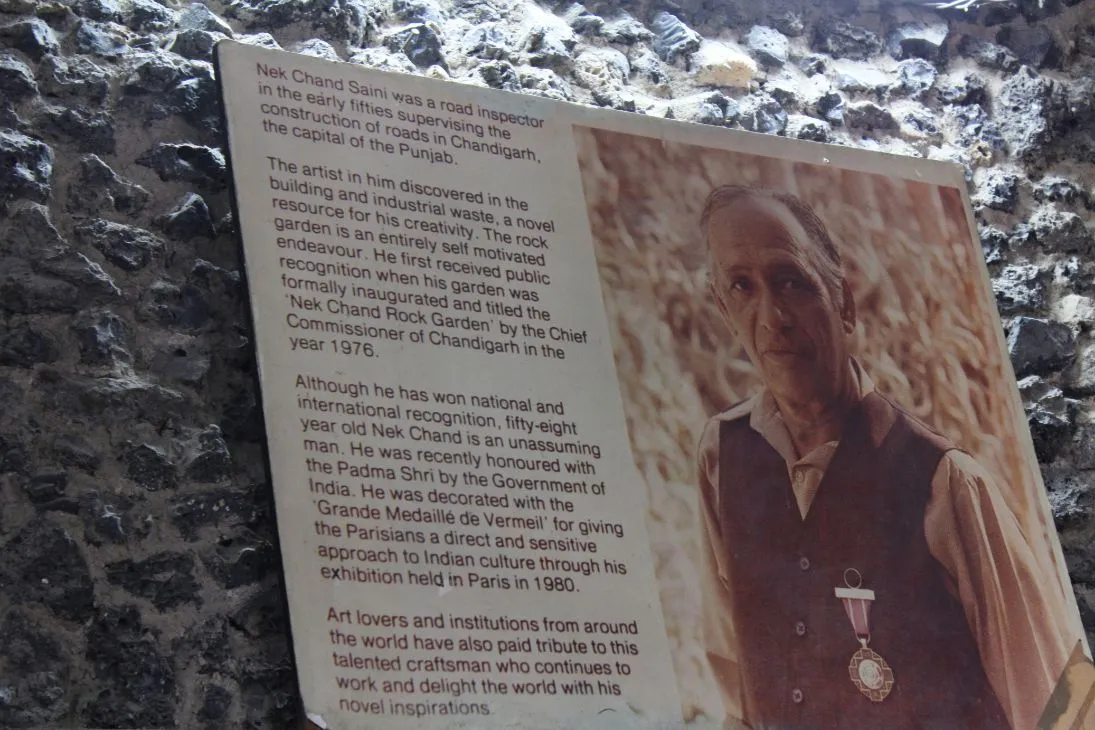

This is an excerpt from the chapter ‘Anthropocene: “Modern” Chandigarh, Nek Chand, Rock Garden and Dalitbahujan Anthropocenes’ in Mukul Sharma’s Dalit Ecologies: Caste and Environment Justice (2024). For our interview with Mukul about how he came to write this book, click here.

In his entire lifetime, Nek Chand lived with scars and experiences of displacement. His creation of the Rock Garden was a creative way to deal with the destruction and displacement all around him.1 His childhood accounts, few and far, narrated his village life with family, land, agriculture, and animals, and how Partition destroyed it completely. In a climate of violence and disorder, Nek Chand set out from his native village with his parents, four brothers, and two sisters. For twenty-four days of their footloose journeys, they encountered many dangers and crossed the river Ravi:

After trudging over sixty miles [100 kilometres], he finally reached the north of India and settled in the town of Gurdaspur with his family. In 1949, however, he left them to make his way to Karnal, where he joined the staff of the highway department. In the following years, Nek Chand was to live temporarily in Panipat and Faridabad.2

Both his parents died just after their exodus to India: ‘Partition devoured them. Had there been no Partition I am sure they would have lived for many more years.’3

Early one morning in February 1973, an anti-malaria party came upon a stocky middle-aged man in his underwear arranging rocks and stones in the rubbish dump that was. And word flashed along bureaucratic channels up as high as the District Commissioner. Nek Chand wasn’t sure whether he’d be congratulated or arrested – for destruction of Government (waste) materials (and unauthorised use of Government land). He wondered – he said – whether a bulldozer would rumble down and flatten everything.4

In the 1990s, the government decided to build a road right through the middle of the garden, for the exclusive use of VIPs. Thereafter, trees were cleared and bulldozers arrived at the garden wall to demolish certain structures.

The early experiences of displacement were overwhelming and earth-shaking in a post-colonial country, which resolved to their ‘people’ to ensure social, economic, and political justice. Chandigarh was one of the first places in India where multiple displacements unfolded: complete destruction of several villages, their land, and livelihood activities; duple displacement of Partition ‘refugees’ from their new settlements; villagers working as construction labourers in the developing city and living in labour colonies; use of the Land Acquisition Act of 1894, ‘cheap’ value of land and natural resources and denial of just compensation to the villagers; and state repression and people’s resistance. The unquiet around displacement and dispossession simmered for decades and continued to haunt the city. The ‘periphery’ of the city was formally converted into ‘a controlled area’ to serve the ‘centre’. The rural enclosure was to fulfil the daily needs of the Capitol. Le Corbusier wrote a letter to the Punjab Chief Engineer:

My idea is that the farming must be conserved directly near (in contact) with the Capitol Area, so that the life expressed by the work of the peasant will be seen and appreciated: the order of the fields of sugarcane, wheat, etc. And little by little the way of modernisation of the peasant life will appear.5

There was thus a fetishizing of rural India’s ‘primitiveness’, and furthering a paternalistic agenda of using modernism to civilize the non-Western world – ‘an idealized image of rural life to provide sharp, side-by-side contrast with the progressive modernism of the Capitol Complex’.6

Living amidst such cycles of displacement, Nek Chand moved around the displaced villages and collected materials from destroyed households, employing ‘squatter’ techniques. Several of these are prominently displayed in the garden, an integral part of its sculpturing: broken pottery and ceramics, fragments of glass bangles, human hair, tube lights, and bicycle parts. According to a research study, this showed Nek Chand’s desire to highlight and prominently display ‘pre-Chandigarh village life’.7 There were miniature villages created in the garden, with or without the materials from the displaced villages, but they had the reminisces of lost and crushed people. It was aptly observed:

Chand has crafted a material record of the city’s acts of construction and displacement. As a result, the Rock Garden is arguably the only place in the city that visually records the original settlements together with the developing and developed city, and that signals, however indirectly, the history of movement, construction, and both upwardly mobile and displaced lives.8

An important material fallout of the construction of Chandigarh was the generation of waste in construction, market, infrastructure, energy use, consumption, and disposability. In the 1950s, the Chandigarh building project was fast developing in ways by which agricultural soil, forest lands, and human habitats were turning into concrete masses of waste. Waste, like the displaced labourers, was a ‘matter out of place’,9 signalling ruins of everyday lives, and traces left behind by the new-age machines. During this same period, Nek Chand, belonging to the Mali caste, often considered a part of wasted lives and refuses of society, became a collector and narrator of waste. Waste was not his ‘birth-based polluted occupation’, but it provided him ground material to sculpt stories of the past, present, and future of the earth. The collection of waste was not stigmatized hazardous work for him; it was a creative, challenging endeavour to constitute innumerable faces and facets of human-non-human worlds. Since the beginning of 1958, Nek Chand travelled to several sources of waste – individual, social, public, economic, and industrial – to comprehend their production cycles, and used them to build a new physical world. His son Anuj Saini stated in an interview with me:

Nek Chand’s caste was considered lowly and backward within the larger social circle, but he never allowed caste discrimination and subjugation to come in his way. He was dealing with wastes and discards not as a polluted and dirty person, but as an illuminated and creative person, who was trying to carve a world from below. In our childhood, he filled us with a sense of humanity and dignity, akin to being equal to everybody in terms of education, skills and opportunities, even in a caste-based place.10

Saini Samaj, an organisation of people belonging to the Saini caste, considered a ‘backward’ caste in Punjab, facilitated Nek Chand in his lifetime.11 Nek Chand kept in regular touch with the Samaj and participated in its social and cultural activities, However, ‘Nek Chand was not limited to the Samaj. He had a complex and sensitive relationship with caste in community activities’,12 explained Harbhajan Singh Saini, vice president of the Saini Sewa Samaj in Punjab.

The Rock Garden was primarily constructed by waste materials of the city. Unlimited and unwanted, these discarded materials captured the eyes of Nek Chand, who started collecting and storing them regularly in a secluded forest area and began their casting and placing in the night hours. It is virtually impossible to make a list of his collections: broken crockery and sanitaryware, white pebbles, fused fluorescent tubes, huge limestone boulders, precast concrete, brick and cement tiles, sheet metal, woods, street light poles, red sandstone flints, tar drums, brick bats, terrazzo tiles, reeds, thatch, bamboo, rubble, coal slag, lime-kiln waste, cement, electric fitments, mud-and-hay plaster, foundry and engineering materials, broken electric plugs, blown-out light bulbs, steel slurry, iron alloys, different metals, machine and automobile parts, frames, mud-guards, forks, handlebars of bicycle, tree trunks and branches, steel bars, Coca-Cola bottle-tops, porcelain, damaged pots, scraps of cloths, wasted furniture and furnishings, chemical jars and containers, and tons of rubbles.13 There are ample accounts of how Nek Chand collected the waste materials of the city. As a road inspector, he was well-versed with the new geography and economy of the city. He could thus correctly locate from where to collect what and how to hide them completely. He, on his old bicycle, roamed around construction and debris sites, and transported waste on its carrier. He went to displaced villagers, construction workers, and industrial localities, and asked people for their garbage. At his hidden place, he created a small, makeshift hut structure, like a temporary home of a displaced villager, and blocked its view from outside by arranging bitumen drums. He fired the bicycle tyres or abandoned cars to make lights in night at his workplace.

He used cement bags to cover his head, to protect himself from swarms of mosquitoes. ‘No storm, thunder, rain, or even the fear of wild animals could deter him’,14 recalled his son Anuj Saini, an artist and member of the Rock Garden Society. Later, he also developed centres at industrial, commercial, and colony areas to collect waste, and used small trucks to transport heavy materials.15

For Nek Chand, waste of the city was his key focus, and he concentrated his energy on the reconfiguration of wasted things. Simultaneously, as a collector, he was also gathering objects – rocks and stones – which held memories of lives and times gone by. On his bicycle, he travelled through the Shivalik hills, the seasonal Sukhna Cho, Patiala Rao and Ghaggar rivers, and gathered countless natural rocks and stones, feeling that ‘they have a soul’, and ‘in every stone there is a human being’.16 In their remarkable study, Bandyopadhyay and Jackson characterized Nek Chand’s rock collection as a ‘passion bordering the chaos of memories’, and marked its various details and distinctions:

Rocks were selected depending on their appearance, texture, erosion, difference from previously selected rocks and whether they resembled something else, i.e., a face, person or an animal…. In the early collection one can discern two categories of rocks: first, the rocks found on the riverbed – mostly basalt – eroded and shaped by its environment into intricate forms, clearly suggestive of humanoid or bestial formal qualities. Secondly, the heavier, smoother, more rounded and less eroded monoliths, often with deep penetrative incisions or apertures, suggestive of primitive amorphous life form, and thirdly, a small number of magma-like rocks evidently shaped by volcanic activity.17

I regarded myself as neither an artist nor a craftsman. I myself was completely insignificant. I had no idea about anything, except for the fact that I was devoting my time to a task I was passionate about. I worked to the limits of my strength…. It all came from my heart and my imagination. My intention was to build a kingdom for gods and goddesses. It is a gift from God. This garden is more than an offering to God.18

- Bandyopadhyay and Jackson, The Collection, the Ruin and the Theatre.

- Lucienne Peiry and Philippe Lespinasse, Nek Chand’s Outsider Art: The Rock Garden of Chandigarh (Paris: Flammarion, 2005), 12.

- John Moizels, ‘Nek Chand: Creator of a Magical World’, in Vernacular Visionaries, International Outsider Art, ed. Annie Carlano (New Haven: Yale University Press 2003), 67.

- John Moizels, ‘Nek Chand’, 32.

- Le Corbusier, ‘Chand Indes Urb Plan’, General No. 11/30887 (Paris: Foundation Le Corbusier, 1953).

- Chalana, ‘Chandigarh’, 68.

- Iain Jackson, ‘Politicised Territory: Nek Chand’s Rock Garden in Chandigarh’, GBER 2, no. 2 (2002): 51–68.

- Bonfitto, ‘The Rock Garden’, 130.

- Douglas, Purity and Danger.

- Interview with Anuj Saini, son of Nek Chand, Chandigarh, 12–14 August 2021.

- The Saini Samaj has hailed Nek Chand as one of their celebrated heroes. See http://www.sainionline.com/personalities/nek-chand-saini-creator-of-rock-garden, accessed on 1 September 2021.

- Interview with Harbhajan Singh Saini, Chandigarh, 8 July 2021.

- S. S. Bhatti, Rock Garden in Chandigarh: A Critical Evaluation of the Work of Nek Chand (Chandigarh: White Falcon Publishing, 2018).

- Interview with Anuj Saini, Chandigarh, 12–14 August 2021.

- Bhatti, Rock Garden in Chandigarh; Peiry and Lespinasse, Nek Chand’s Outsider Art.

- Bhatti, Rock Garden in Chandigarh, 218.

- Bandyopadhyay and Jackson, The Collection, the Ruin and the Theatre, 24–27.

- Quoted in Peiry and Lespinasse, Nek Chand’s Outsider Art, 15.

-

Mukul Sharma is a professor of environmental studies at Ashoka University, India. He has published Caste and Nature: Dalits and Indian Environmental Politics (2017), Defining Dignity: An Anthology of Dreams, Hopes and Struggles (ed., 2005), and Unquiet World: Dalit Voices and Visions (ed., 2004). He has worked in media and civil society organisations and was associated with World Social Forum, World Dignity Forum, and National Confederation of Dalit Organisations.