Dr. Priyadarsh Ture has worked on community health with rural and Adivasi people in Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh and Odisha for over a decade. As a doctor, he has volunteered his services during multiple crises and disasters, including the Kedarnath and Kerala floods. During the migrant exodus last year, he was at the border of Chhattisgarh, helping migrants and their families cross over and reach their homes in Jharkhand, Bihar and Odisha.

Dr. Ture volunteers with the YuMetta Foundation and has been working with Shaheed Hospital in Chhattisgarh since 2019. In his interview with The Third Eye, he shares his insights about decentralised and community-driven health models and processes.

Take us through your work with Shaheed Hospital. What is the vision and how does it work within a community health model?

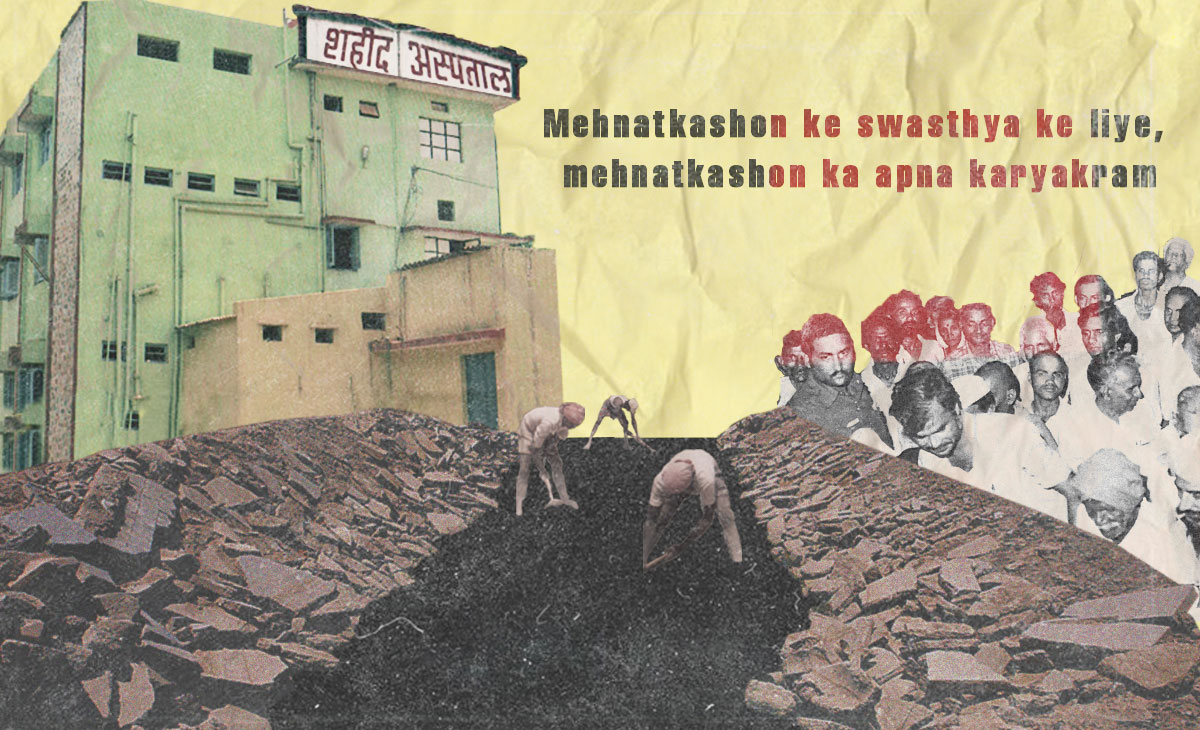

Shaheed Hospital was built in 1983 – quite literally – by labourers and the working class who were employed at the Bhilai Steel Plant in Balod, Chhattisgarh. Mehnatkashon ke swasthya ke liye, mehnatkashon ka apna karyakram – it is a hospital for the workers by the workers. It was a long-held dream of the late union leader, Shankar Guha Neogi, who imagined an affordable public hospital for the toiling masses. He had also contributed to building more public infrastructure for education, literacy, de-addiction and health. The hospital has been providing ethical and affordable treatment not just to the mineworkers of Dalli Rajhara but also to the people of nearby villages of Balod and the Adivasi community for the past 25-30 years.

We have been part of the broader health movement and have provided affordable, ethical, equitable treatment and health services to our people, rejecting commercialisation, and resisting the infiltration of Big Pharma and corporations. We get about 150 patients a day who are looked after by a highly qualified and trusted group of doctors and health workers.

We actually have a very unique history with respect to the health workers in our hospital. A lot of them earlier used to work in the mines – they were specifically trained by doctors to work in this field and they voluntarily got involved in the hospital’s day-to-day functioning.

While some manage accounts, others act as health communicators with the patients, breaking down medical terminologies and instructions to them in a simple manner, in their own local language.

We actually do not need external funding to run Shaheed Hospital. One hospital bed costs Rs.10 and our patient load is so much that it covers our costs. Some of the costs are also reimbursed through government health insurance schemes. Even for people not enrolled in such schemes, the costs for treatment are not very high. For example, a normal delivery costs Rs.1000, a caesarean around Rs.5,000. Even the costs of the most complicated of surgeries don’t run beyond Rs.15,000.

So you are saying this is enough to run a hospital? I am asking again because most private hospitals in cities do not charge less than Rs. 30,000 for a delivery.

If you look at the history of how this hospital came about – the workers who built it would work in the mines during the day and construct the hospital at night. They even contributed to the costs by donating a part of their salary every month. Even today, our trust members comprise mostly workers and mazdoors and they maintain that the hospital would only serve the poor and working-class people in the community.

There has been no change in our financial structure, and neither have we increased the costs of OPD or any other treatment. Plus, we get reimbursed from government insurance schemes as well, so there is no need to charge exorbitant amounts from marginalised people for their right to basic healthcare. Sometimes we do face a financial crunch, which may lead to delay in salaries for a month or two but that’s about it.

Today, we are able to serve so many people from humble backgrounds across a 100-km radius from our hospital and provide all kinds of health facilities from obstetrics, dentistry and paediatrics to surgery, gynaecology and medicine. We also house the ICTC centre under National AIDS Control Organisation and a DOTS centre for tuberculosis. Our various interventions, especially in sanitation and community health in bastis, have inspired youth to volunteer with us, especially those who seek out alternative models of development.

How did you develop an interest in studying community medicine?

Community medicine is one of the most important subjects taught to us in MBBS for about three to four years but it is often ignored. We are taught ways to understand the problems and the needs of the community, the interventions that can be made, and whether these interventions have been helpful in improving health indicators. We move beyond a pathological approach to also consider social indicators that impact a community’s health.

When I was working in PHCs in rural and Adivasi areas, I realised that a clinical approach is not sufficient to bring about long-lasting and sustainable change in health indicators; hence I chose to specialise in community medicine in my post-graduation.

In your experience of working with Shaheed Hospital, how has your understanding of public health come about and how has it evolved over time?

See, public health is a very broad term. I particularly define it as a mechanism where every single person, especially from the most of marginalised communities, every last man standing in the most remote of locations, receives help. And not just help in the materialistic sense, but holistic help where there is no resource constraint.

As a taxpayer, one shouldn’t be thinking that only those who have money to get treated should have access to healthcare services.

Healthcare is a fundamental right and public health systems should cater to everyone, irrespective of class, gender, caste or religion. The public health system should have the capacity to maintain all kinds of checks and balances as well as be resilient enough to absorb shocks like the Covid pandemic.

In India, I don’t think we can call public health a reality. Ever since Independence (and even prior to that), many national-level commissions have given very important recommendations to manage public health to increase the system’s capacity, to stop the emergence of private players. To ensure setting up of PHCs with capacity of at least 50 beds, to have 2-Tier hospitals with a capacity of 600-700 beds, to have 3-Tier hospitals with a capacity of 2,500 beds. In addition to meeting infrastructure demands, these recommendations would have also ensured that all our human resources – doctors completing their MBBS for example, would have been automatically absorbed into this system and there would have been no need for private players to step in to recruit them. But all these commissions came and went without any of their recommendations being implemented. So even if there are PHCs, they are crumbling, have no doctors, and also lack medical equipment. One is not able to find a doctor or a hospital for kilometres at a stretch in rural areas and private hospitals are rife with malpractices.

Public health in India is affected by multi-level problems. Recently, some policy recommendations were in the works that would link district hospitals to private players to give “quality service” but no one seems to understand that capitalism is market-driven and favours profit. The people who were able to afford treatment at these district hospitals will again be left with no option other than to pay through their nose or not avail private healthcare services.

What would you say is the relationship between rural Adivasi communities to their health, their mortality? Is it different from what you may have observed in urban spheres?

I think rural and tribal communities are more prepared for death than us at an emotional, psychological level.

This could either be because of their outlook towards life or they have become used to witnessing far more deaths at close quarters in their communities and families. This also arises from a sense of hopelessness and helplessness as a consequence of healthcare being a secondary or tertiary issue in rural areas. People also have more faith in quacks and traditional doctors, and won’t take an ill patient to a hospital unless he is on his deathbed. The saddest part about all of this is the sense of resignation that has set in. People are not angry enough about why they are being denied health services, why their family members are dying of medical negligence and why doctors refuse to touch and treat Covid patients in PHCs.

Why is there no anger?

The poor man has been made to believe that it is his fault for not bringing the patient to the hospital on time. He is made to internalise that getting admission in a ward or getting minimal access to oxygen is a privilege; he has been denied the understanding and knowledge that access to oxygen and healthcare is a fundamental right.

I think health has never been a priority in any of our movements, historically. For tribals, the fight for their right to land and jungles has been a priority; for Dalits, self-respect and fighting caste discrimination has been important. Understandably, health could never be a central demand, which I feel is changing now, as the nature of political movements is evolving post-pandemic.

More than 60% of people in our country do not have insurance cover for health, which is a lot. I am hoping we can make this an electoral issue in the next general elections and demand for better health services in a more revolutionary way.

What are some of the community health models and strategies that have worked in the pandemic, according to you?

Mostly it is the decentralised model that has been the most successful, where the stakeholders work along with experts to improve the community’s health. Some of our senior doctors have been working with tribal health initiatives in Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh during the pandemic where the gram panchayats have taken up responsibility and set up a system to monitor who is in isolation, who will support symptomatic patients, what kind of support the health workers and doctors will receive, etc. Information dissemination has also been systematically done, wherein people are aware of what numbers to call in case of an emergency and where certain medicines can be procured. In Maharashtra, gram panchayats have got into action and have handled the pandemic in a very decentralised way, which has prevented cases from rising in certain areas. There has to be interdependency of local governments and the community.

Capacity building is something that should have been done on a priority basis but what we are seeing instead is the government investing money on band-aid measures, which makes it look like it is doing something phenomenal. For example, they would buy two ventilators for a hospital (without training anyone on how to use them), get photo-ops done and the media would sing praises about how effectively they have handled the crisis by buying a couple of concentrators or ventilators. But the same money could have also been used to train and build the capacity of an entire village or town.

Could you share some examples of capacity-building exercises and trainings that you have been a part of and that can be undertaken on a wider scale?

We have been in talks with district administrations in Chhattisgarh to roll out some pilot programmes at the village level through our foundation. We have observed that in the second Covid wave, the patients were unable to reach the hospital on time because they were unaware of how quickly their health was deteriorating at home. And it became difficult to save critical patients when they are finally brought to the hospital, because it is already too late.

So, we have made a screening tool and trained ASHAs (Accredited Social Health Activists) to use it. The screening tool consists of an oximeter and six-minute walking tests, which will determine the status of a symptomatic Covid patient. If such patients fall into the red zone as reported by the ASHA, they are immediately referred to the nearest PHC or hospital, where doctors have been trained on how to handle such cases.

The PHCs have been equipped with oxygen cylinders, concentrators and medicines and the doctors have been trained on how to administer Covid treatment. In case the patients’ condition still deteriorates, they will be referred to an SHC or a CHC where their health status is regularly monitored. If they still do not show improvement, they will be referred to the district hospital.

We are trying to connect and build linkages between the village and the district health systems and set up local helplines to facilitate early detection and early treatment of Covid patients and save more lives. We have been able to implement this model effectively and it has been showing results; so in case of a third wave, we are hopeful we already have a model in place.

Recently, the Chhattisgarh Government announced grants for industries to set up private healthcare services in villages. How would that impact communities and their health?

Thankfully, it has not been finalised yet and activists, civil society and political organisations have protested and demanded its rollback. So, there is still a chance of it not materialising. But nevertheless, such a move would be disastrous for people here. The private sector has never assured affordable and equitable healthcare.

The existing public healthcare services will become more costly, and there is a possibility that people in the middle and lower middle-class strata may slip below poverty line considering the economic crisis has worsened post the pandemic.

As someone who has worked with tribal communities for years, what would your advice be to policymakers?

What I dislike about the policy landscape is how people’s health and lives are reduced to the complications of finances and jargon, and how we waste so much time in bureaucratic channels without realising lives are literally at stake.

We keep on hearing “We shall be TB-Free”, etc., but no one comes to the grassroots to check how all of these policies are panning out and the kind of corruption that exists. Listen to what your ASHAs and Anganwadi workers are telling you about community health and increase their wages instead of bringing in new policies that are far removed from reality. It is really like going back to the basics.