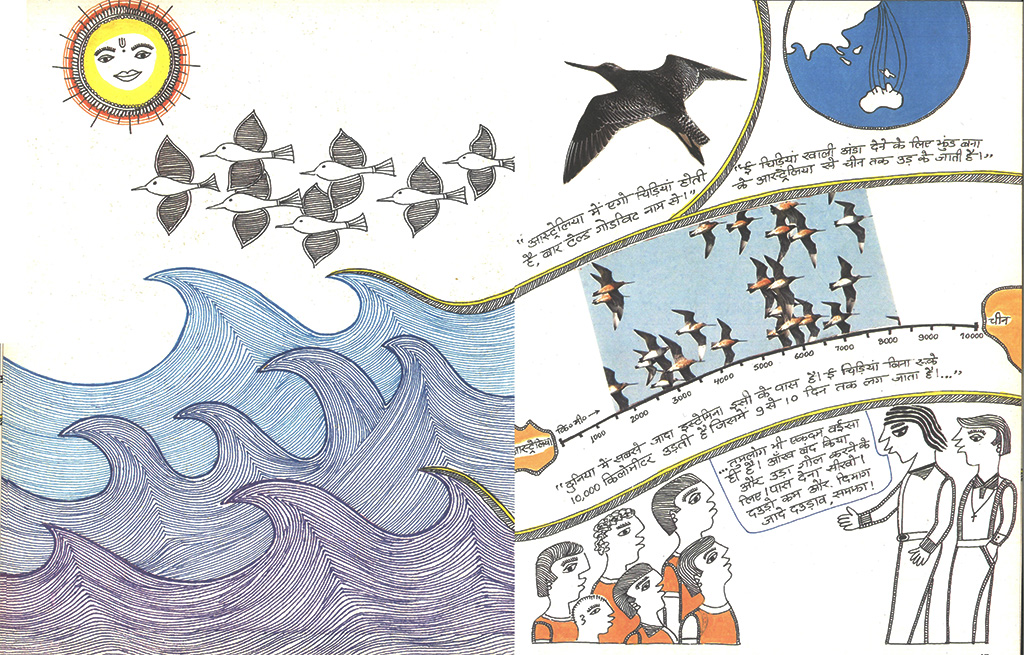

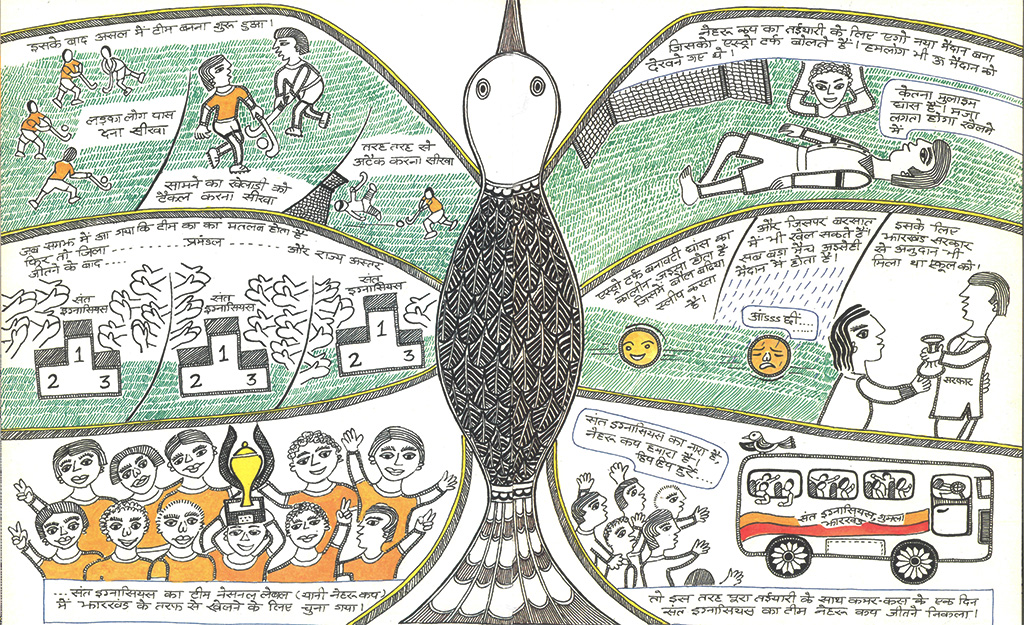

At St. Ignatius Boarding High School, Gumla, located in the hilly area of the Adivasi-dominated Chota Nagpur, Jharkhand, Hindu children chanted the Saraswati prayer, Adivasi children sang an ode to their goddess Sarna, and Christian children went to church. They grew their own vegetables, and once spent three days cleaning the school after a storm. These are colourful stories, far away from the black-and-white boxes the world draws—Mr. Gudmudiya’s amazing English and Fr. Johannes’ easy knowledge; sometimes there is pride in getting the chance to play with a new football and at other times there is the joy of finding cool water to bathe during a sizzling summer.

But alongside begins the journey of knowing and understanding one’s identity, aspirations, love, deprivation, language, and culture; it is also the story of different ethos in school systems and of understanding the boxes drawn for children. When we say that children live in their own world, do we really understand the tools that they use to build that world? Reading Biksu’s story is like slowly opening a big window in a closed room.

Madhubani artist Raj Kumari studied engineering at MIT, Muzzafarpur, and then at NIFT, Hyderabad. She designs film posters and illustrations for children books. Vikas was her beloved cousin. And it was his letter to her that became the book she dreamt up. And her partner, writer-director Varun Grover, wrote the text of this landmark book.

The Third Eye spoke to Raj Kumari about the process of turning a letter into a graphic novel, experiences with education, and the continuous process of teaching and learning. Here are edited excerpts from the conversation:

What is the story behind the making of Biksu?

I went home for a wedding where my cousin Vikas gave me a 35-page letter. I read it in one breath. Honesty is very beautiful. Its unpretentiousness and originality were very attractive. While reading it, Vikas’ truth gripped me. In his specific story, I began to see the familiar process of becoming a human being amidst subjects like education, teaching, identity, inequality, home, love, friendship, deprivation, etc.

Whenever we hear the words “boarding school”, the image that springs to mind is that of an expensive English medium school in the mountains. But

Biksu tells the story of a missionary school in the jungles of Jharkhand, where children bring their own foodgrains for the year and grow vegetables for themselves. Despite this, the school opens up a world of different experiences for them.

Some children got their haircuts inspired by film heroes, first the Salman Khan haircut, then like Sanjay Dutt and then the Shah Rukh haircut; and when they heard the story of martyr Albert Ekka from Fr. Johannes, they got their hair set ‘Albert Ekka style’.

Biksu says, “When Fr. Johannes came, everything started improving in St. Ignatius. As a result, children were happy from morning to evening.” What better words can there be to understand the role of a teacher in our lives!

While reading the letter, I felt that something should be done with it. I showed [it] to my partner, Varun Grover, and he also read the entire letter in one breath. He also said that this story should be read by everyone. In Biksu, we have put forward all the expressions of Vikas’s letter in their spirit.

What was Vikas’s relationship with the school?

How do we see school? Along with learning to read and write, we also have so many other experiences, which become an integral part of our lives. At the same time, there are things that can never be integrated into our lives, come what may. In the process of education, we also form a relationship with our environment. Whether it is with a friend, hostel room or with the surrounding forest. They become part of our memory and merge with our existence. Biksu was also very happy with that.

Before Fr. Johannes came to the hostel [and made things better], Biksu learnt to eat rice infested with bugs, then he learnt to make fun of it, and then he learnt to be happy about it. The joy of getting a new football was so great that he proudly fulfilled the responsibility of washing the football after the game was over. He realised for the first time that day what a new football smelled like, and for many years, the smell stayed in Biksu’s soul.

But at the same time, he found it difficult to solve math problems or write a sentence in Hindi correctly. Looking at his grammar mistakes, people would say to him, “You are so big, but you can’t write a single sentence correctly.” But he also writes in his letter to me, “However bad the experience, its memories are always pleasant.” He makes such a meaningful observation with such simplicity.

But when we are stuck only wondering why he can’t write sentences correctly or why can’t he add a² and b², then who will try and understand how sensitive he is to his surroundings and his life? He may not be able to remember the dates from history, but he asks questions like, “Why do people fight amongst themselves?”

The fear of studies and exams that we instil in children one day turns into such a big monster that despite studying day and night Biksu feels that the monster is constantly at his heels. One fine day Biksu turned around and asked the monster, “How much can one study? I’m losing my mind. How much did you study for your board exams?” Taken aback, the monster said, “I? I failed. But all the children that I have scared till today have passed. That is a record.” He understood that if he was to defeat the monster of fear, he would have to stop paying heed to what other people said. Till date, I haven’t come across anything simpler to boost one’s self-confidence.

These two parts within education are completely contradictory to each other. We have exaggerated analytical qualities in education to a very large extent, giving them so much importance that we judge someone’s success and failure from them.

Despite this, Vikas’s letter has all the colours and fragrances of life, but there is no sense of anger or revenge anywhere.

Some people fit into a regular school system, while others try and manage to wriggle through it. But for students like Vikas, who are misfits in the system, it becomes very damaging.

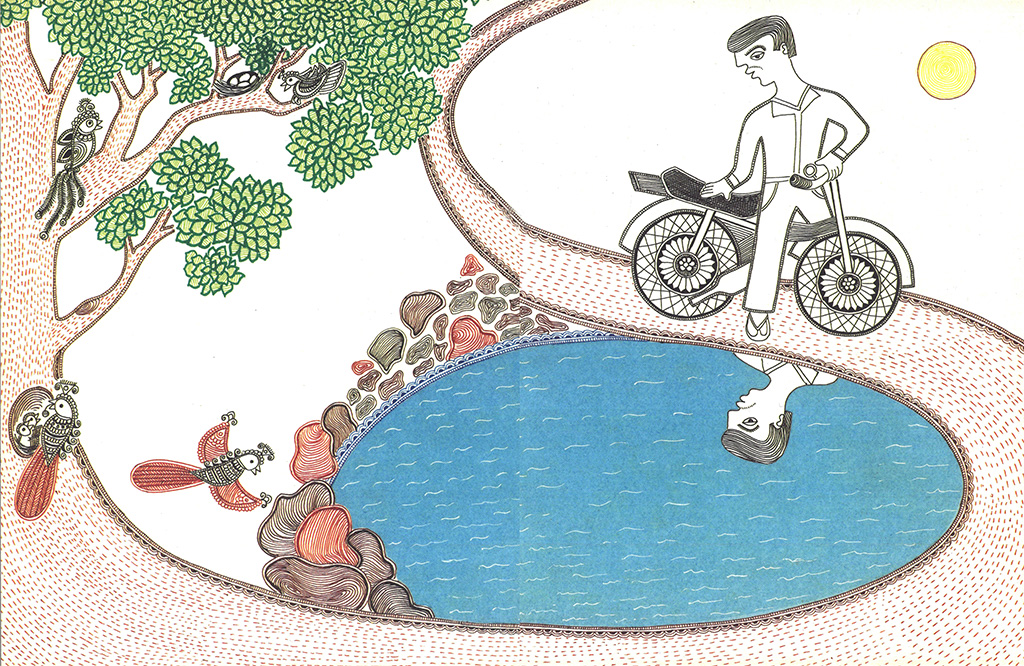

How did you manage to bring together folk art – Madhubani painting – and the story of a tribal Christian boarding school?

The first question that came to my mind was whether I should work in Madhubani or not. If yes, then how? For a long time, I kept asking myself if I was messing with this art form. And because of that, I couldn’t make it for years.

Madhubani is a folk art in which the culture of the village, and mythological and religious stories steeped in everyday life, are embodied. So, did that mean that I could not make it while living in the city?

I didn’t know the grammar of painting and I found the idea of working on a large canvas very scary. But Madhubani paintings attracted me, and I wanted to do something about it. That’s why I [came up with] this book.

I have always believed that folk art is an expression of the masses, and it breathes and moves forward, and thrives by staying among them. Based on this belief, I decided that when I make Madhubani, I would include the things that are my experience. I am not religious, nor do I believe in any rituals. I can’t make an idol of Radha-Krishna! But I can tell stories from around me through this art form.

Every art form has its own warmth and Madhubani has given Biksu that warmth.

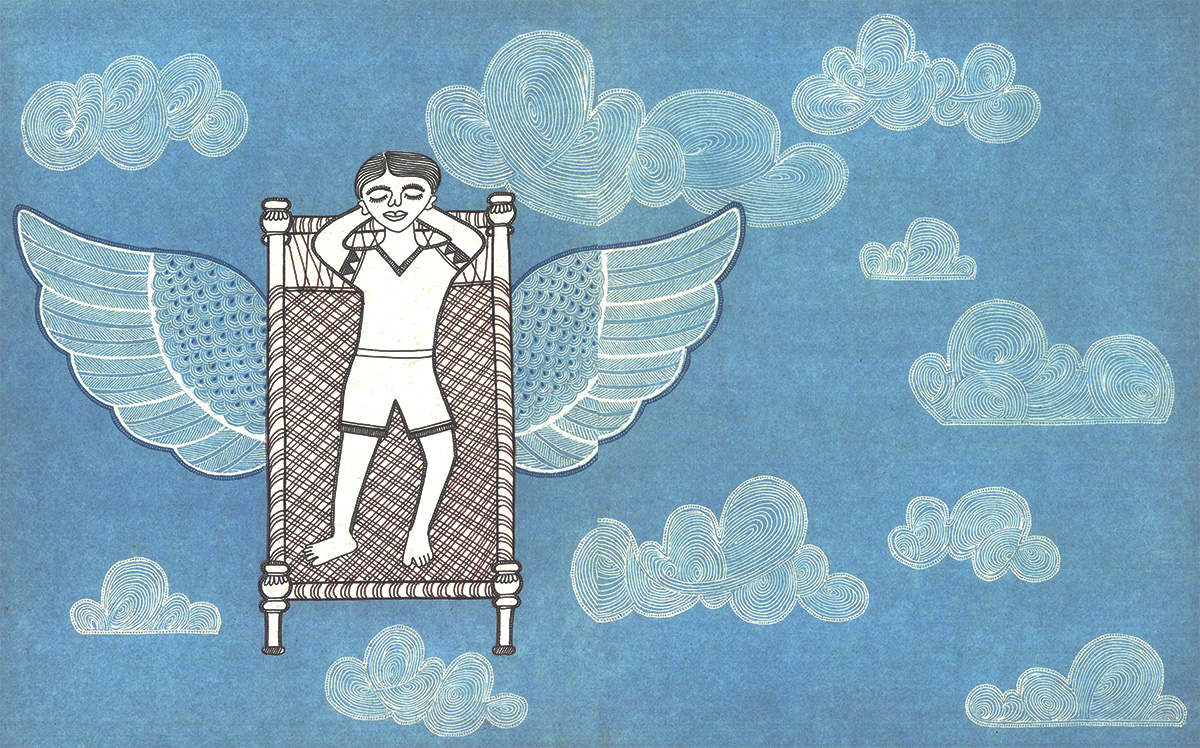

A child’s world—two-dimensional but very colourful, on the wings of imagination, new ideas creeping into the mind every moment and yet simple, vibrant, easy-to-understand—all these elements made Madhubani the ideal vehicle for Biksu.

The language in Biksu is Chota Nagpuri Hindi which is slightly different from conventional Hindi. Was the language a challenge?

Language was the biggest challenge for me … because it wasn’t just Biksu’s problem but also my own. My own language is Chota Nagpuri. Bihari dialects have an identity of their own. They are rhythmic to the ear. When I first came to Mumbai, I did not know English and my Hindi had a Bihari accent. This is popularly known as the ‘Bihari tone’ and the truth is that it is often viewed with contempt and made fun of. So, I had a lot of complexes about it. What happens is that what we do not know seems much larger than it actually is. And what we know always seems small in comparison.

Vikas did not speak the kind of Hindi that is used in Hindi graphic novels. Writing the novel in Hindi would mean killing his soul. But would anyone read Chota Nagpuri, which is spoken in a particular area of the Jharkhand state and does not even have a script of its own?

My aim was to tell Vikas’s story, and I could not do it by killing his very language. That’s why I decided to write it in Chota Nagpuri. This decision changed me a lot. It taught me to live with my language and be comfortable with it.

What happened next when the serialised version reached children?

The initial episodes of Biksu were published in Eklavya Prakashan’s magazine, Chakmak. One afternoon, I got a call from Sushil Shukla, the editor. He said that a little girl had come to his office with her father to ask, “When will Biksu come next?” She was so young that she could not read the magazines by herself. Her father used to read the story to her. Similar reactions from children, parents and teachers started pouring in from other places and then I thought, “Yes, we have created something that is liked by the children and their parents, and teachers.” Many children have also uploaded videos talking about Biksu.

Chakmak circulates in many villages, and we came to know that the book is being used to teach children in many tribal schools because of the distinctiveness of its language. Sushil told me, “Bundelkhandi is spoken in Madhya Pradesh. The children there have a lot of stories, but they do not write them because they don’t know conventional Hindi and feel like no one will read Bundelkhandi. But now they have started writing poems and stories in their own language for Chakmak. The things that seemed challenging at the beginning of the story became its beauty in the end.

Reading a story in another language does not just introduce you to the characters, but its entire environment comes alive. The life there, the people, the sounds, the fragrances, the trees, butterflies, everything…

This article has been translated by Maneesha Taneja. She works as Associate Professor at Delhi University.