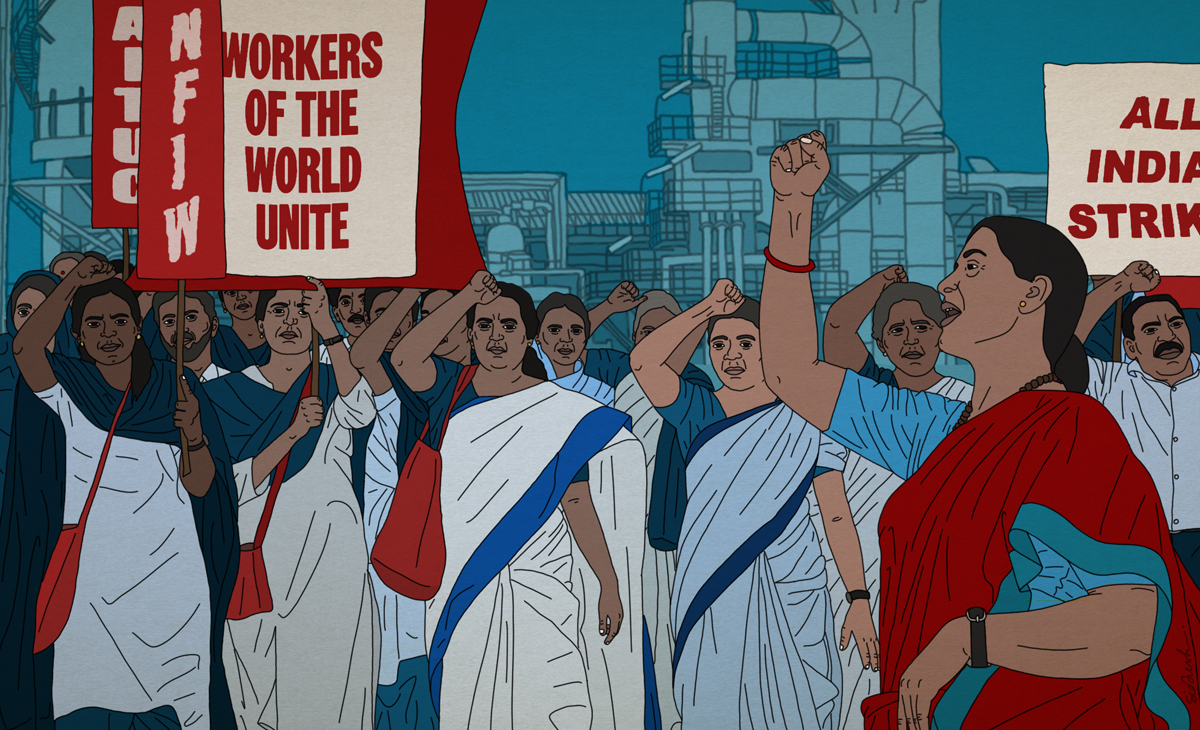

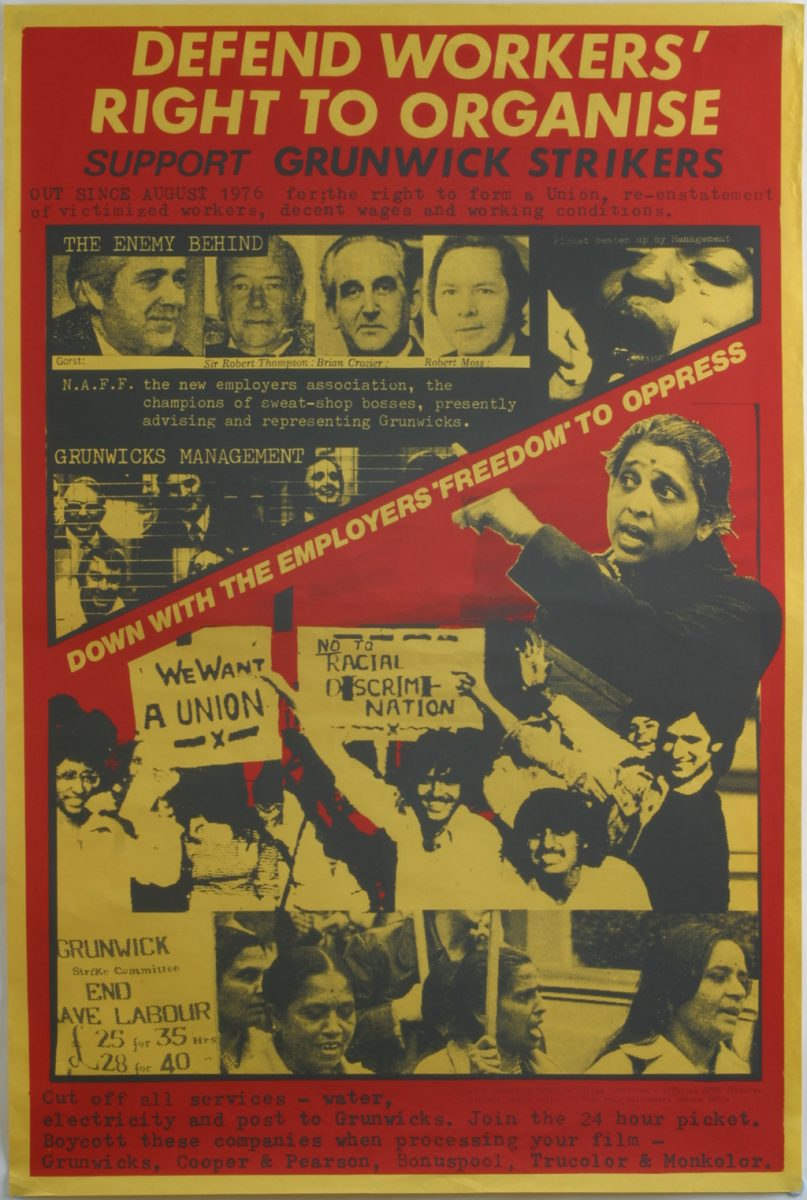

Annie Raja is the General Secretary of the National Federation of Indian Women. In over 65 years of its existence, the NFIW has rallied behind issues that affect women’s rights as workers, as well as their full citizenship in this country. Health and safety, state benefits, education and housing, and infrastructures of justice have all fallen under the purview of work done by them. This work constitutes primarily of building solidarities, network formation among collectives, knowledge production, data gathering and dissemination for the purposes of political and civic engagement, and lobbying for progressive, feminist change. The NFIW is the largest women-centric pressure group in the country, and its reach through metropolitan and through remote regions is unparalleled.

Annie Raja’s lifetime association with the NFIW has seen her help organise and unionise women’s work across class, caste, religious, and sectoral divisions. Through this interview, she sheds light on the process by which a collective (of women, workers) might form a union, and the challenges they face in attempting to secure their rights in neoliberal India.

How do we in India frame the right to livelihood? Are there any constitutional or legal provisions for workers demanding this right?

No. A neoliberal economic policy is in place in our country. [Its] core formula is competition and privatisation. The overriding precept of neoliberal economic policy is ‘ease of doing business’. What that really means is a prioritisation of employer over employee. Which means we dilute all labour legislation.

First, the employee does not get the status of a worker because ‘workers’ are entitled to a minimum wage and other provisions in accordance with labour laws. Second, the government gives private employers an ‘out’ from their responsibilities simply by changing the relevant definitions. For example, a workplace is no longer legally a workplace unless you engage 20 workers. And it is only in a workplace that you are supposed to provide. So, when you have fewer than 20 workers in a space, you are saving your money by not giving minimum wage and other entitlements.

Third, you give all these benefits to corporates to come and set up operations in this country, in this state – you give them cheap land, water, electricity, resources. You take away common goods, public goods, public resources, or in other cases, take away resources belonging to individuals and give them to corporates to set up another company… ‘Ease of doing business’.

But the core character of neoliberalism is exclusion. No matter how much anyone talks about inclusive growth – what we have is the opposite of that. Privatisation, the government stepping away from what should be and were social sectors; whether it is health, or education. It’s what happened over the past 20-25 years – private players were handed the keys to children’s education and people’s health; they decide how to operate, they decide what the priorities are, and whom to let in. They are free to decide terms of work… More and more workers are pushed into the unorganised sector. Thousands and thousands of workers have lost their rights as workers, and with it, the safety of the organised sector. The confidence of the worker is gone. 96% of women work in the unorganised sector! If you are trying to address the life and livelihood of this 96%, it is not easy.

So, what effect does unionising have then?

The government does take note. If I go out and shout slogans for the domestic workers, no one takes note, but if ten groups come together, and a hundred people’s voices join, that voice is louder. 60-70% of the Indian Parliament are [comprised of] business people. They have their own industries. Can you imagine, or can you expect, that they will talk about the domestic worker? They will talk about the agricultural worker? No. They will be interested in how policy can be changed to benefit their own profit interest.

Among them, though, we must try and find the people with compassion, and try to lobby with them. We need to give them information, sometimes, about what all has been going on… We need to involve the political will of people in power.

Let me give you an example. You know the form in which NREGA was passed by the government in 2005. Since we’ve been working with women from all segments of society for so long, we knew the ways in which it wouldn’t work. So we lobbied with the government to make changes and additions, and the government took our input into account. They verified what we were saying, and made those changes.

That is participatory governance. For it to flourish, you need a government to understand and respect that process of citizen participation. We have to ask, does the government make laws to benefit the country’s labour force or do they dismantle existing laws? Do they listen to citizens, to civil society, to development sector workers, or do they persecute them?

What is the role of the union in the neoliberal world? How does it need to adapt?

First, unions are still all about the organised sector. They have already had to go through a lot of thinking, a lot of changes, because the neoliberal system has thrown up such a vast unorganised sector and contractual workers.

Then, trade unions have to attend to issues faced by other sectors. So the Anganwadi union must speak to issues faced by ASHA workers or the mid-day meal worker.

Another thing is to realise how many places unions are not even allowed. In the new sectors, in special economic zones, unionisation is prohibited, which was never the case before, never possible before. And you cannot hoist a union flag in front of your building if you are in the IT sector.

And even if it is allowed, even if people are able to question and exert pressure, you have to remember that government – and I’m not naming political parties –

any government operating within and in accordance with neoliberal ideology - is with the company. Not with the workers.

So even if young people protest and insist on forming a union, legislation changes so there are hundreds of conditions imposed on the union – hundreds of requirements they have to fulfil and operational directives to abide by – to keep the union going.

So there is always the threat that the union can be shut down for non-compliance – it could be any reason. So there cannot be a functional union, freely demanding better working conditions and better wages for employees.

For the trade unions, to keep going, getting stronger and stronger, they need people. They have to carry the interests of other sectors, and unorganised sector workers.

Another challenge is that they need to be able to deliver. If you can’t show that this is what we can do for you, then no one will participate. Because life is so difficult, everyone needs to gain something. So, they have to show the worker, look, it is because of us your hundred rupees have increased. And that needs sectoral struggles. So, trade unions have to engage in sectoral struggles, but on multiple fronts.

Any particular women’s unions in recent history that you consider ‘success stories’? Who managed to draw the attention of the relevant people?

Bringing domestic work under the umbrella of ‘work’ that ‘counts’ in calculations of the GDP and in the Census is a success. And we played a big role in that. Right now, take the case of Anganwadi workers. Many local collectives organised campaigns based on their Joint Charter of Demands. Individually, they keep the Joint Charter alive through periodic dharnas and rallies. Their wages were recently increased by the central government. But again, this instance also emphasises that at this particular cultural moment it would be very difficult to fight alone and gain something. Our times demand a joint effort.

In your view, why are women underrepresented in the Census?

Because think of it:

the domestic worker indirectly helps facilitate every production process in this country. If I come to your home and do the housework, then only you have time to go to your office and generate revenues. And your work facilitates ten other employees’ work, and ultimately everything is part of the national income. So, I earn and generate income, plus I indirectly increase national production, via the people whose time I free up. I am giving labour and time, why should it not be counted?

The tragedy is that our work is not counted in monetary terms. That is why the work women do is not counted during the process of national income accounting…Unless my work is recognised as ‘work’, how can I get benefits?

In Kerala’s Wayanad district, the women decided that they would not cook one day. Think of it, all men have to go to the hotel and spend money. I don’t know why men say, “Main paisa leke aa raha hoon, tu aisa kharcha kar rahi hai” (I bring home money and you spend it all). From morning onwards, I save double of what he brings home! So, I am helping with my labour and my time, I am a crucial part of the economy, of the national income. That is the NFIW’s argument.

What are some of the instances of resistance you’ve seen, among and by newly formed unions?

For one thing, it’s resistance from existing unions! However progressive they purport to be, they won’t want another union to come up in the same place of work; all the unions will come together to oppose it. If we’re speaking of the unorganised sector, it’s a vast ocean. I don’t think even 1% of the unorganised sector is unionising. It’s a huge challenge.

Since last year, we’ve been working with home-based women workers, and we held a public hearing in Delhi. There were a few economists, research scholars – and our target was that 70 workers should come. They set down 100 chairs and I said remove 30. Women started coming. Ten more chairs, 10 more chairs. Finally the auditorium was full and people were sitting on the floor. The sort of testimonies. We did not pre-plan anything, we didn’t say come prepared to speak. We only said generally, aapko aakar apne baat bataana hai (just tell your story). 138 women. One of them said she works six hours, after all her housework, at night. And she gets three rupees a day. That tells us the crisis of her life. The people on the panel were shocked.

But to hear those stories – not just us, or the panellists – these women were meeting each other for the first time, hearing each other’s stories.

So, my advice to anyone working in this field, or just starting to work with these women, these workers, is to organise them. Unionisation is a later thing. First, help these women gain confidence, in themselves and then in you.

Because they need to believe you are there to help them, not just listen and go away. And they’re giving their time – they’re coming to the meeting for the first time – and in that time they could be doing something – work they desperately need. They’re leaving that and coming to you. So, in the first meeting, you may get only 10 participants.The others may say why should we waste our time -– usme paanch rupaye ka aur kar lete hain (I’ll earn another five rupees in that time). But it is for you to command the confidence of those who come, so these 10 people will go back and say to others, speak to these women. And you too should have the right attitude – not as though you are their leader but an instrument for them. Naturally, the leaders will be from among these women. Your role is at the back.

Once they feel confident they can depend on what you say, they themselves will bring more women. You do not need to go door to door and enrol prospective members. Once you think that we have 1000 people, or even 500 people, take their consent – kya hum union ki taraf badhen abhi? (Shall we move toward unionisation? Ladai ko aage badhaen, taki sarkar bhi humein sune, adhikari bhi humein sunen. Take the fight forward, so government, officials, police and the rest sit up and listen. To unse hi consent leke kaam karna hai (The consent and participation of union members in this process is indispensable). Yadi membership kar rahe hain to unse hi pooch ke rakhiye ki 2 rupaya rakhe ya 5 rupaya rakhe, mahine ka rakhe ya salaana rakhe, kab milen (Ask them how much the membership fee should be, a monthly or a yearly contribution, monthly or weekly meetings…) They should be part of the decision, and over six months or so you build a good rapport with these women. Whatever you are doing, is helping them toward collectivisation.

What challenges will they face in registering their union?

Labour offices are absolutely anti-labour. They are not labour-friendly. It is for anyone who is trying to organise them or unionise them to go and speak to the labour offices. And sometimes take the help of the larger unions. That is what we did. Now, we are trying to unionise home-based workers. Ye samudra ke jaisa hai, koi puhunchana hi hai unke paas. (It’s like a sea. No one has even begun the real process of working with them on collectivisation.)

For field workers working with women in the informal economy, what advice would you give?

Be part of the larger discourse. Bring change into the system of resistance itself. Sometimes you will force them to think, but usually trade unions are happy to incorporate your demands alongside theirs in some way. You incorporate your demands into their demands. And the larger discourse begins to reflect more in yours as well.

There are many sections of women at present that trade unions have not reached… But if a national trade union is organising something with Anganwadi workers in Rajasthan, and Delhi Anganwadi workers have not collectivised or affiliated themselves with the trade union, they will still benefit from that alliance in some way. Similarly, if there is a protest action in Delhi, a large number of workers on the ground everywhere else too will benefit.

But most importantly, being a member of the union is fundamentally empowering. The association is not always just a question of monetary or legislative benefit. There are a lot of dimensions. Dosti itself is a… solidarity. The feeling of having somebody, even the feeling of friendship gives us strength. And we always need more strength.