Feminist economists had long focused on time as a measure of work, or more specifically, as a measure of enumerating women’s work, even before we zoomed in on the endless time and labour women continued to expend on doing, doing, doing as the world ‘stayed at home’ during the pandemic.

Also coinciding with the pandemic were the results of the first-ever All India Time Use Survey (TUS) conducted from January to December 2019 by the National Statistical Office (NSO). The TUS recorded how men and women across the country spent their time in the 24 hours from 4 am on one day to 4 am the next. The survey, covering 4.5 lakh Indians (of the age 6 years and above) in 1.4 lakh households, found that if unpaid labour was taken into account, 95% of women and 85% of men worked. The survey also maps the time spent on leisure, self-care and maintenance, socialising, and learning, among other activities.

Crucially, behind this year long survey lies nearly five decades of feminist struggle to visibilise women’s work. The TUS underscored what feminists have been urging us to look at all along — millions of women work but go missing in national-level surveys as their work is mostly not counted either by their families, communities or even the state: in short, unrecognised in everyday life.

In 1982, feminist economists Devaki Jain and Malini Chand published the first Time Allocation Survey (TAS), as it was called then, from data they collected in West Bengal and Rajasthan. They argued that to properly capture and enumerate women’s work, there was a need to rethink the idea of work and use time as a means of capturing this work. This meant that there was a need to first look and list all the activities undertaken by individuals and then to group productive and non-productive activities to “arrive at a wider definition of gainful activity” (gainful activities refer to those activities that are seen to have economic worth).

As Jain wrote in her 1996 paper, Valuing Work: Time as Measure, “If women’s unpaid work were properly valued, it is quite possible that [they] would emerge in most societies as the main breadwinners – or at least equal breadwinners – since they put in more hours of work than men…”

Invisible work

Traditional survey methods render work done by women like processing paddy or taking care of a child as non-work or “as supplementary, subsidiary or secondary” work. Unlike traditional surveys, TUS interviewers ask respondents to recall what they did in the last 24 hours to track paid work, unpaid work and leisure. As Dr Shiney Chakraborty, research analyst at the Institute of Social Studies Trust (ISST), told The Third Eye, citing the example of women in rural India, “They spend 55 minutes fetching water and spend one hour or so in collecting firewood and if we start including these unpaid activities, it’s not that women are working less in India. It is quite the opposite.” She adds,

“Our surveys are not able to capture women’s work, that is the reason behind the low and declining women worker participation rates in India."

The results of the TUS prompt seemingly basic questions that have quite complex answers — what do we consider work and why?

As a child, I’d write in my school diary that my mother’s occupation was ‘housewife’, despite knowing she taught music to neighbourhood children on alternate days and worked as a part-time arts and crafts teacher at school. Another friend did the same even though her mother sold jaggery and stitched sari blouses for her friends in the summer. When asked, my mother would say that her job was to take care of the household and us. Surveyors asking women what work they do, run the risk of their citing one specific activity while they do multiple things in a day. Due to the conditioned understanding of work as something that is paid, more often than not the usual answer would be, “I don’t work.”

Dr Ashwini Deshpande, founding director of the Centre for Economic Data and Analysis (CEDA) at Ashoka University, has written about the importance of time use surveys in India, specifically where women do unpaid economic work such as on family farms and family-run stores. She also argues that this work would be of a paid nature if done by a man. She adds, “Time use research served the purpose of drawing attention to the multiple demands on women’s time. Researchers have been using this data to calculate the economic costs of women’s unpaid domestic work.”

The TUS 2019

In sharp contrast to the 2019 TUS, The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) of 2018-19 recorded the female labour force participation rateat a mere 18.6%. . .18% vs 95%. This gap appears because of biased methodology and enumeration in traditional surveys that continue to discount women’s unpaid labour.

The TUS 2019, as Chakraborty points out, also reveals that women spend six and a half hours a day on unpaid labour compared to men’s two and half hours. Women spend five and a half hours on paid activities compared to men’s nearly six and a half hours. Women spend 17% of their time on unpaid household chores and caregiving activities compared to men’s 7%. Men also get more hours for self-care, maintenance and learning than women.

The survey, despite its many criticisms (more about which later), has many strands of possibilities — in policy, employment and importantly in nudging a shift in our discourse about gender and labour. As Prof. Indira Hirway, Centre for Development Alternatives (CFDA), told The Third Eye, “The Time Use Survey helps in capturing informal labour or simultaneous activities, reveals the gender inequalities in paid and unpaid work, gives you an idea about time poverty and work-life balance, and tells you details on home piece-rate workers.”

Women often engage in simultaneous activities like, say, making packets of bindis at home while performing care activities such as looking after children or aged relatives and the TUS methodology brings attention to these multiple forms of labour. As Jain wrote in her 1996 paper, their labour is largely concentrated in work that is “the least skilled, worst paid, most time-consuming ones”.

The TUS is particularly important for understanding time poverty. In her essay Understanding Poverty: Insights Emerging from Time Use of the Poor, Hirway writes, “Time poverty is understood in the context of the burden of competing claims for the individuals’ time that reduce their ability to make unconstrained choices on how they allocate their time, leading frequently to work intensity and trade-offs among various tasks. Time poverty is seen as a time burden on the poor, particularly women.” Women’s daily tasks include household work, care work and reproductive work to sustain their families. All this combined leaves them time-poor.

And, as journalist Rukmini S writes, the TUS 2019 also recorded how caste, class and geographical location intersect with labour and leisure.

The survey found that upper caste women spend the most time on unpaid work. Upper caste men spend the most time on leisure while women belonging to scheduled castes and scheduled tribes had the least time for self-care.

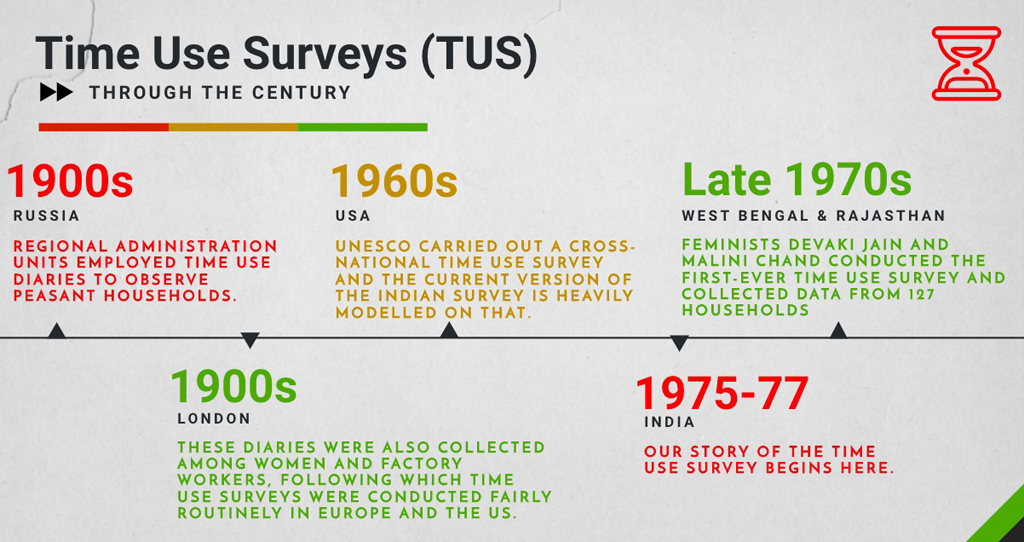

According to Ashwini Deshpande, the first TUS dates back to the 1900s in Russia where regional administration units employed time use diaries to observe peasant households. These diaries were also collected in London among women and factory workers during the 1900s. Following this, TUSs were conducted fairly routinely in Europe and the US. In the 1960s, UNESCO carried out a cross-national TUS and the current version of the Indian survey is heavily modelled on that.

Our story of the TUS in India begins in 1975-’77. Feminists Devaki Jain and Malini Chand ambitiously set out to conduct the first-ever survey. They collected data in 127 households in West Bengal and Rajasthan in the late ’70s. The results, published in 1982, found significant women and girls’ work participation in tasks like cutting grass and cattle grazing in Rajasthan. Certain tasks done by women in West Bengal like prostitution and working as domestic help were invisiblised. They also found the presence of children between the ages of 5 and 14 engaging in gainful agricultural activities such as girls threshing and winnowing and boys hoeing the fields.

Jain told The Third Eye she wanted to rectify the NSSO data on female work participation and count the women who contribute to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Why did she? There was no particular trigger, just a feeling it would be good to see how much time was spent on “economically productive work and how much in private [time spent on other activities outside economic activities], that would be a good way of counting, identifying the worker.” She approached the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR) and DD Narula, the then-member secretary, approved the project and sanctioned the funds.

Along with the help of the NSSO staff and the support of the then-chairperson VM Dandekar, the Time Allocation Survey (TAS) was conducted. The results revealed that data on female and children workforce participation changed depending on the methodology. The one the NSSO followed had a skewed, patriarchal understanding of work. The TAS was able to capture data from women engaged in groundnut sowing for close to three hours and yet stated that they did no work, or women who worked as part-time domestic help in other houses but reported to the NSSO’s questionnaire as ‘non-workers’. The NSSO methodology rarely probed or asked questions about what exactly the women were engaged in, thereby reiterating through data collection the culturally held view that women’s labour merely ‘supplements’ the family and that it is men who work and are the ‘breadwinners’.

The findings of this pioneering 1975-’77 survey were then presented at the Institute of Economic Growth at Delhi University. Jain recalls how she approached Prof. Krishna who had worked at the World Bank and they organised and funded a Raj Krishna Memorial Seminar. “It blows my mind to think that [prominent Indian economists] Pranab Bardhan, Sukhumoy Chakravarty, Hanumantha Rao, all these persons were willing to come to the seminar and to also contribute their own ideas,” says Jain, tracing how NSSO officials were present at the seminar when the resounding call was made to change how statistics were collected.

Jain and Chand highlighted the pressing need to craft a different method to rigorously understand women’s work as “the obvious inference is that the gainful activity of females and children – the tasks they engage in, or its location, do not get into the net cast by the existing investigation methodology, with the same precision as males.”

Census Lacuna

This lack of precision in methodology found itself in the Census as well. Feminist economist Maitreyi Krishnaraj in her 1990 paper Women’s Work in Indian Census: Beginnings of Change pointed out that the 1981 Census recorded that slightly over 13% of women worked. A piece of data that looked stranger given that the 1988 Report of the National Commission on Self Employed Women titled Shram Shakti found that 89% of women worked in the unorganised sector. The question that was asked in the Census 1981 was, “Did you work anytime at all last year?” and it excluded women as they rarely reported themselves as workers.

A small and significant addition by The United Nations Development Fund for Women (Unifem) project to this question changed some things. Thus the 1991 Census thus asked, “Did you work anytime at all last year? (including unpaid work on family farm or family enterprise?)” This Census found over 20% of women worked — the increase was not much but the addition to just that question broadened the definition of work.

Pilot TUS

After much feminist intervention, the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) set up a committee to carry out a pilot time use survey, two decades later, in 1998 in six states in India. Prof. Indira Hirway — working with United Nations Development Programme at the time — was the head of the technical team and in charge of designing the pilot survey and its implementation.

At a United Nations conference on the time use survey, she found India needed to tweak it. “The available time use survey or the discussion on time use survey was basically for developed countries …we needed some modifications and a lot of changes in the methodology,” she says. Equipped with a thick instruction manual and intensive training for investigators and a wary pre-testing methodology, Hirway recalls how the first pilot survey was expertly detailed and carefully devised. “We have always been arguing that the TUS is essential for India and somehow [the government] understood this and set up the pilot survey.”

Through the years after the pilot, several conferences were conducted and committees were formed to work towards the mainstreaming of the TUS. Subsequently, it has expanded and grown beyond what it had started out as.

Fast forward to the year 2019, the all-India TUS finally arrived after the government agreed that workforce participation could be tracked better with a survey that carefully maps the respondent’s time. When it was finally conducted under the newly formed committee, Hirway says “there were quite a few mistakes” and “there were entirely new people who had no idea about the time use survey and how it could be utilised, that is the tragedy.”

The Many Holes

Dr. Chakraborty says the TUS has a few critical concerns and a big one is that as the survey period covers only 24 hours, “the widespread presence of the informal sector would be outside the coverage of the time use survey as the work pattern is erratic and irregular.”

As Hirway elaborates in her article, The Time Use Survey as an opportunity lost, the TUS has missed out on the International Labour Organisation’s recent resolution that defines work as “any activity performed by persons of any sex and age to produce goods or services for use by others”. The TUS’s primary objective is to map the time people spent on unpaid and paid work but as both Hirway and Chakraborty write, this objective does not reveal the status of employment of people which is central to the ILO’s resolution. [MOU4]

Furthermore, Hirway writes that the TUS missed the implementation of 5.4 of the Sustainable Development Goal (2030) which is to “recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate.” However, to value the unpaid work, she argues the valuation by satellite account (which tracks things like household assets) is required as it could measure the contribution of unpaid work to GDP and the economy.[MOU5]

Understanding Women and Work

However, Deshpande writes that compared to labour surveys and household surveys, “the TUS is comparatively better. It is up to us whether to count them or not, at least we have the information.” She points out it is a step towards the right direction for understanding women and work. “However, for TUS to contribute to an accurate measurement of women’s economic work, it needs to internalize the framework outlined in the pilot TUS of 1998-99. In the meanwhile, data from TUS 2019, with all the caveats and disclaimers, is a stark reminder of the deep-rooted gender divisions at work and at home.”

On the other hand, Devaki Jain points out the focus which was initially to recognise women’s contribution to the economic domain has now drifted to recognising care work. She argues, “For me, it is first the bringing in of women who are actually labourers, workers of various kinds into the basket of the employed, before getting distracted by including their work in household work.” She points out that women directly contributing to the economy are not yet considered in our current understanding of “work”.[MOU6]

Despite the many criticisms, the pilot and the first national TUS have captured the difficulties of women and brought several changes on ground.

Jain points out how her survey showed that women in the Kaira district in Gujarat had buffaloes in their houses and worked nearly for 18 hours as there was so much work to be done. These were the women who formed Dr Verghese Kurien’s Operation Flood and eventually, the Tribhuvan Foundation set up facilities for them as these exhausting hours affected their health. Jain points out how gathering this data could be central to drafting policy.

She describes how they discovered that women who were nurturing the silkworms in huts in the sericulture areas of Karnataka were hardly sleeping because the silkworms had to be fed all night. She says “…it was a study of time that gave us the insight to look at the assault on the health of women who were part of the sericulture shed.”

Finding out information like this which had never been mapped before could prove to be “a valuable tool to be used in transforming a policy and programme.”

Hirway is back at the drawing board, currently working on a paper on recommendations needed for future surveys. The fight for the implementation of the TUS does not end here. Nor does the fight to make visible the invisible work by women.