This essay was developed as part of The Third Eye’s Sexy Log mentorship initiative, where a cohort of 10 people across India worked independently on their experiences of sexuality, responding to the prompt of Pleasure & Danger.

It began its life as a theatre performance titled Seconds Before Coming. In the present, Rishika Kaushik tells us of the questions — answered and unanswered — that were born at drama school and formed her experience of making the play.

In drama school, we used to spend a lot of time standing around. Now, as soon as I say that, I imagine a chorus of actors yelling at me, saying, “C’mon — we weren’t just ‘standing around’!”

Of course not. I meant, we were arriving into neutral bodies — shedding, lengthening, becoming… the ready actor. I think. It’s hard to fully say. In those potent hours of class, learning at maximum velocity, feeling every sensation intensely, I was always at the edge of drifting. So, after all that standing when they asked us to move on impulse, I felt an oddly familiar sensation: of seeing a stranger and recognising something rising in my body.

There exists a moment when something happens. Behind it lies the moment (the second?) that comes right before. In theatre, this moment in time can be clocked. It is what we call impulse. The urgent desire to act. Ostensibly, impulse jumps right out of you. It makes you do something. Often, impulse is seen as pejorative.

She is so impulsive.

Don’t act impulsively.

Sorry, I was overtaken by an impulse.

“So then? What happens to this urgent desire to act when it is not acted upon? Where does it go?” — I thought, as my class continued to hurtle on. We were doing this drama school module called ‘Improvising and Devising’, where, every day, we worked rigorously to recognise, catch and act on impulse.

The three actions were meant to happen one after the other, in a matter of seconds. It was a game of presence, another word that would haunt me with the ferocity of the past. Another time, we are just standing around. My batchmates walk past me, stop, walk again. Our teacher clicks her fingers in approval, watching one of them take off with intention — “Yes! There it is!”

It's true. It felt compelling, watching her move.

She glances at another student, gasps, “There! There it was, the impulse… you just let it go. Act on it! Move when you feel it.”

“Feel what?” I asked, as I felt myself drift off again.

***

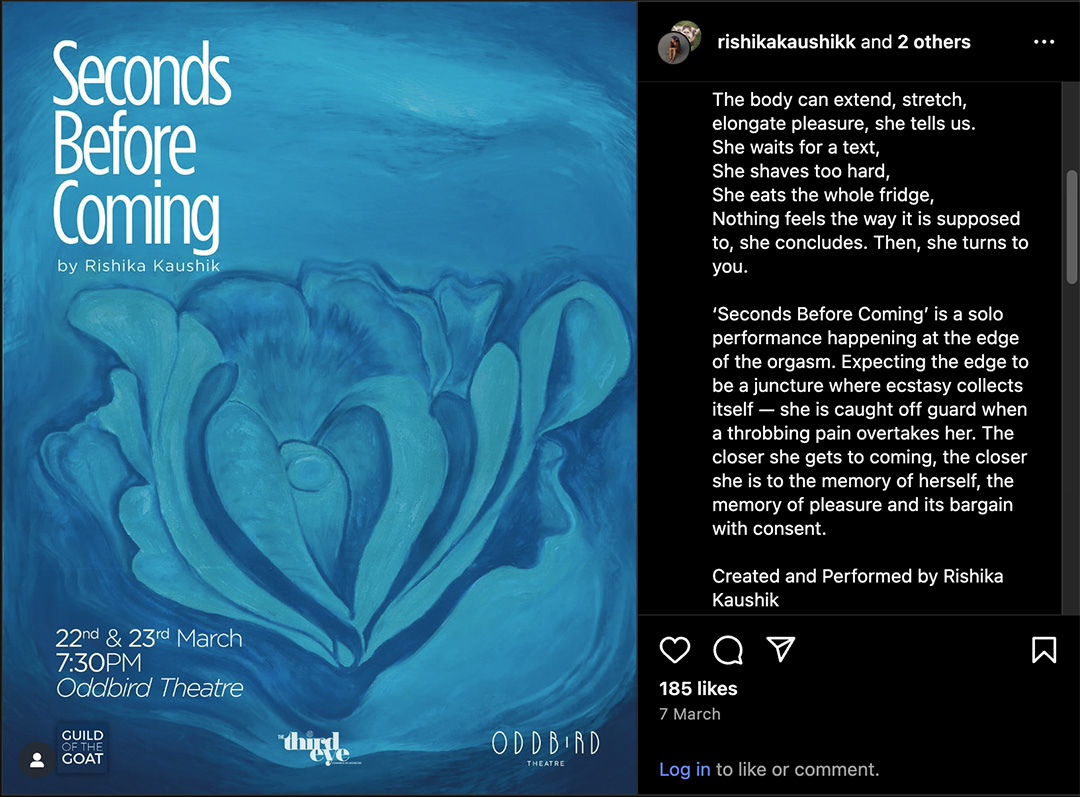

Two years later, on the opening night of my solo performance, staring at the poster —

Seconds Before Coming

by Rishika Kaushik

23 March, 7:30 PM

— I was reminded of the same question I had in class, of suppressed impulses. Where did they go? Looking at the name of the play now, I saw how questions, like impulses, had a way of wrapping themselves around you and staying there for years.

This play, which stretched the second before the orgasm into 75 minutes and asked ‘from where does pleasure arise?’ had perhaps been my body’s way of searching for that moment of impulse.

From where does impulse arise?

Seconds Before Coming is about a girl who falls in love at the age of 11 with a man she calls Bhaiya. The adult is informed by her therapist that children can, in fact, experience pleasure, but that does not mean that they can give consent. In the face of this knowledge, she is overtaken by the past — replaying her encounters with ‘pleasure’: playing chhuppan-chhuppai (hide and seek) with Bhaiya; contemplating the answer to his ‘will you give me a blowjob?’; thinking about the purpose of tits as boys pulled the bra straps of girls seated in front of them; feeling the new slimy liquid between her legs when Bhaiya would touch her, repeating ‘koi aa toh nahi raha na?’ (no one’s coming, right?)

From where does pleasure arise? For some of us, from the thickets of danger.

In the beginning of the playmaking process, this contradictory experience of the body rattled me. To release the heaviness inside, I decided to move. Literally.

Hours of rehearsal were spent just moving — making what I then called ‘senseless dance phrases’ and recording myself. Before long, the movement began roiling, responding to the visceral parts of the self — a sensation, a desire, a memory. Images formed, the body de-formed, distorting itself. I was coming apart on a chair, back bent, legs swimming mid-air, suspended in both presence and memory, gazing at a world upended. From this physical exploration, I dug out the opening image of the play.

It was to open in stretched time and bent space, and it would not close. Instead of the cleanliness of unity, what lay before me was endless contradiction, opposing forces at play simultaneously — all of it a bit of a mess, one that hardly made sense.

This was okay, I told myself. Sense was a thing to feel, not make.

Presence

Here and now, they say. They call that presence (there’s that word again). In theatre, presence is another feeling we are always chasing. It is the thing that makes theatre what it is — alive. The problem is, by virtue of it being here and now, the present state is an ephemeral one.

When I met Anirudh Nair (Rudy, who would go on to become the show’s performance director and dramaturg) at drama school, he seemed to embody presence. He would practice the Philip Zarrilli psychophysical routine with us at the residency, which we called our Morning Ritual. Witnessing him do the practice was like watching stillness in motion. So this is what all that standing around was for, I concluded: to reach a heightened state, where movement and stillness existed together, all at once. In this state of being, the body made time and space palpable, perceptible… maybe even present?

In the years to come, I grew a bit obsessive about this heightened state of the body.

I would propel myself into evermore intense and aggressive warm-ups to achieve it: shaking, moving, stretching, voicing, releasing, until my body vacated itself to a point of total silence, finally open to listening to itself. Being present in the theatrical moment felt like a high: I wanted it all the time, everywhere.

Rudy would find me tussling with this state, years after I first encountered it, while readying myself for the second weekend of shows for Seconds Before Coming. On the morning of our third show, we decided to take a full run-through to familiarise ourselves with the shifts in our light design.

Makers are often divided on this: a run-through right before the show could leave you drained for the show itself. I had decided to get behind this belief, which asserted the dramaturgical importance of preserving yourself. It was a great place to hide the real-life fear I had of my body giving up on me mid-show (a paranoia that will perhaps never leave me). Rudy would call my bluff on this and say — no need to be precious about it, c’mon, let’s go!

Precious. It was a good word to describe my dissatisfaction with the body. After dramatically leaving this precious little dissatisfaction in the green room, I went into the run-through and came back out having given a horrendous performance. It was as if I had departed from my body. Upon finishing the performance, I came back to it, filled with the same kind of shame as waking up from a drunken night with gaps in your memory. I quickly told Rudy to ignore this run —

Before I could finish the sentence, he jumped up to say that it had been my best performance to date, and got busy refiguring the lights plan. I drifted off again, startled by the stranger that was my body.

That evening, when we would discuss this, not too long before the show, I would speak about feeling estranged from the performance, hardly inside myself, barely present. Rudy would think for a while, then say, “We say this a lot in the theatre. But it’s such a loose term. Presence. What does it really mean?”

It’s a unit of time, really: ‘the present moment.’ It’s also a feeling: ‘I felt a presence.’ In one unit of time, I had watched my drama school classmates walk around, acting on impulse. In another, I’d seen Rudy do the Morning Ritual.

There’s something about the way a body invites you into a certain moment that makes it — the moment or the feeling — visible. Making the hidden visible forces one to see, when you would rather look away.

Was presence the impossible act of not being able to look away?

To add to these confusions, my feelings about being present were entangled with my unrelenting fixation on the past. In the early months of rehearsal, I had scribbled in my notes: the shadow of the body is memory. It felt to me that most things became visible only in memory, in the shadow of the present moment. I was going in circles, being jostled by these seeming oppositions. And then, while circling, something else started becoming visible to me.

Crying Through Comedy

It was this: feelings, perhaps, are circles. Push the limits of one feeling and you will come face-to-face with the opposite feeling.

Of course, I didn’t know this when I began writing a comedy. I did it because I believed comedy unlocked hearts, warmed them, sometimes even burned them, but (in keeping with the theme of things) pleasurably, like a shot of tequila.

The best part about writing comedy is that it is wildly fun. Often, I’d write bits imagining only my little team as the audience. At the time, the team consisted of two sound designers (Rish & Surbhi) and one creative producer (Meghna). Writing for the world is scary; writing for three people you love hanging out with is basically prepping for a party. We’d stuff ourselves in Rish’s little home studio and I’d get right into it, performing the newly written bits for them. The moments I’d receive their laughter would fill me with an inexplicable joy. We’d jam with the new material, cackling the whole time. Eating samosas and spring rolls after, we’d chat endlessly about everything, from the present to the past.

A play is its people, and these ones grew to be my dear friends. Within this, developed the protagonist’s relationship to her audience. I imagined the spectator as always there, sometimes invited in, sometimes inescapable. At points, the protagonist was uncomfortable — she’d rather not be seen — and in other moments, they’d much rather not have to see. Moving together, the performer and the spectator arrive at a strange intimacy, at once thrilling and humiliating, vulnerable and fortified, almost at the edge of a romance that eventually unfolds itself into the warmth of a soft, abiding friendship.

Comics often say that comedy disarms because it says to your feelings, ‘It’s okay.

You are safe here. You can be easy.’ But I think comedy does more than just that. It creates room in the body. It turns, spins, flips. Like feelings, it cycles into its opposite. In the act of laughing, you can gasp for breath — you can laugh and laugh and laugh, till you cry. At the edge of comedy is catharsis. At the edge of catharsis is endless space — the vacant, present body that can finally listen to itself.

(In)visible

To listen to your body is a radical act. It means listening to its silences, oppression, grief, rage, power. After the play, my friend hugged me and said she found it hilarious. Another woman found she couldn’t laugh at all. A woman I knew only from a distance but admired deeply, hugged and thanked me. Then I thanked her, and we both laughed awkwardly while crying. Someone said that they wanted to laugh, but had stopped themselves. A friend I’ve known for years said, “How dare you do this to me?”

Standing around people old and new, the circle became visible to me again, literally and figuratively.

In another one of our classes at drama school, we run about, trying to perfect the act of coming together in a circle. “Five… four… three…” our teacher counts down, sending us scrambling, pushing against each other, elbowing for space. We gesture at one another to go back, come forward and finally, nod in dissatisfaction at the egg shapes we have created. Our teacher eventually tires of it and tells us that the point of it — to make ourselves a perfect circle — was to make sure everyone was visible to each other.

“Presence. What does it really mean?” That’s what Rudy had asked me when I’d told him I had disappeared from my body, but what he had seen was that I had become starkly visible. Perhaps it means receding from the dissatisfaction of the body, and dissolving into the circle in which we are, for a brief while, visible to each other.

-

Rishika Kaushik is a theatre-maker, writer and teacher based in New Delhi. Her arts practice emerges from the body, and is rooted in impulse, memory and sensation. Driven by experimentation in her dramatic writing, she likes to play between uproarious laughter and irrepressible silence. Her plays include Love is a Potato/Salad and Seconds Before Coming.