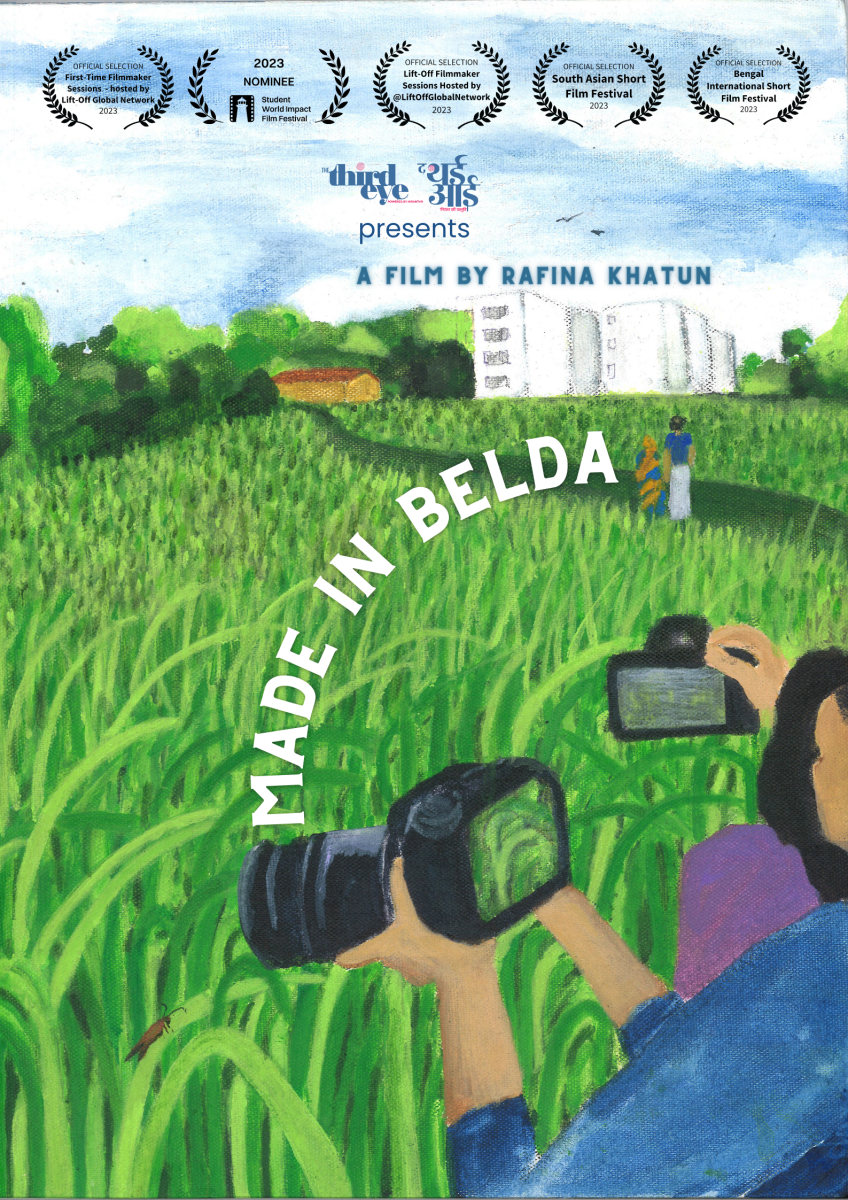

Rafina Khatun is a part of the Travel Log Programme with The Third Eye for its City Edition. The Travel Log programme mentored thirteen writers and image makers from across India’s bylanes, who reimagine the idea of the city through a feminist lens.

Rafina’s parents call her a free bird. What happens when this free bird goes back to her nest and investigates all that helped her ride the wind? Wearing the heavy hats of both filmmaker and daughter, Rafina asks tough questions to her parents amidst birthday cakes, cows, and abstract drawing books in this autobiographical documentation. In the process, she captures everyday moments of joy, right where it all began.

I felt really awkward when I finally realised that I will be shooting my family. When I said this to them, my mummy asked, “What will you shoot? What will you show? What do you want me to do?” I responded, “I don’t want you to do anything. You just be yourself. Do your work and I will do mine.” When we shoot outside, it’s actually easier because strangers politely agree to most of our requests. But our families can easily tell us: “Don’t do all this now. I am busy.” So, to record them was really difficult at times. Since the shooting went on for six months, everyone had time to get used to the camera and ignore me.

When I told Shivam and Shabani (The Third Eye Team) about my didi (Farha Khatun), who is an established documentary filmmaker and the first girl in my village—Belda, in West Bengal—to pursue higher education and that too outside the village, the idea for this film emerged. We decided that I can interview and shoot my family members and through them, narrate the story of Belda.

When I started, I didn’t know how it would come together because it was my first film. I was also editing it simultaneously. I’d shoot for one or two days, come back and edit, and then go out again to shoot. Now that I am watching the film, it’s looking quite nice. I hadn’t expected it to look this good. It seems crisp and the story I wanted to show is coming out well.

A couple of things also changed when the camera came into the picture. For example, my mummy is actually quite vocal. She has held this entire family together and she is the head of our family. It is because of her that the house is still standing. But if you watch the film, she does not behave like that. It is not because she is camera shy—you can see her asking my papa to sit properly. The way she talks on an everyday basis cannot be seen in the film. She would much rather direct things behind the camera.

My papa is, as usual, really chill with everything. He is very used to this attention or the gaze of the camera, because he has been a sports-person all his life. Similarly, my didi is also used to it. My bhabhi (sister-in-law) is really shy. When it was just the two of us chatting, the conversation would go smoothly. This also had a lot to do with the site being my home as I was completely comfortable moving around the entire space. Eventually, the film has captured everyone, more or less.

Towards the end of the film, I ask my parents why they didn’t allow my didi to become a journalist. This was a difficult one, not because I didn’t know the answer, but because I didn’t know if they would be open about it in front of the camera. All I knew was that they wouldn’t scold me for asking it. But, I still didn’t know how they would react. I guessed that there would be some silence and somberness after that interview and that is why I asked the tough questions at the end. So that even if someone became angry and refused to appear in front of the camera again, that would be okay. Even I felt a little bad asking that question on camera because I didn’t want my parents to be portrayed in a bad light. I know that my family is really good and simple, but what would happen if the film fails to show that? To ask this question was also important because, without taking any of the freedoms and choices we have been given for granted, there are certain choices which have also been taken away from us. I certainly feel confident after having shot that.

My face does not appear at any point in the film, but that’s okay because it’s me who is witnessing the entire story unfold in the present.

I am not in the film, but the entire film is through my eyes. That’s where my presence lies.

In the end, all the stories are connected to me. All these people struggled so that I wouldn’t have to. When all is said and done, it all comes down to me, the “free bird” (aazaad parindi as mentioned in the film).

For me, this film is not a “film” because it is also my own story. I am working on my second film now but this one will always remain very special for me. What is left now is for my family to see it. The next time I am there, I plan to do a special screening for everyone in my village.