M, a 37-year-old media practitioner based in New Delhi, writes in the survey on sexual fantasies mentioned in Part I of The Psyche Series:

“I recently found myself thinking a lot about making love in an outdoor space. My boyfriend introduced me to the pleasures of doing it on terraces and balconies, where people look at you without really knowing what’s happening. They suspect, but they don’t know. I think I want to take it further.”

M identifies herself as “the cliched strong, independent woman”. She writes about a fantasy that she feels addresses everything she is scared of in real life — confrontation and people seeing her as ‘loose’.

“[…] which is something I had people say to me throughout my very sexual adolescence and early 20s. I started covering my body as a reaction to friends who found my cleavage too ‘attention-seeking’ — if they only knew how much attention I’d get if my fantasy ever came true.”

Having had the fantasy for a long time, M doesn’t find it strange anymore. She hasn’t tried it out, at least not the public space part. As that strong, independent woman, M struggles to neatly delineate the fantasy from actual experience. She writes,

“The only thing that troubles me is that I'd like the sex to be forced. I don’t understand it and find myself very troubled that I find that hot.

I feel I need to understand something about myself — why would an act of violation be attractive to me?”

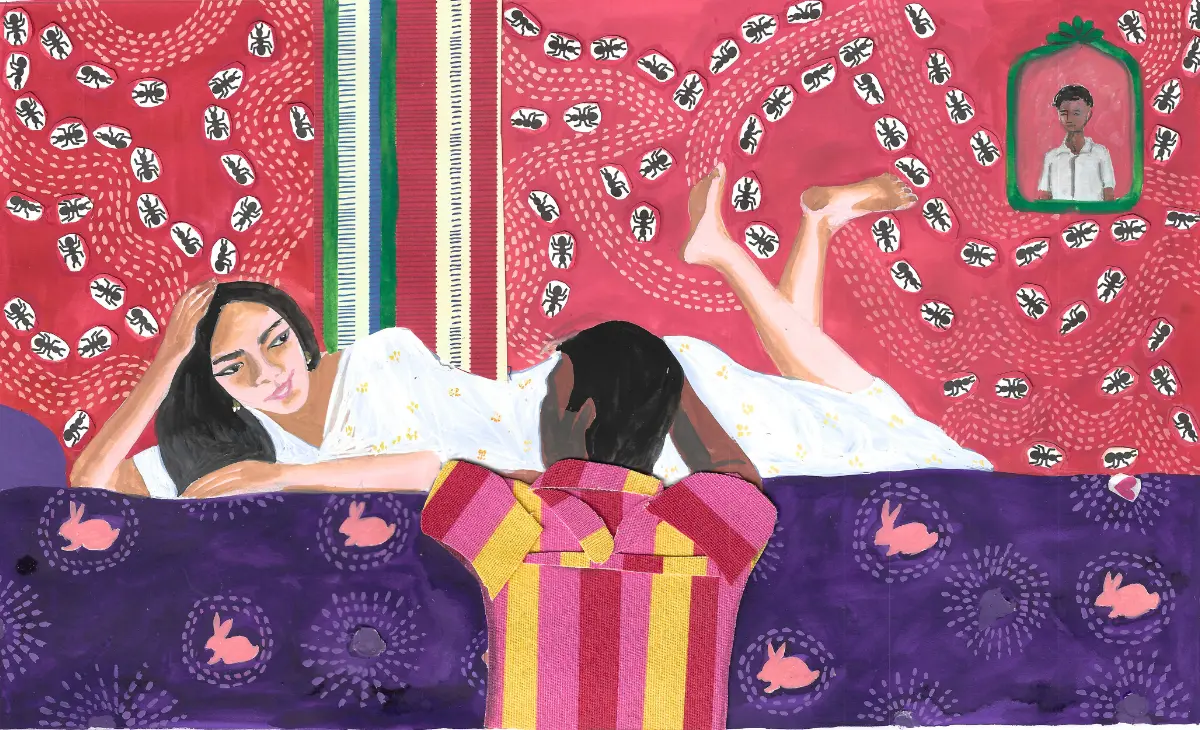

M’s sexual fantasy of forced sex on the terrace also involved two men and another woman; she did not express any inner conflict about this aspect of it. Although the outdoor setting, the involvement of more than two people and the inclusion of another woman all break sexual norms, she felt no qualms — and in fact a certain delight — in transgressing the norm that sex should be had only in private and with one person of the opposite sex.

About the almost exhibitionist aspect of having sex outdoors — with the acute awareness that people might see her — she was outright gleeful, especially about what the friends who judged her as being too attention-seeking would think if the fantasy did come true. The only aspect of her fantasy that M experienced inner conflict and bewilderment around was that she would like the sex to be forced.

In the survey I refer to in The Psyche Series, 20 of the 30 respondents felt conflicted about their fantasies. I would like to discuss two key aspects of the inner conflict expressed by these respondents. One relates to what I call the yummy-yucky nature of desires and the feelings around them, and the second relates to the interplay of prohibition and permission.

The Yummy–Yucky Nature of Our Desires

Georges Bataille would find this mix of seemingly contradictory emotions to be par for the course. Reflecting on the nature of desire, he asks, “Where would pleasure be if the anguish bound up with it did not lay bare its paradoxical aspect, if it were not felt as unbearable by the very person experiencing it?”1

Why are pleasant sensations and feelings accompanied by seemingly contrary sensations and feelings? Why do supposedly unpleasant sensations and feelings carry a psychic charge? Why do we feel what seems like excitement, or possibly pleasure, even as we suffer pain? It’s not only about sexual fantasies and our feelings about them. We know yummy-yucky-ness from every aspect of life in and around us — from longing and jealousy in love, to spicy food and horror films. To understand the hook, let’s turn to Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle.2

For much of his life as an analyst, Freud believed that humans operate according to the pleasure principle, that is, we pursue pleasure and that towards this goal we want “to reduce, to keep constant, or to remove internal tension”.3 However, towards the end of his career, Freud found that he was unable to reconcile the pleasure principle with what was repeatedly coming up in the experiences of his patients, as well as in family life around him.

Patients who had fought in World War II, wrote Freud, could not escape repeated traumatic dreams about the war. Other patients, too, kept going back to symptoms they found disturbing. Towards building a significant theory of attachment to symptoms, Freud describes, in almost comic ways, the behaviour of his clients during therapy.

His clients, wrote Freud, repeat “unwanted situations and painful emotions” and revive them during therapy with “the greatest ingenuity.”

They seek to “bring about the interruption of the treatment while it is still incomplete; they contrive once more to feel themselves scorned.”

Continuing his description of patients who were hell-bent on this pursuit, Freud writes that they “discover appropriate objects for their jealousy” and “produce a plan […] which turns out as a rule to be no less unreal”. He notes that despite knowing that “none of these things have produced pleasure in the past […] they are repeated, under pressure of a compulsion”.

Philosopher and writer Richard Boothby helps us further understand Freud’s work4 on why humans might behave in a way that seems to run so counter to what we think of as self-evident, commonsensical principles: the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain.

In early childhood, the infant is governed by powerful ‘drives’ of the body — to shit, pee, suck, taste at its will. The drives, including the anal and oral drives, allow entry and expulsion of objects and have “libidinal energies”.5 But they only hold sway until the emergence of a competing force: the ego. The growing child’s ego wants to limit the chaos of the drives by keeping them out or repressing them, in order to create and preserve a sense of unified self and a stable identity — a war of sorts, underway in the psyche!

This war, this clash between the ego and the drives, is marked by both pleasure and unpleasure. Resisting these drives is experienced by the ego as unpleasure, but whenever these drives are able to persist, the “libidinal energies erupt” and the energetic discharge is highly pleasurable. Dr Boothby — this is yummy-yuckyness, no? The eruption of libidinal energies in the unconscious is yummy and is experienced by the ego — which is working hard to repress — as something quite yucky.

Explaining why it is faulty to assume that only the pleasant is pleasurable, Dr Boothby writes, “The increase in tension that arises from the assertion of unbound energies can be productive of pleasure, indeed, of a far greater pleasure than that derived from bound energies.”6 Yet again, psychoanalysis offers us its ulta pulta (upside-down) wisdom: an increase in tension can be productive in terms of pleasure.

Bringing together Prohibition Eroticizes and Beyond the Pleasure Principle7 helps solve the mystery of why sexual fantasies can feel yummy-yucky. Transgression can be scary and yet, we are drawn to that which is taboo. The feeling of being turned on by something one considers to be against the rules (which may or may not be mainstream) is bound to be yummy-yucky.

Having made several references to Freud throughout my writing so far, I would like to conclude this fourth instalment of The Psyche Series with some reflections on the relationship between Freud and feminism.

I feel this is important also because the feminist suspicion around Freud often translates into feminist suspicion of psychoanalysis.

So, as much as what I’m going to say now is about Freud and feminism, it is also about feminism and psychoanalysis.

In the Indian context, there is either silence about Freud, or he is cancelled on the assumption that he was misogynistic. I use the word ‘assumption’ because in my interactions with fellow feminists, I find that without reading Freud or anyone writing on his theories, he is dismissed as the guy who wrote about how women suffer from penis envy, lie about incest and mature only when they have a vaginal orgasm. To find out more about what he wrote and why, please see the references appended here.

Freud is also the guy who gave us a foundational understanding of the unconscious and its workings. It is only on the basis Freud’s work that concepts such as the ‘push paradigm’8 , ‘prohibition eroticises’9 , ‘lack’10, the ‘lost object’11 and the ‘big Other’12 could be developed by psychoanalytic thinkers like Bruce Fink and Jacque Lacan. The understandings about the unconscious that such concepts offer are critical for feminism due to several reasons.

First, as we have seen, these psychoanalytic concepts are necessary to reduce both bewilderment and judgement — regarding ourselves and others — on love and sex.

Second, as we have seen in the instance of yummy-yuckyness, psychoanalysis helps us move along the feminist mantra ‘the personal is political’ — from how the political informs the personal to how the personal can inform the political. This matters much, since as feminists we are in the business of analysing and challenging unjust power relations.

The limits of rationality in our personal lives, for instance, can help us see the limits of rationality in the play of power.

In these ways, Freud, psychoanalysis and feminism are already hand in glove.

The relationship between Freud, psychoanalysis and feminism becomes more complicated when we turn to how psychoanalysis understands sex and gender.

Some feminists have pointed to how Freud was only a product of his times, and thus reflected the patriarchy that prevailed in Vienna at the turn of the twentieth century. Others have argued that Freud was only describing (as it is the business of psychoanalysis to observe details) and not prescribing.13

A third set of feminists take us further into the relationship between feminism and psychoanalysis, when they don’t just defend Freud, but point to the ways in which Lacanian psychoanalytic thinking that builds on Freud, strengthens feminism. They also clarify that in psychoanalysis what matters is not the penis as a biological organ, but “a fantasised emblem of power and sexuality”.14

Similarly, it is not biological men and women that are the subjects of inquiry in psychoanalysis, but the ‘male’ and ‘female’ positions. A male position constantly seeks to obtain the symbolic phallus to fill the lack, as though that were possible.

A female position seeks to be the one who can fill the lack for the other.

Feminists like Elizabeth Grosz do not agree that the phallus or the male and female positions are neutral in terms of gender. Grosz argues that “the relation between the penis and phallus is not arbitrary, but socially and politically motivated”15. Although it is beyond the scope of this piece to delve further into feminist debates around the use of these terms, it is important to note that even as Grosz problematises them, she finds the relationship between psychoanalysis and feminism to be valuable enough to author a book entitled Jacques Lacan: A Feminist Introduction. This is not simply an interesting detail, but goes to the heart of how feminism may want to engage with psychoanalysis. In Grosz’s words, how might we want to “use” the work of psychoanalysts “to explain the (psychical) operations of patriarchy”16.

In patriarchy, the male and female positions get mapped on to biological men and women, that is, men are forever chasing lack and women are continuously casting themselves in the role of the object of desire. Such workings of the unconscious help us understand why patriarchy persists despite all the social and economic changes that have taken place so far, not least because of the struggles fought by feminists.

However, there is also hope. The phallus, even though it has powerful implications, is vulnerable because it is not real to begin with. The female position can challenge patriarchy because unlike the male position which is organised around the fantasy of ‘having’ the phallus, and therefore tied to mastery, wholeness and a fantasy of complete knowledge, the female position is defined in relation to ‘not-having’ the phallus, and therefore without the compensatory fantasy of possession. This absence in the female position can open space for other modes of desire, relation and knowledge that do not aim at total mastery.

It is from this place of radical uncertainty that change is possible.

- Georges Bataille, Eroticism: Death and Sensuality, trans. Mary Dalwood (Penguin Classics, 2001), 178.

- Sigmund Freud, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. and trans. James Strachey with Anna Freud (London: Hogarth Press, 1955) 12.

- Sigmund Freud, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. and trans. James Strachey with Anna Freud (London: Hogarth Press, 1955) 86.

- Richard Boothby, Death and Desire: Psychoanalytic Theory in Lacan’s Return to Freud (New York: Routledge, 2014).

- Richard Boothby, Death and Desire: Psychoanalytic Theory in Lacan’s Return to Freud (New York: Routledge, 2014).

- Richard Boothby, Death and Desire: Psychoanalytic Theory in Lacan’s Return to Freud (New York: Routledge, 2014) 86-87.

- Sigmund Freud, Beyond The Pleasure Principle (New York: Dover Publications, 2015).

- Bruce Fink, Lacan on Love (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015), 35.

- Bruce Fink, A Clinical Introduction to Lacanian Psychoanalysis: Theory and Technique (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 67.

- Bruce Fink, Lacan on Love (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015), 35.

- Bruce Fink, Lacan on Love (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2015), 79.

- Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York, London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1977).

- Juliet Mitchell, Psychoanalysis and feminism: A radical reassessment of Freudian psychoanalysis. (Basic Books, 2000); Elizabeth Grosz, Jacques Lacan, A Feminist Introduction, (London and New York: Routledge, 1990); Elizabeth Grosz, “Phallus: feminist implications,” in Feminism and psychoanalysis: a critical dictionary, ed. Elizabeth Wright (Blackwell Reference, 1992) 320.

- Elizabeth Grosz, “Phallus: feminist implications,” in Feminism and psychoanalysis: a critical dictionary, ed. Elizabeth Wright (Blackwell Reference, 1992) 320.

- Elizabeth Grosz, Jacques Lacan: A feminist introduction, (Routledge, 2002) 124-125.

- Elizabeth Grosz, Jacques Lacan: A feminist introduction, (Routledge, 2002) 191.

Read Part I, II and III here.

-

Jaya Sharma is a feminist, queer, kinky activist and writer. As part of Nirantar she worked on issues of gender and education for over twenty years, during which she was intensively involved in sexuality trainings for groups working with rural women. As a queer activist she has co founded queer forums in Delhi, including the coalition Voices Against 377. She is also one of the founder members of the Kinky Collective, a group that aims to raise awareness about Bondage Domination Sado Masochism and to

strengthen the community from within. Currently her writing seeks to explore sexuality through the lens of the psyche.