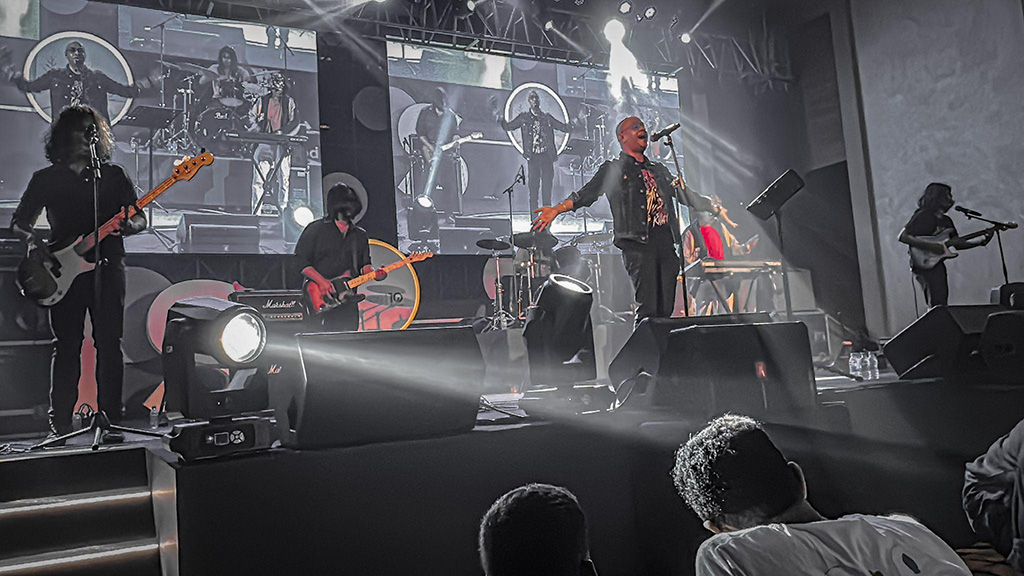

Of course, it was the perfect beginning: a group of deaf children showing off some exceptional drumming, and that too related to Carnatic classical music.

For the performance, the kids, from C.S.I. Deaf School, Chennai, had trained — with the help of sign language — for six months under Suresh Vaidyanathan, popularly known as Ghatam Suresh. Suresh, who himself had suffered torment and bullying as a polio-affected child, guided the children not only through different beats but also tonal differences, with crucial pauses between the beats.

As he said, “I thought they were deaf and mute till I was told they did not speak because no one spoke to them.” Fittingly, the next performance was the konnakol, where the percussion cues are vocalised. A sizzling jugalbandi followed with Suresh on the ghatam and Chandrajith Durairaj on the tabla, after which the audience was invited to clap along with the young musicians. No surprise that our timing was hopeless: the kids were far better than us.

This recital inaugurated the 10th (in-person) India Inclusion Summit (IIS), an annual event in Bengaluru, celebrating diversity and inclusion. The hall, as usual, was packed on November 12, 2022, particularly after the two-year pandemic-enforced hiatus, during which the event was held online.

Welcome November

“Everyone is good at something.”

IIS “is a love fest,” according to its founder V.R. Ferose, senior vice-president and head of the SAP Engineering Academy, Palo Alto. Himself the parent of an autistic son, he is active in the field of inclusion, and is there every year, energising the packed venue, taking the stage at intervals, and finding the time during the break for everyone who wants to talk to him and take selfies.

“I’m too small to deserve so much of love here,” said Ferose, when he took the stage. A while back, he said, he was talking to a friend and asked her, “How are you doing?” She replied, “Not good.” Her younger brother, who had a disability, was no more. “‘I haven’t left my house in six months but I wouldn’t miss IIS,’ she told me.”

That is the power of this annual event.

The summit took off way back in 2012 and Ferose credits its conception to the time he hosted a book talk on Arun Shourie’s Does He Know a Mother’s Heart? Shourie’s son has cerebral palsy and the book had caused some controversy by questioning various religions’ take on disability. Shourie told him, “The best narrative is in Buddhism,” adding, “Never serve with a long face.”

“Change the narrative,” he told Ferose. “Create a platform and let it be the best in the world.” This led to the idea of the India Inclusion Summit.

“At first, I thought it would just be in a small conference room. There was no office, no payroll; only volunteers who care. People can find purpose through others’ pain,” said Ferose.

As parents of an autistic son facing increasing exclusion and isolation, we as a family were in a bad place, tail-spinning into depression. Rahul had missed all the usual markers like a steady career and a steady partner and the pressure on us was immense. Both his father and I junked our careers to focus on our high-functioning, gifted child till he was picked up by SAP Labs under its Autism at Work (AAW) initiative.

The backstory

There is a backstory to AAW. Ferose was leading a perfectly charmed life not too long ago. He had great parents who loved him and instilled in him the right values. At 32, he was the manager of a global entity and a media darling. “The media loves a young guy doing well!”

He had married his college sweetheart and they had a beautiful baby, a boy. Life was good, as he put it. It all changed in June 2010. He was dining with his CTO when the latter observed that the toddler, at 18 months, was not making eye contact and advised Ferose and Deepali to check with a doctor.

After eliminating speech and hearing disabilities, three months later, Vivaan was diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum.

It was the first time Ferose had heard of autism and so he asked for details of the cure, only to be told there wasn’t any and it was a lifelong condition.

“On the way back, Deepali and I didn’t talk in the car. When we got home I went to the bathroom, locked myself in and cried for 30 minutes.” Long days of despair, denial, negotiation and depression followed.

And then, a phone call changed his life. Former IPS officer and social activist Kiran Bedi, a good friend, called him asking why he wasn’t responding to her messages. When he poured his heart out, she said he was lucky because many people struggle for a purpose in life but here “the purpose has found you”. Use your intelligence and network and drive the change, she advised.

He has been doing exactly that since. His mission has been both difficult and fulfilling. He met several parents sharing the agony of having disabled children. One parent told him all he wanted was to live one day longer than his son so that he would not fear for the boy’s future.

Livelihood was another issue. Nearly 64 percent of persons with disabilities in India don’t have jobs, and more men than women have jobs. The recruitment system looks for two things: communication ability and being a team player. “This is not fair.”

And then he heard of Specialisterne in Denmark. The firm had 100 employees, of whom 80 were on the autism spectrum. He met its founder, Thorkil Sonne, whose son was autistic. Mr. Sonne was in a position to know what exactly worked for the young man and others like him and had started the company, tapping into the employees’ special skills. And clearly, it was viable.

A project is born

In less than a year, it was found that three new autistic recruits, without a college degree, produced better output than engineers.

Not alone

Our life changed when our son became part of SAP Labs’ AAW. For the first time in his life, he was treated as an equal. He did not have to mask his disability as many autistics do, at least not at work, and we breathed a little easier. Even then, we still lived in our own silos, not really paying attention to other differently abled people. Until we attended IIS 2015. The atmosphere was electric, full of laughter and crackling with positivity, a far cry from the weepy tropes associated with persons with disabilities (PWDs). If sections of the audience were talking non-stop, unmindful of their levels of disability, the speakers were inspirational. We listened to Simon Baron-Cohen (yes, Sacha’s cousin), the British clinical psychologist and an authority on developmental psychopathology, director of Cambridge University’s Autism Research Centre.

The challenges faced by people on the autism spectrum in the West, I realised, were more or less the same as here.

I then realised we were not so alone.

If Baron-Cohen represented those working in the field of disability, a thrilling talk by Bhavesh Bhatia, a sighted man who went blind, rid me of all self-pity. Here was a man who didn’t let a sudden downturn in fate stump him. Instead, he resolutely set about carving a career for himself by making candles. He soon floated a company and became an exporter. Today, most of Sunrise Candles’ staff is visually impaired.

That set the tone for the day. There was adman Prahlad Kakkar gleefully talking about his learning disability and para athlete Deepa Malik throwing him a challenge to hire her for his next campaign. Patu Keswani of Lemon Tree Hotels spoke of his commitment to hire the differently abled as much as possible.

We went home, overwhelmed.

The next year, at the end of IIS 2016, we were inspired by the differently abled who sang, danced, spoke and battled their way through life with grace, guts and good humour. Helping spread the inclusivity message were the likes of author Amish Tripathi, Youth4Jobs founder Meera Shenoy, Goonj founder and Ramon Magsaysay awardee Anshu Gupta and paralympic gold medalist Mariyappan Thangavelu.

A senator and his brother

IIS 2017 hosted Democrat Senator Tom Harkin, whose brother’s hearing impairment — and the usual discrimination — led him to push through the Americans with Disability Act of 1990, one of the earliest legislations in support of disabled people. Ed Kennedy’s successor to the Iowa seat took a flight to Bengaluru and was ferried “in a Maruti Alto” all over the city. “Nobody in the government knew he was coming and when he went to the Vidhana Soudha, all meetings stopped,” chuckled Ferose. The soft-spoken senator, at the IIS summit, cited instances of how, by helping the disabled, everyone in the community could benefit.

For example, film subtitles, which we now take for granted, began as a service to the hearing impaired but everyone took to them, particularly when accents were difficult to follow.

This edition also showcased a host of technologies and technocrats working in the disabilities field.

The pandemic forced a hiatus to in-person IIS though the star cast were available online. One of them, of course, was actor Sonu Sood, whose altruism made the headlines during that tragic time.

So, it was thrilling again to meet friends and new faces in 2022. The comperes, as in past summits, were persons with disabilities (PWDs). Soumita Basu, founder of Zyenika Inclusive Fashion who took the stage, designs adaptive clothing. She described how she, while in hospital herself, modified a uniform for a young boy. His mother had called her saying he was refusing to go to school because the uniform made it difficult for him to use the bathroom. Soumita pulled it off. She also crafted a pair of jeans for someone with cerebral palsy. Another PWD told her she felt sexy in her modified dress and was ready to date. Soumita, who has faced comments like, “You don’t look disabled enough,” said her motto is, “Do what you can with what you have.”

And then there was the playback singer, Jyothi Kalai. She is both blind and autistic. Her mother Kalaiselvi’s determination and support have seen Jyothi win several awards and a big fan following. She even has students from the US and UK. “Next year I am going to America and UK,” Jyothi announced excitedly, after playing two numbers, one vocal and the other on the violin.

The other compere at the event was Tiffany Brar, founder of the Jyothirgamaya Foundation that teaches life skills to blind people. Winner of the IIS Fellowship, she spoke of the discrimination she faced at school, including from the teacher herself. After changing schools, this steely, young woman ended up topping the CBSC exams. Her work, which includes mobile blind schools, won her the Nari Shakti Puraskar from then President Ram Nath Kovind.

Missing an arm. Or not

Rishi Krishna was going from Chennai to Puducherry by bus when it crashed and he found himself in hospital, minus his right arm. He was just 24. Four years later, the wannabe filmmaker and social worker heads a tech company that makes bionic arms.

“Why are our prosthetics 200 years behind times?” he asked.

So, he and his friend Niranjan started Symbionic. “We began with one arm and now we’re going to make a million,” he said, referring to the lakhs of amputees in India. There were 25 iterations (“25 failures; you should have seen the first, full of hanging wires”) before Titan Arm became marketable. “We have 15 people working on the product. It is so cool that even able-bodied people would want to wear it!” He is proud of the fact that while an imported bionic arm would cost around Rs.50 lakh, his is a fraction at Rs.2.5 lakh.

Art and IIS

Art is a crucial part of IIS and Vicky Roy, who has gone around the country taking photographs of PWDs across the country, showcased some of his photographs at the event. “Like Humans of New York or Humans of Bombay,” he said. “I have 89 stories from across India, covering 18 types of disability.” He has to do three more to reach his target. What was particularly fascinating was that the photographs also had tactile versions alongside to enable visually challenged people to appreciate them. The stories are all there at https://www.everyoneisgoodatsomething.com, which he said, “has no ‘like’ buttons because all stories are good stories”.

A great outcome has been that some of the PWDs he has photographed have been contacted by those who want to pitch in by way of money, wheelchairs, electric sewing machines, laptops and even cricket balls.

IIS Fellowship

A key aspect of the summit is the Inclusion Fellowship that provides capital in the form of knowledge, compassion, technology, network, and support for young entrepreneurs working in the field of disability and inclusivity. The Inclusion Fellows, according to Ferose, are the problem solvers and doers. They are dreamers who have “the right mix of idealism, passion and compassion”. He expects that in two decades, these Fellows would have made enough difference to make the world a better place for everyone and that “our task is to hold [their] hands in their journey”.

Unsung hero

The one who started it all, Vivaan, is 13 now and his primary caregiver is Deepali. Ferose says she has always been far more intelligent and hardworking than he was. “I was the backbencher.” After Vivaan’s diagnosis, she quit her job to look after him after telling her husband, “I will change Vivaan for the world; you go out and change the world for Vivaan.”

IIS is entirely volunteer-driven and it was these volunteers who came to the rescue of the disabled during the pandemic. Covid-19 was disastrous for the disabled community. Many lost their primary caregivers. But hundreds of volunteers kept in touch with them every day. “There are different forms of currency: joy, happiness, compassion. Every volunteer is a leader,” according to Ferose.

It was here, at IIS, that I first pushed a wheelchair, occupied by a cheerful young man who told me matter-of-factly he had multiple sclerosis and had taken to the wheelchair two years prior to our encounter. Vijay and I have become good friends and he has become a brand ambassador for wheelchair sports.

I saw a sassy young woman, part of whose limbs were eaten by bacteria, tackle life with enviable guts.

I saw young volunteers, despite deadline-driven careers, give their everything to make the event rock. I met well-wishers who sincerely want to make our world a more compassionate place. I have spoken to families who have stayed with and continued to love their children and siblings gifted with different abilities. I was inspired to watch talks and read books by experts so that I could understand and appreciate my own son’s unique perspective of the world, full of empathy and devoid of malice and one-upmanship. I appreciate that he does not own a vehicle, preferring to walk or take the public transport. He is unimpressed by consumerism and his lifestyle qualifies him to be a poster boy for climate emergency activists. Sometimes, when his parents give in to cynicism, he shames us with his philosophical outlook. He has immense compassion for those who struggle in life as well as animals. (Cockroaches are an exception though!)

Today, we as a family have rediscovered our ability to dream and hope. We now see the differently abled as our own. We and ours are like the diverse gems on navaratna jewellery, each mismatched stone polished in its own unique way but making a splendid, iridescent whole.

A version of this article first appeared on the India Inclusion Summit Blogs.