My first meeting with Annu was over a Zoom call at 7 pm on a Thursday. The past few months I had been meeting with women from rural areas and kasbahs who shared with me their stories of being ekal (single). That Thursday I waited in my office to connect with her after everyone had left for home. At my workplace, we often talk, and joke, about my ekal dincharya, my daily routine as a single girl in the city. “Mujhe wapas kisike paas nahin jana hai (I don’t have to go back to someone),” I would say, as I set out for my evening ghedi (roaming around). As liberating as that sounds, it did sometimes bring on a pang of something I didn’t have words for. Until I met Annu.

Annu had said she could meet me anytime after 7 pm, emphasising, “Shyam ko 7 baje ke baad mera apna samay hota hai (Post 7 pm is my own personal time).” This one line made me smile; I, too, cherished that moment when the clock struck 7. What was it about the sky, the colour of dusk, which felt as one’s own? It felt like a threshold, a thin line, waiting to be crossed.

At 7, I logged into my Zoom account and waited for Annu. She logged in but her video was off for the first few minutes. I asked her if she had proper Internet connectivity where she lived. The voice from the black screen responded, “Yes, but only sometimes. Internet is like a lover who makes you wait.” Her video finally came on. It took me a few moments to register the topography of her face and to gauge her location. “This is my room in Kekri, a tehsil in Ajmer, Rajasthan,” she replied without me asking. I had prepared a set of questions to get to know Annu, the single woman. But all my queries took a backseat as soon as we started talking. The rooms we came back to connected us instantly.

“Jab koi nahin dekhta, meh toh yahan aake naachti hoon. (When nobody is watching, I come here and dance).”

This was serendipitous. I too hop, move and dance in my now-vanishing, Delhi real-estate institution: the barsati. Later, when I visited Annu to meet her in person, I found her room also was on a terrace, although they don’t call it a barsati in Kekri. She had arranged for a small tank outside her room and built its stand to store water for her daily use. There was no motor to draw it from the ground up to the tank. It was all manual and she took pride in describing how she had pursuaded her landlady to get this done.

“Akele rehke aise bahut saari cheejen khud se karna seekhi hoon (Ever since I started living by myself, I have learned to do many things).” Annu, at 31, had many insights on the nitty-gritty of living the rojmarra, the quotidian, which has ekal at its crux. More than the story of how and why she is single, I wanted to understand this delicacy of touch: the way she wove space and time.

I asked her if she would share that with me and she logged out saying, “Aa jao hamara des (Come over to my land).”

थम तो चालो साहिब जी (मालिक साह) रा देस

बताईं दा थाने भावनगरी

भाव नगरी हो हेली, प्रेम नगरी

— Gulabi Das

(Come to my land, my dear friend, I will show you the city of love, the city of feelings.)

There was no train to Kekri. I first went to Ajmer where we spent a day together. Annu’s natal family lives in Kishangarh from where she commuted to Ajmer and Kekri when she started working with MJAS (Mahila Jan Adhikar Samiti), an organisation working for women’s rights. As we sat near her favourite Anasagar Lake, she looked at the city as a landscape that built the possibility of khudse karna aur banana (to do things on one’s own and make new pathways).

“I learnt three things working in Ajmer. First, how to walk in a crowd without being scared; second, how to be different from the crowd and not to blindly follow them; and third, how to travel alone.

“Not only Ajmer, when I travelled to other cities also, they were constantly teaching me something or the other. Kekri taught me to run in the fields and document stories; Jaipur taught me that you can go anywhere at any time, wearing anything you want. I am single and these cities are my relationships. I evolve with them.”

She summed up this affair with the cities as, “Ek kathasamudra mil gaya hai jisme aap gote khate raho. Aap tairna seekh jaoge, duboge nahi (I have found a vast ocean and all one needs to do is keep diving. You learn to swim, no need to worry about drowning).”

I felt the same about these cities that lived in me. My return to my native place, Baroda, from other cities felt like a woman bringing new thoughts, habits (uthni-baithni, taur tarike) from an affair, back into a marriage. How do you distinguish between what stays with you and what you leave behind? It was like the dense cluster of turmeric roots.

Gulabi Das writes:

हल्दी पतंगिया रो रंग उड़ जाएगा हेली काल की घड़ी

काल की घड़ी हो हेली काल की घड़ी

(That beautiful turmeric colour on these moth wings will fade when the time comes. That time, my dear friend, that moment.)

Annu and I left Ajmer the next day and went to Kekri—a bus ride of approximately two hours through a wide expanse of brown-and-yellow land as far as the eye could see. We got down at the bus depot, packed our lunch—dal fry, jeera rice, ratta ka paratha (stuffed, deep-fried paratha) and buttermilk. We drank sugarcane juice and walked to Annu’s room, about three kilometres away. There were no auto-rickshaws to ferry us. “How do you travel to places here?” I asked, sweating profusely. She said, “Chal chalke (on foot).”

In her one-room home, there was a place for everything. “I have assigned space for each activity: one corner for cooking, another for study, one for sleeping, another to rest, relax and stretch. It is like having four rooms in one!” We sat in front of the cooler, taking in its refreshing air in the middle of the heat wave in Rajasthan.

Everything in her room spoke of her. It was her curation. She said, “Mein apne room ko achche se clean karti hoon. Woh mera space hai. Meri tarah woh bhi sundar dikhna chahiye.” (I keep my room clean. It is my space and it should look as beautiful as me.)

I was reminded of Virginia Woolf’s essay, A Room of One’s Own, where she writes, “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” What would she say about Annu’s room in Kekri in the 21st Century? There was more than writing and money to this room. It had the routine and the stamp of the ekal.

***

Annu’s routine began with waking up at 5 am. Why so early? “For my cup of tea.”

Five am is the only time when other tenants do not bother her and the landlady isn’t awake. There is no fear of drunks teasing her. There are no brawls on the street and no other noises to disturb her. This cup of tea is very important to her, a morning moment of zen when she listens to some lectures or experts who make her think.

After this she prepares a meal that doubles as both breakfast and lunch—one and a half rotis and sabji for the morning meal and ditto for the afternoon meal. She then heads to a private library, where she pays for a desk to study at for about nine hours a day. Annu wants to be a teacher and is preparing for the competitive exams. She returns in the evening at 7. She would have stayed on late had the roads were safe to walk back alone. It was around this routine that her room was structured.

“I need space and time to study and only Kekri could have offered me that—it is affordable and it lets me sit without having to respond to a thousand other things, people and responsibilities. Here, I can study by myself and think about myself. After being on the field with MJAS for many years, this is the first time I am taking a break to study for myself.” She adds

“Apne aap ko samajne ke liye koi itna time nahin de pata jitna mein akeli rehke de paati hoon. Toh aap akele kaise huye? Aap toh apne sath ho na!” (No one can give as much time to understand the self as I, as ekal can give to myself. So, how can you say I am alone? I am with me and that counts as a companion, doesn’t it?)

Annu was not scared of feeling things and saying them out loud.

We walked another three or four km around Kekri in the evening. I realised there wasn’t anything in the landscape that could be included as an evening pastime. Usually, I spend my evenings galloping from one corner of Delhi to the other in Ola/Uber rides. The Outside was home to me if I didn’t have enough money for some places and didn’t feel safe in others. But my evenings were filled with being Outside. I couldn’t understand the evenings of Kekri.

When I asked about this, the locals laughed and said, “Time hi kahan milta hai.” (We don’t get time to think or complain about this.) Annu had a different response though. She had lived in Jaipur for a while. “Wahan ki shyam dekhke laga ki kitni jagahon par khudke saath baith sakte hain. Yahan woh jagah nahin hai. So, I come to my room.” (Evenings in Jaipur made me feel there are plenty of places you can go to and be with yourself. Here, such spaces do not exist. So I come to my room.)

Once back in her room in the evenings, she spends an hour stretching and meditating. It is as important as the morning tea for her. She has an image of Shiva on one side and Ambedkar on the other. Shiva is someone who inspires her to meditate and take care of her body. Ambedkar motivates her to take care of her mind and spirit. “Therefore Ambedkar is for everyone, not only us as Dalits.”

After taking care of her mind and body, which she says is as important as her work, she prepares the last meal of the day, which is usually dalia porridge with buttermilk. She keeps the dalia roasted in a container. She boils it for seven or eight minutes and sets it to cool under the fan. She then mixes cold buttermilk with it and the combination works as a coolant for the body in the hot weather.

“I don’t mind eating the same thing every day.”

Both of us had a little dalia together that day and I realised that I relate to her the way I hadn’t so far with most of my folks—people from my hometown, my friends from college, people I grew up with. A day in our lives was marked by how we navigate the self, away from our kin and relationships; not only marked by their absence, but also they were not present as active agents of our lives. They were either in our phones or in our towns we had left behind. Here and now, we were mapping ourselves, architects of our city.

“Remixwale gaane chalte rehte hain, wahan dalia pakta rehta hai, meh baal kholke naach leti hoon aur lagta hai jannat yeh hi hai.” (Remix songs keep playing in one corner, the dalia is cooking in another, I let my hair loose and dance. For me, this is heaven.)

Was this what our City of Feelings looked like?

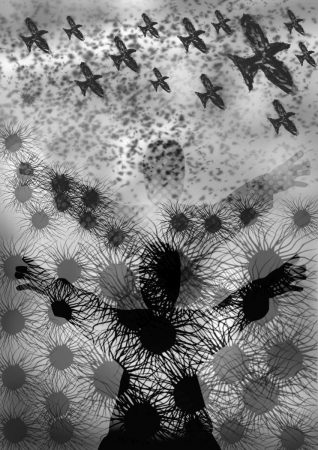

Something was simmering deep within me; building and collapsing simultaneously. I couldn’t understand this feeling, couldn’t name it and yet it had deeply moved my core. What was it that Annu’s room and kasbah had offered an insight into?

As Gulabi Das says in the song Bhavnagri,

काची कली हो कचनार कारीगर काया अजब बनी

अजब बनी हो यामे ऐब घणी

(This beautiful blossom of a kachnar tree has been crafted by that craftsman. But it is so fragile, so destined to break. It’s beautiful but ephemeral.)

And so is ekal—crafted like a kachnar tree but destined to break. It doesn’t stand still or content all the time. Was this pang the sense of knowing that it will break? That all we have built and are building can collapse any moment? The thought of this collapse felt unforgiving.

This feeling, or awareness, stayed with me throughout the night. I smiled as I looked at Annu. Could she see the turmoil on my face?

Looking at the night sky from her terrace, she said, “Mujhe na, kabhi kabhi lagta hai ki isko prayog ki tarah dekhna chahiye. Kahi kuch bana hua nahin hai ki aap pahoch gaye aur ho gaya.” (Sometimes, I feel that we should look at this as an experiment. There is no defined or destined way where one reaches. It will never be done.)

Even as she spoke, I could feel and name this duality of feeling: both liberating and painful. It was like collapsing into an embrace! It was acknowledging that I want to be held and that I don’t always have it together, that I need help and support.

Documenting Annu’s room, tracing my own room within its contours and that of our cities, were, in many ways, acts of resilience. But when I met Annu, it also felt like resting a while amidst the constant need to make sense. Just like the dusk colouring the sky right then, we had taken a pause. The sharing of the dalia also felt like an embrace. This is our bhajan, Gulabi Das, that helps me and my friend visit the city of feelings and love, the city of ekal, the visual image of our bhavnagri.

As a single woman in a megapolis like Delhi, I am oblivious of people like Annu who are neither in my imagination nor in my surroundings. It took working with a fieldwork-based organisation, connecting on Zoom calls and crossing states, cities and kasbahs to get to meet Annu. Our rooms were different from each other, the gaps as vast as the geographical distance between us. I hadn’t anticipated that a woman from Kekri who danced as the dalia cooled would respond to the word ekal and help rebuild me and my choices.

“Ekal hoon toh yeh nahin hai ki mere saath pyaar nahin hai. Mera akelapan mujhe freedom deta hai aur uski wajah se mein apne aap se pyaar kar rahi hoon, woh bahut badi baat hai (If I am single that doesn’t mean I do not have love in my life. My solitude gives me a sense of freedom and I am able to love myself because of it. It is a big thing),” she reiterates as I wave goodbye.

I couldn’t leave Annu’s room. Whenever I switch off the lights in my room, lamp on one side, books on the other, the ‘high as hope’ frame hanging on the wall—an entire room/nagari to myself—I imagine Annu doing the same, her DIY lamp on her study table, books covering an entire wall to her left, along with Ambedkar’s frame, an entire room/nagari to herself.