The Third Eye continues the landmark conversation between Pooja Pande and Suneeta Prajapati of Khabar Lahariya, on what it means to be a rural journalist, to be online as a rural journalist, the difference (or not) between trolls and fans, how the mobile offers the woman the twin axis of desire and violence, and the remarkable negotiations that emerge for young working women as the online world starts mirroring the real one.

First published by Point of View and the Internet Democracy Project in Imagine a Feminist Internet in 2019.

Suneeta in her show Jasoos Ya Journalist.

In her Image: Walking the Tightrope, Navigating the Online & Offline

“See, even as child, I’ve just always gotten along better with boys than girls.”

PP: Are the men you’re friends with mostly media peers?

SP: Yes, most of them. Some are still studying, some are in Delhi, and one or two are private teachers. But yes, mostly all media.

PP: Suneeta the Patrakar is also Suneeta the 22-year-old. Is also Suneeta the 22-year-old woman. Is also Suneeta the 22-year-old woman living in Mahoba, Uttar Pradesh. How do you bring all of them together into your digital identity?

SP: Okay, so there was this time I put up a picture and this banda I know somewhat, not too well, commented ‘I Love You’. I met him on my way somewhere and I pulled him up for it – that he should be aware of the consequences of just typing something, that it’s going out into the world, and how I can decide to take some action against it, etc. He apologized, of course, and made excuses – how someone else had logged into his account and did that. Anyway, I deleted it, because you can delete it apne aap se, so that’s good – but I made it a point of clarifying to him, even if it meant accosting him.

I manage my own account and in my family, nobody’s checking up on me like that. But the usual family response to this will be that you’ve only asked for trouble, tumhari hi galti hai.

Anyway, I’m clear about myself – local mein I am responsible for my reputation, and my image. Mujhe apni chhavi par dhyan dena hai, use banakar rakhna hai (I have to be mindful of my image). Because I am here to work, I want to move up in life, go forward. So, I can’t get into all this.

Let me tell you about another time when there was a community wedding event in Kabrai, which I went to cover. I went with a fellow media peer, and I met another one there, who said, ‘let’s get married’. I said ‘Okay, let’s, what’s the big deal?’ I mean, we’re just having fun. Another friend warned another of my friends at this ‘Suneeta se bachkar rehna. Phaswayegi. (Beware of Suneeta. She might get you into trouble)’. So then, that other friend…

I think that’s when I thought that only I am responsible for my image, and mujhe woh dekhna chahiye theek se, I need to be more careful. Even when I’m only kidding. I want to go very far in life, and if all this comes back to haunt me, nip my prospects, I’ll never forgive myself. So, I need to focus on that, getting into all this is not important and not good for me. It’s a rural area, it’s a small town, there are assumptions and presumptions around women and I need to be mindful of them, especially as I am not following a conventional life path at all.

PP: This image you speak of, what should it be?

SP: Primarily, that she’s a good reporter. She’s very smart with her work. I should be known for that.

And then also that this is who she is, yeh mera swabhav hai, hasne-bolne ka, sabse baat karne ka, purush ho ya mahila (It’s in my nature to crack jokes, speak to everyone, irrespective of gender). I don’t want anyone to think that she only speaks with this one person, because that’s not who I am. I am someone who likes to talk to everyone, who likes to get to know everyone to some extent, and most importantly, is very keen to learn from everyone. This is who I am, and I want people to know this about me. That this is Suneeta – it’s what makes Suneeta Suneeta.

PP: I understand this unapologetic way of being – to be recognised and cherished for who you are, deviance be damned! I can empathise. But it’s tougher for women, isn’t it?

SP: Of course it is. For men to understand that just because I share a few laughs with you, it doesn’t now suddenly give you the right to now talk about my lips and eyes? To me it’s clear, no? I don’t understand how one leads to the other.

On WhatsApp, if I would put my DP, people would download it and send it back to me, with the comment ‘Nice photo’. Or those obviously physical ones, commenting on my looks, my eyes, my lips. I’ve stopped posting DPs for this reason, I already know how I look, how attractive I am, but I really don’t want to hear it from you.

Tumhari zubaan se nahi sunna mujhe, it becomes crass.

PP: So if I played the devil’s advocate, I would say that if photos are for public viewing, then what is wrong with someone admiring them? How and where do you draw the line between a compliment, or genuine admiration for you and your work, and what you’re recognising as violence, or a violation?

SP: It’s a multi-pronged thing, isn’t it? Like I’ve just launched my show, right? I sent it to several people and lots responded very positively. ‘Bahut achcha hai, badhiya laga, aapka bolne ka tareeka bahut badhiya hai, editing bahut achchi hai, story badhiya sunaai (Great show, you have a good way of speaking, good editing)’. And then there were those seemingly positive comments that only compliment me on superficial things – those were along the lines of ‘Aapke kapde bahut achche hain’, ‘Aapke kaan bahut sundar hai’, ‘Aapke honthon ki lipstick achchi lag rahi hai’. So, comments like those, you can understand what the perspective is. It’s not like they’re engaging with what I’m saying, the content of my show, right?

PP: What if women said these things about your show? Your shade of lipstick, etc.

SP: You know, women have a certain lightness about them. Especially, rural women – they’ve got this totally non-serious attitude about things, or a light attitude, shall we say. They like to rib you, joke about, hasi mazaak karne ki aadat – it’s a way of getting to know you also. If you get all high and mighty about comments around lipstick, then they’ll brand you mean and arrogant. Also, women can never be a cause of violence. She might want to use the lipstick shade at the most. She might want to buy my sweater. Those could be reasons she’s commenting. With men, it’s all comment baazi, mahila hai toh maze lo, bas.

PP: What about the men who are engaging with the content? Who comment on the editing, or the story?

SP: It’s feedback for me then, no? Some of the men are known to me – they’re my mohalla wale, or my college folks – I share my work with them on a regular basis. Some of the men are my peers in the media. Some are followers of my work, and KL’s channel. Some are like, friends of friends.

PP: And those who mention lipsticks?

SP: You know, it’s often the men I engage with personally/professionally in a more open way who make these kinds of comments. Jaise zara khul ke baat kar li, thoda mazak kar liya (You open up a little bit with them), those men often make those kinds of comments.

PP: But staying safe and speaking up can go hand in hand, you feel?

SP: Yes, in some sense. Because staying safe is different from staying quiet, or suppressing your voice. Dab ke nahi raho (never repress yourself), and never tolerate any nonsense, anything being done to you. … Somewhere down the line, and in fact, over the last year only, I figured out FB settings and how I can choose who can see my pictures, or find me, and all that – I changed them to my preference.

This Internet is a great thing, but there’s a lot of hidden evil on it. Most don’t know it. I didn’t know it. And then we fear what we don’t know. So, it’s best to know. That’s also a way of staying safe.

PP: What is the balance that needs to be achieved? What is the worst-case scenario in your head?

SP: So, let’s pretend a photo of mine turns up in an unpalatable context. It’s possible, right? That can become a huge problem for me. And why so? Not because of what false rumours will start circulating about me and my “bad” character, which, undoubtedly, will happen. That’s all faaltu charcha (mindless chatter), and I don’t care for it. What will become a problem for me, personally, is that my freedoms might come into question. Right now, my parents and I have negotiated these freedoms in my life. I come and go as I please, I follow a line of work that’s unconventional, I travel so much. If something like a photo can take away these hard-earned freedoms, and it totally can, then that ruins my life and me, doesn’t it? My parents have zero understanding of the Internet and how it works. They will not even be able to understand what it’s about; they will assume that I have done something wrong, that I have hidden something from them. They have no concept of what can travel where, how and why, and how fast, all through the click of a button on a phone. They only understand that I do some reporting work, I go to jan sabhas, I go to thanas, etc. They can never fathom, in this lifetime at least, that the Internet is another world. They have no inkling of it.

If that were to happen, I know for a fact that whatever I say to them, will not go down well. Unhe dhakka lagega, and they will only react. Their dreams will shatter; it will be the end of the world for them. And they will see no option but to impose restrictions on me.

PP: How is it different for the boys?

SP: My brothers made their FB accounts and were using WhatsApp without anyone knowing about it. It’s a non-issue. But, I remember when my accounts were made and I was using social media, my brothers would check my phone to see what I was up to. I would get very angry, I would refuse… I would delete things before the phone came to them, knowing that they would object to some things. But it was okay for them to be that way, because they’re boys.

I have younger brothers and I have made it my secret mission to make them aware of this online world and how they need to be mindful of it. See, boys never think even once about all these things on their own. I mean, they don’t need to.

I admonish them about what they’re doing online, how they’re spending their time online. They’re on my FB, so I get to know what they’re up to and I keep tabs on them. Like, if they share some weird photos. Or become part of groups that are up to no good. Like there are FB pages that are for time-pass of local boys – Haso Hasao, Ladki Patao – that are basically crap and a waste of time. They’ll put up some girls’ pics there and say share, like, number de do and all. Lot of people get involved, because that’s how you get publicity online. When I saw my brothers on it, I told them to exit such pages, yeh cheezein achchi nahi hoti hai. I tell them about how FB monitors how you use FB, aapka data collect karta hai, and how they need to be aware of all this, mindful of this.

PP: Basically, you scare them?

SP: It’s good to be scared a little bit! They’re young and who else will teach them these things? Staying safe is important for them also, after all.

Engage the Troll: Honest Questions, Honest Answers

“Even broken clocks show the correct time twice a day, right? That’s how I see those you call trolls.”

PP: How do you separate the anger from the acknowledgement? Seeing how a negative comment or abuse is also an opportunity…

SP: The way I see it, the first time, I can let it go with a very mild admonishment. Like, going back to the lipstick, I will say something like ‘Aapke ghar mein koi nahi lagata lipstick, jo aapko meri hi dikh rahi hai?’ So, it’s a mild response I would say, but the intent is clear – watch out, I have not liked it. Most will not do it again. If someone still does, then I can raise the level of my annoyance or anger and like I have done, take it offline also. Mostly, a lot of support comes my way in the first time I show offence, so it doesn’t go much beyond it.

I reply to all the comments, I make it a point. If I only comment to only one, and like another, then the one I didn’t respond to might not like it. So, I write back to each and every one. I think that’s important, jude rehna. I remember reading somewhere once agar kisiko izzat doge, toh vaapas izzat milegi. It really stayed with me. And I do feel a strong sense of community. Today, people know me, they engage with me, I have built an audience, toh inhe saath lekar chalna hai, na?

This is true for work and life. It’s like when we set off somewhere, we might have to stop and ask a few people for directions, we might have to ask someone else for water, and we might have to deal with some unruly types too. It’s all part of the journey.

Whether it’s good or bad, you need to stay connected. You can give the benefit of the doubt the first time there is some bad response – like trolling – but not after that. But there’s no need to shut it out.

Kya pata usse kuch kaam hi pad jaaye, hai na? So, it’s better to stay connected in some sense – Hello, hi tak rehna. If I meet a guy who’s trolled me on the road, and can give me a lift to the station, and I’m not getting any means of conveyance, I might as well take a ride with him. If I’ve blocked him everywhere on my social media, then I can’t ask him offline either.

But if I’ve maintained a hello-hi relationship, then I can, right?

I’m a very strange creature for these parts – a woman reporter. On top of that, I also want my friendly nature to be part of my identity, without any unnecessary conclusions read into, or drawn from it. I know that this is a fight I have to fight every day.

It’s Not About the Tool, It’s About Who Wields It

PP: So, is the Internet as powerful as it is problematic?

SP: Yes. But is more powerful.

PP: Tell me why you say that.

SP: I find this space of social media and being online is a space where things can happen, where you can make things happen. Sure, there is the good and the bad, but it is all about action.

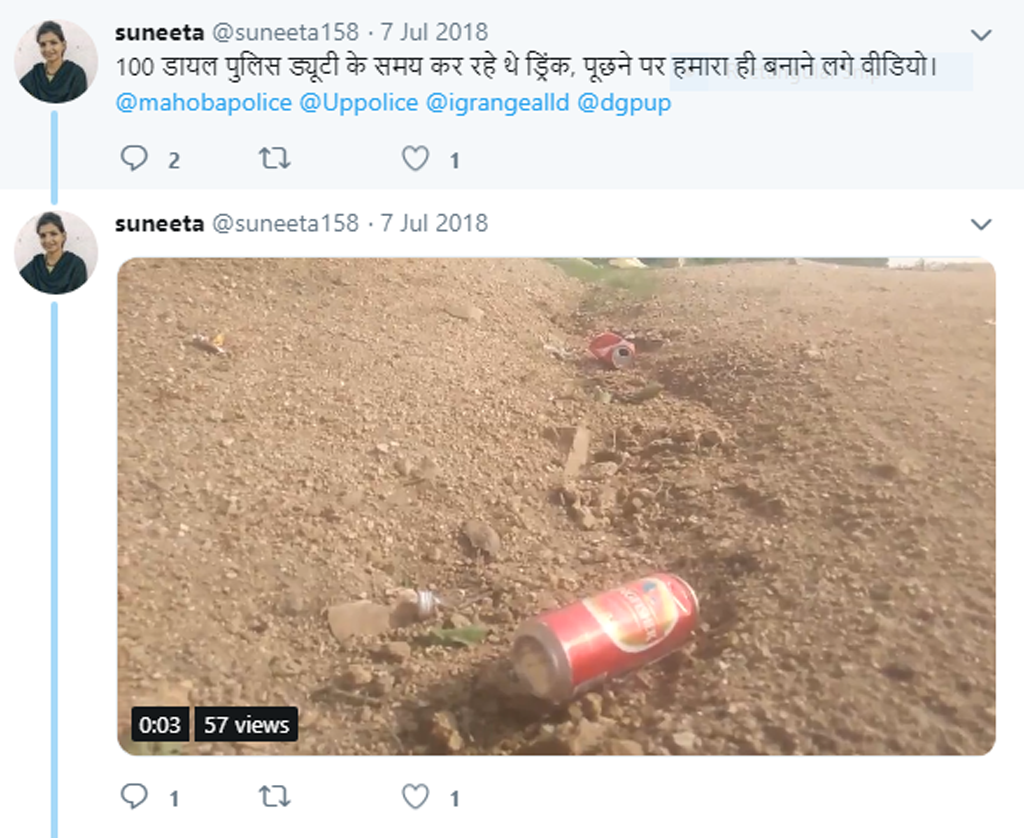

I do feel that if there’s some issue or problem, or something distressing that you share online, then there is definitely a reaction. For example, if I tell you about my friend, who was violated by someone – actually, she was in a relationship with a boy, but then they broke off because of a third person, and things got ugly – she tried getting justice for her case. Lekin sunvai nahi ho rahi thi (She wasn’t being given a fair hearing). But when she put a post on Facebook, many people joined her there, supported her, and there was even legal action.

What is there for her offline? Fear is an emotion exclusive to girls, isn’t it? We know that. But we also know now that fear is not where it ends. And that there are emotions and actions more powerful than fear. We need to know how to summon them.

PP: And this is why you’re on it, why you work it, despite attitudes being unchanged, by your own admission?

SP: Ever since we’ve gone digital and come onto social media, our work is a lot about current news too, the breaking news. We’re more of a competitive newsroom, with very credible social media presence, online presence; people recognise our YouTube channel. So, I’ve had to deal with a lot more people, and in different ways, alag alag tarah se baat karna, jude rehna. Now, I find myself in spaces that require me to mingle and compete, and I do both. Mauke-vardaat par jaana, ghatna sthal par jaana, PC (press conference) mein bhaag lena. So, I’ve deliberately also worked on this gap between the male reporters and myself.

People think that this means I’ve changed as a person or something – that I’m freer, or more confident. But the change is about going online; it’s about being a part of digital media. The fact of the matter is that that is who I am truly, and it’s only expressing itself now. Agar main logon se khulkar baat nahi karungi, toh log bhi mujhse khulkar baat nahi karenge. Kaise patrakarita kar paaungi phir main? (If I don’t open up and speak, how can I expect people to communicate freely with me? And if they don’t, it’s the end of me as a reporter).

If I’m open to information and people, it will be good for my work. In the last one year or so, I would say, this has happened. Mera nikhar ho raha hai.

SP: Yes! I love my work. And I can never do boring work. It can never become a job-job. Khabar karni hai, isliye nahi (Not because I have to)… It should be that I’m having fun; it’s a lark getting information out of people and getting my story straight. If I don’t have the information, I may have to speak with 10 people, so it should be fun, right?, speaking to those 10 people, and not a drag. It should be an easy relationship with everyone – logon ko yeh bhi na lage ki main unse kuch khured rahi hoon, aur yeh bhi nahi lagna chahiye ki main toh kuch zyaada hi free hoon – that’s how I’ll work, that’s how I work.

Read for Part I of this conversation.

Suneeta Prajapati, 24, is a reporter at Khabar Lahariya. She is from Mahoba district, around 100 kilometres from where Khabar Lahariya first put down its roots. Her family lives at the edge of a stone quarry, her village is coated with a thin white dust that comes from the continual blasting and from crusher machines. Her sister, like many others in the region, died of tuberculosis when she was young. Suneeta herself worked in the quarry as a young girl, putting herself through school with the money she was able to earn. She joined Khabar Lahariya in 2012, as an 18-year-old. Over the years, Suneeta has taken on the nexus between politicians, media and mining contractors, and tracked the debilitating violence against women in UP, amongst various political stories and reports.

Pooja Pande is a writer and editor with an experience spanning 17+ years of leading various media outlets, including the eclectic and acclaimed art and culture magazine First City through the 2000s where she was Editor. Her books include Red Lipstick (Penguin Randomhouse, 2016), a literary-styled memoir of celebrity transgender rights activist Laxmi, and Momspeak (Penguin Random House, 2020), a first-of-its-kind feminist exploration of the institution and experience of motherhood in India. Her passion for intersectional feminist revolutions led her to Khabar Lahariya in 2017, where she worked in editorial, outreach, partnerships. She is today Head of Strategy at KL’s mothership, Chambal Media.