involved in campus activism. Most of it was spent online because of the pandemic. She was part of the initiative to analyse and publicise data from the accumulated RTIs relating to reservations in IITs and compile it on the website Caste on Campus. While she was in the thick of it, she explains, “I have started disassociating success with attaining something. The outcomes are not in our favour, right?”

She continues, calm and considered, “The outcome cannot be the sole criteria for success because there’s so much that goes into organising anything. For example, when we were doing the RTI work, we knew that this might not change the practice of what is going on, bringing up practices that we knew may not change anything. But still, we went ahead with that work; we went ahead with the newspaper reports, because we were like, this is important, right? We might face repercussions also, but that could also happen. But [we] still go ahead with the strength to do something—just to make people understand what kind of reality exists, and just communicate that.”

Arguably, anti-caste student activism, if not Ambedkarite organising in general, is a collective battle to unveil the reality of caste. Ambedkarites aren’t only responding to present-day concerns but through their self-directed education, principled agitation and community-centric organisation. That’s why the APSC is committed to keeping debate alive, despite bleak and arguably impractical circumstances. As to what they aim to achieve through their struggle, S says that “it is continuous, and we have to go on. It’s the work of generations and will take generations to complete.”

Appendix

Something awry in IIT Madras: the whole story – Hindu Janajagruti Samiti

IIT dropped my name from the alumni award list under BJP pressure, claims AAP’s Somnath Bharti

IIT Madras and Modi Government Play Big Brother, Ban Student Group