Nangsel Sherpa has participated in the Travel Log programme with The Third Eye for its City Edition. The Travel Log mentored 13 writers and image-makers from across India’s bylanes, who reimagine the idea of the city through a feminist lens.

Nangsel writes from Darjeeling, West Bengal.

This piece is the first of two columns from Nangsel’s life and observations in Darjeeling.

My neighbours had started dusting their carpets on their balcony. My mother hurriedly closed the windows and asked Maya-didi to do the same. Maya-didi had started fuming, “Yo Kami haru tah kosto cha hau, byan byan nai shuru.” (Why are these Kami people this way? They have started early in the morning.)

The facade of harmony also breaks early in the morning in our tiny hill town of Darjeeling.

It was Friday and I did not like that such statements had become a part of our daily morning routine. It was useless for an eight-year-old to say anything but Maya-didi was referring to my friend’s family.

Storerooms and my Feminist Utopia

I was looking forward to the evening. Fridays were extra special as they marked the end of our school week and also the time when all my friends met me at 3 pm in the storeroom on our ground floor. Adults like my mother or the neighbour uncle who used to dust his carpets would never be able to imagine what we were up to. Nor could they step inside the world we created for an hour every day.

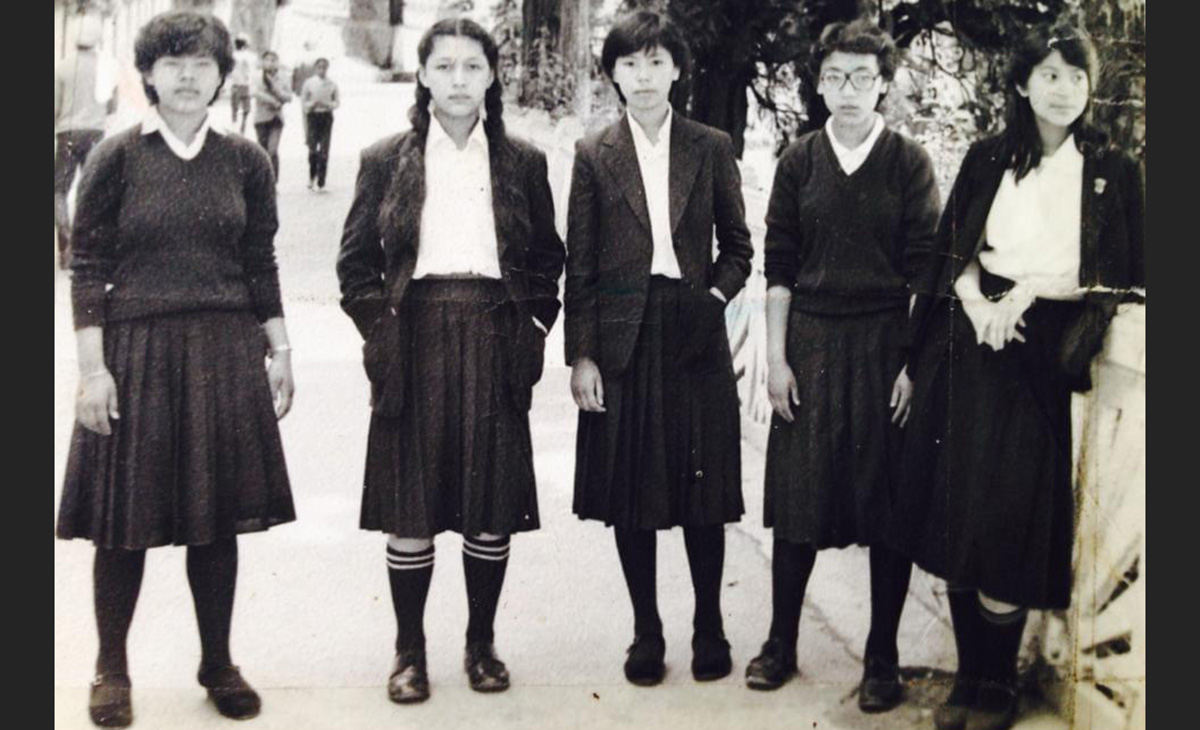

By evening, I was walking fast and I could feel my tiny ponytail swinging left and right as I rushed home, looking forward to meeting up with my ‘gang’. I had been friends with each girl and later introduced them to one another. The gang’s name kept changing. It was Famous Five. Then it was Winx Club for a while. We watched Winx Club diligently, looking at those fairies take on the world and challenge Evil. At home, after drinking my mandatory milk tea and puff biscuits from Walis Bakery, I stepped inside the choesham (prayer room). Popola was busy with his prayer beads chanting, “Om Mane Padme Hum.” As usual, I shouted, “Popola, nga tsemo tsega dogi lo,” (Grandfather, I am going to play outside) before rushing out of the gate. Niloufer, already near the storeroom, asked if I had brought the keys. I had stealthily taken them, tucking them neatly in the pocket of my navy blue jacket, securing it to prevent their falling if I ran.

Niloufer was a Tibetan Muslim and her grandparents adored me, so it was easier when she asked permission to play at my house. She was the batthi (over-smart) one amongst us and we were in awe of her cursive writing.

The next stop was at Geetanjali’s and then Khushbu’s, whose family were tenants in Geetanjali’s building. I was extremely fond of the aam ko achar (mango pickle) Khushbu brought back after celebrating Chhath Puja in her village in Bihar. The other two were scared of Geetanjali’s thulo-ama (grandmother) and thulo-baba (grandfather), which left me to ask permission for Geetanjali to play at my house. They usually obliged but some days she was not allowed to play, to our disappointment. It was her father who had been dusting the carpets in the morning and I could see them hanging in a row on the balcony railings. The four of us headed down the streets to Pooja’s house and asked permission from her mother. Pooja was a Garhwali from Dehradun whose family had recently relocated to Darjeeling after her father’s transfer to the Central School for Tibetans (CST). We became friends when the shopkeeper below her house introduced me to her, asking me to show her around and introduce her to people her age. Today, her mother gave us a contented smile as Pooja left with the rest of us.

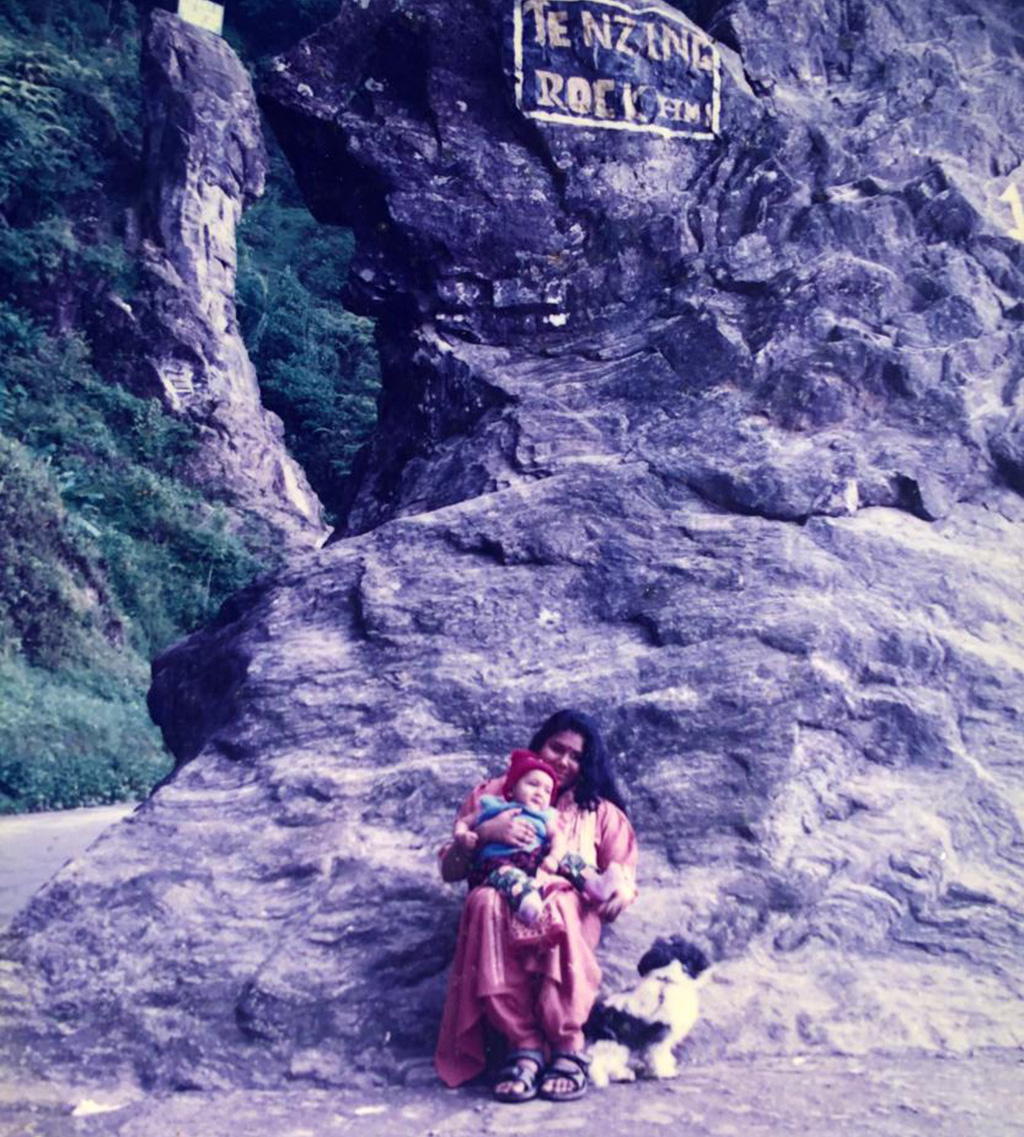

After going up and down Tenzing Norgay Road, I finally opened the storeroom.

It had a few gas cylinders that my family had stored, and old and unused things each one of us had brought from our homes.

Geetanjali had brought a small wooden temple that was old and unused. It was the main attraction in the room. It had no idols but was symbolic for us. Pooja and Niloufer had brought carpets and sheets from their homes, which became our beds and sofas during play. Khushbu had brought an old kerosene pump stove that was kept at the right side of the room, away from the temple but near the gas cylinders. She had also brought a kadai [wok] to help us cook our mini dishes. While everyone was busy cleaning and arranging the room, I brought some toys, cushions and bedsheets to transform the store into something magical, which the adult world would never see nor be able to appreciate. For the five of us, it was our home, away from schoolwork, our parents, the constant pressure to excel at school, or the fear of being the ‘other’ and bullied.

We were different from each other but similar in how we all were with each other.

Today, Khushbu was supposed to help light the stove with the kerosene pump and we all gave her a hand. It was old so it took us some time to push the pump. One person alone could not do it and all five of us had to try our level best with our nimble fingers to ignite it. Khushbu, being the eldest among us, had some idea of the task in front of us. As the elder sister to two brothers, she was often in the kitchen helping her mother with the cooking and groceries.

Finally, the stove got going and the flame flickered. The euphoria we felt was overwhelming. Geetanjali had slyly smuggled in more utensils and we were using, for actual cooking, some of the toy spatulas we had bought to play with. I remember looking at those spatulas while going with my mother to Chowk Bazar. Beech Galli was usually not a place in children’s fantasies but for me it was. The Galli is a maze; I was amazed at how swiftly my mother located the shops. I usually clung to her, not leaving her side even to eye the numerous toys and playhouses decorated outside those shops, a clever lure. I was scared that if I were lost in this maze, which only the adults seem to navigate, I would not be able to find my way home.

Half-boiled Potatoes and Beef Curry

It was only last Sunday that I had gone to Beech Galli with my mother to buy gundruk (dried and fermented green leafy vegetables) and I had yearned for one of those whole kitchen sets. But my mother refused to indulge in any of my tantrums that day, and I had to keep the pretence of being the good child. I stopped asking after her firm “no”. And now, Geetanjali had brought that very kitchen set to help us with the cooking, and some old steel utensils lying in her kitchen, which she had sneaked inside her bag of toys.

The entrance to Beech Galli is filled with shops that sell local aloo chips, bhuja and other fried goodies. There are several lanes, connected but distinct. Each lane is dedicated to specific things – toys and makeup; vegetables; the local Darjeeling tea; sweets; sweaters; spices, local condiments and dried fish. There are lanes lined with wholesale shops, in front of which aunties would sell dalle (local red chilli), churpi (local cottage cheese), tamba (bamboo shoot), mushroom, paneer and local fresh, green, leafy vegetables. There was also a lane bustling with steaming soups, momos and taipos (stuffed steamed buns) from the kitchens of tiny restaurants. It would be impossible to not visit Beech Galli and miss the strong pungent smell of the sitra (dried fish) neatly arranged in small sacks in front of the shops.

Pooja had brought some rice in a plastic bag and potatoes, so we hoped to boil the potatoes and make aloo dum first, and boil the rice. The five of us squatted around the stove and started boiling the rice. The aloo dum recipe required oil, salt and red chilli powder.

Aloo dum was our favourite ‘outside food’. The town had several aloo dum shops but the only time we were allowed to eat it was when we visited the Dara, the old observatory hill behind the Chowrastha, which hosted all gods and goddesses. It was a ritual to sit inside the resting hall, drink tea and eat the aloo dum, which tasted so different from those made at our homes and was the best.

The aloo dum we made turned out nothing as we had imagined, but we began eating those half-cooked potatoes because it was the result of our labour.

Geetanjali said she was hungry. We all were, after our high hopes on those potatoes. I went upstairs and looked around in our kitchen. Maya-didi had cooked some beef curry for lunch and I filled the leftovers to the brim and took them downstairs, dodging Maya-didi’s eyes.

We all squatted to partake of the dish. Niloufer’s aunt used to make the best beef curry in the whole world using star anise. Geetanjali, Pooja and Khushbu had never eaten it. Khushbu was a bit apprehensive but when she looked at how we devoured the curry she couldn’t resist any longer. Geetanjali exclaimed, “It tastes like chicken to me. Why don’t they cook it in my home?” I didn’t know what to say. I had vaguely heard someone mention beef that had to do with their religion. But for five young girls who were famished, adult codes and rules were shed as we entered the storeroom. For us, the golden beef curry was nothing less than the imaginary pot of gold.

Chowrastha – Our Playground

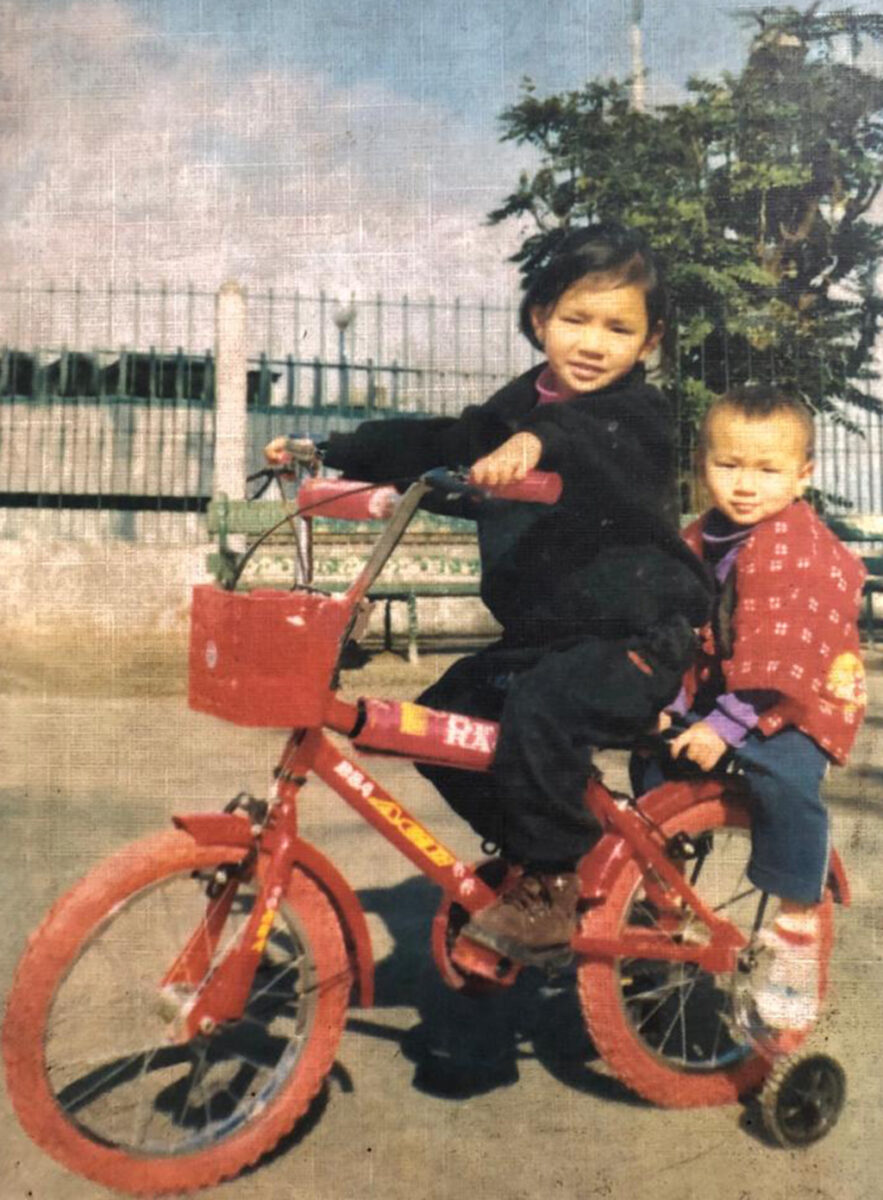

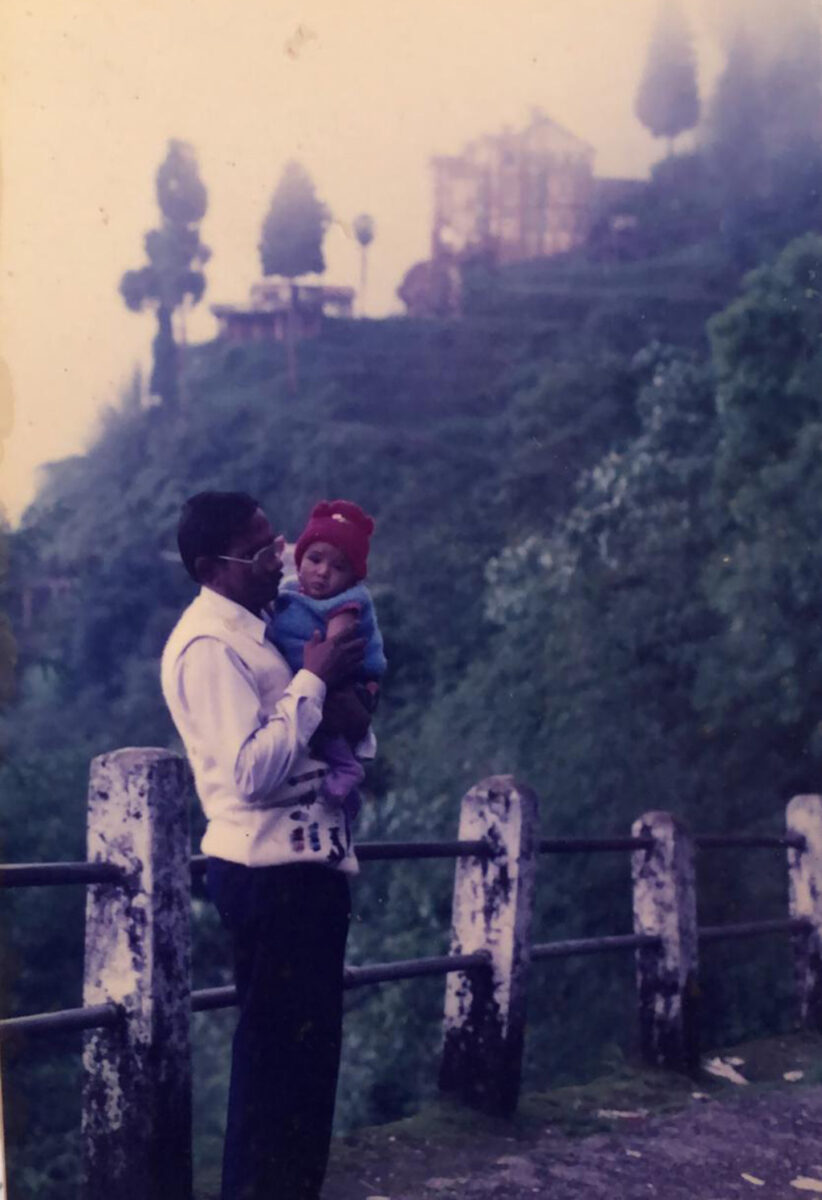

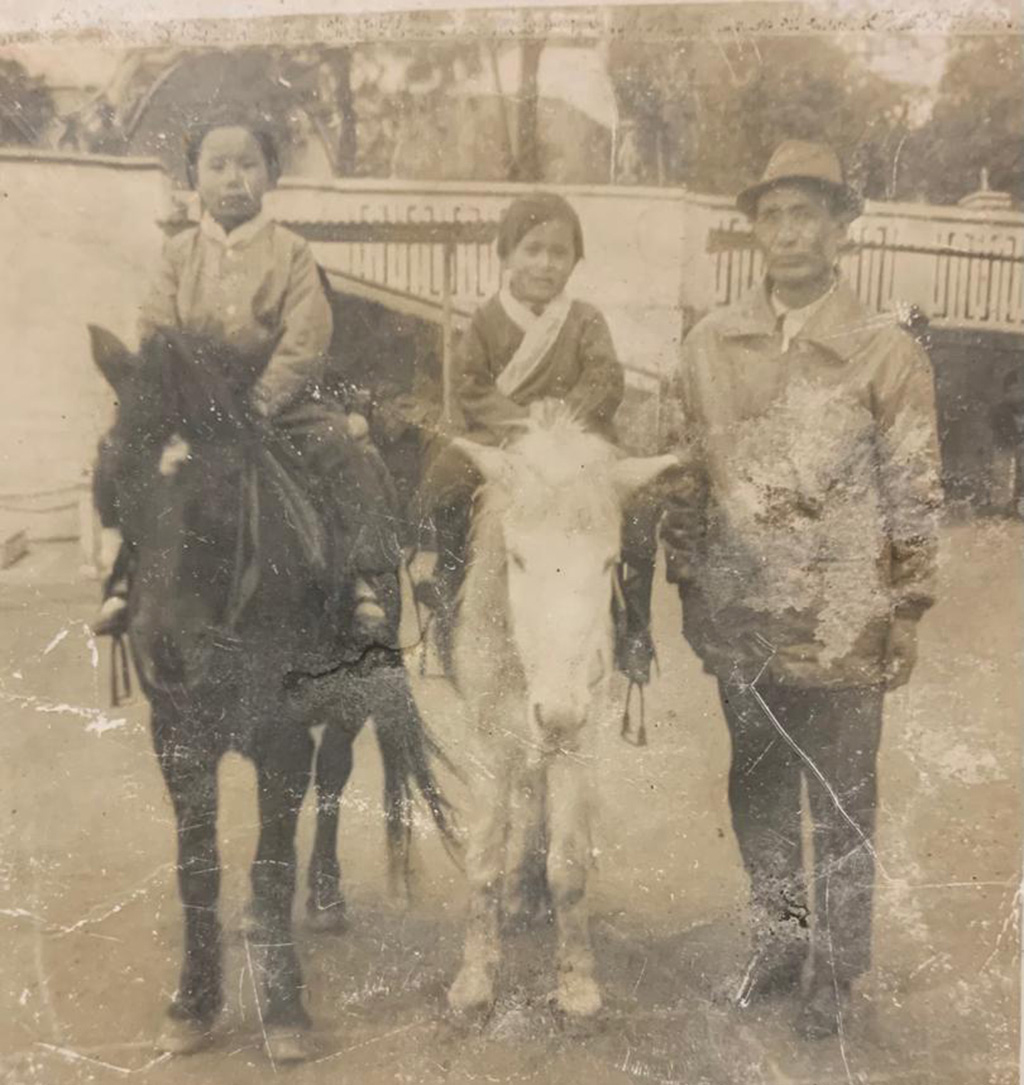

It was almost the end of November, which meant the season of oranges and lapche kaulo (local avocados). The five of us would often cycle in the Chowrastha late afternoon, basking in the sun and looking at the manes of the wonderful ponies. We had to cross the stables before reaching the Chowrastha, and we used our handkerchiefs to mask the stench from those stables. It was almost an unspoken rule for most of the townspeople to photograph themselves astride a horse on their birthdays or on special occasions. The moments frozen in those photographs remind me of our childhood. I have seen images of my parents as kids on ponies and, have posed similarly on my own birthdays.

My friends and I would take a quick ride on our cycles around the Mall Road exclaiming how beautiful the mighty Kanchenjunga looks, and practise our primitive gymnastic skills on the metal bars by the pavement. Grandparents and couples sitting on those green benches, everyone in their own reverie; some lost in fatuous love and others escaping the travails of life.

That day, as the sun set, we raced each other till the end of the Mall Road, where we saw someone selling green oranges cut into halves, laced with red chilli powder and salt. How could the five of us ignore this divinely sour joy? We searched deep inside our pockets and counted the coins. We only had enough for two slices, which meant we had to share it. Niloufer quickly went and bought the slices. We sat on the steps near her shop and ate the green oranges, watching horses trotting past with small children on their backs.

Pooja said, “Look at those horses being dragged about with children on their backs.” Khushbu said, “Hamro ama baba haru pani tyo ghoda jasatai nai ho ni?” (Aren’t our parents like those horses?)

We were utterly confused by what she meant, and she indulged our confusion. “Aren’t our parents living the same life that is expected of them? Being pulled around by duties towards our families, carrying the burden in the same way that the horse is carrying the child…”

Pooja suddenly reminded us that it was late and Niloufer remembered she had to rush home for her evening prayers.

The adult codes we had forgotten in that storeroom reinforced themselves as we passed the teen bato (the point where three roads meet) near our locality. Each step we took, we began to worry. I was worried my grandfather would scold me for being late. Niloufer was worried she would miss her prayers. Pooja looked dismal as she remembered she needed to get her class test papers signed. Khushbu was thinking of how her younger brothers were at home and how she had to help her mother in the kitchen. Geetanjali looked petrified: she had forgotten to drink her milk that day and prayed that her father would not unleash his anger on her yet another night.

As we bade each other goodbye stepping over the threshold of our homes, despite our worries, we promised ourselves to meet in the storeroom the next day and reminded ourselves to save our pocket money to buy those oranges next week.