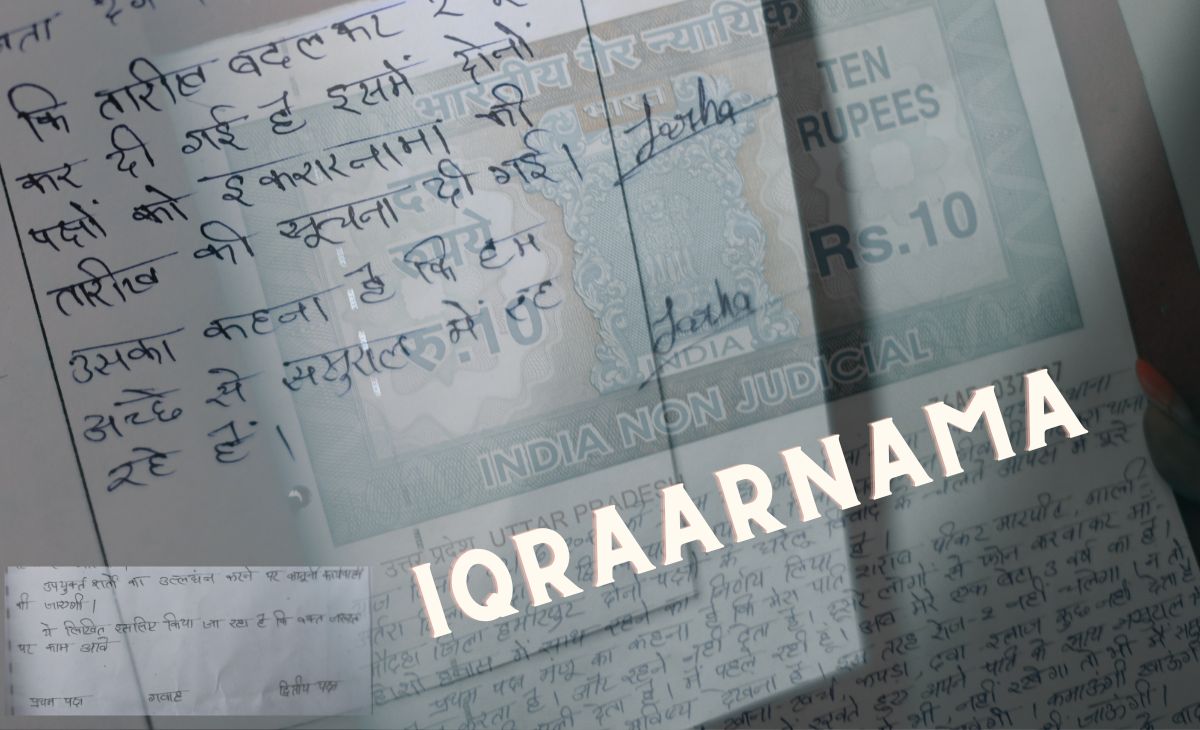

When The Third Eye organised a discussion with three caseworkers from Banda in Uttar Pradesh, we began the conversation with one detail. We had noticed that the caseworkers used the word iqraarnama a lot. The meaning of the Urdu term iqraar is to declare or acknowledge something. The caseworkers use this idea as a tool while negotiating for women in cases of gender-based violence. Clearly, in the perspective of these caseworkers, the creation of the iqraarnama as a document of settlement is quite different from the way the legal system, mediation centres and police facilitate samjhautas. What marks the difference in these two approaches—one where the pursuit of justice centres the woman and the other the family? Read on to find out.

The Third Eye worked with 12 caseworkers in rural and small town Uttar Pradesh, and through a process that included immersive writing, theatre-based pedagogies and year long workshops, the caseworkers became the lexicographers of The Caseworkers’ Dictionary of Violence.

TTE: Here is something we wanted to ask you about. When you facilitate settlements or compromises in cases, you call it an iqraarnama. But when you refer to the ones mediated by the police or by family members, you call it samjhautas. So, what is the difference between their samjhauta and your iqraarnama? What kind of cases do you draw up an iqraarnama for, and why?

Avdhesh: The first thing to note is that we do not undertake any kind of negotiations in cases involving murder, dowry death, sexual harassment, rape or suicide. We only facilitate samjhautas for maintenance cases under CrPC Section 125, or those falling under the DV Act (Domestic Violence Act 2005 under which any woman in a household can file a case of domestic violence against other members of that household), and those under IPC 498 A (related to interpretations of mental or physical cruelty towards a woman, as well as settlement). We take up these cases if people come to us (instead of going to the court).

Pushpa: One kind of compromise happens in courts, police thanas, and wherever these processes of justice take place. The other kind is the iqraarnama [which we as caseworkers facilitate]. There’s a stark difference in the thinking that guides both of them. Because the system wants to save the family at all costs, that is what guides them.

In their eyes, the family is at the centre. But for us, the woman is at the centre. We believe that the woman is the one who gives meaning to the family, and not the other way round. If the woman in the family breaks down, the family ceases to exist.

Other institutions that mediate such compromises are driven by the idea that the family should remain intact, even if it spells ruin for the woman. So, this is the big contradiction between our iqraarnama and what they call a samjhauta.

Shabina: To gain a deeper level understanding of these words, we need to look at the very meaning—the samjhauta mediated by society or the law-and-order system on the one hand, and the iqraarnama that we [as caseworkers] draw up. The word iqraarnama carries a meaning of its own. If we break it down, iqraar conveys that “Yes, I acknowledge that I did these things, and I vow that I won’t do this again.” This iqraar is done after a lot of thought and understanding. This is not a pressure tactic on either of the parties involved. However, when it comes to samjhautas arrived at by the system, there is tremendous pressure to keep the home fires burning. And to that end, everything is fine, in their view. Both parties are told, “You bend a little, and you also adjust a little,” to keep the family together.

Contrary to this, the iqraarnama works on the principle of “I know, and I accept that I have hit her and I have been violent with her. But I won’t do it again in the future.” This is the kind of language and words we use when we write up the iqraarnamas. It serves as a safety net for women. This document holds no legal validity but that is inconsequential in practice. What matters is that it creates a fear in the husband because he has accepted that he has been violent and has stated that he will not do it again. This written acknowledgement is a form of security for the woman. If the husband fails to honour the iqraarnama by reverting to his violent ways, we can use the iqraarnama when we register her case in court.

This record corroborates the fact that at a given point in time, the husband had accepted that he had been violent towards his wife. In that sense, the iqraarnama becomes a record of violence.

If we look at the language used in the mediations facilitated by the system, or pay attention to the language used by the [court-appointed] mediators, you will see that they say things like, “Now this family will live happily and lovingly together. There are no terms or conditions. That is all. The ‘conflicts’ between the two of you are all over now. You [the wife] are not blame-free/not so innocent, and neither is your husband.”

Here, the language used in mediation does not indicate who is the source of the conflict, and who is suffering as a result of the said conflict. But in our iqraarnama, the perpetrator and the person facing violence are clearly identified. This gives strength to the woman. This is also what makes our iqraarnama different. We listen to and understand the viewpoints of both parties, and also bring in our own perspective. We talk to the woman separately to get a full picture. We conduct intense discussions around what the woman wants. Whether, for example, she says, “I want to go back to my in-laws’ house”, or “I want a divorce”, or that “I want to take back my dowry”. So, it’s not as if we are undertaking negotiations that are centred around women ‘compromising’ to ensure they return to their sasuraal. It’s much more complex than that.

Avdhesh: We also draw up other kinds of iqraarnamas, where we have managed to get the entire dowry returned to the woman, and even get both parties to agree to a divorce. If she wants to stay in her sasuraal—which does happen at times—we draw up a duly written iqraarnama on stamp paper that spells out the woman’s terms clearly. We then read out these terms and conditions for all the parties to hear. If the husband refuses to agree to the terms, then we do not go forward with the iqraarnama. It can put the woman in a dangerous situation, making her vulnerable to increased violence, if her terms—which are completely valid and appropriate—are not agreed upon. In these situations, we give the woman about two months to think things over. We pause the mediation. We consider the case closed once the divorce has been finalised and the return of her dowry is successful. But if we are sending the woman back to the in-laws after an iqraarnama, we try to stay in touch with her for a long time and regularly follow up on her case. During this time if she faces problems at her sasuraal, we speak to her natal family and bring her back to their home and arrange for a trial in court. In all of this, the woman is always the priority.

If the woman says, “Didi, I want to return to my in-laws,” we counter that with our own questions. “Why do you want to go there?” What are her reasons?

Shabina: Sometimes we tell the woman point blank that if you were to return to your in-laws, you might get killed; that if you want to return under pressure from the community, you may do so. We can no longer accompany you or support you in this samjhauta, because we can already see a bleak future. After going back there, you might be subject to such torture that you might not be able to come back. We tell her that we are closing your file in the organisation. If you want to return to your sasuraal, you may do so with social or familial backing [but not ours].

The seriousness of the cases is also a factor in mediation. Supposing we are aware that the woman is being subjected to a lot of cruelty, but there are no children in the picture. Then we know that there is one less factor to hold her back. We are also well aware of the nature of court proceedings, as well as the fact that Section 125* amounts to nothing substantial. We may be able to make an educated guess to say that the dowry is possibly intact. This woman then, after a divorce and the return of her dowry, could lead her life on her own terms, whether alone or with someone. She could get married again. In this way, we look at all the options to see how the woman may be benefitted.

Compromises in the system are dealt with on the basis of numbers. Family courts, thanas and mediation centres like to boast that “today we mediated these many compromises”. However, we don’t keep score. What we focus on instead while drawing up an iqraarnama, or while arranging for someone’s dowry to be returned, is to ask why we are doing it? How does the woman stand to benefit from this? We think from the perspective of the woman, and let that guide our actions.

We do not nitpick. For example, if there is a small part of the dowry that is not returned or a small amount of the entire mehr is not given; or if in the case of a Hindu marriage only the dowry is returned but no other compensation is given to the woman, we let these things go. This is because long and dreary court cases will drain the woman’s mental energy. It will keep her from thinking about her future or work. She will have to keep trudging in and out of court. Considering all of this, sometimes we have to make adjustments. In terms of money, we tell the woman and her family that “you are getting this amount, it is better to take it and put an end to this issue once and for all”.

Avdhesh: We are aware that these iqraarnamas have no legal value, but we still strongly validate them. We often tell the husband and the sasuraal, “Do not remain under the impression that this has no value.” And they do accept it, and get intimidated by it. After the iqraarnama is drawn up, there are many families who tell us, “Didi, you people did really well by my daughter-in-law or for my son.” They feel proud and they come to us and express it.

Shabina: The impact and fear people in our society feel when we draw up an iqraarnama can also be explained by our image, by what we stand for. Everyone can see that we are constantly advocating for justice in courts and the legal system. We have handled cases of murder. We have handled cases of dowry deaths. We have also sent people to jail for rape. So that fear factor establishes itself where people think that “Yes, these people handle such cases, so if they are preparing a document, it might be used against me.”

We have been able to carve out an image for ourselves which says, we don’t stand for wrong, we don’t support wrongdoers. Maybe, this image also differentiates us from the justice system?

Translated from Hindi by Pakhi Pande with inputs from the TTE team.