The Mind Map accompanies our Travel Log. The third Eye’s Travel Log Programme mentored 13 writers and image-makers from across India’s bylanes to reimagine the idea of the city through a feminist lens.

An artist worked with a fellow to visualise their town, village or city, a ‘map’ of the spaces they actually live in; a combination of their mental, emotional, spiritual and physical landscapes to help us imagine the ‘city’ subjectively.

Abhishek Anicca is a writer, poet and performer based in Darbhanga, Bihar. He identifies as a person with disability and chronic illness, which shapes his creative endeavours.

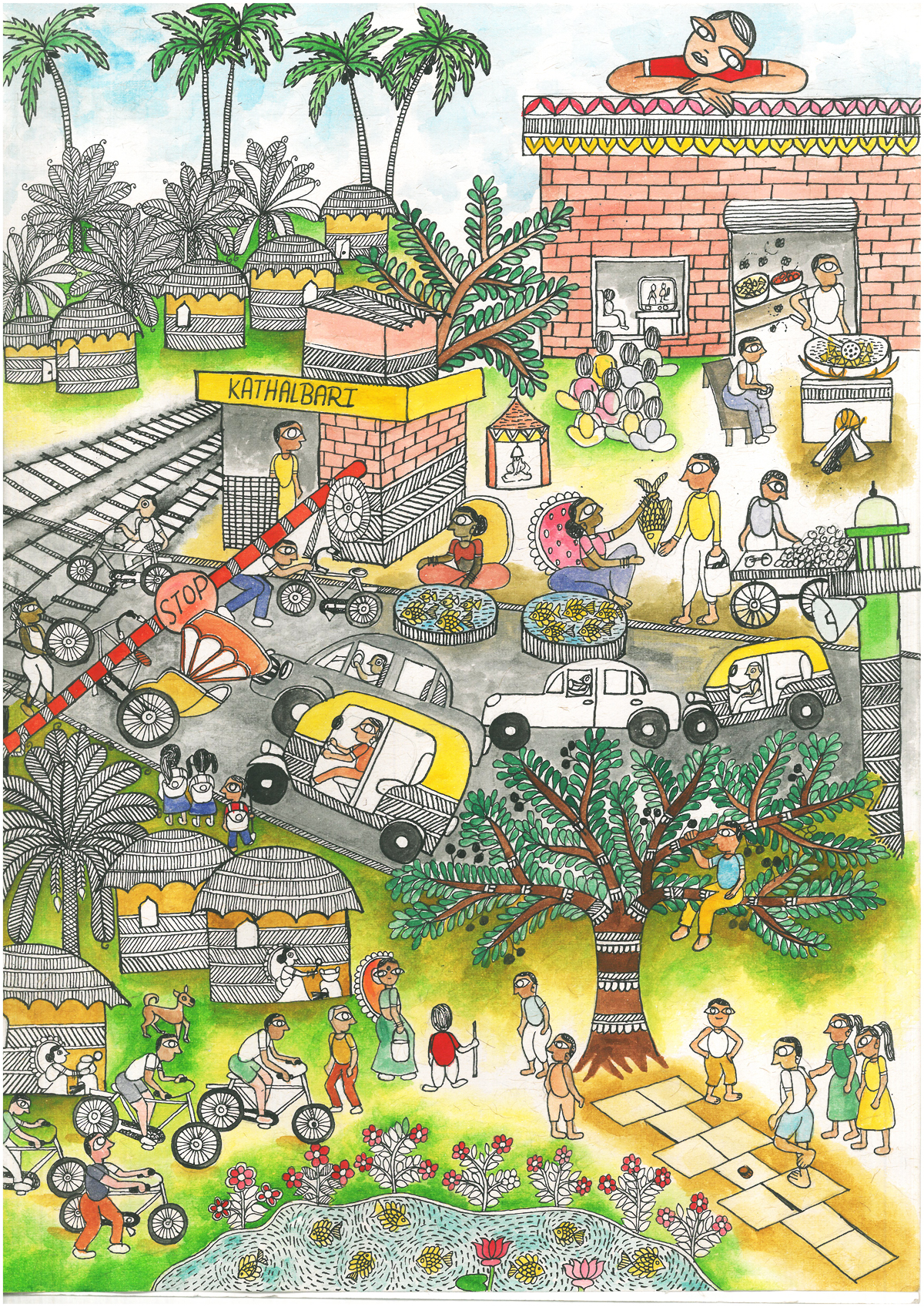

Anicca’s Mind Map is imagined by Malvika Raj, a Madhubani artist based in Patna, Bihar, whose work engages with Dalit history, identity and their intersections with Buddhism.

Presenting our first Mind Map of the series, with a free verse exchange between the two Bihar natives.

Malvika: What did you think of the first meeting both of us had? What was it that helped us connect?

Abhishek: I had seen your art before, so I already felt connected. I love your art. I believe we are from very similar cities and have had similar experiences growing up — growing up in small towns in the 1980s and ’90s was pretty much the same everywhere. We both know the vibe of Patna from that decade; in fact you’re the only one I can talk to about Maurya Lok!

Malvika (laughs): I don’t think if we mention Maurya Lok to someone who has only lived in Patna in the last decade, they would get it…

Abhishek: Precisely. Now that fancier shopping complexes have sprung up, people wouldn’t understand why Maurya Lok used to be a shopping hub in our times. It’s only we who have grown up in certain contexts, in a certain era, who would get these reference points.

I think you’ve visualised [my essay] Hopscotch very well. The imagery feels very familiar, almost like you’ve had front-row tickets to decades of my visual memory.

Malvika: While I know both of us had different experiences because of our particular subjectivities,

your experience as a man with disabilities growing up in small-town Bihar, really resonated with me as a woman growing up in small-town Bihar.

We as objects of scrutiny, piquing everyone’s curiosity, constantly under the prying gaze of passers by. Knowing when to expect it and learning how to dodge it.

Abhishek: Ah, scrutiny! One can never escape it in Darbhanga or Patna, no? Whether it was (is) my fat, disabled body navigating through the bylanes or my cousin sisters being stared at for wearing skirts in Maurya Lok, our hometown never felt like home, it was only where our home was.

I noticed how you situated me right at the circumference in the Mind Map – I feel like I am watching and being watched simultaneously; subverting and also embodying the panopticon.

Malvika: I couldn’t draw you in the middle of the chaos. How could I, when we both know we are trying to escape it, and yet feel stuck in it, knowing things wouldn’t change. We accept our realities of 6 pm curfew and traumatic public outings.

Abhishek: It has become even more suffocating over the years – the helplessness of being stuck in this small city is compounded by my health issues, which nullify all my plans of escaping Darbhanga even before they materialise. The only good, core memories that I carry from this place are the ones I associate with people, about which I write in the piece as well.

But in addition to trauma, small towns also relegate you to a certain occupation, and education. Times may be changing now but I don’t think a lot of young people can even dream of pursuing a career and education in the arts. Social mobility is seen through engineering and commerce. Which is why your art stuns me, Malvika! You must have braved so many odds growing up in Patna to be able to pursue art and excel in it the way you do today.

Malvika (laughs): Quite contrary to my artistic desires, my parents’ aspirations were strongly rooted in their daughter becoming a doctor. It took a fair amount of negotiations and time for them to understand my inclination towards art and design. I am still not sure if my family exactly knows what I do.

But isn’t that where the most interesting stories take shape? How do people like us negotiate with the realities of our small towns and kasbahs and experiment with what they allow us to do and what they don’t?

It is in this space of negotiating; fighting silent battles, without the anonymity and framework of opportunity provided by big cities, that the greatest poetry and art emerge. I’d like to take the liberty of attributing the coming together of the Mind Map to this!

Abhishek: This whole idea of negotiation is very interesting which immediately takes me to the ghoomti (railway crossing), which you have drawn in the Mind Map. Anyone who has commuted to school in a rickshaw or a buggy would relate to this jammed railway crossing. There would only be two railway crossings, mainly because railway stations were constructed right in the middle of the city.

I loved how you portrayed people crossing the ghoomti, trying to manoeuvre their autos under the closed jaali – a whole exercise in (im)patience, defying time and making your way through the traps, all of which small towns train you to do very well.

Another element from the artwork that also stayed with me the most is the circular nature in which the whole city is set. I don’t say it outright but I often feel like I am stuck in a circle with my illness and disability. The circularity, thus, is very representational to me – both of rut and hope, which you have again captured beautifully.

My positioning on the circumference of this ‘life’ as it goes on, at a certain distance, sitting on the terrace, staring into nothingness…feels truthful.

I would like to carry this image of me and want to believe that I am not just looking at the past but also the future.

I don’t necessarily plan the future because it’s so unreliable but I do hold a certain sense of hope. I’d like to hold onto that. Your visual imagination holds space for hope and it feels like someone has narrated my exact story, my exact words through art.

Malvika: I am very happy to hear that, Abhishek. Even since I learned how to paint, my focus was to develop my craft as a means of storytelling and it feels like I have managed to do that through the Mind Map.

Abhishek: When you sent me the initial black-and-white draft, I was so excited. I showed it to my nani who absolutely loved it and I have plans of printing this out and hanging it on my wall. After all, these are images that won’t come back and remain only in our mind now. You’ve preserved memory and time in art.

Malvika: Memory is a tricky landscape for me because I am also shaped by my experience of facing extreme casteism in an all-girls school in Bihar. No one would share lunch with me at school and I wasn’t very good with numbers or languages. Art was my only refuge.

Abhishek: Schools do prepare you well for the violence one faces later on in life, especially if you are not upper-caste or able-bodied.

Malvika: Yes, this is why my childhood wasn’t ‘happening’ or enjoyable at all, and I don’t have much nostalgia. I don’t want to go back to that era. Hence, I have also tried to incorporate certain elements in the Mind Map from that interplay of distance – I don’t really want to relive my childhood in Bihar – and your memory of it.

Abhishek: The only reason I would perhaps want to go back to the past is because I am completely immobile in the present. My subconscious desires a physical manifestation of the times when I could play cricket. But apart from this, even I wouldn’t want to go back to my childhood.

Nostalgia is both – a privilege for those who have not lived in a broken place like Bihar and a way of coping with the subdued guilt of leaving behind your hometown and family.