This is a non-exhaustive list of resources for anyone interested in understanding the various debates and trajectories of the sex work movement in India. In case you want any resource to be added to the primer, please write to us at [email protected] with recommendations.

On May 19, 2022, a bench of the Supreme Court of India issued a directive recognising sex work as a profession, wherein the practitioners of sex work shouldn’t be penalised, harassed, incarcerated or punished if they are consenting adults. The directive further established that sex workers should be offered equal protection like any other worker under law, the police shouldn’t abuse them, and prohibited media from circulating their pictures during ‘rescue and raid’ operations (the legality of which is debatable itself). Sex worker groups, including the National Network of Sex Workers (NNSW) in India, welcomed the directive and called it “a step towards decriminalising sex work and sex workers”.

As we decode this ruling and debate the actual, on-ground implementations and ramifications of it alike, The Third Eye is putting together resources to initiate a deeper understanding of the theoretical, social and spatial movements shaping the debates around sex work. What is the history of the criminalisation of sex work? What are the varying positions around sex work; what encompasses the politics of various sex worker groups? What role does colonialism play? How does the specificity of caste in our context open up ways to rethink feminist ideas about consent, embodied labour and the law vis-à-vis sex work?

Recognising sex work as work: A history

The usage of the term ‘sex work’ itself has a history within the feminist movement of various contentions and negotiations amongst different ideological strands. One strand believes that all of ‘prostitution’ is illegal and constitutes as sexual violence against women. Proponents of this point of view, also known as abolitionists, believe that recognition of prostitution as work, especially as voluntary, consensual work would negate the exploitative and undignified conditions surrounding the sex trade. The other strand, which seeks to decriminalise and recognise prostitution as sex work, believes that it is important to bring sexual labour into the framework of right to work. They argue that in order to imagine feminist, labour-organising and interventions in the sex trade, it would need to be recognised as work, to accord the sex worker the dignity as well as equal protection under law. In their opinion, complete abolition of sex work is unrealistic, and would lead to a loss of livelihood. In her article, Sex Work and the Global Economy, Svati. P. Shah reflects on her own experience working as part of an HIV/AIDS Project in Kamathipura, the largest red-light district in India. She breaks down the debate very succinctly and discusses how “the shift from ‘prostitution’ to ‘sex work’ represents an explicit attempt to bring prostitution into the sphere of labour.”

On January 28, 1995, women sex workers from Sangli, who collectivised in 1997 as

Veshya Anyay Mukti Parishad (VAMP), read out a very powerful statement at the Speaking Tree, Womenspeak: Asia-Pacific Public Hearing on Crimes Against Women, which further opened up the debate on recognition of prostitution as ‘work’ or ‘profession’, and also added a nuanced reading of the nature of their work—as an economic activity. A part of the statement read: “We disagree with the formulation that prostitution is a profession. We make a distinction between profession (vyavasay) and occupation/business (dhandha). For instance, if we are presently occupied by making money out of sex, then that is our occupation for a short span of time. The nature of the business itself is time-bound. Therefore, by using the term profession, we are necessarily being pushed into a category for a lifetime. We are women who are practicing this time-bound business of prostitution for a short and specific period in our lives. Please remember that when we are not making money out of sex, we are engaged in other income-generating activities.”

Choice, agency, or the lack of it

Similarly, at the first National Sex Workers Conference held at Calcutta in 1997, the Durbar Mahila Samanwaya Committee (DMSC) released a manifesto answering some of the questions that surrounded the oldest profession in the world. What is the sex workers’ movement all about? What is the history of sexual morality? Do men and women have equal claims to sexuality? One of the most pertinent questions perhaps, that they addressed was this: why do women come to prostitution? “Women take up prostitution for the same reason as they may take up any other livelihood option available to them. Our stories are not fundamentally different from the labourer from Bihar who pulls a rickshaw in Calcutta, or the worker from Calcutta who works part time in a factory in Bombay … But when do most of us women have access to choice within or outside the family? Do we become casual domestic labourer willingly? Do we have a choice about who we want to marry and when? The choice is rarely real for most women, particularly poor women.”

Shohini Ghosh’s acclaimed documentary Tales of the Night Fairies is a must watch to see how the DMSC movement and the Sonagachi utterance transformed how we see sex work and sex worker’s choice and autonomy.

However, Swati Ghosh offers a feminist rereading of DMSC’s manifesto by critiquing the narrow gender positionality of it. She says, that apart from a mere mention of “capitalist patriarchy”, there is little class analysis that is offered to think of women’s subjugation that forces them into sex work. However, she maintains that the manifesto opened up an entire new and nuanced world of morality and sexuality frameworks that were missing in the women’s movement for sex workers before. Infact, DMSC’s manifesto affiliated itself with LGBTQIA+ rights at a time when no feminist organisation even wanted to utter those alphabets.

A good resource to unpack the frequently used terms of ‘choice’ and ‘agency’ in the sex work debate is this extract from Nivedita Menon’s chapter, Victims or Agents, part of her seminal book, Seeing Like a Feminist. This chapter theoretically frames the understanding of choice in the labour market, and summarises the historical trajectory of the position on sex work from various schools of political thought—Marxist, Ambedkarite, Socialist, etc. It also further builds on the question of commodification of women’s bodies and what is embodied labour by going into debates of surrogacy. In addition, it conceptualises both the abolitionist and non-abolitionist views on sex work (and, subsequently, trafficking) and brings in questions of borders, states and nationalism to further interrogate it, thus opening up different frameworks to look at sex work, migration and cities.

Although for a full reading on how ‘choice’ depends on structural histories, especially the intersection of sexuality and structures, the deeply personal essay by a Latina sex worker, A Socialist, Feminist, and Transgender Analysis of “Sex Work”, makes some tough points. “The only real freedom in prostitution is the freedom for bourgeois men to access the bodies of proletarian women.” In this essay, a survivor of the sex trade argues for the abolishing of ‘prostitution/, along with the conditions that created it.

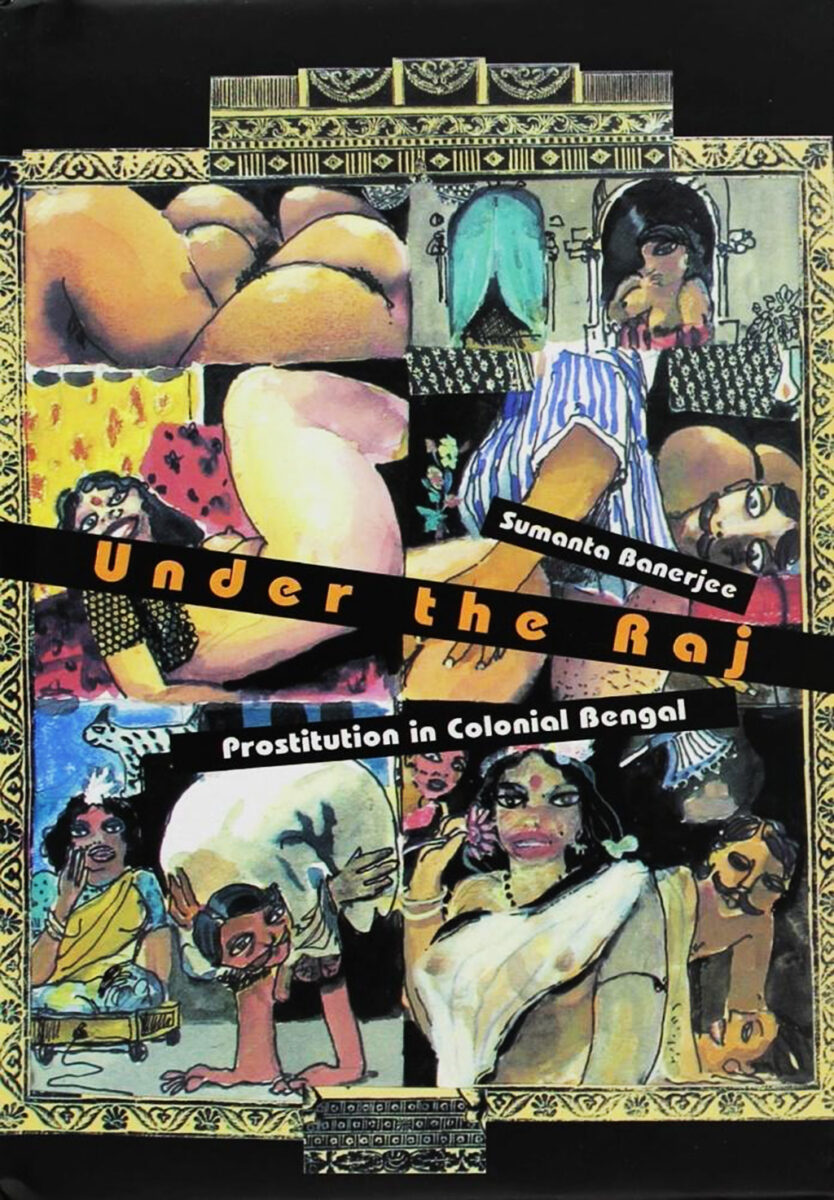

The role of the British

When we look at the sex work movement in India, we also look at specificities of colonialism and the caste structure, and how they have shaped historical as well as contemporary positions on sex work. How did colonial morality shape sex work—as an occupation and its spatiality? The British not only revamped the profession of prostitution to suit their own needs (and make it exclusive for their minions and soldiers) but they also brought in various Contagious Diseases ordinances, the burden and punishment of which was borne by the colonised sex workers. Sumanta Banerjee’s book, Under the Raj: Prostitution in Colonial Bengal, explores 19th century colonial Bengal and how sex work shaped it as a fast-growing trade—he looks at the responses of both—the colonial administration as well as the changing nature of social relations in the Bengali Bhadralok community towards this flourishing trade. What is particularly interesting in the book is the chapter, Voices from the Pit, wherein Banerjee traces the archives of sex workers—both oral and written—through half-decoded songs, letters and folklore to give a visual and cultural insight into the lives of the sex workers and the relations they forged. For example, here is a lyric that he analyses in the book: “Machh khabi to ilish. Nang dhorbi to pulish. (If you want to eat fish, choose hilsa. If you want to take a lover, choose a policeman). The insinuation is clear. A cop tastes better since he can protect the prostitute, who, in her turn, can also ensnare him in her net (like the hilsa) and fleece him to her advantage.”

Another site to turn to, to look at conflicting morality debates regarding sex work in the colonial period is the section, Female Space, from the chapter Space and Place ¬– The Marketplace Of Colonial Sex in Phillipa Levine’s book, Prostitution, Race and Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire. Levine looks at two female spaces, the zenana and the brothel—both on the opposite ends of the respectability spectrum but inviting a similar coloniser’s gaze—that of the ‘idle’ ‘exotic’ Indian woman living in a dingy space devoid of light and air.

Migration and cities

The Third Eye’s video essay, Sex [Work] and the City, narrated by Dr. Paromita Chakravarti, looks at the current pandemic as an echo from the past, when the British passed the Contagious Diseases Act of the 1860s, which gave the state the power to regulate ‘common prostitutes’, in order to reduce the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases within the British army and navy.

Similarly, the book, Sex, Work and Migration in the City of Mumbai by Swati P. Shah, begins by exploring the question of sex work and ends with exploring the city—it maps how migrant women navigate and negotiate survival in the backdrop of the sex industry. Particularly relevant is Chapter 4, Red-Light Districts, Rescue, and Real Estate, focussing on two lines of enquiry: the first situating brothel-based sex work within the conceptual spaces of migration and economic informality; and the second analysing the decline of brothel-based sex work in south Mumbai vis-à-vis real-estate mafia, abolitionist NGOs, politicians, police, etc.

As we look at sex work within the framework of migration, Manjima Bhattacharya in her interview with The Third Eye breaks it down for us as to how the processes of globalisation and technology have also changed sexual commerce. She offers intriguing insights in how the internet has changed digital intimacy, a short minute before the advent of Tinder and similar apps against the backdrop of Mumbai. While OnlyFans has spread its wings outside of India, the mobile phone too has changed the nature of sexual commerce, especially post-Covid. Street-based sex workers now not only find clients and do business over their mobile phone, but also turn to it in times of distress whenever they are caught in a police raid and need help

The morality question

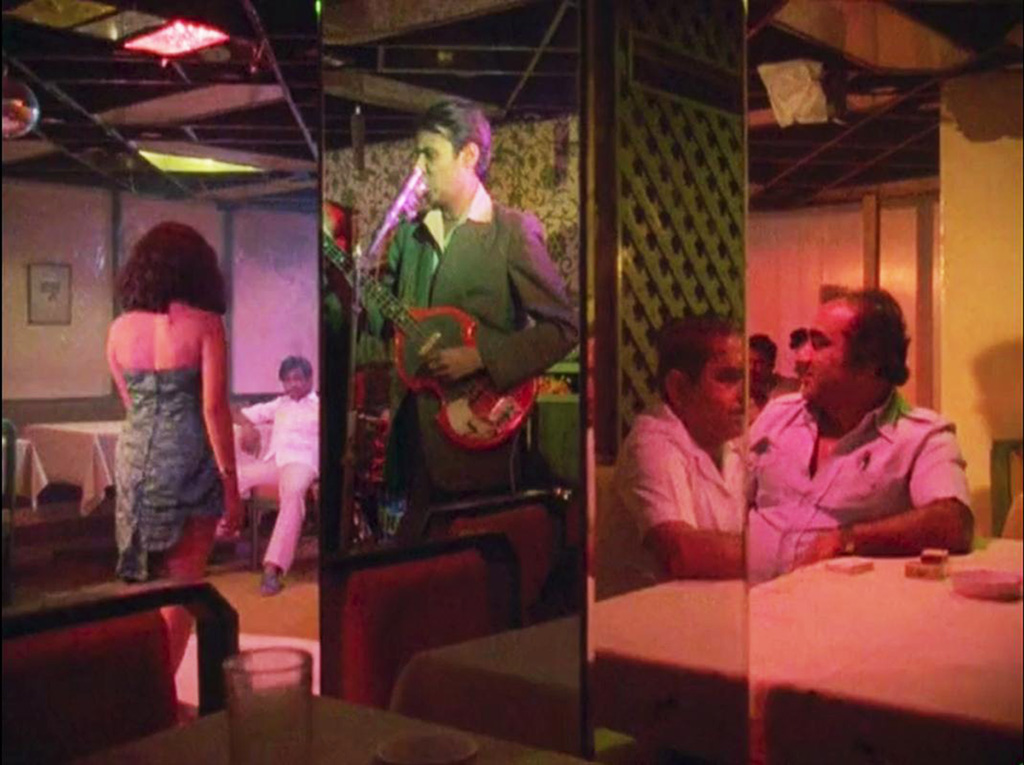

Morality debates have gained new cover but continue to plague the question of sex work in post-colonial India and impact social and spatial formations. Flavia Agnes’s piece, Hypocritical Morality: Mumbai’s Ban on Bar Dancers, was penned in Manushi in the aftermath of the ban on bar dancers in Mumbai in 2005. How did the alcohol trade lead to the setting up, proliferation and conversion of Punjabi and South Indian-owned dhabas and restaurants into dance bars in central and western Mumbai? Agnes also sociologically explores the trajectory of sex workers’ children from brothel-based sex trade in Kamathipura to non-brothel sex work in these dance bars, and thus delves into newer aspects of migration, labour and inter-generational occupational mobility. Mira Nair’s film, India Cabaret, was released at a time when the discourse around bar dancers as a profession, much like sex work, was marred with well-meaning moralising. India Cabaret does the incredible work of uncoupling the joy of hard-won independence from the shame such independence often comes with.

Debolina Dutta pens this award-winning paper, titled Of Sex Workers, Festivals and Rights: A Story of an Affirmative Sabotage, where she explores the often fraught relationship between sexuality and religion by looking at how the organisation of the Durga Pooja festival in Kolkata by sex workers is an act of resistance and reordering of power structures. “Sex workers do something that is more complex than resisting oppressive power structures. They authorize and practice the relationships they inhabit, differently. Indeed, they re-work and re-order their ties with institutions, such as the state, and with other people, in order to experience life on their own terms.”

Sex work and its cultural roots

Another useful resource to explore is this reader, Prostitution and Beyond – An Analysis of Sex Work in India (edited by Rohini Sahni, V. Kalyan Shankar Hemant Apte). Section 2 of this book, titled ‘Through the Kaleidoscope of Time: Changing Forms and Emerging Realities’, looks at sex work in India and maps its historical trajectory in relation to different communities and demographics across regions. It includes the study of the Devadasi tradition and institutionalised prostitution, and the history of Jogins in Andhra Pradesh with the help of case studies. It further builds on discussing distinct historical sex work practices with a case study of the sexual behaviour of the Nat women in Rajasthan engaged in community-based sex work. It also contrasts urban and non-urban forms of sex work with ethnographic accounts of brothel-based sex trade in Dharwad and the non-brothel-based sex work practised by ‘call girls’.

Shailaja Paik’s Mangala Bansode and the Social Life of Tamasha: Caste, Sexuality, and

Discrimination in Modern Maharashtra traces the oral history of Mangalatai Bansode, a rare and powerful Dalit professional Tamasgir (Tamasha performer) and examines the ways she repeatedly performed the ‘obscene’ and the ‘erotic’. She unpacks “unexplored potentials and problems of intimate and interlocking relations between a Dalit woman artist’s ‘deviant’ sexuality, labor, and struggle for survival.”

The caste question

The feminist movement in India has inadequately dealt with the question of caste, more so when it is the domain of sex work. What is the link between caste, labour and sexuality? How can feminist thinking on caste and sexual labour link research with activism and practice, in conjunction with different lived experiences of caste? Drawing from her activism and experiences as a member in Forum Against Oppression of Women in Mumbai, Meena Gopal pens Caste, Sexuality and Labour: The Troubled Connection looking at similar questions. Thus, sex work in India is not merely an organisation of gender and labour relations, but also of caste, from pre-colonial times. Dalit women in sex work experience sexualised division of labour, which takes the form of ritualised sex slavery in certain communities. In 2007, Anti-Slavery International published a study titled Women in Ritual Slavery. It documented the practice of ritual sexual slavery or forced religious ‘marriage’ in Devadasis and Jogins in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. The study found that 93% of Devadasis were from Scheduled Castes (Dalits) and 7% from Scheduled Tribes (indigenous) in India.

Priyadarshini Vijaisri’s paper, Contending Identities: Sacred Prostitution and Reform in Colonial South India, locates the multiple patterns of South Indian temple prostitution in a pluralistic culture and also explores the different identities and sub-cultures within. It asks the pertinent question: “Can any religious tradition—especially one that is part of an extremely hierarchical and patriarchal temple structure—be studied in isolation to the all-pervading influence of caste as an ideology of power?”

Another important resource is this Caravan report, titled A Hard Place – A Dalit community struggles to break away from sex work, by Urmi Bhattacheryya. It is an investigative, interview-based piece on how 1,500 girls from the Bacchada settlement identified as a Scheduled Caste in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan enter the sex trade every year. “As the COVID-19 lockdown dragged on, the sex trade along the highway ground to a halt. ‘I don’t go out anymore,’ a 26-year-old woman with two young sons told me. ‘I know no one’s coming.’ But the break in the trade brought desperation, not relief. ‘What can I do?’ she said. We’ll have to eat somehow.’”

Sex work and the law

The law as a framework has been of utmost contention in the sex worker movement. On the one hand, it is used to punish, police and incarcerate the sex worker, and on the other, under the grab of ‘protectionist’ virtues, it is also used to conflate adult consensual sex work as trafficking, and propagated the raid-rescue approach.

The politics of pandemic control and surveillance has also, in turn, reframed sex work debates. In Chapter 4, ‘Not on the Lord’s Agenda: The Traveling Sex Workers of Tirupati’, from her book Dangerous Sex, Invisible Labor: Sex Work and the Law in India, Prabha Kotiswaran assesses the redistributive potential of the law in the context of sex work by analysing the different effects criminalisation, partial and complete decriminalisation, and legalisation would have on the political economy of sex workers. Her in-depth fieldwork among sex workers in Tirupati, a temple town in southern India, also challenges the fetishised stereotype of a brothel-based sex slave in a Third World metropolitan city.

While filming his documentary The Return, Roop Sen interviewed a young woman from Bangladesh who had been trafficked into sex work in India and was subsequently rescued and placed in a shelter home run by an anti-trafficking nonprofit in Maharashtra. He asked her, “Between your home in Bangladesh [where she felt deprived], the brothel in Pune [where she felt violated], and the shelter home [where she was at the time], which place would you say was the best?” She replied, “All three were good. All of them demand subservience and obedience, and if you follow the rules, you get rewarded. And if you break the rules, you get punished.” He writes more about the “heroism-induced” narrative around rescuing sex workers in this piece.

As we question if the sex worker will ever be equal within the paradigm of law, Nandita Sharma’s 2003 book, Travel Agency: A Critique of Anti Trafficking Campaigns, goes beyond the debate on what is ‘work’ to situate the critique of anti-trafficking campaigns within what we understand by a nation-state. Are our anti-trafficking campaigns subsumed within a restricted understanding of cities and borders and ownership of space? Does our understanding of sex workers as migrants draw from/build on rationales that also supplement regressive migration policies? How can our reimagination of the sex worker as a migrant with limited agency contribute to a more transformative politics—that of mobility—staying and leaving in a self-determined manner?

Sex worker groups have increasingly voiced their concerns against the (im)morality of anti-trafficking campaigns. Penned by representatives of sex worker collectives Centre for Advocacy on Stigma and Marginalisation (CASAM), VAMP and SANGRAM (Sampada Grameen Mahila Sanstha), this article discusses the experiences of sex workers picked up during raid and rescue operations, who reveal that “such a strategy rarely addresses the issue of trafficking, instead results in large-scale human rights violations, and, in fact, increases vulnerabilities such as falling into debt bondage and other exploitative practices.” As Nalini Jameela suggests in her autobiography, often women who are accused of indulging in the ‘immoral’ practice of sex work, are the same people who compelled them into sex work.

While sex worker groups around the world uphold and welcome the Supreme Court directive in India, it is still a long road ahead of collectivisation and grappling with historical, social and political relations and structures. Rakhi, one of the leaders of the trans community, [in Kolkata] says in the aftermath of the judgment, “These people make promises just for votes. Our lives haven’t changed at all.”