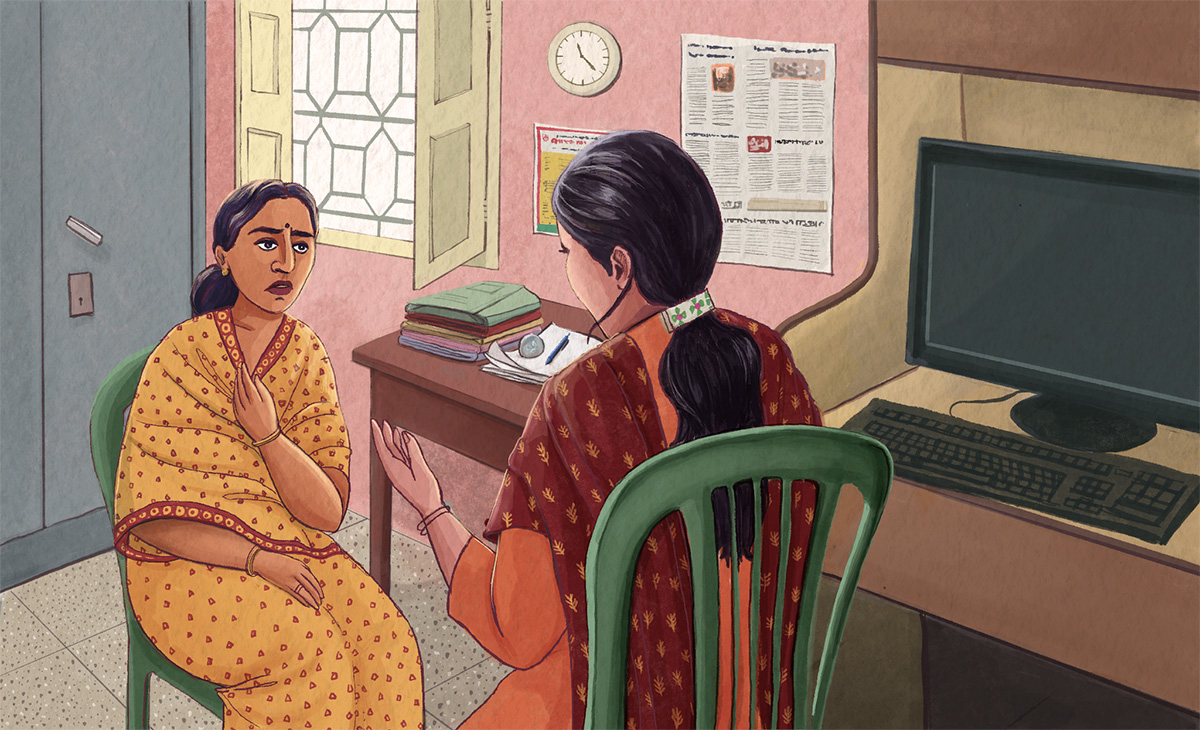

What does it mean to counsel a woman while centring her needs? At the time of taking a decision, a woman finds herself caught in a complex web of social expectations that she progressively frees herself from. Many questions stand in the way of making a decision: Where will I live after separating from my in-laws? What will I do? How will I raise my children? How will they claim their father’s name? What will the community say? For every woman hemmed in by these questions, there is her caseworker who undertakes a lengthy struggle to help her arrive at a conclusion. Even though reaching a decision takes time, it is not long before the process of counselling begins to affect some changes in the woman.

Read on as a caseworker from Vanangana, Banda, Uttar Pradesh, takes us through a case where a woman came to realise some valuable things for herself, through counselling.

The Third Eye worked with 12 caseworkers in rural and small town Uttar Pradesh, and through a process that included immersive writing, theatre-based pedagogies and year long workshops, the caseworkers became the lexicographers of The Caseworkers’ Dictionary of Violence.

During the process of counselling, efforts are made to help a woman recognise her own strengths and talents. A major priority is to make her conscious of her labour, and to provide her with a set of options, complete with a list of costs and benefits to weigh them against. We first survey the kind of livelihoods that are viable in her area and then encourage her to find work there. We tell her, “All day and night, you work at home for your family with no returns. If you work outside of your home, you’ll be able to earn money and build a life for yourself.” We encourage them to either open a shop, or do daily-wage labour, or work even in male-dominated places like brick kilns. In the course of this exercise, a woman often breaks down, gathers herself, works through her anguish and cries out in distress. “I did so much for both, my own family and my in-laws, but no one stands by me today. If only I had done something for myself instead of the labour and all the sacrifices I made for these people. Perhaps they would have given me some respect, even if it was driven by their own selfish reasons, this very family that is denouncing me today.”

How central is the question of labour in encouraging women to make decisions about their lives is evident in the case below. Ten years ago, Usha (name changed) of Chitrakoot district got married while still a minor. Right after the wedding, issues cropped up with her husband and her in-laws. Her husband gambled and made kachchi sharaab (homemade hooch) at home for his own consumption and sale. He tried to compel Usha to brew the liquor too, and every day her refusal was met with violence. Whenever the brutality escalated, Usha’s father and brothers would take her away for a few days, and then send her back to her in-laws after coaxing and cajoling her into submission. Usha found herself shuttling back and forth between her maternal and marital homes. Her parents were poor, and her brothers did not give her any money. Usha would do mazdoori – manual labour – to sustain her husband’s family when she was there, and also supported her natal home through mazdoori. Despite her efforts, she was taunted time and again by the men in her maternal family, and often suffered violence at their hands. “We do not want to eat from your earnings,” they would say, and send her back to her in-laws.

Between all this, she gave birth to two children. As for the violence, there was no end in sight. Instead, it grew, and the children too were affected by it. Seeing no other alternative, Usha’s parents filed a case against her in-laws at the Karwi District Court under Section 498A pertaining to dowry harassment, and Section 125 to claim an allowance for maintenance.

Usha’s case had come to the notice of the organisation about four years ago, and the process of counselling started with her immediately. The police, the court, our organisation, everyone mediated a set of samjhautas. Usha accepted all these samjhautas and returned to her in-laws time and again since, at her maternal home also she suffered mental and physical violence, as well as barbs by the community.

Between her in-laws’ and her parents’ homes, our counselling continued. She was still convinced that a woman only has two homes to call her own: her husband’s or her father’s.

It took her a long time to recognise, through counselling, that she was surviving on the strength of her own hard work, and could continue to do so without the crutch of her husband’s or father’s name or shelter.

Finally, in 2020, Usha took the final step of returning to her parental home with her children. To her family, she said, “I won’t be dependent on you, I will stay here and raise my children on my own income. If someone bothers me, I will rent a house and stay there on my own, away from you.”

Presently, she runs a bisatkhana store from her parents’ home, selling trinkets and jewellery. The store is doing well. She is able to get by comfortably with her kids. She dreams of earning enough through her shop to be able to build her own house. She dreams of running her shop from her very own premises, and of living independently, free from the clutches of violence.

Clearly, the role of counselling is to make a woman conscious of the value of her own labour. The moment she understands this, she gains strength and is able to give a fitting reply in the face of violence.

Translated from Hindi by Pakhi Pande with inputs from the TTE team