“Time is going very fast…it’s very exciting…. for Hasina, is time going very fast?” ask happy, hopeful voices of a couple over a Skype conversation in the opening sequence of Surabhi Sharma’s 2013 film, Can We See the Baby Bump Please?, produced by Sama. The couple are going to be parents soon, though not in the way that we generally imagine. Hasina, if that is her real name, is their surrogate, sitting miles away from them, in a universe largely alien to them. In the following sequence, we see women in silhouettes, four of them, sitting in a row on white, metal beds that feel cold, and remind you, almost hit you with an antiseptic smell, the kind that permeates through countless, nameless hospital corridors. You hear the glass bangles of a woman, as she listlessly tucks at her hair. Through the windows in the background, you see the movements of an ordinary day, and the people that inhabit them, far away from these rooms. You see fragments of women’s hands, hanging limply from the ends of their beds, where they lie languidly. And then the front of a woman, and hidden behind the floral prints of her nightie, her bump. It’s very silent. Time, it seems to not move at all for Hasina and her peers. It seems to stretch. Weigh like a sack of bricks. This sequence in the film is about a minute and half long. But it feels like walking inside a tunnel.

Motherhood, one of the most romanticised, idealised, venerated, institutionalised concepts that a lot of us grow up with, grow into. Reproduction, generically accepted (and prescribed) as an important role of a woman, supposedly something that is ‘natural’ to her sex. A surrogate’s rented womb shakes up these normative narratives around a woman’s body. The unregulated surrogacy industry in India, believed to be nearly two decades old, is roughly valued at Rs. 16,465 crore per year. Ironically, the fundamental unit of this whooping business, the surrogate woman, is the least visible.

Surabhi Sharma’s documentary offers us a glimpse into a world that many of us know very little about. And makes us think about work in ways that we usually don’t; the reproductive labour of women who agree to bear a child for others, for a monetary compensation. Women known as surrogates, meaning ‘substitutes’.

Even before Surabhi began work on the film, the idea of the child bearing body intrigued her. “I was quite obsessed with the idea of the pregnant body, which I realised in a sense gets erased from family albums. You don’t take photographs of a pregnant woman, especially in India. It’s not considered auspicious…and pregnant women are constantly hiding their form…it’s considered something to be hidden, not to show off,” says Surabhi recalling her own pregnancy, and how “obsessed” she became with her own body then, “in a very positive way”. So, years later, when Sama – Resource Group for Women & Health approached her to work on a film exploring the universe of surrogates, Surabhi felt that, “…it was a natural progression to what I had been thinking about, so I got pretty excited.”

But, it wasn’t easy getting access to her primary “subjects”- the women. “I approached my activist and journalist friends for help, and asked them if they knew of any such women who had been surrogates, or wished to be…or if they knew areas where clinics approach women for surrogacy. I contacted a lot of people, searched in a lot of places, but drew a blank everywhere, because, very clearly, the issue of surrogacy is never spoken about openly, in public. This is always kept gupt, a secret.”

Surrogacy implies that the act of procreation enters the domain of market and transaction, outside the familial, the domestic. But the minute the labour of procreation is monetised, the 'mother' is stigmatised, her work is declared dubious.

We witness this otherwise as well, whenever a woman uses her body for paid labour. “The clinics constantly tell the surrogates that they should keep their work hidden from the world,” says Surabhi, when we talk to her about the dense world of surrogacy and the mixed messaging the women grapple with. “They tell them that if you talk about this publicly, people will compare you to sex workers. On the one hand, they tell these women that you are helping someone, and on the other, they send out a very clear signal that people will think that this is sex work and will humiliate and insult you, so don’t talk about it at all.” The surrogate’s womb, her reproductive capacity, is her labour. Her pregnant body, her site of work. But her work is either diminished, stigmatised or couched in altruistic terms in order to make it palatable for everyone.

“What does not talking imply?” Surabhi elaborates, “The clinics keep all the papers and the documentation of the women with themselves. Tomorrow, if any of these women have any health problems, they have nothing to prove that medically, their surrogacy had anything to do with it. I met a lot of women…seven-eight women…all they had was a prescription, post their delivery. That was their only piece of paper. But I feel that the women who are doing surrogacy, they see this as work. It is a means for them to earn some money in a lump sum way. So, their relationship with surrogacy is very clear. But no one is willing to see it like that.”

Surabhi recalls how most of the surrogates she met were primarily garment workers. Because the money earned through surrogacy was periodically given in large amounts, this helped them to make considerable investments with it, like for buying a house. So, a lot of the women, she feels, see surrogacy as “pure employment”, though whether they have any direct control over their income or not is moot. Interestingly, the ‘industry’ too expects the surrogates to honour a professional agreement- her performance and output determine her monetary worth. But sans any rights, any safeguards.

In the film, while talking about the surrogates and what is expected of them, the voice of a medical practitioner elaborates, “Their chunk payment is in the end…and every time, their payment is [made] after sonography and check-up. They know that if their results are not good, their next payment will probably be delayed by a week’s time. So, they take care. It’s not only an instalment and incentive for them…it’s like, ‘I have to work up’…because my next payment will be based on this particular sonography.” But the clinics have no accountability towards the woman in case of a health emergency, during or after her pregnancy. In fact, if the surrogate miscarries the foetus during her term, the clinics often do not pay them anything at all.

“If a clinic is promising a woman three lakh rupees at the end of her surrogacy, no one is raising the issue of how has this figure been arrived at,” says Surabhi. “If a clinic is taking 20 – 25 lakhs, say, 50 lakhs from the commissioning parents, so how did they arrive at this three lakh figure to be given to the surrogate? No one is talking about medical insurance, about how the clinics should be documenting all this properly, that this woman has been a surrogate in this particular year, and what has been the impact on her health five years later? There is no documentation or follow up of any kind. It’s like you release a new medicine in the market, and six years later if people start getting migraine because of that, whose responsibility is that? During the making of my film, all these questions became apparent to me.”

Given the secrecy and stigma that shrouds this industry, Surabhi was not surprised when none of the women that she had spoken to during her research, agreed to come on camera. “It was pure coincidence that one woman, whose voice you hear in the film, because she had had a miscarriage through surrogacy, and so in a way, she had been thrown out of the industry…she was ready to talk because she knew that she will not be able to become a surrogate again. All her money was cut because they said that it was because you went home in the middle of your term – that’s why you miscarried,” shares Surabhi. “The others did not want to talk to me, did not want their faces revealed, perhaps because they wanted to become surrogates again, and they had all been threatened by the agent that there are media people roaming around, so do not talk to them.”

The film stitches the faceless voices of these women, but there is a sensation of a certain presence. A presence of these women’s bodies that are never entirely seen, images that are never fully realized but only experienced in fragments, and voices that come and go. Their unacknowledged labour, only expressed in a handful of words. They are what make the film, and yet remain inaccessible, hidden to us.

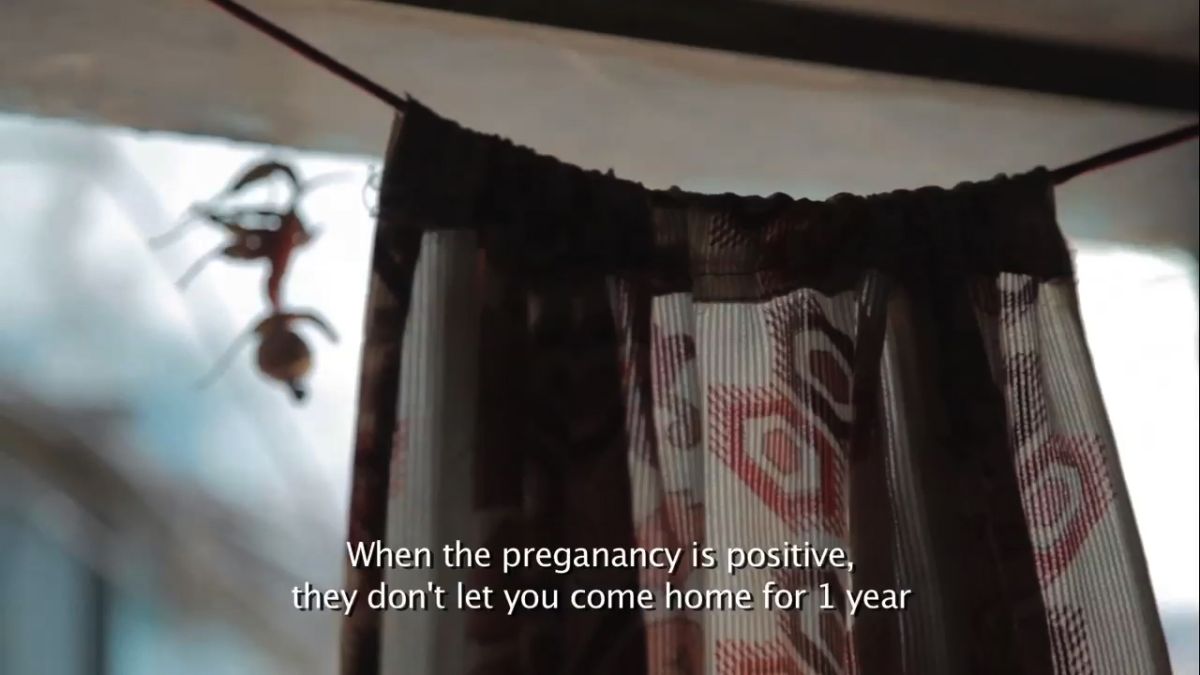

They cannot go home. They are not allowed to go home.

Surabhi is visibly agitated while talking about this. “They are sitting, for nine months, they are just sitting…. literally, like prisoners. Even today, when I talk about that aspect of their surrogate lives, so many years later, I get badly shaken up.” Sometimes, the clinics may hire a building, or a Chawl where a large number of women are stuffed together, like sardines in a box, no doubt to economize the costs. The rationale for the women’s captivity is the supposed risk involved to her womb in unmonitored environments. Her family members are allowed to visit her occasionally though. (The clean, relatively spacious hospital ward-like environment that we see in Surabhi’s film, she feels, may in reality be a “set” that the clinic may have “created” for her to film. It could be. It may not be. In a context where so much is tightly kept under wraps, it is hard to tell what is real, what a performance.)

For nine months, the surrogate is under strict medical supervision to ensure that the delivery is as desired. This is in sharp contrast to women’s own lived realities. In the film, a woman narrates how during her own pregnancy, she tried to get admitted in a hospital once she went into labour. But she was told that she had come before time and was shooed away by the hospital staff – “…The nurse slapped me two-three times and threw me out of the room. I pleaded with her, I knew I was going to deliver any minute…she argued that I still have two more days to deliver and asked me to leave. ‘Why have you occupied a bed, God knows where these people come from!’ She got me to get out of the room. In tears, I sat down by the stairs. I delivered my child right there.”

In the parallel world of surrogates, however, their health is given utmost priority. In another sequence of the film, women sit around and banter about how they don’t like “…Eating so much. But we have no choice, we have to increase our weight. These biscuits are so dry. But it’s not for us, it is for the baby.” They talk about how they get paid more if the child’s weight is more than satisfactory – “We will get Rs. 10,000 extra. And that too, if the baby is four kilos.” And then they joke about how they should add, “…one kilo in the nightgown itself. Or while weighing we should wear some stones around our neck!”

The one perspective that was clear and immediate to me was that the women who come to be surrogates, have no access to any form of health care themselves, in their own personal lives. But once the woman is a surrogate, suddenly an extravagant medicalisation process takes over her completely.

The primacy of herself, her ‘me’ is totally taken away from her.” The women undergo a closely scrutinised medical regimen – numerous ultrasounds, foetal heart monitoring, insistence on caesarean deliveries – decisions where, more often than not, they do not have an active say.

In the film, a surrogate who had miscarried in between her term, says rather pointedly, touchingly, “…It was someone else’s baby so the doctors took care. Only the womb was mine, the seed was theirs. So, they took care of something that was their own.”

What is the relationship between the surrogate and her womb? “Most clinics, not all, but most clinics, dehumanize this idea, this relationship,” Surabhi tells us.

They don’t let the surrogate see the child’s face even once. The excuse that the clinics give is that they don’t want the surrogates to develop an emotional attachment to the child.

So, they say that we are rescuing the woman from this trauma. And also protecting our own interests because if the woman gets emotionally attached to the child, she may not want to give it up and it may turn into a legal battle. This is all utter nonsense, because the contract is very clear about all this. Also, the surrogates themselves say it very clearly that, ‘We can’t take care of more children, we were not doing this for the sake of having a child. But we have carried the child within us for nine months, so why can’t we at least get to see what it looks like…how will this harm anyone!’ this separation affects the women deeply, and they speak about this with extreme gravitas. They constantly reiterate that they don’t want to keep the child, that they are happy that this child will have a better life than theirs, but at least they should be allowed to see what the child looks like.”

Surabhi says that while working on the film, it was impossible for her to ignore the “labour” aspect of surrogacy. And that while the question of medical ethics is crucial to address, it is equally important to acknowledge a surrogate woman, first and foremost as a worker. As a productive being who must be met with suitable, reasonable, fair compensations. Who must be placed within a circle of rights and responsibilities and not merely as temporary cogs in the supply chain. It is because of these reasons that the recently passed Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill (that bans commercial surrogacy but allows ‘altruistic’ surrogacy) came as a disappointment to her. The Bill purportedly claims to prevent exploitation of surrogates as well as commissioning parents by the hands of the fertility market. It bans all commercial surrogacy, only allowing ‘altruistic’ surrogacy within the space of the family.

This Bill has invisibilised the whole labour aspect of surrogacy, in all possible ways. Imagine that you are the youngest daughter-in-law in the family, and that the whole family has decided that I will play surrogate to my older sister-in-law…. I have no voice in such a situation, given the family pressure, and I’m talking best case scenario. Basically, payment has been removed from the picture.

Whatever little agency a surrogate had, that she was earning money through this, you have totally dismissed that. So, all the other vital things like medical insurance of the woman…. all those are too far-fetched now. So, there are huge, huge losses [caused by] the Bill.”

Again and again, the same questions repeat themselves. Who determines how the reproductive labour of a woman should be evaluated: the society at large; her family; the fertility industry; the state? And what of the volition of the woman who is at the centre of this debate? How can the terms of conversation become more equal, negotiable, on the same plane? For now, thinking rigorously about these issues is, perhaps, at least a promise of a movement.

Watch ‘Can We See the Baby Bump Please?’

Ruchika Negi is Associate Editor, The Third Eye.