In 2013, Nirantar produced a short documentary on the non-binary experience in schools. Featuring Nrrups, Sunil and Rajarshi, the film travels from Kolkata to Bengaluru to Thane to meet people for whom school was the brutal part of their childhood.

A decade later, the author — a researcher and trainer — watches the film and contemplates the limitations of visibility in reducing violence and increasing inclusion for non-conforming persons. Instead, the author proposes, the answer may just lie in proximity.

In one of the scenes in Bioscope, Sunil from Bengaluru recalls how they were always taunted about walking boyishly. “I started thinking, what is boyish about this?”

I knew exactly what Sunil was talking about. It was a familiar cluelessness.

I could make good friends with girls, but when I joined high school for my senior secondary education, I abruptly stopped talking to all my girlfriends. “I don’t want my name linked with any girl,” was my perpetual answer to anyone who asked why I didn’t talk to the very girls I had studied with for nine years. I have thought about this again and again. The more I thought about it, the clearer the answer became.

It was fear.

One is kept in fear in subtle and intimate ways inside educational institutions.

Entry (if, as a trans person, you could gain entry) into an educational space (school, college or even university) immediately makes you experience segregation. It starts with the prayer session queues, goes on to classroom seating arrangements, and magnifies during the work division in school functions and festivities. The fact that schools are non-transgressive is sculpted into uniforms, toilets and hostel arrangements.

The slightest deviation from the neat segregation of boy-like and girl-like invites punishment. People raise eyebrows and exchange smirks when the ‘deviant’ passes by. They laugh, point out the problems, and try to make you a ‘normal’ man or woman, sometimes through what they undoubtedly consider sage advice, but primarily through shaming. The punishment takes the form of bullying and physical and sexual violence as well.

I was afraid that my proximity to girls would make my femininity palpable. So, I stayed away from them.

I was in primary school. My second standard teacher, in one of her classes, demonstrated how each of us walked. There were occasional giggles, but we were mesmerised by how well she emulated our gaits. When she was about to demonstrate my walking style, I felt a flame of heat behind my earlobes. The entire class burst into laughter seconds after she walked like me from one end of the class to the other. I laughed with them.

I learnt three critical things that day. What about me could generate laughter, what I need to do — to give up — to stop that laughter, and most importantly, I learnt that shame comes not only through aggression but also in various forms and degrees: from casual laughter to severe admonishment.

One learns to anticipate the shame. It turns into reflexes; being silent in the right conversations, being absent from the right places and adopting the ‘correct’ behaviour. To survive, either you minimise your deviation from the binary or conform to it in every possible way. Not obeying the norms of the gender binary even becomes the reason for being pushed out of educational institutions. To exist in schools — which is a fundamental and universal right according to Article 21 of the Indian Constitution — becomes a negotiation and real-time struggle for non-binary and transgender students.

In high school, I stopped shaving my beard. I stopped sitting with crossed legs. I consciously put effort into walking like a man. I never used certain words and expressions while speaking that everyone considered womanly.

I was moving mountains to undo my femininity.

School taught me to camouflage.

In Bioscope, Nrrups, a trans man based in Thane, recounts, “When it comes to toilets, it is the same situation. When I would go to the girls’ toilet, they would say, you have to go to the boys’. Because they could not tell that I am female. It would just lead to fights. I went to the principal along with some of my friends. And the principal was quite supportive. She said that you have to believe the student and not interfere with his or her personal life and choices. But I always had fear in me. Sometimes, I used the boys’ toilet. But I would have to wait all day for college to end before I could use it.’’

My high school did not have toilets for boys so the boys used the bushes nearby to pee. I used to get anxious every day as soon as the first two periods were up and we had a short toilet break. A mix of distress and unease would creep over me. I would look for friendly company or wait for the right time to dodge the crowd while I could pee.

Isolation, loneliness and silence are some of the other recurring words that Sunil and Nrrups choose to describe their childhoods in schools. More or less, every other non-binary person in school would use the same words.

A close friend who was also my schoolmate requested that I maintain some distance from them in school: that we remain as close but keep the friendship discreet on school premises. After their request, I consciously made an effort not to be seen around that friend.

In school — for that matter, in any educational space — it was not only me who would think multiple times before entering a space, striking up a conversation, or making effort to build friendships. Even those who conform to the binary also contemplated before making that effort to be friends with a non-binary person.

When I say schools teach binary spatially, this is what I mean. Educational institutions activate reclusion through sheer elimination. They achieve it by creating identities and then by putting mechanisms in place that deny proximity between those who don’t conform to created identities. These mechanisms leave no room for any other imagination of trans people; that we have hobbies, we have favourite songs to groove to, that we gossip, that we, too, could walk on the street lost in thought. We have joys. Our tragedies achieve grandeur, but the

imagination that our life could also be mundane is not permitted.

In 2015, I was in my undergrad at a reputed state university in Bhubaneswar. In the same year, Manobi Bandyopadhyay took charge as the principal of Krishna Nagar Women’s College in West Bengal. As usual, the “First Trans Woman to …” news was all over national and regional dailies. One of my professors, famous on the campus for being jolly and student-friendly, cracked a joke looking at me. “Nowadays, your kind are becoming deans as well.”

Indeed, the news was reassuring for many trans people. But the effect of that visibility was not uniform. In current times, when I see ‘visibility’ occupying the centre stage of trans-political imagination to make educational spaces inclusive, I often wonder about the limitation of this framework. The professor at my university did not have a clue what impact that piece of news had on me, and on many non-binary people in universities across India. Because for him, it was a reality, but a distant one without any proximity.

During my post-graduation in gender studies, I was the only visible transgender person. My visibility made me a ‘trans-life journey’ expert everyone wanted to pay attention to. But that did not make the campus immediately transgender-inclusive. It did change a few things; the discomfort at the sight of my existence mellowed. But I don’t think that made anything easier for the non-binary students who joined the institution in the subsequent years. They must have repeated the same visibility routine unless they were the same kind of trans, exactly like me.

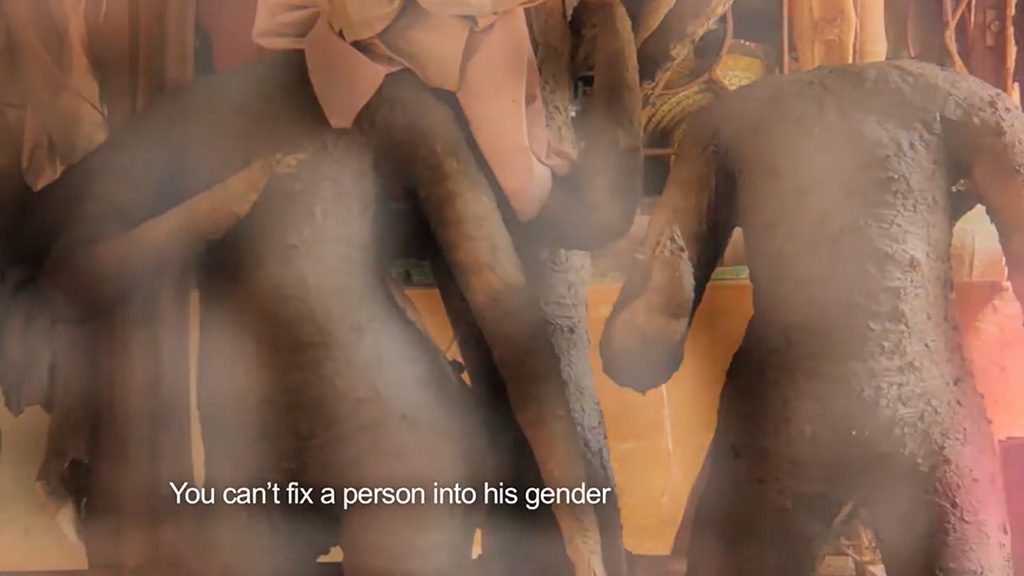

Over a period of time, I have realised visibility definitely disrupts the visual grammar of the gender binary in educational institutions, like it would do in any space whenever a trans person asserts their gender expressions in ways that are not conformist. But visibility does not dismantle the estranged feeling between the so-called normal world of the binary and the non-binary world.

Because visibility becomes optics bound — that trans person who dresses differently.

Because it becomes speech bound — the trans person who comes out.

Because it becomes proof bound — the valid trans person with accurate documents.

The decades-long work of feminist thinking has made it possible for us to recognise that education spaces uphold, maintain and reproduce the norms of the gender binary. Historically, curriculum, pedagogy and the attitudes of educators and peers have been the primary sites of feminist intervention. Reform in all three areas has been the main agenda of the advocacy for gender rights groups. Cultivating gender sensitivity among educators and peers through gender sensitisation training, along with creating gender-responsive curricula and pedagogical tools, have been crucial to attack the structural basis of gender.

But learning gender binary in schools is not limited to curriculum and classroom pedagogy. Neither is it limited to the individual behaviours of teachers and peers. School actively maintains gender or, more specifically, the binary of gender even spatially. There are barriers for transgender people to be in educational institutions. The involvement of document bureaucracy is another reason that keeps transgender people from entering into education space without the correct gender put in the ‘gender column’.

Hence, making classrooms and campuses inclusive cannot only be about behavioural change models that do not involve proximity. The syllabus, curricula and the attitudes of peers and teachers cannot be the only site of intervention because this intervention imagines non-binary people only as students. This reflects creative bankruptcy. Could trans people exist in an educational institution only as students?

I do not think so.

We could be teachers.

We could be in the administration.

We could also be the support staff.

Behavioural change and curriculum reform as standalone interventions without addressing the question of accessibility are not effective. Because then the onus of change is solely about our discrimination and our hurdles. Our discrimination becomes more important than us.

In other words, our tragedies become us.

“I came across Debdas and his group of seven to eight kids. I knew by looking at them that they are also kothis (like me). They also faced discrimination. So, I knew something had to be done. So, my first step was to make them comfortable with themselves, that whoever you are is fine,’’ says Rajarshi in Bioscope, who taught Debdas in school. Debdas says with a glowing smile, “After we became closer, Rajarshi made me his daughter and I call him my mother.”

That smile on Debdas’s face, and more so the relationship between Rajarshi and Debdas that bloomed in an educational space, also allows the cynic me to imagine ‘proximity’ as a pedagogical and spatial intervention. Proximity might not abolish the gender binary, but it might allow for the possibility to hold and share mundane existence of non-binary people. It might be a provocation to the structures of binaries in ways that might open up avenues to discuss the immateriality of maintaining the same binary in our political imagination. It might create a space where non-binary people can enter and are not just seen in the transaction of our visibility, where we are not treated as agendas of inclusion but rather where the ordinariness of our lives could be acknowledged, and we are known as individuals with complete personhood.