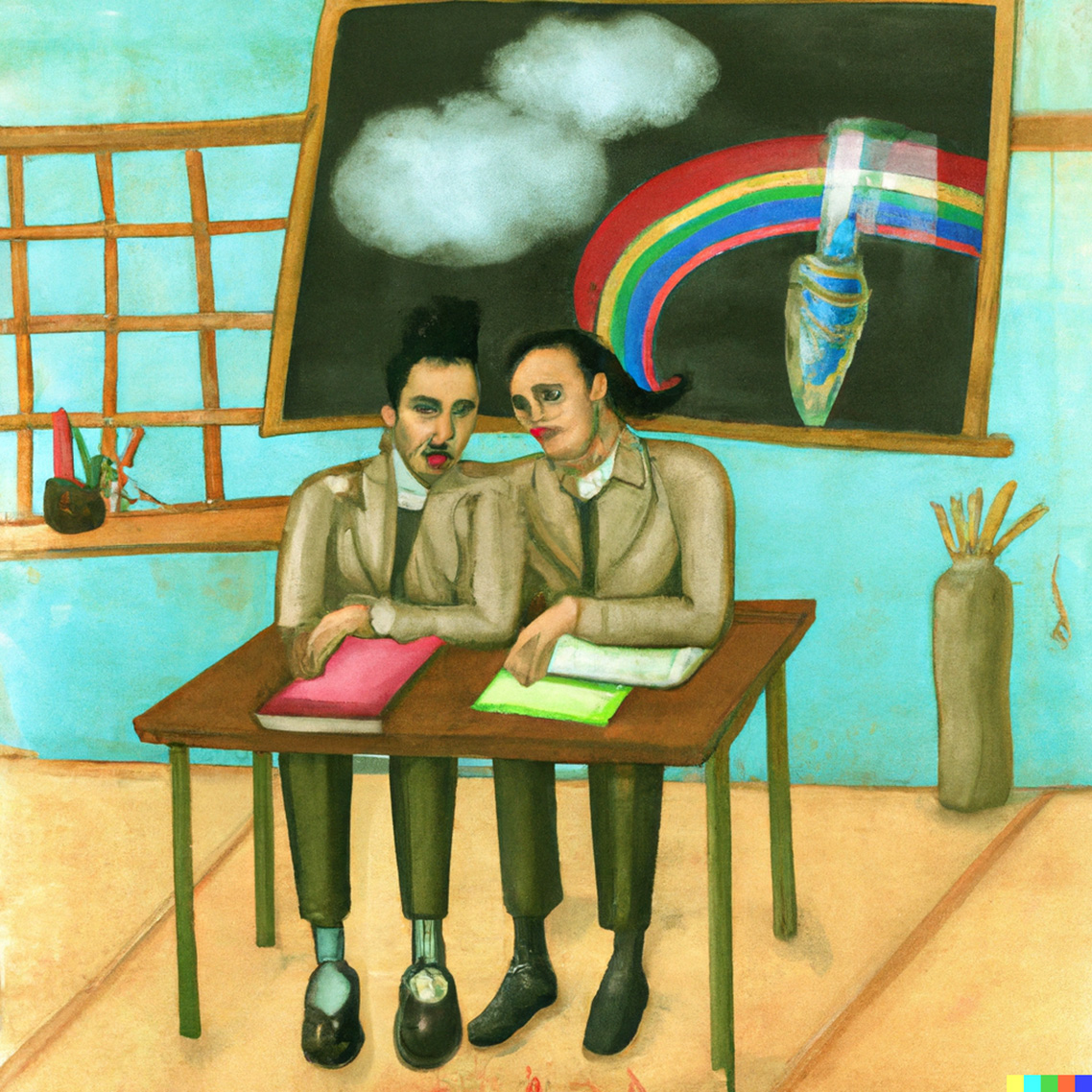

We learned about photosynthesis five times. Every year, from Class 6 to Class 11, I forgot the exact definition so I had to relearn it even though I knew the concept. In the same way every year, I had to relearn that the boys in my class would sniff me out.

It was not clear in the beginning. I learned it the hard way while playing kabaddi and they told me that I belonged in the other team with the girls and Anuj. Then it happened with water polo and then with football. Thankfully, I was bad at football so I became the waterboy entertaining the crowd in the corner.

One day my biology teacher called me Behenji Number One and Anuj, Number Two. The teacher called us those names to condition us into becoming more manly. These names officially stuck for two grades but didn’t fall even after years.

Anuj and I should have made a duet of the title song of Amber Dhara— the soap about the lives of a pair of conjoined twins trying to find dignity in a ruthless world. We enjoyed the song a lot. Jude Hain Do Sapne Jude Hain Do Kisse.

In retrospect, the conjoined twins were not us. It was the world and us. We were joined to the world by our hips.

We seemed different, twisted or maligned, but were truly looking for similar things like love, grace and acceptance. And learning things like photosynthesis with no explanation of life did not help.

After a while, I didn’t have to learn what photosynthesis was. Likewise, the thought that I was the sissy rolled into acceptance in my cerebrum.

But, perhaps, all of this would have been different if, instead of asking us to be something else, our biology teacher had asked us to see more in ourselves. Perhaps we wouldn’t have had to try harder every school year to reinvent ourselves into the men we were supposed to become.

Perhaps, then, the boys in our class would have understood that being a woman was not an insult.

As a barely surviving grad student in the United States, I had taken on the task of teaching creative writing to students one summer just for the money. My class was filled with middle school students with thick-rimmed spectacles and wiry constitution. On the second day, I asked them, “Tell me a story you all know.” They looked around screaming Iron Man, Guardians of the Galaxy, and Captain America, none of which I had watched.

“Could anyone choose a Disney princess story for now?” I nudged. Some of them giggled at my choice.

“Beauty and the Beast,” the boy in the front row said.

“Do we all know Beauty and the Beast?” I tried to reconfirm. The heads rocked sideways. No.

“All right, we will go with Cinderella then,” I declared and asked, “What does Cinderella want?”

The room was loud again, this time with whispers.

“I need words,” I cut through. “What does Cinderella not have?”

“A dress,” someone said.

“Well. For the ball – yes – but not quite,” I said.

“Shoes,” another added.

“Fairy godmother.”

“For the ball again,” I corrected.

“A boy,” someone said and I smiled as they inched closer to an answer.

“Prince Charming!” three of them bounced off their desks.

“Yes!” I cheered and then asked “But what does Prince Charming represent?”

“Money.”

“Shoes.”

“Love?” someone said.

“Yes, Cinderella was looking for love,” and like a proud mother bird, I chirped at them with applause.

The entire classroom, like a rollercoaster on a drop, went “Ewwwwwwww.”

Such a visceral reaction.

When and how do we learn that love was something to be disgusted with?

Perhaps it was overwhelming for them—to encounter the idea of love in the classroom. The classroom was a place where they were taught what disturbance looked like, what punishment sounded like, and what authority felt like. Was there any room for something else?

But it surprised me, this repetition of my own childhood here. Isn’t America supposed to be liberated? Where children were smart, mature and exercised their free will, where laws called for sparing the rod. It surprised me, yet I was delighted to know that my presumption was wrong. It was truly the space of the classroom that does not account for love.

*

One nippy October evening, I was invited by an Indian family for a Kongali Bihu dinner. My first dinner party in America. I dressed my heterosexual best by tying my hair into a neat ponytail and wearing a loose shirt. The hosts had two precocious children, one adolescent and one younger. They were heavily invested in getting straight As, a Grammy, qualifying for the Olympics, and becoming a doctor. The parents’ smiles shone not from a new brand of toothpaste but from sheer pride. The older one who wanted to become a singer asked me if I could look at the lyrics of a song he had written.

“Could you tell me what is working and what isn’t?” he asked.

The song talked about a boy who looked admiringly at a girl during recess. The stuff they sell in paperback covers and sitcoms about teenagers.

“Does your mother know?” I asked him sotto voce, like the brown aunty that I am.

“This girl is imaginary,” he told me and kept from any eye contact. I smiled, enjoying his skills.

Men learn deflection quite early.

“I see. In that case, I feel like this isn’t hitting an emotional peak. The person is just looking at the love interest. They aren’t doing anything.”

“I mean I don’t want to do anything. I just want to look at her.”

Truth be told the song just needed a chorus. But the way ‘I’ slipped carefree from his tongue felt tender. Even with the knowledge of deflection, he has not yet mastered conceit. That lack of walls around his emotional self warmed me. He did not know that when he said he wanted to look at her, he gave away a part of his truth.

He was at the precipice of something that every other self-respecting adult in my lifetime had told me never to do while at school—fall in love.

Asking him to ‘do something about it’ was just an excuse to tell him that there was merit in seeking to unravel our interest in someone else even if the cost sometimes was rejection and therefore doom, of course.

But could I suggest it? Right in front of his parents who already had so much to handle as they hosted 25 guests. Out of courtesy, I stopped myself and said, “You may need to work on the chorus. Think about what it would mean for the character to be heartbroken,” and moved on.

Not soon enough the younger one, with his nose inside his PlayStation, asked me, “Do you have a girlfriend?”

“I don’t,” I replied through a dent of smile on my face.

“Do you have a boyfriend?”

“Not yet.” I was amused this time at his question. “Naveen, why did you ask me about my boyfriend?”

“I don’t know. Because you are old.”

The answer offended me a bit, to say the least.

“How old do you think I am?”

“21,” Naveen’s opening bid.

“No.” Relief.

I wanted to know what would happen if I peered into his life the way he did mine.

“Naveen, do you have a girlfriend?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“They are a distraction.”

“They don’t always have to be.”

“No, no, it’s a waste of time.”

“Why?”

“I have tennis and books to focus on.”

“But how do you know you will waste your time if you haven’t had a girlfriend?”

“I am too young.”

The French called this feeling coup de grace or the kiss of death.

The youthful body is most primed for love. It is defined in lyric and marble as the most potent receptacle of desire. I had witnessed that under the same roof, one brother had sniffed out the wasteful nature of youthful longing, while the other wanted to sing a praise to it.

This is a dilemma that youthful minds constantly have to deal with.

If nothing lasted against time, nothing can be unmoved by youthful glory. A few months later, I was invited to another party at their place. It turned out Naveen had naturally distracted himself with an interest and asked me to not tell his mother.

Once, in my school in Guwahati, students were lined up to be punished. Two seniors, Tareeq and Sushma, had been caught holding hands in the corridor.

We stood there staring, wiping sweat off our foreheads, hands moving like the tails of cattle fanning off flies. Our Class 7 Math teacher had come in and shooed us with a textbook.

All of us in the crowd stared at the punished crew on the ship of young love.

As we moved into class murmuring about what would happen next, the Math teacher opened the textbook and said one thing to all of us in order to rationalise what we had just witnessed. “There is a time and place for everything. This is no age to fall in love,” he sermonised.

I already knew the cut-off percentage to go to St Stephen’s. But that was when I first wanted to know what the age to fall in love was.

School looked like—skirts not below the knee, hair not an inch longer than the thickness of a forefinger, and a white uniform without a single stain on it. Some of us had failed to get admission at Don Bosco or St. Mary’s, the premier all-boys and all-girls Catholic schools in Guwahati. So, our teachers borrowed discipline from those schools to keep parents satisfied.

And so, it seemed that Catholic School followed us and so did a girl with the alien accent.

Rumour had it that the students at the all-boys’ and all-girls’ schools were sneaking out of their education to bond with each other. The walls failed to contain desires. As soon as the girl’s parents got to know of this, she was taken out of St. Mary’s… and put in our co-ed school.

We fawned over her alien tongue that we figured was two-quarters British, one-quarter American, and the rest plain Assamese. A girl has to laugh, and when she did, all her accents dropped to the floor like ornaments off a Christmas tree. That’s how we knew the concoction.

Back to when Miss Nidhi found Tareeq and Sushma holding hands in the shadow of the playground slide. Tareeq’s lips and chin had just sprouted hair and they moved like ants when he talked. She, on the other hand, had just figured out how to roll the kohl just so to make her eyes sharper. Across the length of the entire field, Miss Nidhi saw them rub their shoulders against each other. She dragged them to the Headmaster’s office.

Miss Nidhi must have been awarded some kind of medal, we thought. After all, she had caught two worker bees and that was all she needed to find the nest aka information about coupling adolescents. It was inauspicious for parents to come to school outside of the monthly PTMs. The teachers knew that and threatened the couple that unless they disclose all those who held hands they’d better prepare for their coffins. Like in any other story, the fragile couple sacrificed other people to be spared some wrath – wrath they didn’t escape.

The parents came to school within the next week. Pairs of parents were seated next to each other and asked to profess hate for their child’s lover. We gossiped about how each parent was planning on locking their daughters up or sending their sons to army school.

There were so many rules against engaging in love. So much fear of getting caught.

Yet the only thing people wanted to do for fun was to be in love.

And almost immediately everyone was back in school, back in love and hating themselves for all the trouble.

I wish we were taught how to love. Perhaps we wouldn’t be so hateful as adults now.

I had broken through one of the hierarchies amongst the caste system of Delhi Public Schools by getting into one in Delhi. After three months in DPS RK Puram, when I visited DPS Guwahati, people either thumped my back in congratulation or warned me.

“Don’t smoke or drink.”

“Don’t fight with the Delhi boys.”

“Don’t forget your mother tongue.”

All of these warnings were beautifully wrapped up in concern and encouragement. Most teachers asked me what I wanted to do next.

Just like sandalwood reminded one of the temple, two moments in that visit reminded me of why I wanted to leave for Delhi.

“You need to prepare for IIT. I mean I am not saying you will get through if you prepare for it,” my former physics teacher paused. “But if you prepare, then at least you will get through a decent NIT. So, don’t distract yourself.” She smiled widely: her tobacco-stained teeth had painted her lips a beautiful rouge. Perhaps it was a victory on her part as a teacher to be able to ground me. I accepted it then with fervour.

The next gift I received was from my former economics teacher. “Well, whatever you do, if you get a girlfriend you will ruin your life,” she said.

The stakes were high. I could either go to IIT without a girlfriend. Or remain without a girlfriend after IIT.

*

One evening I was telling my father how school had ruined the experience of love and he told me that teachers have to do that else kids would become unruly. Sure, we were left with acids in chemistry labs but talk about love and everything would disintegrate.

Like most schoolkids, I was not taught about love but I knew about sex. We would talk about pornography through jitters of adrenaline and laughter. It was clear we knew things we were not supposed to. And concerned parents would bash us.

I am still understanding what it means to love. But if I had to travel back in time the only thing I remembered was how horrible it was to even think about love. Yet it was everywhere. Our intention to fall in love was partly inspired by what we saw on MTV and at the movies. Every singing contest had someone singing Saiyaan.

At the same time, love felt more than just that. It felt like the very fabric of life was informed by when, where, and how we loved. This electromagnetic pull was so heavy that it dragged us all into it— in thought, action, and laughter. While no one within our classrooms allowed for, let alone gave us space, to accept that such was life. That in this wonderful life we will find something to love and that sometimes that something to love will be us too.

I think every one of those adults knew what love could do—change all orders and designations and equations.

One day when the hot loo winds of Delhi exhausted us, a friend shared her tiffin with me.

She told me, “Kha le, mummy aur banayegi hogi.” Eat it, my mother must have made more.

She was one of those girls who did not giggle before sharing her opinions. She did not look like she had a boyfriend. But she did. The tallest guy in class. A guy who was confident that he would get into engineering school because he went to the right coaching.

I was living in an apartment by myself. I had told my dad that I would be bullied to death in a hostel.

I was femme and from the Northeast. It would be misleading to say that I was all alone. Furthermore, I was also scared of the stove and did not know how to cook. It was out of pity that she shared her food.

When the boyfriend saw her share food he was riled up. On other occasions, he had been great to me. He like other boys would mock me through salutations but only rarely. It affected me less and sometimes even gave me levity. But this time around he began throwing slurs at me, staggering like a drunkard in the movies.

I didn’t know what to do. I was hungry because I hadn’t eaten breakfast and I hadn’t had enough lunch. But I also did not want to face the athletic guy who stood four inches taller than me. So, I returned the half-eaten bhindi.

“Why are you annoying him?” she roared at him.

With that, both became meteors of insults. Spit flew occasionally. Afterwards I said to her, “He was just jealous, you know.” I patted her head. My understanding of heterosexuality remained within images I got from NatGeo. We are only animals trying to pee around the periphery of our territory. We want to keep what is ours to ourselves. As a gay man, I understand that we not only mark territories but also, unlike animals, we pee on people and ourselves too.

“He is a douchebag. He does not know how to talk to others,” she said.

It shocked me that she knew him and saw through him. She saw through what was so apparent to me was love. She knew that his inability to dignify me meant something. That the reverberations of his actions would soon fall on her.

I wish I could say she loved me. She didn’t, the way I had defined love. But she did love me, in that she loved herself. She extended me the kindness she understood she would need someday and hoped that someone would fight for her too when she was weary.

There was something about being that young, being in a square box with other hormonal folks, and wanting to connect with others that made love less abstract. It was a type of connection that fostered growth. Growth that enabled us to see not our differences but togetherness. If love can’t do that, what is even its point?

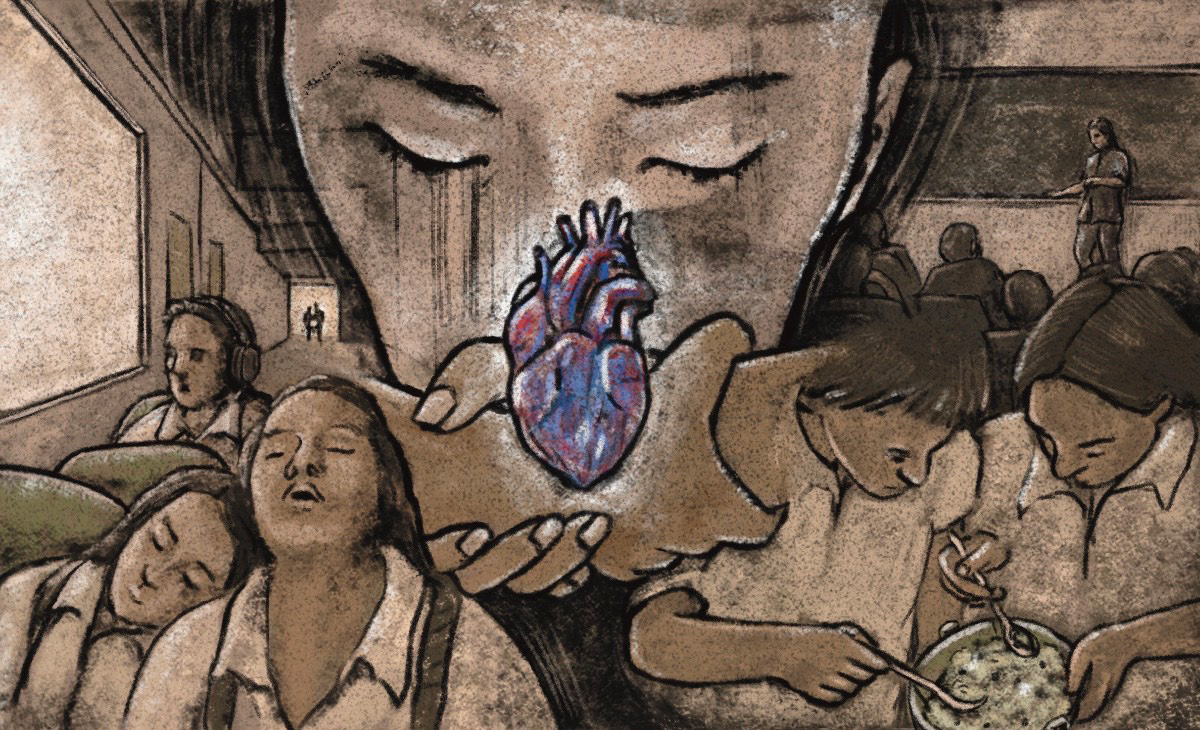

bell hooks, in her book Teaching to Transgress, questions the premise that the classroom just belongs to the mind. Our bodies also belong in that space. This might seem very obvious as our bodies literally take up physical space as we sit in class. hooks tries to hint at something more potent; how we have been asked to leave our bodies out when we enter the classroom. Instead of addressing the ways in which our bodies grow and differ, we are asked to bring less attention to it and repress its very capacity to take up space.

The uniform here is a representative of that mission to erase the body.

Another way in which this is done is by surveilling issues around desire. Bodies enable desire. They also mark what we desire and when we desire. The very muting of the body is a symptom of a society that grapples with the anxiety of a body’s capacity. This, in turn, leads to very confusing ideas around gender and sexuality, which often become social norms.

Ironically, in order to alter this, we should recognise the space our body takes. We need to validate our bodies and our desires. hooks would argue that the classroom is the space where this process starts. For her, “Knowledge and critical thought done in the classroom should inform our habits of being and ways of living outside the classroom.” Since the world outside so quickly seeps into the classroom, it is myopic not to engage with the discourse of desire critically.

On my second last day of class, I taught my middle-school students ways to find a character’s voice. I asked them to give their character a peculiar interest, object or obsession. They found this rather opaque so I asked them to tell me about things they don’t like in potential crushes.

In a flurry, the room burst into hands waving their romantic red flags.

One student told me very peculiar three things. I was fascinated that all three red flags were aspects of that student. A great teaching opportunity arose. I told the class that the line between us and them was always thin. While telling them this, I occurred to me how so much of the focus on who we desire falls onto the object of our attention. When truly the thing that we most want to rejoice, celebrate and accept was ourselves. And the classroom should be a space to believe that we can love ourselves. That is what I asked the class to look for.