With inputs by Aarya Pathak

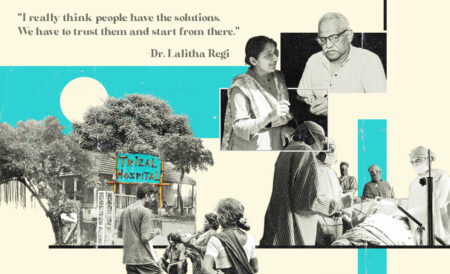

As India grappled with a deadly second wave of Covid-19, it laid bare years of underfunded and neglected public health infrastructure that left millions of citizens breathless and abandoned. With hospital administrators taking to Twitter to provide live updates about diminishing oxygen supply, multiple patients dying overnight in hospitals owing to low pressure of oxygen, oxygen langars in parking lots run entirely by nonprofits that run wholly on citizen donations, midnight court hearings and animal crematoriums turned into human crematoriums, the country was lit up by the eerie afterglow of an unprecedented number of mass funerals.

Death may not be the equaliser it promised to be but the second wave did bring it close. This time, no private assets or property could save the rich. In April, this cruellest month, no ‘contacts’ in high places could ensure you a bed and no phone call could get you a ventilator, as government officials, judges, diplomats, and their families, struggled to get hold of resources. It was each person to their own, navigating a dystopian nightmare. Except that they were not alone.

Overnight, nameless strangers on the Internet became first responders to 24×7 SOS calls, part of a spontaneous eruption of citizen action, in the wake of government inaction. Most of these volunteers were young students, working professionals and members of parents’ groups who rose up to replace a failed state. Social media, where we go and find its much-maligned superficial solace, was suddenly flooded with too much reality — requests for beds and oxygen and plasma and Remdesivir.

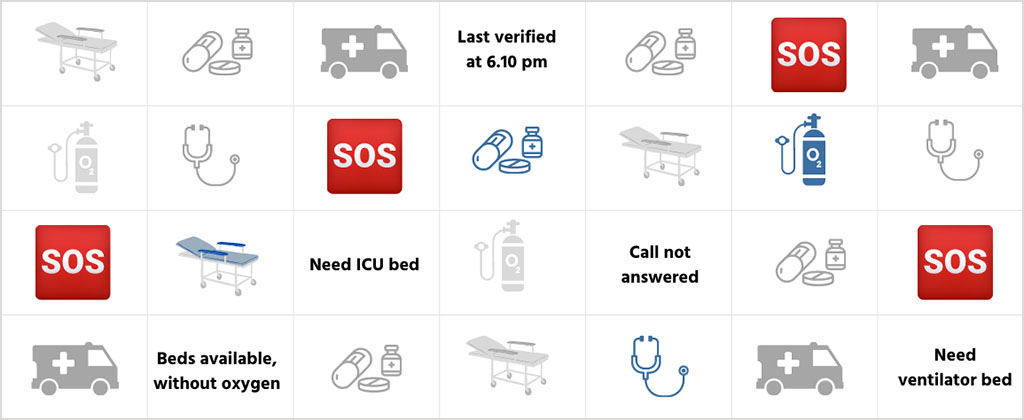

When the second wave hit, and we started volunteering, we first thought, how difficult could it be? Social media was filled with nicely designed dashboards and helpline numbers; we felt like every resource was just a call away. The digital repository was so rich that we felt that the ground conditions were getting strengthened each time we clicked.

In the second week of May, Aarya was searching for an oxygen cylinder and ICU bed for someone in Delhi. She stayed online listening to phones ringing continuously, phones that no one answered. 8 pm, 11 pm, 2.30 am. At 3 am, finally, someone picked up the call and said, here are eight numbers, try these. She already had a list of nearly 40-45 numbers. She was in her hometown, Pune, and unfamiliar with Delhi’s topography. Every time someone—a patient or an attendant—told her their location, she had to go back to Google Maps to check the proximity. This was her sixth day of volunteering from her room in Pune. Because of the lack of a centralised number/database, all the leads float like a branch in the sea that is Twitter, in the ocean that is Instagram. On a good night, that branch leads to land. That night there were no branches. At 7 am she called my friend to say, “I didn’t find any.”

The capital city of Delhi has 1.05 beds per 1000 population, whereas WHO recommends 5 beds per 1000 population. In an interview to NDTV, Dr. Madhu Handa, Medical Director, Moolchand Hospital, said, “We request our patients to use their single room as a double room and now there are no single rooms available.” But after those hundreds of calls, I knew it was worse. Holy Family has changed its 40 bed ICU to a 60 bed ICU, and every inch of its corridor was used.

At some point this realisation comes to every volunteer. It is not that I couldn’t find any beds. It’s not that I wasn’t working hard enough or smart enough. As Suman said to us, “I cannot add new beds on ground; all I am doing is juggling with information about available beds.”

Data

One of the biggest challenges that came about during volunteering was sorting through the massive amount of data available on the Internet. Multiple Excel sheets. Multiple Google sheets. Sheets for oxygen, beds, medicines across multiple cities. Duplication of data caused a lot of problems. Suppliers began to ignore or switch off their phones because of the multiple verifications calls they received in a day [they moved to WhatsApp messages instead; much higher success rate]. With the scarcity of oxygen resources and beds, leads would get exhausted within minutes of being put out and Excel sheets became outdated every hour. Hence, volunteers would need to verify each and every lead every hour. Also, this notion of ‘verification’ was not as simple as it sounds. There was no way for volunteers to know just via a phone call if the oxygen supplier or a medicine seller was trustworthy or not. Multiple scams were reported from ‘verified’ lists on the Internet. Increasingly, volunteers started blaming themselves if their verified data led to a scamster.

Deepshi, a second-year history student at Delhi University, has been volunteering in her individual capacity and also coordinates relief work with the All India Students Association (AISA) as their member. “We have a lot of AISA WhatsApp groups which we use throughout the year to mobilise and volunteer for different issues, and those groups quite organically turned into a makeshift public health network in this wave. I shudder to think how many more lives we would have lost, if we did not have these pre-existing online communities,” she says.

“It was a nightmare to begin with. I hadn’t thought things would be so bad. We had planned to organise and collect city-wise resources; but what could we collect when there was no information and resources kept depleting by the minute? Half the numbers didn’t work, and even the ones that did, led to dead ends because of acute shortage.”

Verifying data also entailed keeping track of how rules were changing in hospitals and pharmacies, keeping track of government-approved suppliers and pharmacies, trying to differentiate between fake and real medicine dealers, trying to identify trustworthy oxygen concentrator suppliers across the state, etc.

Bearing Witness

In Maharashtra, Sachin Sherkhane, part of Amhi Covid Yoddhe, says, “We were all searching for a ventilator bed one day. After three hours, we get a call from the patient’s family to inform us that the patient was no longer alive. From that incident on, there was always fear. I cannot bear to think of the shortages we are facing when my phone rings. I always pray that the person on the other side should not be asking for something which I really cannot arrange at this moment.”

As we saw the public health system collapse, we witnessed 16-year-olds and 20-year-olds, with little experience of handling a medical emergency and sans any formal training, help families of critical patients. Geetanjili, a final-year student at Delhi University who is also a volunteer with a Delhi Medical Support Group, shares how she was sceptical, and frankly quite scared to take on cases of critical patients. “I had been part of this group since the 2020 pogrom in North-East Delhi where we had provided medical assistance and help to riot victims. The group slowly transitioned into a Covid relief group this year, and the scenario had drastically changed. It is only when the doctors in the group held a short induction for us that I felt confident enough to volunteer as a case worker for critical patients who needed beds or oxygen.”

Often volunteers found themselves stuck in situations where they didn’t know if a patient could be given assistance with an oxygen can instead of a cylinder. “It is only when we had a meeting with doctors that we got to know in which situations one could use a concentrator, cylinder and can, and whether they were substitutes of each other or not.” Saanchi, (who also has a day job at a startup) is the founder of TYCIA Foundation, which has been doing considerable amount of on-ground Covid relief work. Geetanjili says, “When I was volunteering as a medical support volunteer during the Delhi riots, I went through a harrowing experience transporting a critical patient to a hospital in an ambulance, and had decided to never take on such kind of volunteer work ever again. However, when the second wave happened, I just couldn’t have not done anything. Once you sign up, you just go with the flow.”

Most volunteers trained themselves on the go. They experienced community and peer learning, and adapted to evolving situations with little time to pause and prepare for. Unlike doctors, medical professionals and nurses who are specifically trained to keep a critical, objective distance from any patient’s case, volunteers had no experience or training in maintaining objectivity, which had severe consequences on a psychological level.

Across the spectrum, volunteers told us that despair and grief had begun to feel like a luxury. Where every minute determines someone’s chance to access oxygen, how could any volunteer take a break without feeling guilty? The only time I curled up and cried was when an 18-month-old baby died because I couldn’t find an ICU bed on time.

An emotionally overwrought Shobha, a social worker in Rajasthan who volunteers on the ground with Praveen Lata Sansthan in Jaipur, narrated her helplessness when she lost her own family members a few weeks ago. “Both my mausi and her son passed away due to Covid. I was unable to arrange oxygen for them and shift them to a Jaipur hospital on time. Looking at them gasping for breath, I felt extremely helpless and kept on thinking, what is the point of my work as a volunteer if I could not save my own family members?” She says she cannot get her cousin’s face out of her mind. He was barely 20. But she adds, “It has been six days and I still have not reconciled myself with his death, which is what perhaps keeps me going. I keep on thinking – agar aaj bhi main ghar baith gayi, toh kitne log mere bhai ki tarah apni jaanein kho denge, jinko hum se madad mil sakti thi?”

Similarly, Rukmini, a student volunteer from Ambedkar University, Delhi, talks of the absurd conundrum volunteers are forced into while experiencing loss and death. “We are constantly oscillating between two poles—one, which compels us to see every death as a statistic so that we can keep going on, mechanically, and help the ones who have not yet succumbed, while the second pole forces us to pause and acknowledge the human cost of this virus, and slowly absorb all the losses around us, get to know the patients that died so that they are not just another number.”

As we grapple with one tragedy after another, we have collectively learned to cope by numbing our emotions, repressing our stress and postponing our mourning. As students, at a time when we should have been worried about assignments or college farewells, or jobs, we see 16-year-olds calling up cremation grounds in the middle of the night trying to find a place to bury their dead. All fear has left our bodies over the course of the second wave and we have completely shut off our emotional response system. The fear that now remains is the impending unpacking, facing and reconciling with what we have witnessed, years later.

Divided

While SOS calls and requests for beds may have seemingly declined on social media in the past week, it is imperative to note how only metropolitan cities have access to social media. The digital divide does not allow rural realities of the pandemic to be displayed on Twitter or Instagram. Information is scarce and information dissemination on the part of local governments about the pandemic has not been very efficient. “My aunt who lived in a village in UP never woke up in the morning. It was only after her death that we got to know she was Covid positive. Everyone thought she just had a small fever,” says Geetanjili.

Geet, who volunteers with the Sangwari Gond Network, a few kilometres away from Bhopal, reminds us that rural volunteer work carries on exactly as it has been for decades. On foot. “We have been providing rations, medicines and multivitamins to bastis and members of our Gond Samudaaye during the lockdown. We also try to volunteer and give rations to the Denotified Tribes (DNT) as the government has not been doing much for them,” she says, acknowledging the spread of the virus.

“I have my own fears when I go out to volunteer and distribute rations. We have to be patient and constantly tell people to maintain social distancing rules while they collect their supplies. I also have a family to go back to, and constantly [worry] about giving them Covid. Meri maa dar rahi hai ki kai main itni door jaati hoon volunteer karne lekin dil nahin manta ki hum ruk jaaye.”

Geet also flags the mixed signals by the state, vis-à-vis information dissemination, in light of mass election rallies and Kumbh Mela gatherings. “What distressed me the most was seeing the behaviour of policemen towards the mazdoors in our area. They would often beat them up at the chauraha for ‘flouting’ lockdown rules. If the government is not responsible enough to make the public aware about the seriousness of the pandemic, how is it the mazdoors’ fault that they are out on roads trying to make a living for themselves?”

Shobha from Praveen Lata Sansthan in Jaipur reminds us that while the urban centres cry for high-flow oxygen concentrators, in rural India, the hunger pandemic rages on.

“I have often been rebuked by my family for stepping out as a volunteer, especially as a woman. But I don't think I can stop. I have visited houses of people who were literally on their knees crying, showing me their empty jars and utensils. Ek aurat toh mujhe alag se kitchen mein lekar gayi aur boli ki mujhe sharam aa rahi hai aapko bataate hue lekin aaj humaare paas dal chaunkne ko tel bhee nahi hai, hum ubli hui dal kha rahe hain. I immediately called up someone and tried to arrange rations for these families. How can I abandon my own people in these distressing times when our villages don't have enough medical resources and people are facing economic hardships?”

Rashid Ansari of Mazdoor Kitchen in NCR concurs. “The need for food is just extreme. There are people dying but then people who are alive need food also. My experience with the administration was horrible. Six months ago, we were desperate because ration was just lying in godowns and no one saw that it gets distributed.

This is not about charity or philanthropy, it’s about right to life.”

As a generation of children and young people who have lost so much—from parents to friends to a classroom education to opportunities to picnics to dreams to homes to spaces and times—we shudder to think of the day we will slowly pick up the pieces of these broken dreams and lost chances and grieve as a generation, at our loss of could-have-been. This time, we can’t take to the streets. And thus, another night passes where dissent translates into ‘voluntary citizen action’ and all we can do is verify another number on yet another Excel sheet. For the nth time.

“What I don’t understand is,” says Deepshi, the history student, “how can people glorify themselves for doing this kind of volunteer work? We are being forced to do this; it should not have been our responsibility or duty in the first place.” The kind of glorification of the volunteer action that we have seen in the mainstream media, in the absence of a political analysis, deliberately puts the conversation about structural reform in the public health sectory on the back burner.

As CoWIN glitches invite a new army of volunteers to help 68 percent of India get a vaccine slot, there is compendium of rage on social media. The writers of this piece recognise that anger is useful to sustain such moments and builds solidarity too, but it is the radical power of vulnerability and compassion that will get us through this.

How To Mobilise Digital For Rural

Keeping in mind that this is happening on a digital scale, how can we reach people who don’t have access to social media? If you are an organisation that works with grassroots workers, you can:

- Facilitate digital training of rural field workers with a special emphasis on using social media for amplification. Harness open source tools and aggregator apps to make sure SOS messages get heard. The Third Eye has a repository of digital trainers and can put you in touch for a two-day training.

- Connect rural networks to urban networks across cities. Existing volunteer networks to be encouraged to amplify rural SOS calls and ground realities so they can tag relevant state and district authorities.

- Build verification protocols and a discipline of maintaining a live database of oxygen cylinders, telemedicine doctors and people with Covid19 symptoms in your mohalla.

- Encourage active anti-misinformation campaigns on social media and WhatsApp groups, especially regarding vaccination.

- Make use of jhola doctors to fight misinformation around Covid-19, and also build appropriate awareness and behaviours, especially with regard to social distancing and isolation and what that means for rural households.

- Build two teams: on-ground and online, and encourage a live, seamless coordination between the two. On-ground teams, following Covid protocols, provide live information to the online team that can reach district hospitals, telemedicine doctors, oxygen suppliers and ambulance services as the case requires.

Register at Rural Response Tracker to find a consolidated list of rural resources and also to volunteer to verify rural leads.

Follow Khabar Lahariya’s consolidated Covid19 resources and helplines here.

Aarya Pathak is an Urban Fellow at IIHS, Bangalore. She likes to research around gender, housing, public health and their intersection with media. She can be reached at [email protected].