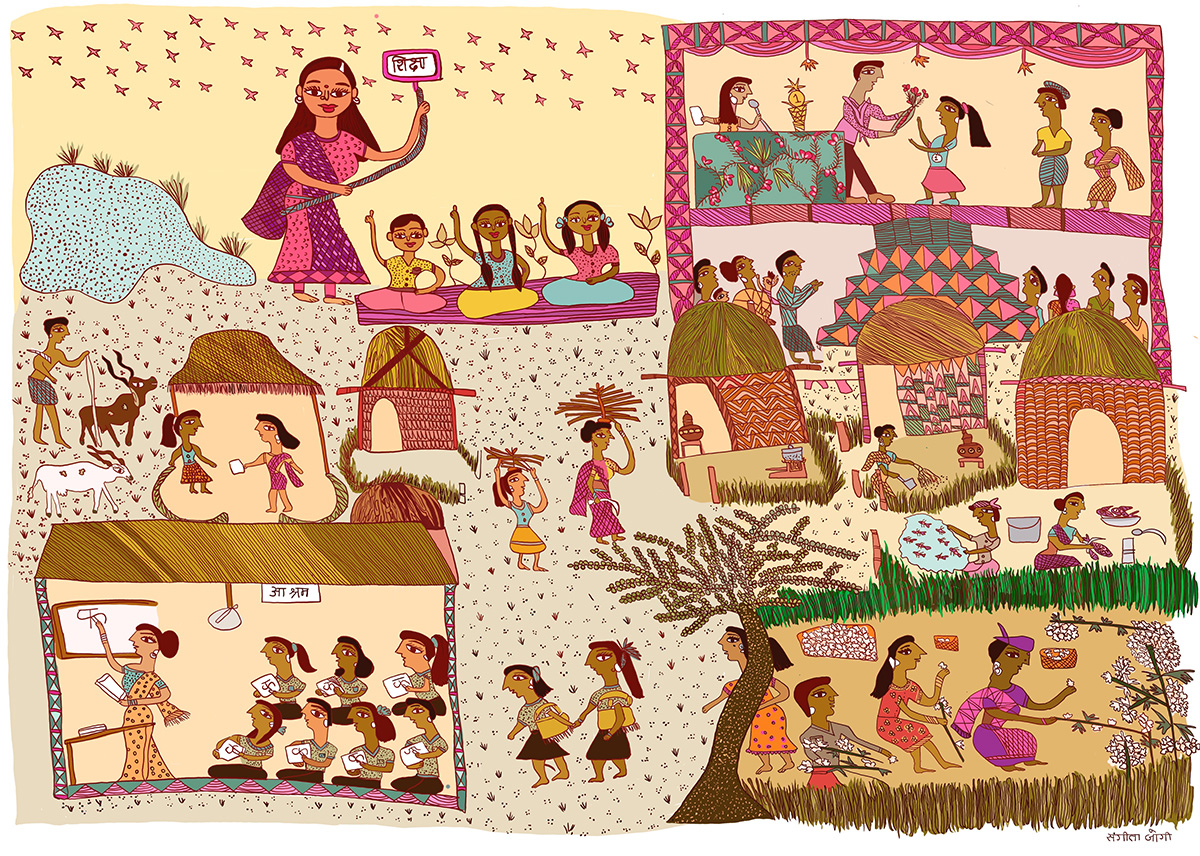

Durga Masram has participated in the EduLog programme with The Third Eye for its Education Edition. The EduLog mentored 12 writers and image-makers from India, Nepal and Bangladesh to remember—in the present continuous—their experience of education from a feminist lens.

I was born in the Gond Adivasi community in Wardha, Maharashtra. I am the eldest of my siblings—three sisters and a brother. My parents are farm labourers who work in fields that belong to other people. Yet, they never held back and gave us the best education that they could. Today, I am in Mumbai, a city that my parents have never seen and that is only a name to them. I came here alone and have secured admission at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS).

The journey from a village to TISS was not an easy one.

What is education in a place where people are looking for only two square meals a day?

A place where after working for the whole day, a man earns Rs 300 and a woman Rs 100. When I was in Class 6, the remuneration was Rs 25 for women and Rs 100 for men. We were in dire financial straits at that time, and I too worked in the fields from 6 am to 9 am, for which I used to get a wage of Rs 7.50. After that, I went to school from 11 am to 6 pm. By the way, work was not always available. It depended on the season. Most often, work meant picking cotton or weeding. Often, instead of going to school, I had to go and work in the fields the whole day. When I saw children from my school pass by, I would hide so that they would not tell the teacher. Of course, many times the children did see me working and would threaten to tell the teacher. I was always scared.

I was not weak in my studies. In fact, I was good. I stood first in class 5. Even though I was living at my maternal uncle’s house and had to do all the housework, I did well at school. Eventually, housework and working on the farm became part of my daily life. Not only did I work on weekends, but I also worked on weekdays. But after class 5, I gradually became weak in my studies. I could not manage everything together.

I was the first girl from my village to go to study in an Adivasi hostel. Before I went there, the people of our locality believed that if girls went out to study, they would run away and get married. That’s why they didn’t allow their girls to go to hostels. After I went, people understood that girls do not run away if they are allowed to go and study. Their thinking began to change slowly. After seeing me, girls from my area gradually started coming to study in the hostel. Unfortunately, our parents were not educated and we didn’t have the ambience for studying at home. And because we did not understand the importance of education, we didn’t really study in the hostel either. We didn’t know what we could achieve with education, and nobody told us. This is the reason why some girls dropped out very early, some took up government jobs and many became domestic workers.

I was interested in reading. Seeing me read, my friends would say, “Will you become a collector by reading so much?” They teased me and undermined my confidence. But I too would join in their fun. We felt that it was okay to study just enough to pass the exams.

Had the importance of education been explained to us in Adivasi Ashram schools and hostels or had our teachers told us the importance of education and what we could achieve with it, then many girls would have done a lot more in life.

Gandhian social worker, Thakkar Bappa started the first ashram school in Meerkhedi, in Gujarat for those who were not integrated into the mainstream and were living in remote forest areas. Adivasi Ashram Shalas and hostels have played a big role in helping tribal children access basic as well as higher education. Ashram schools offer education to children from Class 1 to 12.

I often think of how the word ‘ashram’ is itself embedded in the Brahmanical tradition. Tribal children studying in ashram schools are bereft of their language and culture. Most Adivasis are nature worshippers. In the hostel, they learn to worship Durga, Krishna, Ganpati and other Hindu gods and goddesses. The hostel where I studied used to bring in Lord Ganesh every year. Ashram schools and hostels play an important role in alienating us from our Adivasi identity. Tribal Christians go to mission schools and lose their identity there.

We don’t learn the history of our people. Many great Adivasis who laid down their lives during the independence movement—Rani Durgavati, Birsa Munda, Tantya Bhil are never even mentioned in school curricula.

We don’t learn our language either. We speak Marathi, the local language here. Some people know our Gondi language, but not the younger generations. When these children grow up, they can only pass on what they learnt to their children. They lose their own culture and identity because they are only taught about mainstream culture.

Then there is the matter of our appearance. I’ve seen a lot of discrimination between dark-skinned and fair-skinned people. My grandmother’s complexion was very dark. I asked her “You are so dark; didn’t you have any problem with marriage?” She said, “We did not have any problem. This discrimination based on skin colour is recent. We lived in the forest, where we never saw any such discrimination.” But discrimination based on colour is clearly visible in our village today. Every boy, regardless of his own skin colour, wants a fair bride. When I was in class 3, a boy told me that I should have been named Kali and not Durga! Women from the neighbourhood would tell my mother that it was going to be difficult to get me married as I was dark. They used to say that I should have had my brother’s complexion and he should have got mine!

Discrimination on the basis of my colour slowly caused self-doubt and low self-esteem in me. Despite being a good speaker, I never had the confidence to go up on stage. Once there was a debate competition in school. The boys in my class teased me, “Oh what speech will she give?” I felt bad, but I also took it as a challenge. The subject of the debate was—The pen is mightier than the sword. I spoke about how writing is powerful and the role it plays in our life. I spoke well and stood first in the competition. Impressed by my speech, the teachers congratulated me right as I came off the stage. Over time, I understood that I was not alone in how I felt and that these feelings were the results of a patriarchal society. I understood this after joining the Department of Women’s Studies of Mahatma Gandhi International Hindi University, Wardha. In a patriarchal society, girls are supposed to be fair and thin. I didn’t fit into this pattern. I always wondered why fate had made me dark and moreover, why I was poor.

Maybe I wouldn't have had such negative feelings if society hadn’t ingrained them in me since childhood.

Back home, our village has different areas demarcated for every caste. The Mahar and the Adivasi areas are located at the end of the village. That’s where we live. The Teli (Vaishya) area of our village is very affluent. As children, we would hanker after their big houses and farms. Similarly, the Brahmins have a separate area. They too have big houses and large farms. We farm their lands. The fishermen and hunters are known as ‘Bhoi’ in the village and there is a separate area for them as well. This is how our village lives, divided and within their own communities.

Earlier, we were discriminated against in this village. We were not allowed to draw water from the well. We had to stand near the well for hours waiting for someone else to come and draw water for us. If no one came along, we had no water and we could not do household chores or go to the fields. My grandmother remembers struggling like this for water, just after childbirth. She had to go to work even when her baby was a few days old.

Then one day, a government official came to the village. We had gone to get water. Seeing us waiting, he asked, “Why aren’t you drawing out the water?” “We can’t.” “Why not?” he asked. “The others don’t drink water that we have touched. They will not like it if we draw the water.” He said, “You draw the water and let me see who stops you.” Since that day, we have been drawing water from that well. I must have been 12–13 years old at that time and didn’t really understand what caste was. I only wondered why they were behaving this way and why they wouldn’t give us water. I was troubled by many such questions.

It was with my education that I understood that I had been discriminated against on the basis of caste.

We, the Adivasis, are now living in a so-called civilised society. We have adopted their language and culture, along with their ethos, and that is why colour, caste and gender discrimination have also seeped into our ethos. I would often ask my grandmother, “Where did we live earlier?” She would say that we lived far away in the forest, but we came to this village because we had been displaced. If the village had not moved, we would have lived in the forest. We had to move from one place to another, sometimes to work on a dam being built or in the mines or in some mill. Many tribals had to abandon their villages to look for jobs in cities.

My grandmother is not with us anymore. We only know what she told us. Our people do not have a written history and that is why the new generation does not know the story of the struggle of our ancestors. The new generation is unaware of how much their families have struggled to maintain their identity. We are losing that identity now. Yes, there are some ballads that have been sung amongst us for generations, and that is the only way to learn about our people.

The issue of language continues to be part of my life. At home, we speak the Gondi language. I did my schooling in Marathi. Then I did my Master’s degree in social work and an MPhil in Hindi. The struggle continues with English in TISS. I did not have many problems with learning Marathi and Hindi, but English has been a different ball game altogether. There was a time when I was afraid of English. There were people at TISS who taunted, “Oho, even those who do not know English also get admission here.” I was passionate about studying, so I did not give up and went on reading. Luckily, I have met many inspiring people in my life. Professor Wankhede at TISS helped me a lot. Other students like Akash Poyam, Saroj and Vishal encouraged me. When I first met my PhD supervisor, Dr Bal Raksha, I told him that my English was weak. He replied “English is just a language. If you work hard, you will learn. If people read for five hours, you will have to read for ten.” That inspired me to continue my struggle.

We, Adivasis, have joined the so-called civilised society, but our social, economic and educational development is still lacking. The country is moving forward and developing rapidly. Digital India is taking shape, but a part of this Digital India is dying of hunger. Leave alone digital, we lack basic educational opportunities. So many of my brethren can’t manage to eat two square meals a day. Will they even think of education?

The Department of Tribal Welfare is supposedly there for our well-being, but very few know about the schemes that are available. These few people take advantage of the schemes, while others get no benefits.

Apparently, there is a lot of funding for tribal welfare, but where does it go? Where does one fill out the form? Where does one submit it? People don’t know.

If we have an education, we can understand a lot of things. Otherwise, we are forced to just listen to whatever people tell us. We neither question them nor do we think for ourselves. Education teaches us to think. It teaches us how to live.

Once people are educated, the way they talk changes completely. Because of this, I also got a chance to contest elections. It was the first time that someone in my family was contesting an election. My father used to work for a gentleman called Bhausaheb Dhanore, and he encouraged me to do this. I can’t forget the respect my family got after I contested the elections. My father got a lot of respect, and we got the chance to sit with renowned people from the village. Education is very important in life. It changes one’s life. By contesting the village elections, I wanted to encourage girls like me; so that someday the history of our Adivasi society can also be written. And hopefully, my name will be recorded in it as an educated leader.

This article has been translated by Maneesha Taneja. She works as Associate Professor at Delhi University.