Among these letters, there is one from Sukhbati. Sukhbati, in her late 20s, was from Kushmadh village, Mehroni, and came to a women’s literacy camp in Lalitpur back in 2003. Nirantar had just started working in Lalitpur district on women’s literacy and empowerment. Within a year, we had started feeling that we needed to organise a residential literacy camp because women didn’t have the time to come to the village literacy centre regularly. The women had told us that in the midst of all their work, it was difficult to set aside two or three hours every day to learn reading and writing. Nirantar had already successfully experimented with the residential camp strategy with rural women in Chitrakoot and Banda districts in the ’90s where they were able to give time and attention to their learning and acquired literacy skills. We set out to organise a 10-day camp for the women. After about six months we had a list of around 40 who had shown an interest in the camp. Sukhbati was one of them. She had some schooling already. We wanted her to come to the camp to strengthen her skills and eventually recruit her as a teacher at the literacy centre. I got a real sense of Sukhbati’s literacy level when I read her letter aloud in the general assembly at the camp.

I remember that moment vividly. I picked up Sukhbati’s letter and read:

“Didi! My younger sister is being married off to an old man. She is 15 years old.”

I stopped, trying to make sense of what I had just read out loud. I read the letter again. Aarti (my colleague) and I looked at each other. We felt like something had to be done. We took Sukhbati aside immediately and spoke to her. Then Meena and I set off to the village to stop the wedding. We weren’t just unsuccessful; we had to make a run for our lives from angry villagers.

This happened in 2003. I had been working on women’s education for barely a year. My understanding of women’s literacy was not greater than an average person’s. I, too, felt that women need to be able to read and write so that “they can read the bus route numbers and help their kids with their homework”. At a Nirantar training workshop there was a discussion around the goals of women’s education and how it can be empowering for them because it helps give them a voice and a sense of self. I wasn’t sure I agreed.

But as soon as I read Sukhbati’s letter I understood, in a flash, what a big deal it was for quiet, little Sukhbati to reveal what was going on in her mind in just two or three written lines. The letter gave her a way to say something she couldn’t say out loud. The space of a feminist literacy camp also helped her gain faith that she would be able to reach out to us and some sort of steps would be taken. When Meena and I got back to the camp, having escaped the irate family and community members I saw a sense of calm on Sukhbati’s face. Her expression seemed to suggest that at least I tried to do something.

Sukhbati never asked us why we were unable to stop her sister’s wedding. What was important for her was that she had been able to tell us about the crisis she was going through and the letter made this possible.

Her letter-writing marathons would go on till two in the morning.

Sometimes we would scold her, “Go and get some sleep, you can continue writing tomorrow.” But Anita kept at it. Her letters were never shorter than two or three pages. Each began with an invocation of Santoshi Ma or Ma Sharada and ended with the names of all the didis who taught at the camp with a formulaic apology just in case she had done something wrong.

Anita would write about her husband and his violence towards her. Often, we wouldn’t read her letters aloud in the general assembly. We would just say that she had written a very long letter and that we would discuss it with her later. Through her letters, we discovered that the husband used to beat her terribly, that he was not literate, that she was from a well-off family, that her in-laws were poor. We learnt that even two square meals were not guaranteed. Anita was so thin and fragile that we worried that the next time her husband hit her, he might kill her.

When Anita was due to come to the next camp, her husband attacked her with an axe. Her knee was badly injured. She still came at the camp. When we saw her condition, we decided we had to talk to her husband. Anita was terrified by the idea. She said she knew that her husband would beat her when she returned from the camp. Because she forbade us, we didn’t go to speak with him. We kept talking to her about not accepting this violence as a given.

She would listen to us quietly. Then clutching her two-year-old to her chest she would get lost in writing her letters. Her literacy was better than the other women in the camp. During the day, in the literacy sessions, she worked on improving her skills and at night she busied herself with writing letters. Letter writing was like therapy.

She wrote so much her pencils quickly reduced to stubs.

“Didi, for a moment my heart becomes lighter with writing!” she said.

While Sukhbati had turned her letter into a means to elicit action, for Anita it was a way of lightening her immense burden.

Women’s letters begin with invocations of their religion, caste or community.

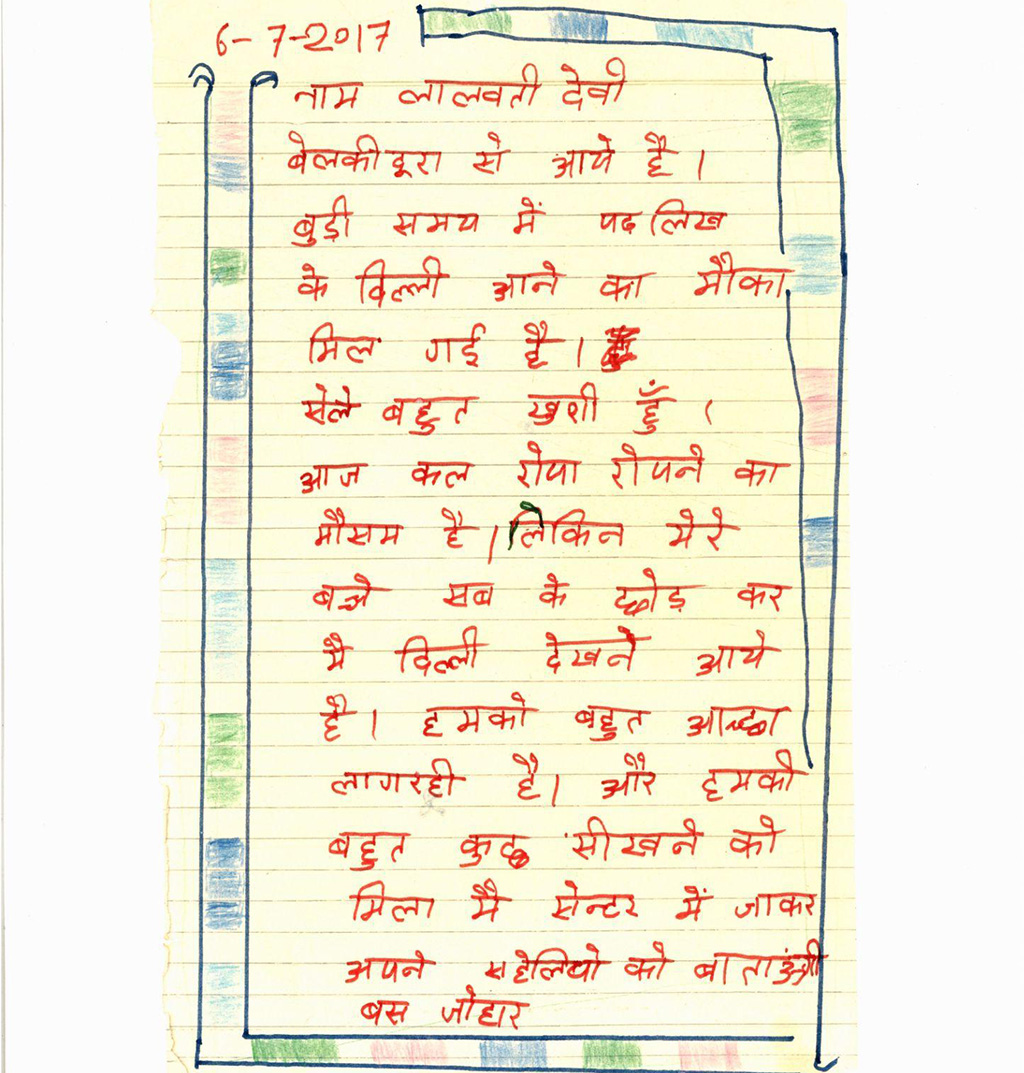

The salutations of newly literate women are different from the ones commonly seen. They usually begin by mentioning the deity of their community—Santoshi Ma, Karoli Matha—and the customary dua-salaams. But when we began working in Jharkhand the women there addressed us and greeted us by saying, “Hul Johar!”

We got a letter like that from Joba Mardi, also from Jharkhand. “…In my field, the paddy crop is ready. After that the paddy is cut and bound. Then the bullock cart is brought to the fields. Then the harvest is threshed in the miseem (machine). Then the fan blows the harvest clean. Then the rice is flattened and then we make pitha for our guests.”

The content of Joba’s letter is the stuff of her everyday life, just one of her many million tasks, the constants.

Between labouring at home, in the field, and at worksites, their palms had hardened and the lines were worn. Gripping a pencil didn’t come easy.

Sometimes they would say, “What are you going to teach us at this age? Give us a sickle and we can reap a whole field in two hours. But even after two days at this camp we are not able to write our names. The pencil is just slipping out of our hands!”

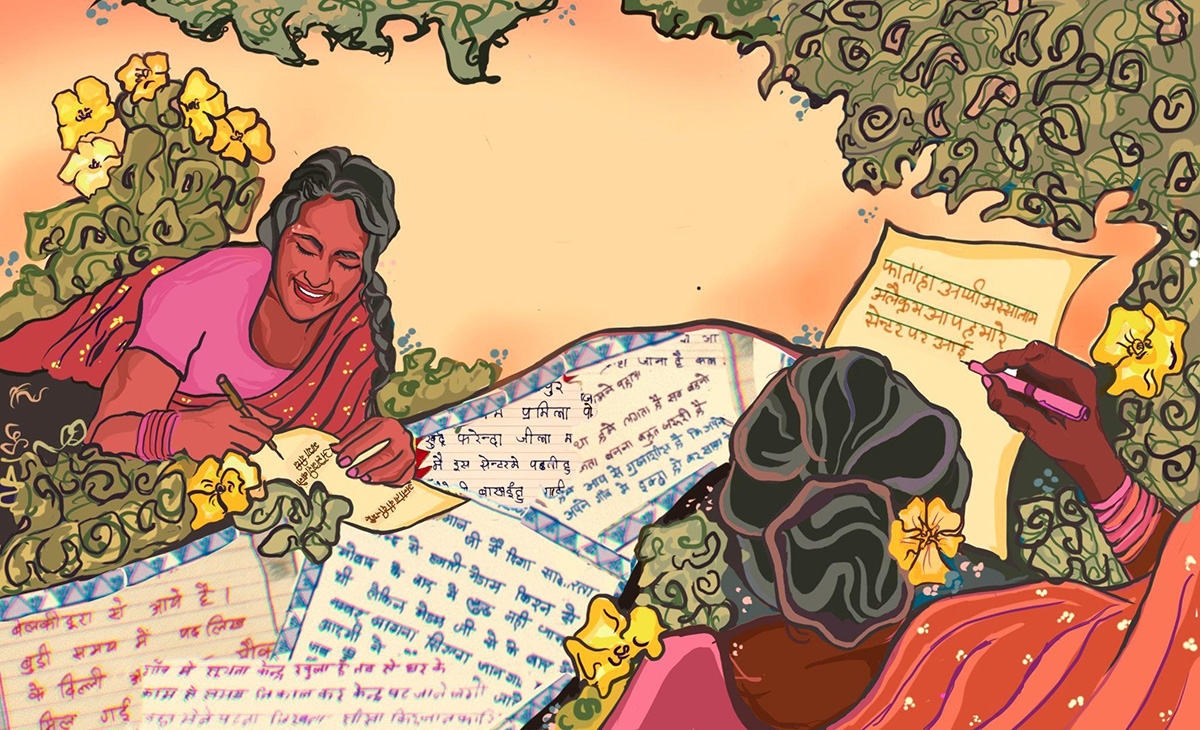

But the teachers at the camps would stay on the job—teaching women, getting them to hold a pen, to practise writing—and in this long process, letter writing was a miraculous tool.

In these letters, something that always struck me as special was the women’s choice of language. It was always ordinary and very clear. No one worried if there was a matra missing or the spelling was wrong or if a sentence was incomplete or if the words were ‘pure’ Hindi. Usually, the letters were written in a mixture of Hindi and their own language. They wrote as they spoke. They never worried about anyone making fun of them for how they wrote.

Lakshmi’s letter was a reflection of this unabashed writing. Lakshmi, about 17 years old and a resident of Semarkheda village, had come to study at Janishala, a residential school for Dalit and Adivasi girls in Mehroni, Uttar Pradesh. (It was a Sahajani Shikhsa Kendra intervention.) At Janishala, we used to organise exposure visits to Delhi, Agra or Jhansi to deepen the students’ knowledge of history. Lakshmi was part of the first trip to Delhi where we went to the Nehru Planetarium. There, as soon as the session started, Sunita’s two-year-old daughter defecated. Lakshmi wrote, studiously,

“When the karyekaram began we felt scared. Then they started showing nice pictures. Some girls fell asleep. Just then Sunita’s daughter pooped. Sunita slapped her and she bawled loudly.”

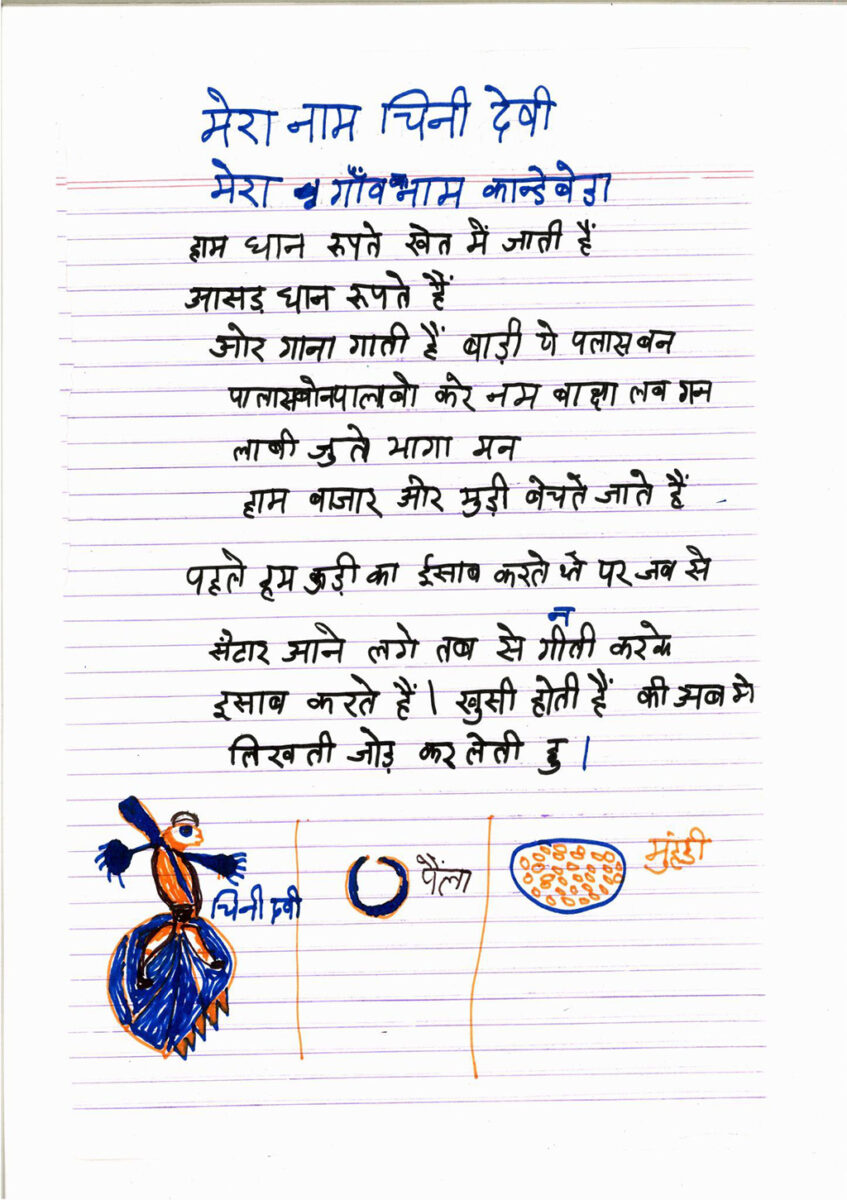

And while we are on the subject of language, it is impossible for me to not mention Gyasi and Halli from Lalitpur and the women of Jharkhand. Like Anita, Gyasi was in her early 20s, and came from Khatora village, Mehroni. She was literate and had come to the camp to strengthen her literacy skills and knowledge. Whenever Gyasi, six months pregnant, grew tired of sitting upright in class, she would lie down and continue writing in prone position. She mostly wrote about what she was learning at the camp and would thank all the didis teaching there. But her language was peppered with Bundeli. In her letters ‘namaste’ would be ‘nabaste’ and instead of the Hindi word for time – samay – she’d write ‘taym’. In Lalitpur, for instance, ‘na’ would often be replaced by ‘la’. So, the name Neelam would be Leelam. And usually the sounds ‘ba’, ‘va’ and ‘bha’ were interchangeable.

But matters of language were not always easy.

There’s a constant push and pull between mainstream conventions and the everyday spoken language.

But when it comes to language teaching, it is the mainstream language that is taught and local language is neglected. Those who come to study also want to learn the language of the mainstream because that is assumed to be the language of the genteel and cultured. But however hard they try, the language of the students is coloured by their mother tongues. The politics of language is amply demonstrated in an incident with Halli.

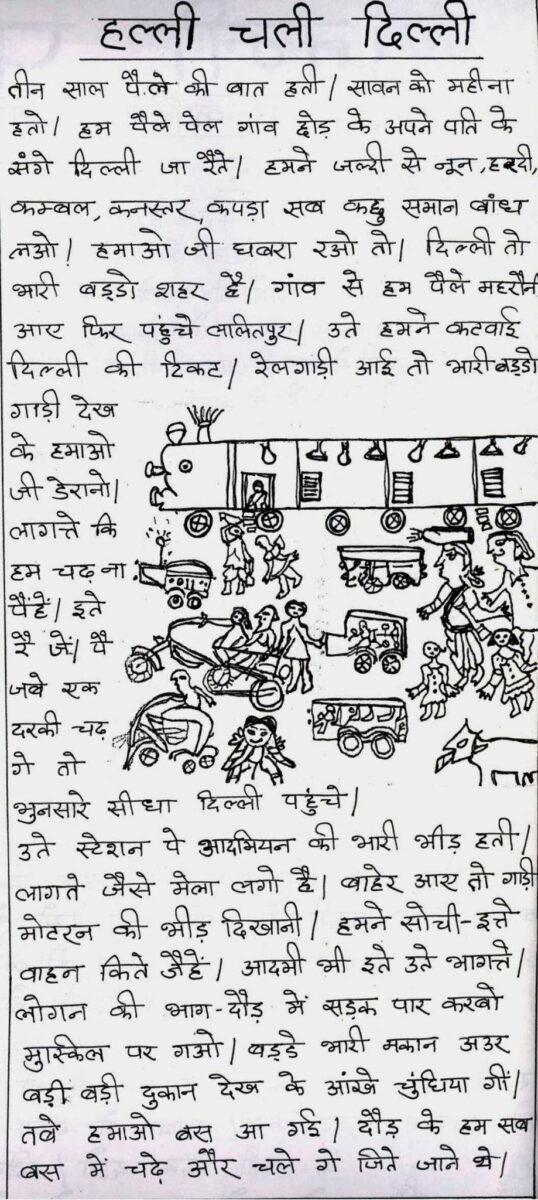

I can see Halli’s face even now when I remember her narrating the story of her trip to Delhi and how she caught the train. Halli, in her mid 30s, was a nonliterate learner of the literacy centre and came for the Jani Patrika workshop from Pathrai village, Mehroni.

Halli was narrating her Delhi visit with such delight that we told her to write it down immediately. She laughed and said, “I only know Bundeli and I will write in that.” We told her to go ahead. But when I read the story, it was written entirely in Hindi. I said to her, “You told me you were going to write in Bundeli?” Halli said, “This is what you taught me to write. How can I write in Bundeli?” I laughed at her response and then she and I joined hands to write her experience in Bundeli. But what Halli said forced us to think. She was right. All the books were in Hindi. Was it possible for us to change our pedagogy? After this we did change our books and our training methods to make the local dialects the centre of language pedagogy.

They were challenging us, the ‘educated’, to read their language.

In terms of literacy, letter writing allowed the educators to gauge the progress women were making in different skill sets. If they seemed to be having difficulties with any symbols, words, sentences or the alphabet itself, we’d address those gaps in the next session and make them work on it. Also, if the women had written about things in their letters they had not been able to discuss, they had the chance to hear their letters read aloud and possible stratagems discussed.

Sharda’s (Simirya, Madawara block) letters bring all this to the forefront. Sharda was around 14 or 15. She used to go to school. When she heard about Janishala she thought it was a better choice and went there for eight months. Because she had good reading and writing skills, she would write five or six letters a day and each one addressed to a different teacher. In a letter addressed to me, she wrote,

“Purnima Didi! I have come to study at the Janishala with great effort. I have paid the fees at Janishala with the money I made from selling the wheat I harvested. I want to study further. Please never send me away from Janishala.” And after that, Sharda’s parting note was a poem. “Red chilli, green chilli, the chilli is so hot. Didi looks so innocent but she is very sharp.”

In that one letter, Sharda had written about her situation, her desire to study and her fear that she wouldn’t be able to. She felt that if she managed to stay on in Janishala after the mandatory eight months, she would be able to study further. Perhaps that letter ensured that strategy. Janishala acted as her hostel until she completed Class 10.

This has also happened because women’s literacy was designed from a feminist perspective and at the literacy centres the women’s context was always kept in mind.

Things often attributed to women’s ‘fate’ and ‘destiny’ were opened up. I remember when we read the story Beta Kiska? Jaleb used every letter of the alphabet and symbol she had learnt to pour herself into her letter. “Didi! My husband has thrown me out of the house and has kept my son with him. He says, ‘You are a hick. You are uneducated.’ But the truth is that he is having an affair with his sister-in-law. I am fair. I have hair like gold. But I am uneducated. I will become educated and send him a letter.”

This is a story from nearly two decades ago when mobile phones and the internet were not so common, and letters were the only way to send messages to remote areas. Back then, when we asked women why they wanted to learn to read and write they usually had two or three reasons: “Jobs might be difficult at our age, but we want to be able to read bus numbers.” Or they would say they don’t want to get cheated if they sell something in the market. Or if they had trouble at their marital home, they would be able to write to their parents. Were women able to do this? Are they able to do this now? It is still a big question. But at the literacy camps and the centre, women and teenage girls wrote and wrote and wrote letters.

They have also deployed letters to assert their rights and power.

Prasasan [Note: Should be written as Prashasan, but since there are slippery slopes between S and Sh, many rural women write this word with a mere S]

Chirai Village, Varanasi

I humbly request that the drains in my village be cleaned. They are not being cleaned right now. I, therefore ask that you please organise the cleaning.

Yours sincerely,

Taradevi,

Prahladpur, Varanasi

Lakshmi, in her early 30s, from Mehroni, writes:

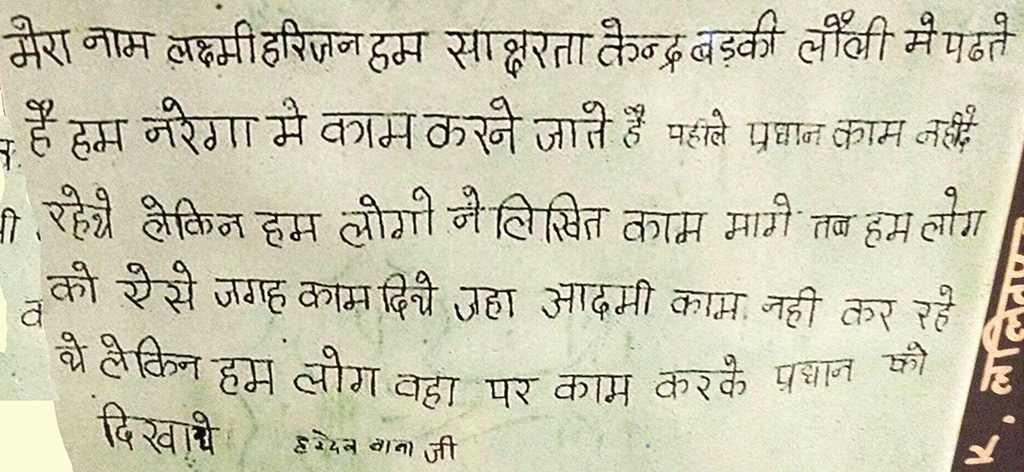

“My name is Lakshmi and I study at the literacy centre in Badkilolli. I do MNREGA work. Earlier the pradan wouldn’t give us any work. But we put in a demand for work. Then we were assigned work in the kind of places where no one was working. But we worked there and showed that pradan. Hardev Baba Ji.”

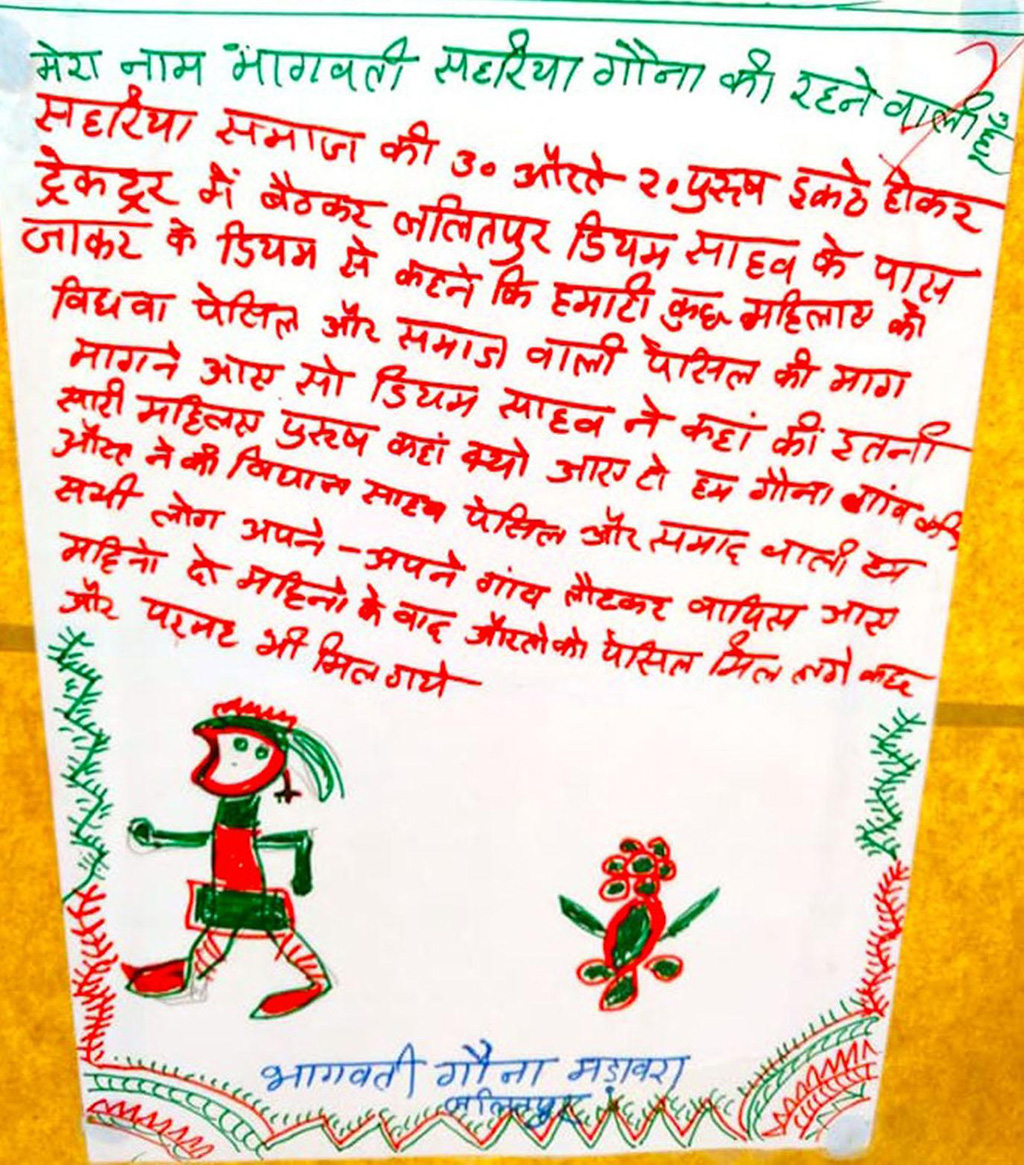

Bhagwati, from Gauna village, Madawara, writes:

“My name is Bhagwati Sahariya and I am a resident of the village of Gauna. Thirty men and twenty women got on a tractor and came to Lalitpur’s DM sahib. They wanted to ask about widow pension and social pension on behalf of some of the women. The DM sahib asked, ‘Why have so many men and women come here?’ … We returned to our village. In a couple of months all the women got their pension and some people got their permits too.”

Translated from Hindi by Nisha Susan and Dipta Bhog.