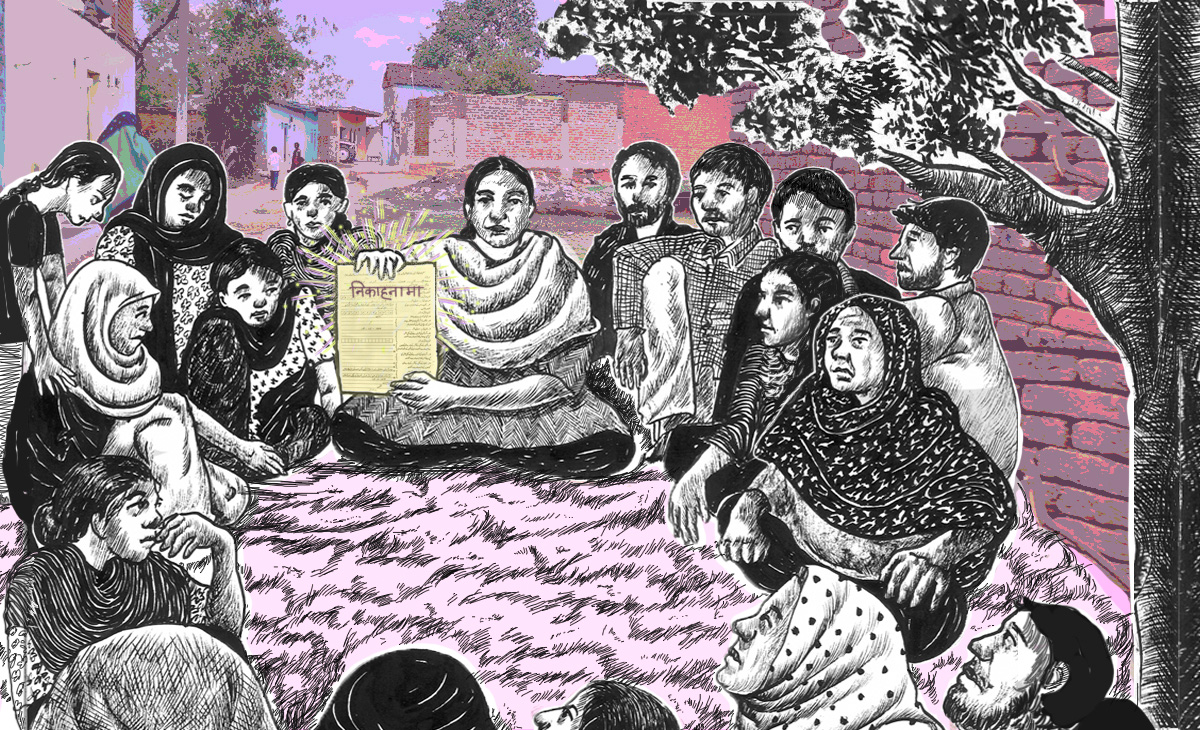

Marriage is a contract, as much as it is a ceremony. Drawing from her own life and marriage, a case worker writes about the nikahnama as a contract, the terms of which are seldom explained to women by maulvis. Celebrations and revelry provide cover to the fact that a very nominal amount of mehr gets negotiated and written into the contract. The caseworker analyses the nikahnama as being a safety net for women, giving them greater bargaining power. Yet silence or absence within this contract leaves them vulnerable in their marriages – both economically and emotionally.

What gets hidden in nikahnamas? Who gatekeeps the knowledge in the contract and why? A caseworker from a women’s collective Vanangana, in Banda reads and writes between the lines.

The Third Eye worked with 12 caseworkers in rural and small town Uttar Pradesh, and through a process that included immersive writing, theatre-based pedagogies and year long workshops, the caseworkers became the lexicographers of The Caseworkers’ Dictionary of Violence.

I live in Banda city in Uttar Pradesh and belong to a Muslim family. For a long time, I lived in a joint family. Our family had 16 girls; some older than me, and some younger. All of them got married in the Muslim tradition, through a nikah ceremony.

According to Muslim practice, the nikah or marriage is a samjhauta. With the agreement of both parties, the nikahnama, a contract, is drawn up on paper and signed. But my sisters and I were never sure whether Muslim marriage was really a contract. Our mind was filled with questions. Why is the nikahnama always written by the qazi? And why is it preserved with such care?

Presently, my home consists of four sisters and a brother. Everyone’s nikah papers, till date, have been kept with great care. We have noticed that there are no terms mentioned in any of these nikahnamas, except one—a reference to the mehr (an agreed sum of money and other items paid by the groom to the bride as agreed in the contract), and signatures of the witnesses to testify that the nikah had taken place. There are no other terms in the contract.

Even today, I am unable to comprehend whether the mehr mentioned in a contract at a nikah is ajjal (payment made to the bride at the time of the nikah) or muajjal (amount paid at any point in her lifetime). Why is it unclear and why do qazis not clarify this to girls at the time of the nikah? What kind of a samjhauta is this, after all, where a woman who is a part of the contract does not understand the meaning of the words written in the marriage contract, and the kind of impact they will have on her life? Why are these things kept hidden from her?

And as for the people who conduct these weddings—why do they not talk about adding more terms to the contract? Are they really unaware, or do they ignore the scope of the nikahnama on purpose?

I am told that a nikahnama is like this because a wedding should not be the occasion for any kind of dispute or argument, even if it ultimately stands to ruin the life of a girl. But there are often disagreements at weddings—around mehr. People try to bring down the sum of the mehr to as small an amount as possible. Maulvis tell us that the mehr affixed for Bibi Fatima, our Prophet’s daughter, amounted to Rs. 786. Looking at today’s economic situation, the advice of the maulvis is to affix the mehr at Rs. 10,000 to 15,000. It is surprising that even educated maulvis propagate this estimate. What they never say is that in the time of Fatima, the mehr of a woman was affixed to the amount of gold equivalent to the height of seven camels!

The qazis responsible for conducting a wedding focus only on those limited conditions in the marriage contract that are imperative for the conduct of the wedding. They never talk about adding more terms and conditions to the contract. It is clear that even the men who are the so-called custodians of the Muslim faith, do not want to provide adequate information on this issue. Even as I might refer to marriage as a contract today, at the time of my own nikah, I didn’t know it to be a contract or that I could change its terms. At that time, we placed great importance to the format provided by the qazi.

It was only later, after getting out of the house and years of working for NGOs that I finally understood what the real terms of a Muslim marriage are. It was at a meeting of the Bebaak Collective that we were informed about the Muslim Personal Law.

At last I understood that if used wisely, the nikahnama can go a long way in strengthening the position of married women.

Let me give you an example.

Suppose, while preparing the nikahnama, a term is added which says that divorce would take place only with the talaaq – e – mubaarat (mutual agreement) of both the parties, and that people from both the sides must be present to witness the mutual dialogue in order to fulfil the divorce proceedings. With this term in place, the woman no longer has to nurse the fear that her husband can divorce her anytime. Also, in the event of a separation, divorce would be conducted with the mutual consent of both husband and wife.

Ever since I understood that Muslim marriage is a contract, I have tried to learn about Muslim Personal Law in more detail. I decided that it is essential to go to village after village and educate women and girls about it. Men are often a part of these conversations that I have with women on this subject. After listening to these discussions, the men sitting there admit that they have never thought about the issue so deeply, and that the elders at home, or even the qazi, never discussed the matter with them. My experience with this work tells me that this issue is not publicised enough.

I do believe that nikah is that joyous ceremony which binds two people in marriage. Terms and conditions in the marriage contract tend to get sidelined amidst wedding traditions and functions. Women are informed, if at all, of a few rights and entitlements in a careless, cursory manner. And we women are so mesmerised by the wedding celebrations that we never understand the seriousness of this matter. Of course, in many cases, the girls and women of the family have no say in matters of their own marriage. All the decisions are taken by the men and elders of the family. The girls are content in the knowledge that whatever the family decides for them would be the best for them. But they do not know that perhaps, even the decision-makers are not fully aware of the true terms of a nikah.

I say this with great conviction and my own experience, that today whether the bride belongs to a poor family or a rich one, there are no additional terms and conditions added to their nikahnama. In both cases, the nikahnama is essentially the same. The supposed mutual agreement of the parties to the nikahnama is a mere show. No one’s terms are included in the contract. In any other kind of dispute in the family, the terms would be written down, read out and explained. But in the name of celebrating the wedding, a girl’s life is completely ignored. Why has it been this way and how much longer will this go on?

Translated from Hindi by Pakhi Pande with inputs from the TTE Team.