In November 2021, a group of eleven women found themselves sitting together in a room in Indore, Madhya Pradesh. Three of us (Anushi, Ekta and Angarika) had traveled from Bangalore, and the rest from different parts of Madhya Pradesh. There was a nervous energy in the room. “Why do you think we’ve all come here?”, we asked the women. “Natak banana hai (We have to make a play),” said one of the women. “Apni kahani, apne tareeke se darshana hai (We want to tell our stories on our own terms).”

The Making of Freeda

In 2018, maraa was asked to document the experiences of women who were part of a network that had formed to challenge caste-based sexual violence. Traveling across 22 states, Anushi and I were expected to interview the women to understand the essence of their struggle, which ranged from casteism, indifference of the legal system, humiliation, isolation within the family structure, and the burden of blame for what had happened to them.

Their experiences were difficult and visceral. When they began sharing, each story felt like a punch in the gut. Buried deep inside the facts and chronology of violence, there was a body that had endured it. But somehow, there was no room for emotion. “Don’t cry, it makes you appear weak,” the women were constantly told by members of the organisation, as they stood in front of an audience, preparing to share their experience. As the people behind the camera who were conducting several interviews in a day, somewhere, the task assigned to us took precedence. As we kept listening, our responses began falling into a pattern.

In the way our body adjusts to harsh seasons, the more we heard accounts of violence, it went from feeling exceptional, to routine, to almost mundane.

To ensure that these stories were heard by the police, media, and various government representatives, it was our job to pack these experiences into tight testimonials. Whose stories get heard? On what terms? From which perspective? These were some of the questions we were grappling with as we traveled across different geographies.

We returned to Bangalore with heavy hearts and heads. On our return, our colleague at maraa, Ekta made a suggestion: “Pause; maybe you need to process what you heard and experienced; theatre could be one way.” Somewhat tentatively, we agreed. We approached Anish Victor, a senior theatre practitioner, to teach and guide us into what was, essentially, a completely new world for Anushi and I. More than our opinions and analysis, he asked us to place our bodies at the centre of our exploration. How does the body witness? How does the body store memory? What are the incomplete conversations in a woman’s body, in the aftermath of violence? Navigating our way through these questions, we arrived at a performance called ‘Chhu Kar Dekho’.

Based on personal experiences, the performance was based on the body’s experience of witnessing and experiencing violence.

In one scene, Anushi is sitting and braiding Angarika’s hair. She tells the audience a story about the expectations that exist between her and her mother. Left unsaid, yet strongly sensed, these expectations have formed a rocky silence. The scene touches upon how desire, fear, and tradition get passed on between generations.

In another scene, Angarika shares a personal experience of violence with the audience. It is set up as a game, where the instruction to the audience is to clap every time they want to hear a different story. But the story does not change. Instead, each time the audience claps, Angarika re-narrates the same story, and gradually, the narration loses its emotion and is reduced to bare facts. The scene dwells on the effect of repetition on the relationship between speaking and listening.

The process of making theatre was transformative for us. We explored different perspectives from which we could tell the same story. We sensed what our bodies might be saying, in contradiction to reason or logic. The discussions we had with different sets of audiences after the show made us realise how theatre can provoke an audience to reflect on their own experiences, prejudice, and complicity.

Theatre became a space for both, confession and confrontation.

Having experienced this, we were keen to take the show back to the women who had inspired its making – the women we had travelled with in 2018. We took the performance back to Madhya Pradesh. As we performed for them, the lines between audience and performer blurred. They began responding to our questions and completing our dialogues. For instance, in one of the scenes, Angarika is trying to get ‘home’ but Anushi keeps stopping her, giving various reasons as to why the routes are blocked. The blocks are examples of social morality, and the reasons begin to grow more ridiculous as the scene progresses. At some point, Anushi and Angarika start posing the questions to the audience. Anushi’s character represents an older, cautious morality while Angarika’s character is full of resistance and playful exploration. The audience began to respond, and the scene transformed into a debate on the ways in which women navigate social boundaries. It felt as though the women in the audience were breathing with us as we performed. At the end of the show, we asked them, would you like to make theatre? With this, the journey of Freeda begins.

****

Touch and Sense

When we read or listen to news about violence in the media, what do we feel? The news might induce a state of shock or complete saturation. Violence is reported through the shock of headlines, with a lecherous eye for certain kinds of details. In the development sector, measuring violence sometimes means reducing it to statistics or rhetoric. Often, there is an overemphasis on legality, which means that conversations around violence revolve around the incident of crime, victim/perpetrator, evidence, proof, and justice within a courtroom.

These are necessary responses.

Yet, can violence be addressed adequately only through the arm of the law?

Listening to the experiences of women who have endured and fought against various forms of violence dispelled the stereotype of violence as something ‘external’. Instead, we learnt about how the familiar is often the most violent, the cause of immense hurt and grief, and collective trauma.

In the aftermath of violence, the body is made to cover itself in shame. Yet, there remain dormant desires, small resistances. “If I wear lipstick, or put on a new sari, my family turns around and tells me, why are you getting so dressed up? Have you forgotten what happened to you?” shared one of the members of Freeda, in one of our initial meetings. Their experiences revealed the moral repercussions of violence that perhaps seep through deeper than the incident itself. For example, the common assumption that if a woman has undergone sexual violence, she will never experience desire. Or getting the woman married off quickly as a way of regaining lost ‘honour’.

As an arts and media collective, we have been committed to the politics of cultural justice: a way of responding to injustice, exclusion and appropriation faced by communities who have been historically oppressed.

Cultural justice embodies the politics of aesthetics: what gets constituted as knowledge, who has the chance to tell their stories, and on what terms?

We wanted to open a space of creative expression for the women, so that they could find their own ways to heal from their experience, and share their stories on their own terms. We believed that making theatre is its own form of healing: in the act of creating, there lies agency. In working together on the floor, they felt less alone. In reactivating a connection with the body, they experienced a release. “Earlier, when the memory of what happened used to come back to me, I would get stuck there. It felt like I was drowning. But working on the performance has given me a way out. In some ways, I finally feel free of my own story.”

The three of us often found ourselves grappling with various uncertainties, since the performance was devised from lived experiences. Was the process leading the women to re-experience their trauma? What was the effect of repetition on them? Given that we came from different social locations, to what degree should we ‘direct’ their experiences? After one very difficult rehearsal, we decided to put these questions to the group. “Sometimes when we do that particular scene, I relive that very moment again. My head becomes very heavy. It is difficult. But then I remember that I am not alone. I can sense the others on the stage with me. And that gives me the courage to move forward.” Another member shared, “When we cry during the performance, it is because some wounds are still fresh within us. But I also experience release. I don’t feel as suffocated as I used to. The heart grows lighter when you find a space where you can share your experiences.”

Working together on the floor also allowed us moments of suspension. Each workshop would end with a dance party, where all of us would let loose. In these moments, we would experience a visceral connection that is still, at times, difficult to articulate. We wanted to ensure that the process of making the performance remained within the spirit of collaboration. We consciously chose to stay away from ‘direction’ in the conventional sense, allowing for experiences to emerge without a predetermined agenda or frame. Having experienced the possibilities of theatre , our intention was to try and create a similar experience for the women.

The three of us also participated in all the exercises, to acknowledge the differences between us and them. We shared our reflections and questions with the group, including moments when we felt vulnerable as facilitators. This helped us to grow closer. We found a space to acknowledge our difference and privilege, while also discovering the common threads : our own experiences and struggles with morality, family structure and the boundaries of freedom. Instead of themes and topics, we offered prompts, clues and hooks. We also provoked them to think of different ways of telling a story; to challenge stereotypical representations so that they could communicate clearly with audiences. We introduced them to theatre and movement techniques they could use to construct the performance.

One afternoon, we asked, “What does freedom mean for a woman?” The group was divided. The younger generation argued for change, for a different way of looking at the world. The older generation sat staunchly at the other end of the line. “How can a woman ever be truly free? Freedom can’t just be taken, it also has to be given.” These arguments carried on well beyond rehearsals, and often, the three of us would find ourselves returning to the points raised, debating our own perspectives and positions. These debates found their way into the performance, opening up the larger web of moralities, restrictions and boundaries that as women, we often find ourselves curtailed by.

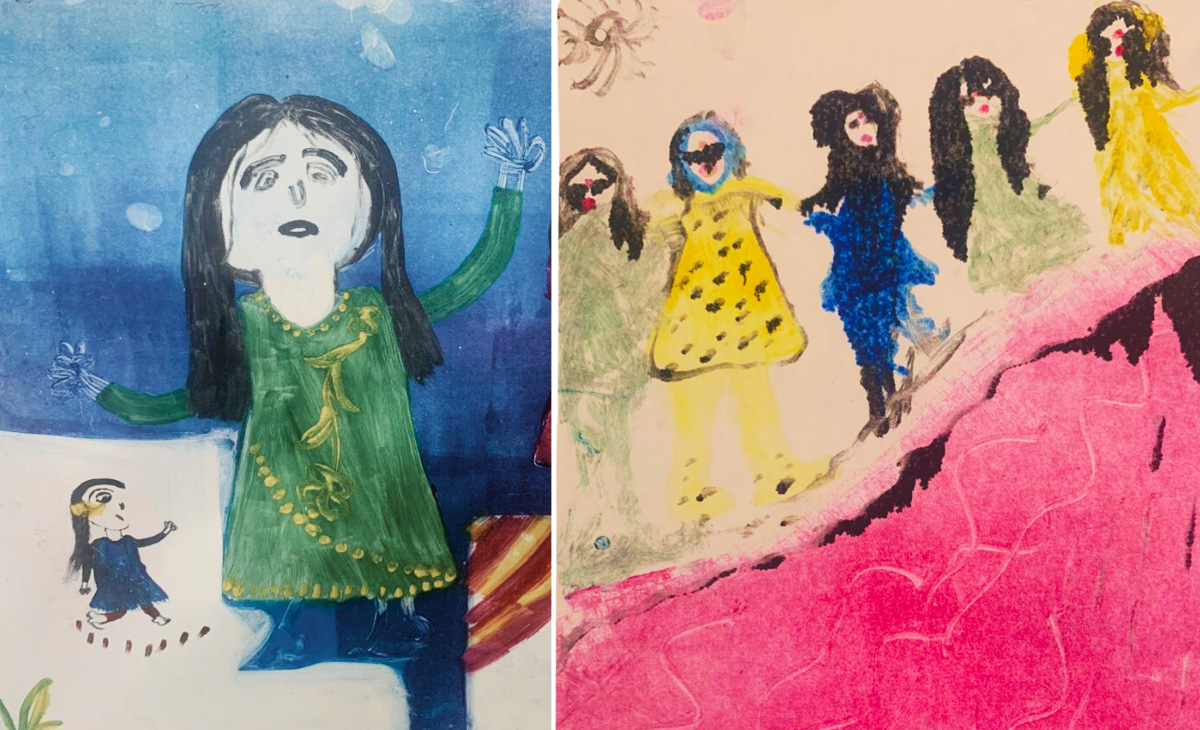

Given the lack of formal literacy due to caste discrimination, we could not rely on writing as a form of reflection during rehearsals. Instead, we turned to drawing as a route into our memories and sensations. Past, present and future exploded in colour, with various figures and creatures coming to life on paper. These drawings became symbols, images, and metaphors in the performance, creating a narrative that flowed between reality and fiction. For example, some props represented the reality of her daily labour, while others represented her desires and resistance. Instead of specific incidents, facts, or events, we relied on desires and memory.

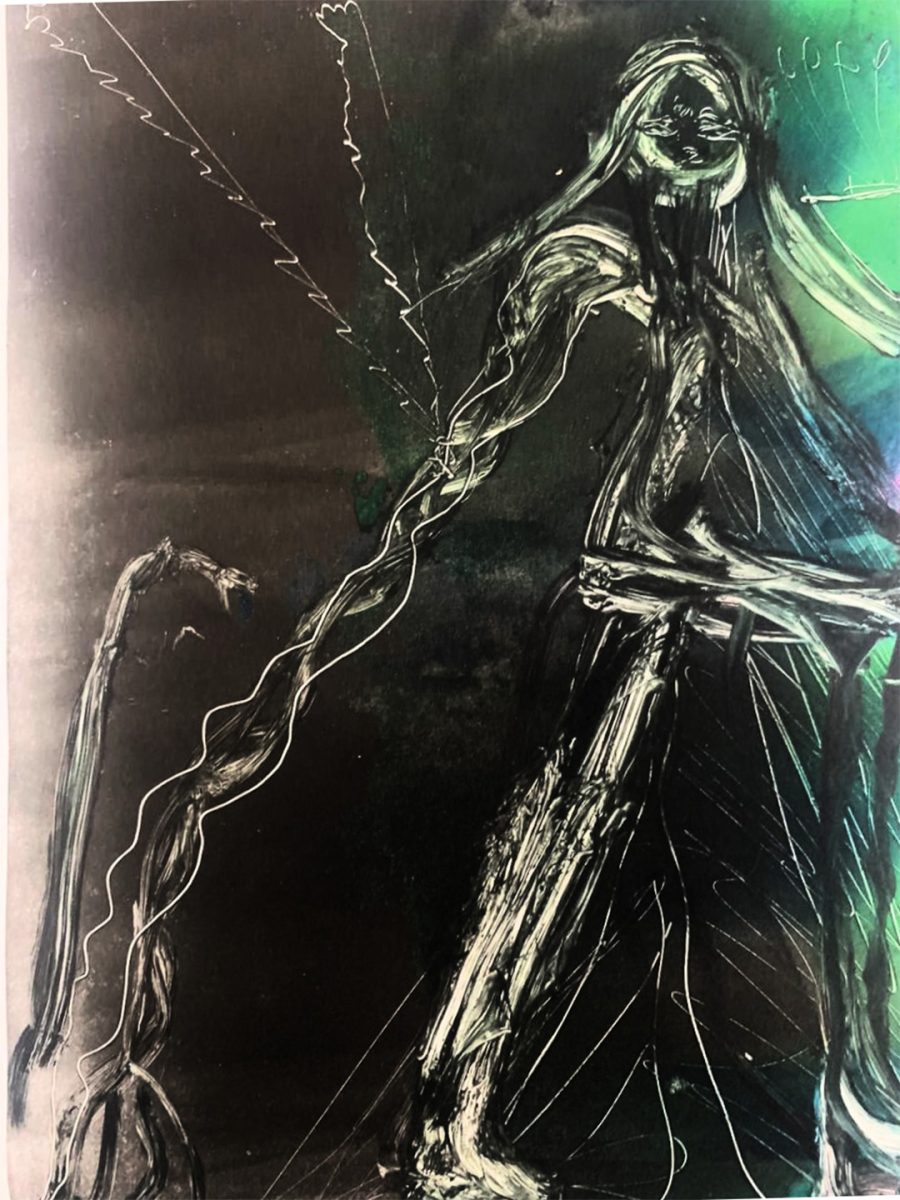

Much like the process of dreaming or remembering itself, the narrative of the performance emerged, fragmented and partially visible.

“We have tried to speak and share our experiences for many years, but no one has listened to us. Through this performance, through our props and objects, through our bodies, we hope the audience will be able to sense what we have been through.”

Placing the Body at the Centre

The association with touch was initially tentative and full of risk.

We facilitated a movement exercise which required one partner to stand stationary, with their eyes closed. They had to imagine themselves to be a statue. The other partner was asked to gently touch their partner, as though they were an artist bringing their statue to life. The emphasis was to try and keep the touch as neutral as possible. In a social context where touch is laden with so many different connotations, the imagination of a neutral touch, was at first difficult to grasp. Slowly, the feeling was embodied. The body began to awaken, as though from a deepsleep. Forgotten, suppressed, dormant desires began to emerge. As one of the actors shared, “For a long time, I have remained trapped in silence. I had lost sense of my body. But theatre has helped me regain my consciousness. I can sense now, how each part of my body speaks. How each part has something to say.”

The caste locations of the participants also revealed a collective body that had been through generations of discrimination and abuse. The women shared stories of hunger, long hours spent working under the blazing hot sun, poverty, the yearning to study, and resisting marriage. We created scenes around a woman’s labour — at work, at home, through pregnancy, and the constant nurturing of family. We explored desires that were taboo within patriarchy: to look beautiful, to study hard, to live alone, to fall in love. Slowly, as the bodies began to speak, the impulse to explain everything gave way to bodily sensations. The scaffolding of the performance was set in metaphors, rather than descriptions.

From the very beginning, the women were certain that they did not want to make a play about ‘survivors’, nor did they want to be identified as ‘survivors’. The body does not forget the memory of violence, but the richness of life’s experiences cannot be reduced to one event.

However, it is often expected that people who have experienced oppression must speak only about their oppression.

They must share their experiences in a monochrome of violence and discrimination. Further, there is an expectation that a performance from a rural context will either be traditional, or fall within the genre of awareness-raising, demanding a ‘solution’, or ending with a social message. Working on the performance became a way of reinvention, of the freedom to represent oneself differently.

In one of the workshops, we asked the women to play their favourite childhood game. Kabbadi emerged as the most popular. As both sides squared off, all our bodies transformed into a tangle of limbs, sweat, laughter, and good-hearted competition. As we sat later, catching our breaths, we drifted back to the landscape of childhood; the smells, tastes, sights that brought back memories of freedom, but also violence. As one of the women shared, “I grew up in dire poverty. There was never enough to eat in my house. But I was always hungry. Nothing could satisfy my hunger. In a fit of anger, my father would often tell my mother – let us bury this girl beneath the cot! Why is she always hungry? A girl is not supposed to have such a large appetite.” This deepened into a conversation around ‘hunger’. What are the different kinds of hunger we experience? Does a woman, in this context, ever experience fulfillment or satiation of her hunger?

I bought my first pair of earrings for Rs 10.

I was never allowed to wear it at home, or outside home.

They say that kind of jewellery can only be worn by the higher castes.

So I used to hide and wear it…it was my little secret.

I was married off at the age of 13.

I had no idea what it meant to be a bride.

So even in my in-laws house, I would spend all day outside, playing games.

One day, I remember seeing a tree filled with the ber fruit in our neighbors compound.

It was my favorite fruit and I had not tasted it in many days!

Without thinking twice, I scaled the wall, and climbed the tree. I came down with a fistful of ber, and took one bite.

My mouth was filled with its sweet juices.

Suddenly there was a hard slap on the back of my head. It was my husband.

The juice of the fruit mixed with the taste of blood.

Looking back, that was the moment I lost my childhood.

In another workshop, we asked the women to transform into ‘mirrors’ for each other. The exercise revealed constant action. From morning to evening, there is barely a moment of rest. There is no moment when she might glance at the mirror and take a closer look at herself. “Why do you want to look at yourself after what has happened to you?” is a taunt she often has to hear. ‘When they get a girl married, they want her to look beautiful. They pierce her nose and her ears. But when she wants to look beautiful out of her own choice, everyone is quick to raise an objection. Sometimes you want to look beautiful and sometimes you don’t. It should be our choice, no?” shared one of the actors after the exercise.

The performance is titled, ‘Nazar Ke Samne’. That which takes place right before our eyes. Are we willing to see? Do we consciously choose our own blinkers? As much as the performance stands against violence and discrimination, it also stands for the right to beauty, the right to lay claim to our own bodies. Later, as we began travelling with the performance, many audience members remarked on the ‘beauty’ of the play. Perhaps we are accustomed to a particular aesthetic when it comes to representing violence: a woman crying, screaming, her hair wild and unruly. But the performance became a space for claiming dignity. It allows for whispers and confessions. By a woman who runs away with her lover from another caste. A woman eats to her heart’s content. A woman who takes her time before a mirror, getting ready. Mother and daughter who look at each other closely, as if for the first time. Theatre becomes a space not just to state what’s wrong or what isn’t, but to provoke and suggest: ‘What if?’ and ‘Why not?’

*****

Nazar Ke Samne

Before Your Eyes

During our tours, we found ourselves performing in a wedding hall used for community weddings. In their usual spirited way, members of Freeda dedicated that show to all the young brides who feel stifled and coerced into getting married;

Before one of the shows in Chhindwara district, Madhya Pradesh, we stood together at the village chauraha (crossroad), having a cup of tea. Later, a few of the women from the village, who had accompanied us, confessed that they had never dared to have a cup of tea there. The practice of theatre innately questions boundaries, poses a question. What if a woman could carve out time for herself? Perhaps, this has been one of the most precious aspects of our tours — that women can take 2-3 hours off, just to huddle together and watch a performance that speaks so closely to their lives. Why must a woman define herself only in relation to the structure of the household? What can be provoked if she is presented with a different imagination? What happens when a woman takes the stage? In other shows, a discussion emerged on the silence and frustrations between mothers and daughters; on traditions as daily habits; on the fear and desire for beauty.

“A few years ago, we were sitting there, in their place. Now we have crossed over, and we are on the stage. That is the strength of our work: to find a way to help more women open up, and make the journey that we have made.’. This is the ground on which Freeda’s work stands. As Freeda’s journey continues, the three of us travel along, as co-collaborators. As the performance evolves, so do the actors. We are trying to find ways to document these changes, in all their ephemerality, fragility and strength. How do a group of women from difficult social contexts, find a way to stick together against all odds? To deal with suspicion from family members, jealousy and fear from loved ones, precarious economic conditions and so on? The commitment to theatre keeps us going. Our friendship continues to evolve. Collectively, we imagine Freeda as a spark that can perhaps build a different kind of social movement: a theatre of resilience, where the body is placed at the centre of the conversation and justice is experienced through the stage.

Read in Hindi

Freeda Theatre is an inter-generational collective of women from Scheduled Caste and Tribe communities, in Madhya Pradesh, India.

Maraa is a media and arts collective, founded in 2008. Our arts and media practices are located at the intersection of gender, labour, caste and religion, rather than in a thematic focus on issues. We highlight imaginations and histories that are systematically suppressed, censored and reductively framed. Our work involves research, writing and documentation as well as curation, practice and production. We are attentive to differences in lived experience, worldviews and aspirations that can challenge the dominant frames within which knowledge is produced. We highlight daily discrimination, violence, resistance and resilience. We are committed to theatre as a form of assertion against oppression and a space of radical collectivisation.