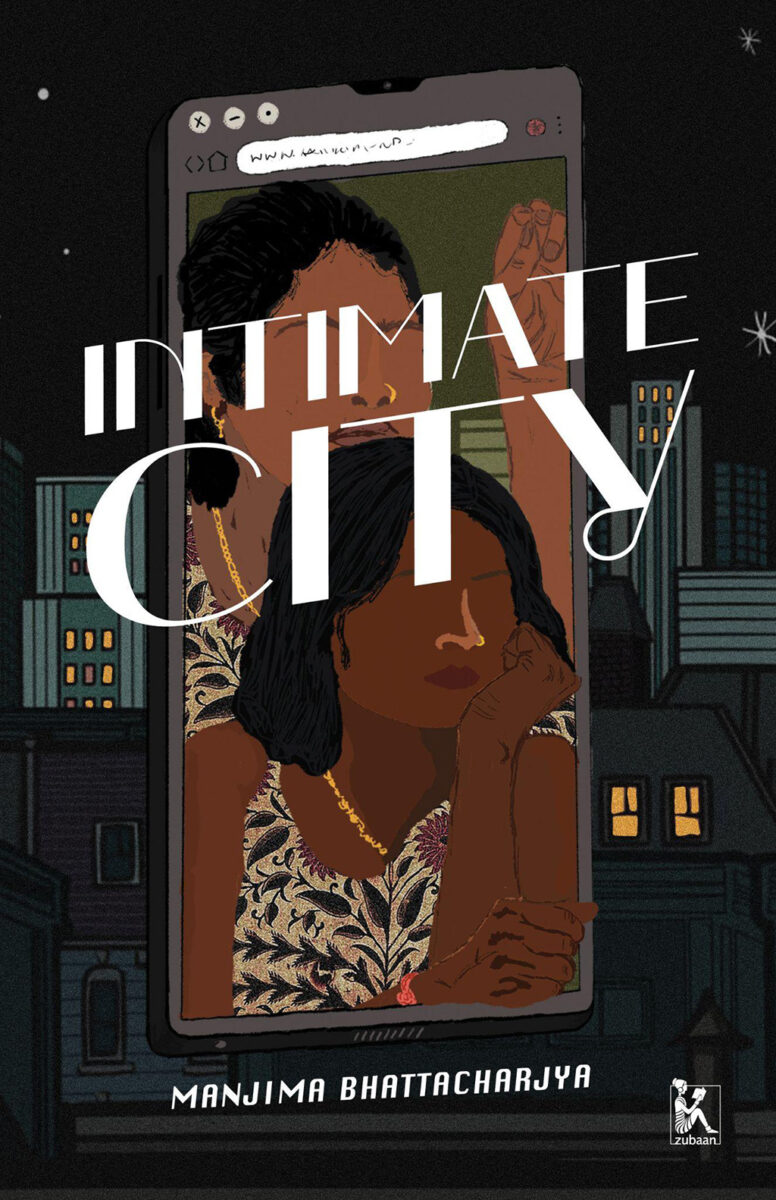

Manjima Bhattacharjya is a feminist researcher, writer and activist. She has been part of the Indian women’s movement for over two decades. She has researched women sarpanches, women in the fashion industry, and the relationship between sexuality and the Internet, among other new frontiers. In her 2021 book, Intimate City, Bhattacharjya examines how globalisation and technology have changed sexual commerce. She offers intriguing insights in how the Internet was changing digital intimacy, a short minute before the advent of Tinder and similar apps. And all this against the backdrop of Mumbai, the city that has shaped the popular (and often the academic understanding) of work, feminism, sex work and urban living.

We wanted to start by asking you about this sentence in the beginning of your book Intimate City. You write, “World cities are often sites of seduction metaphorically and literally.”

Manjima: When I wrote Mannequin—on women in the modelling industry—one of the threads in there was how the pull of the city tempts young women to overcome many hurdles and negotiate their way to the city. They feel the city is going to help them break out of the cages they feel they are stuck in. That they will get freedom and mobility in the city.

While we think of cities infrastructure—flyovers, malls, highways, airports and things like that—actually, it’s a crucible of people’s desires and emotions.

There’s something emotional about the pull of the city and that’s what I was trying to point out. The world city embodies many desires and it offers a place where people think their minds will be blown and they will get plugged into a new current. That was the starting point.

Anveshi has a really interesting report (on women migrating to Hyderabad) called ‘Metropolis as Patriarch’. I loved that title. Women realise that the city is also the patriarch as they find out that in hostels you have to come back at a certain time; in workplaces, you have to be a certain way. The city is trying to surveil and manage women in the same way as many other institutions. But still there are cracks and possibilities. That’s the framework I wanted to enter through and sexual desire is part of that.

Early in the book you note that there’ve been many changes in the two decades of your engagement with researching sex work. Would it be possible for you to give us an overview of these changes?

Till a certain point in India, the ’60s and ’70s, the debates followed the global trajectory. And global positions among feminists were divided. It was called the ‘Sex Wars’, ‘The Feminist Sex Wars’. One side believed prostitution is sexual slavery; its existence is an expression of male domination and that women cannot ever really consent to such sexual slavery. They believed that abolishing prostitution would mean that male domination has been abolished. That’s the root ideology for an abolitionist position of feminists towards sex work.

The other side believed there are circumstances in which women can choose to consent to sex work and this is the lobby that eventually called it ‘sex work’. They believed that prostitution constitutes sexual labour and women have the ability to think about it and to consent to it. So, these were the two big positions.

This is the same sort of trajectory that Indian feminists had too. But there are other complications. We also have our history of the Gandhian feminists in whose moral framework sexuality is not deemed a comfortable subject to really talk much about; so abstinence is given a higher value. We also had the experience of colonisation, which meant that there were these laws that were created around trafficking and clear-cut boundaries between sex workers who had come from abroad. In Kamathipura, for instance, there was the Safed Gali in which women who had migrated from abroad were set up and then the rest of the area was occupied by Indian women who were to service the soldiers of Indian origin. These other histories contribute to certain positions about sex work.

In more recent times, those two positions became more complicated because of the sex workers’ rights movement. When HIV awareness-raising happened, sex workers began to be organised into groups so that they could be given condoms and so they’d be able to negotiate with clients to use condoms and so on. That led to the creation of the sex workers’ rights movement and this conceptual shift…

There was no history of unionisation before that?

Yes, unionisation was an unexpected consequence of the anti-HIV work. It was intended to intervene with sex workers who were seen as vectors of disease. But then it led to another level of self-awareness.

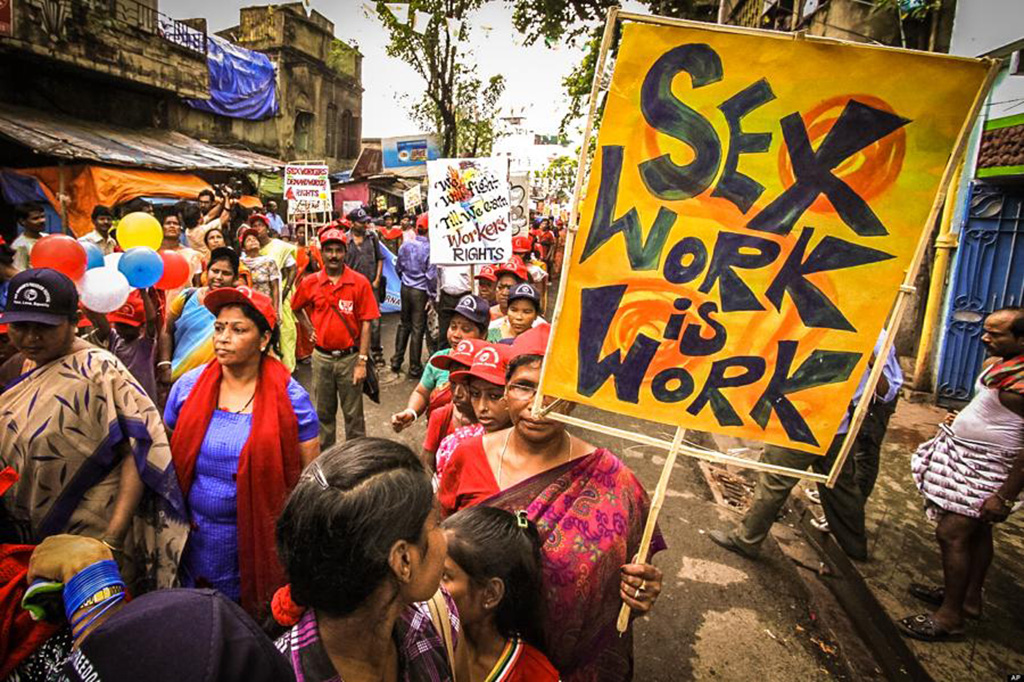

The labour history of India crept into that, the pride of doing work, being independent … I remember when the first national sex workers’ conference was held in Salt Lake Stadium in Kolkata in 1997. The Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee had mobilised thousands of sex workers. At the conference, they said, “This is work. What we do is work.” They had a feminist manifesto which was crafted fantastically with very deep ideas about empowerment and agency. This was a new feminist voice and very significant. This helped many feminists who were ambivalent [about] thinking [of] sexual labour as sex work.

Then, another turn came when the feminist movement developed sharper thinking around identities.

Dalit feminists asked, “Who are the sex workers in India? They are primarily Dalit women. So, their choice is not really a choice. It is to do with caste-based labour.”

Only within the context of their lives can we understand and make sense of their decisions.

But, alongside this, the abolitionist lobby continues to exist. That has been strengthened by the trafficking discourse that conflates trafficking and sex work so all sex work is considered to be trafficking and all women sex workers need to be rescued. These sa viour kind of organisations…

The Raid and Rescue model, right?

Exactly, raid and rescue and rehabilitate. But even in this lobby there are nuances that need to be explored more. For instance, there are anti-trafficking groups who work only with the children of sex workers and they are not trying to rehabilitate sex workers themselves. The focus is on expanding opportunities of sex workers, rather than changing the work of women in sex work. It is not so black-and-white: which organisations are anti-trafficking but not saying dandha band karo.

This has been really helpful. There are other factors that you focus on in this book, such as technology and globalisation. You say that globalisation changed sex work to what you call post-industrial sexual commerce, right? What does that mean? What does post-industrial sexual commerce mean?

May I add one element to the previous question?

Please.

The other big intervention was actually the conversation around men who have sex with men so male sex workers, and hijra sex workers, who were a part of the HIV discourse but also a little on the margins. Still, the conversation was very important because it highlighted that there are men, trans people and non-binary people providing sexual services. And that it happens in many places, not just in red-light areas or brothels.

So, I’m going to your next question. The term post-industrial sexual commerce was actually introduced by the scholar Elizabeth Bernstein and what it’s referring to is how globalisation has pushed people to migrate. It has resulted in rearranged economies and in global flows of capital as well as labour. As a result, sexual commerce or prostitution has expanded and become more complex.

Today, red-light areas have changed and sex workers have been pushed out because often red-light areas are real estate gold.

People can’t afford to live in those places anymore, so they move out. In some parts of the world, these areas have a historical meaning to that city and they become gentrified and, you know, really hip, pub-crawl zones.

We also have sexual labour expanded beyond what was earlier understood to be prostitution. We have strip clubs, dance bars, massage parlours, other kinds of sexual entertainment that is expected in certain cities and gets integrated with other such businesses… And in many cities, getting clients to drink more is one of the tasks of those who are acting as hostesses in bars or clubs and who are also doing sexual labour. It becomes a club good in a sense.

Globalisation has led to sexual commerce having a big-business character—run by transnational sex industry, by big organisations, often the mafia. While this is a dominant view of sexual commerce because it feeds into the trafficking discourse, the truth is there are migration trails and women are migrating because their lives are precarious. They are being pushed to move for their family’s survival. There’s this image of the trafficker snakehead in this book called Chinese Whispers.

If you imagine this Chinese dragon with its head in the UK and tail in rural China—a channel for illegal labour to be brought to the UK to work. It’s such a great visual to understand how labour is moving.

Post-industrial sexual commerce is more a Western phenomenon because in India, we are not post-industrial yet. In the red-light areas, therefore, you see a mixture of activities. In Sonagachi, even in 2019, you see the older kind of sexual commerce (street level or based in red-light areas). And on the periphery, you start seeing women who arrive in the evenings. They have handbags. They don’t live there. They come to Sonagachi after they are done with their first shift for the day. They are [taking on] some extra work before going to their families.

The Internet is an important part of this shift in India and abroad. During the pandemic, sex workers began to provide services on the phone. It comes with new uncertainties and anxieties. All this exists alongside a resurgence of street sex work because of the economic knife edge people are living on.

When you think of the erotic world city that is the Internet, what do you make of the overlapping geography of the online world and of Mumbai?

In 2012, when I was doing this research, the red-light areas were already rapidly changing. Kamathipura was changing rapidly. The mobile phone, which was everywhere. Everyone had the China mobile. The bar dancer was also using the mobile now. Even though the red-light area was shrinking, it was impossible that commercial sex had disappeared. Women were disappearing but it’s impossible that commercial sex had stopped. Around the world, tech was enabling sexual commerce in new ways, but the digital divide in India seemed too huge [though] I wondered if it really was. I thought that some element of sex work continuing through the Internet.

The other factor was the EROTICS research, a multi-country study into sexuality and the Internet in 2009-10. Maya Indira Ganesh and I led the India part of that study and we’d found that the Internet had transformed the sexual rights of young women who were using [it]. They were expressing themselves online, putting up pictures of themselves, bypassing surveillance that happens in families and having relationships. They were learning to navigate violence online and accessing sexual health information on contraception, abortion, all kinds of things. It was really a game-changer. These were non-commercial forays into the Internet and sexuality. We hadn’t explored sexual commerce. But that was the starting point.

When I was thinking about sex work geographies and how has the Internet really changed the way we experience intimacy, this emerged as a gap. We had looked at intimacy but we hadn’t really looked at sexual commerce and how that was changing.

You note in your book that even as you were writing it, there were rapid changes on the Internet and that further changed the world of sexual commerce. What would you say was the big shift in this short time?

Someone told me, “I don’t even remember how things were before Tinder,” and I said, “That’s great. I have just the book.” My book is a pre-Tinder history of the Internet. Things become history really quickly now when it comes to tech.

Tinder came in 2015. Now, dating is more normalised with so many apps. I hear people say the apps are crap but how else do you date? How have apps like Tinder, Hinge and Bumble, and that whole ecosystem, changed commercial sexual encounters? I wouldn’t be able to answer this with certainty because I haven’t spent years researching it—unfortunately as sociologists, we have to study something for 10 years before we can comment on it. But a lot of the experiences that I explored in the book would probably now have shifted from the platforms they were on back then—mostly classified ads websites. Even escort service provisions would probably have changed.

Earlier, it was a big deal for escort services sites to somehow convey that women were there of their own consent, not something that was ever clear to a client in a red-light area. There was a preference for independent escorts because it liberates men from the burden of worrying that they are part of something forced or harmful to women. With Tinder notionally catering to the same preference I think there has been a cut in clientele for escort services, as well as a movement from Craigslist kind of classified ads platforms, to dating apps and platforms like Tinder.

It would be interesting to see how the sheer ease of tech (as opposed to having to host a website and create a front of respectability) where you can just put up pictures on Tinder, how that has also changed things.

I agree. And that’s the other big shift, right? The broader economy—the gig economy actually—the framework of work there, you know you can actually have independent transactions using the Internet based on reviews and comments. That is a framework to work in, a recognised economy of its own. With a term in itself.

It’s a point that I make in the book, that people who are offering sexual services online are saying constantly, “Look, we are not standing under a lamp and offering sexual services, so we are not sex workers like that.” I kept thinking that all they are trying to do is remove the stigma.

Then you realise that, “No, actually their experiences are completely different from women who do sex work in the informal sector.” Their experiences are more like gig economy workers.

For me, it was a conceptual shift. It fits more in the gig economy than the informal economy where traditional sex workers are located and sometimes when I say this, people ask, “So what? I mean, what’s the big deal, right? How does it change anything?” And I think about this, so what? But I feel that we can understand sexual labour a little differently if we think of it as something that is present in the informal economy, something else that is present in the gig economy, something else that might be present in the migration economy. You know we’ll understand each a little differently. Because the vulnerabilities of that broader economy are reflected in the experience of those who work within it. For instance, during Covid, street sex workers could not make daily wages, like many daily wage labourers in the informal economy. An escort service provider might experience isolation, as many gig economy workers do. If migration is unsafe generally, then migrating for sex work is likely to become an experience of trafficking.

As a corollary, we can then expect, or hope, that positive changes in the broader economy (like decent minimum daily wage in the informal sector, or spaces for unionising amongst gig economy workers, or policies for safe migrations) will influence the type of sexual labour within that economy.

That seems to have a big implication about how people think of themselves as workers. If you are a young sex worker who has grown up surrounded by examples of the gig economy, the way you think of yourself would be very different.

Yes, absolutely. And even the idea of temporary work. Sex work is not your whole identity. You could have provided some sexual services during a certain period in your life. And that is the reality. That is what sex workers do anyway. It doesn’t become your identity but being in a red-light area or part of an escort service also meant that you have the opportunity to find a community. Otherwise, for online sex workers, isolation is a huge issue. If you are working in a red-light area or if you are organised, you are part of a collective.

Online sex workers, male and female, think this is temp work. The minute I finish the loan, I will stop. Once I am over this… which is a feature of the gig economy. The benefit: you don’t have the sex worker identity. The problem is that you are alone.

You don’t have a community, a collective, no collective bargaining. If we did see them as sex workers, they could create standards to make their work safer.

Now we wanted to ask you about our favourite line in the book where you say, “Recent literature shows that some commercial sexual encounters mirror non-commercial ones.” How do non-commercial sexual encounters, such as a dates or sex within marriage, mirror commercial sexual encounters?

We have preferred not to see, or preferred to unsee, the sexual labour of housewives or of girlfriends. Older Marxist feminists had some framing of this. That housewifery as an occupation involves sexual labour: when you make sure you’re looking very nice when your husband comes home from work, the labour of lovemaking and providing what we understand as ‘conjugal rights’ in legal language.

Housewives have to do sexual labour along with the unpaid household labour, childcare and eldercare.

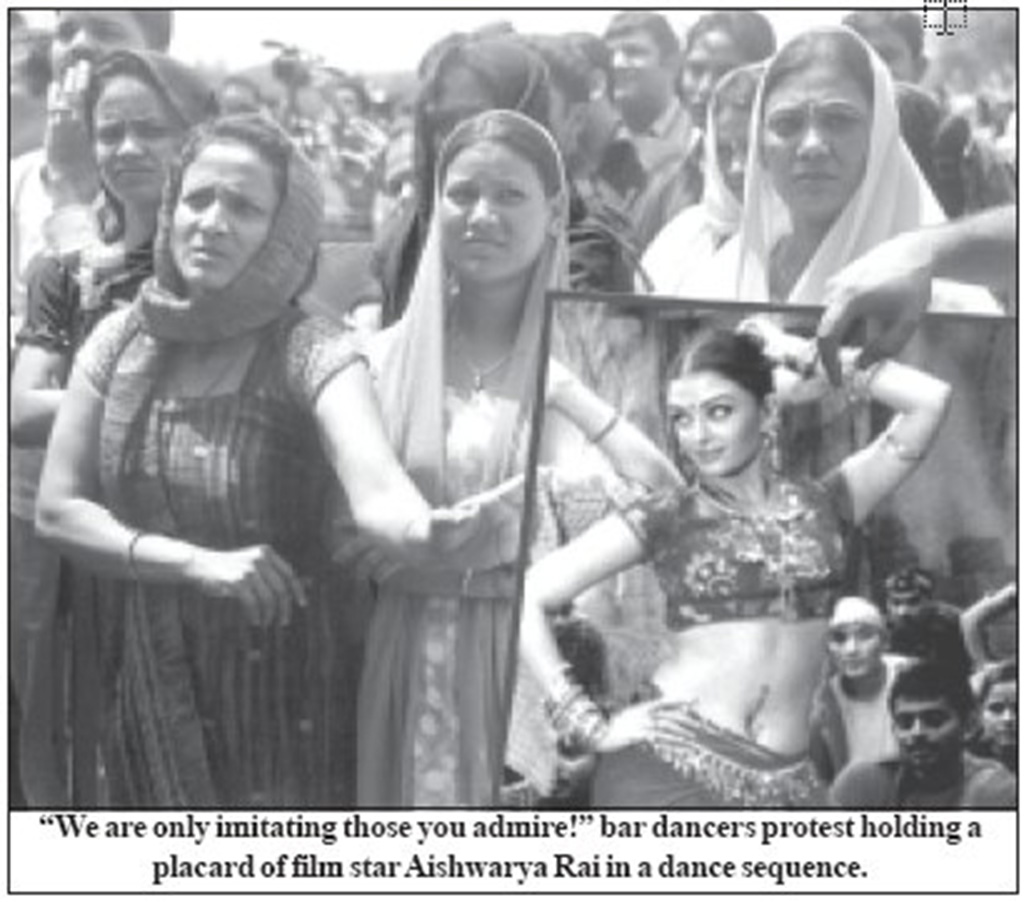

This parallel exists in the popular understanding. I think it’s in Arth (and I remember Mahesh Bhatt’s quotes emblazoned on the Stardust cover) in which Shabana Azmi tells Smita Patil (Patil is the Other Woman, Azmi is drunk, they are at a party), “In our Shastras, a good wife is supposed to be a mother to her husband in the morning, a sister in the day, and at night, she has to perform the role of prostitute in the bed.” I don’t know if it’s Shastras or if it is just Mahesh Bhatt whom we should attribute this quote to but in popular culture there is an understanding of the sexual labour [of] the housewife and that’s an aspect that we don’t talk about: lovemaking as a chore. More recently, Alia Bhatt in and as Gangubai Kathiawadi (directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali), delivers a climactic speech in Azad Maidan where she frames sex work as profession, commerce, labour, and mentions sex workers serve the wives as much as men by catering to their sexual needs to take the pressure of the wives, so to speak.

In popular culture, the other thing is the housewife and the sex worker set up as competing vendors of services for the same customer—the married man.

When I was doing my research it was so clear. I heard the accounts of housewives who were doing the occasional fun-plus-earn model. They provide sexual services to NRIs and so on. There the housewife is also a sexual service provider. Then, we had situations where the housewife was the client. Or the housewife is also a category of services that the escort service provider would offer.

And the commercial sex worker is also a domestic entity, no?

Exactly.

When we look at the intermingling of commercial and non-commercial sexual encounters and how they are also happening in the same space, how do you think it has inflected feminist conversation about consent, about labour and other issues.

I can’t generalise so I will speak for myself.

The way I think about other things… For example, I do think that what is commercial and what isn’t is a tricky one. I think how sometimes there are exchanges in kind, not necessarily in money but holidays, gifts, meals, even friendship. One of the male sexual service providers talked about how for him the biggest thing he was receiving was actually these friendships. They were not real friendships but companionships. He’d talk about how it’s so important to mitigate the loneliness that he feels in the city. These are not long-term relationships. They don’t often use their real names. It’s not going to bleed into their real lives.

It’s a secret life and it’s transactional in many ways but the reward or the receipt of friendship is extremely important in that context.

The other thing I thought a lot (after my research) about was how our desires are so culturally coded. I had one male sexual service provider who told me about one of his favourite experiences was travelling with a woman who wanted a suhag raat experience. She was a single woman and she wanted the hotel, the bed covered with flowers, for him to wear a kurta pajama, for her to wear a bridal sari and they would perform the suhag raat. That was her fantasy.

Then there is this strong appeal of accessing upper-caste women in the escort websites. The names are all Natasha Oberoi, Sonia Mishra…

In the earlier EROTICS study, we noticed that all the men were calling themselves Rahul Malhotra. Because everyone is looking for their Rahul.

The work of creating those specific desires is done by our social reality and Bollywood.

Do you feel like there are areas in sexual commerce that you wish were researched much more in India?

Yes, absolutely. I think this book was really just exploratory. Generally, experiences of escorting and other kinds of sexual labour like massage parlours, non-organised sexual labour, the isolated sex worker, we don’t know too much about that yet. We don’t know about rural sex work in the way that we know about urban sex work. What happens after women are rescued, you know? That tracking… that has not happened also. These are just like off the top of my head, really. Some of these big gaps and as you enter one, more gaps will open and new sets of issues.

The big area I would love to read more about? Research about women as clients. I wasn’t able to speak to [them]. I heard of them through male service providers who spoke of their clients very lovingly. A lot of men said, “I didn’t realise the people I met would be such nice people.” I kept wanting to speak to these nice people about their lives! Women as clients and men as service providers are both important areas because, in a sense, sex work is a feminised occupation, right? It’s not a macho occupation or something to be proud of but men who spoke to me, they did have a very strong sense of some achievement in some way, which is different from how women talked about sex work. For instance, men never talked of themselves as sex workers; it was always that they were giving a service.