In a Digital India discourse where we vow to ‘leave no one behind’, who has access to power? What does cashless economy mean for a non-literate rural woman? Is using a digital medium the same as accessing a digital world with autonomy?

In response to the changing paradigms of literacy, and to demystify the digital for the most marginalised, Nirantar’s Applied Digital Literacy (AppDil) program with women who run dairy co-operatives in Uttar Pradesh was a discovery in timeless chasms: “We asked women in rural UP in 2018, that what do you understand when we say digital? One of them said, “Kheto mein ugat hoi bahin? Hamare yahan nahin ugta hai yeh.” (“Is it something that grows in the fields? We don’t grow it here.”).”

The Third Eye in conversation with Purnima, Nishi, Anita and Kalyani, the architects and implementers of AppDil, as they take us through the analogue worlds within Digital India.

TTE: How did Nirantar’s three decades of work with women’s literacy, lead to this curriculum, that helps rural women navigate a digital world?

Purnima: if we are looking at the current moment in history, we have to look at technology and education as the new power structure. And like in any structure, it’s important to see who is celebrated by the structure, and who is left out.

Historically, if we look at literacy, its forms keep changing. There was a time when there were just symbols, which developed into a script. This evolution excluded women from the participation of the written script. Language and script became an area that gave power, identity and resources. Women were systematically marginalised from accessing any of this by keeping them away from the written word. As a self-fulfilling prophecy, this marginalisation led to the famous dictum – “Auratein yeh nahin kar sakti.”

In today’s world, it’s the moment of the digital that is enabling a new gender dynamic to play out, informing all language, script and literacy paradigms.

Anita: Nirantar’s approach to women’s literacy has always been about keeping contextual realities in mind. In the last few years, we have been watching the new areas literacy plays out in. It’s in the digitisation of banks, in using ATMs, in travelling on metros and navigating Internet bookings, while using the Aadhaar card, or when you get your ration in exchange of your thumbprint, it’s in the digital weighing machine. So, we were asking ourselves, are rural women able to connect their reading-writing literacy with this world, as it exists around them?

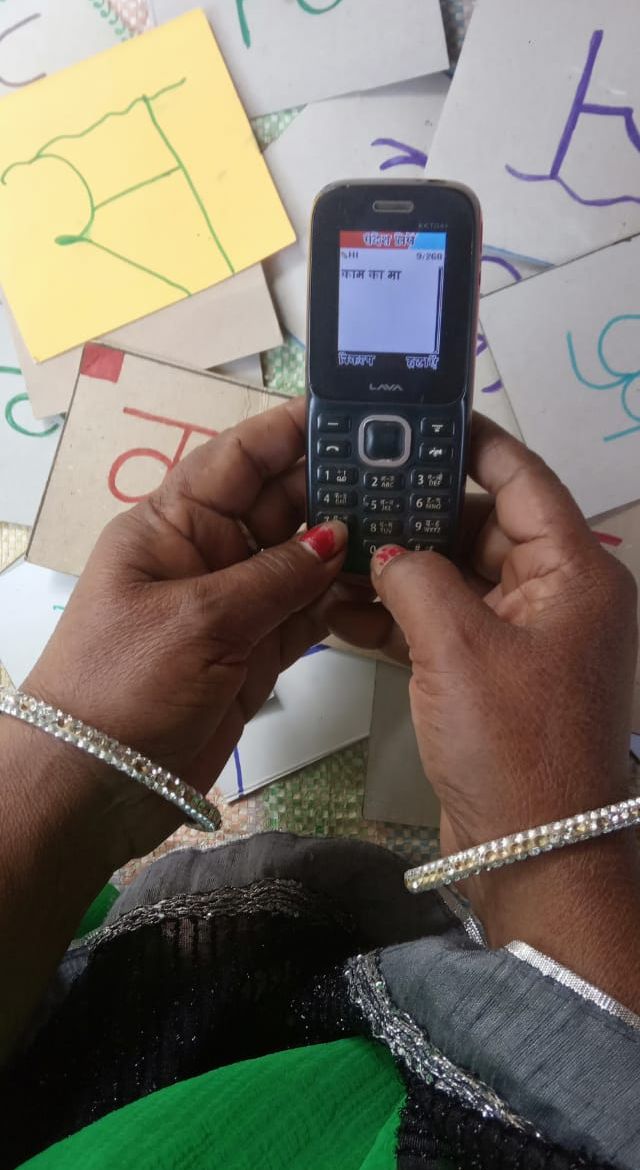

Nishi: We also started seeing that the new capacities we needed to develop are not just limited to filling of forms. And after studying the NDLM [Now PMGDISHA] program and its implementation we realised that the state’s attempts at bringing people into the digital had a rather narrow focus. It concentrated only on literate people. Which basically means, it leaves out a large section of rural women (among others). Our local coordinators started talking to us about the mobile, and the fraught relationship this piece of technology shares with rural Indian women. Rural women don’t own mobiles;also they hesitate to use them – milta bhi nahi, milta isiliye nahi hain kyunki logon ko lagta hai ki aapko aata nahi hai or aap kharab kar doge. So, we started thinking, can we connect literacy with the mobile phone?

What we started realising was that if literacy didn’t involve the digital world, you may remain non-literate, despite all traditional forms of learning.

Kalyani: There was also a demand at the national and international policy level, you know, for a cashless economy. Then demonetisation happened, and there was a claim of moving into this cashless economy. Even the Sustainable Development Goals carry a digital push with conversations around ICTs and technology and youth. So, there was a top down push, alongwith a demand from the field.

But as Nishi was saying, the place of the mobile phone in a rural woman’s life was most interesting. It met with the same question that women’s literacy had met three decades ago, “What will she do with it?”

You cannot separate literacy from digital literacy, and at a national level the latter was limited to opening and closing Skype, switching your mobile on and off etc. The Adult Literacy programme had been fully scrapped by 2018, and budgets and human resources had been pulled out of the Sakshar Bharat programme and redeployed into Pradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta Yojana. So then, we asked, in the absence of adult literacy initiatives, and in an increasingly digitised world, is digital literacy only about learning how to turn your mobile phone off and on?

Purnima: Twelve years ago, when we did our first computer and video training at Janishala, we saw how writing on the computer changed things for adolescent girls. Shayari likh rahe the, they were writing letters to their friends…they were so excited at the idea of not using pen and paper! Pen and paper gave them a certain confidence, yes, but the computer gave them something else – “Achcha maine ye shabd likha hai, or ab bina paper ko kharab kiye mein isko delete bhi kar sakti hoon, erase bhi kar sakti hoon… (I have written this word, and now, without spoiling any paper, I can even erase this word).”

Now, this was a new kind of excitement – the ability to delete gave a new kind of confidence to make mistakes. Your sheet won’t get dirty, it won’t tear if you keep rubbing out your galti ki maatra – in fact, you won’t see a hint of your mistakes!

TTE: What were some of the particulars of the landscape that your curriculum and pedagogy responded to?

Anita: We conducted our field survey in Pratapgarh, Lalitpur and Sirohi district.

We asked women, what do you understand when we say ‘digital’? Some asked, is that what they mean when they say ‘Padhega India, Badhega India’? In another village they asked us, “Is it something that grows in the fields?”

But, I think, the biggest revelation for us was that even the teachers we met were struggling to keep up with the digitisation of Indian public processes. Out of 30 teachers, only two knew how to use ATM cards, and 28 didn’t even have one. The backbone of any curriculum or pedagogy implementation is the teachers. And that’s when we started digital trainings, which showed us the huge distance between promise and access, and how gender determines it. Like, when we asked, “Aapne Jio ka naam suna hai, Jio jaante hai?” We heard, “Haan honge, koi suna toh hai par unko dekhe nahi hai. [“Have you heard of Jio?” “Sounds familiar, but have never met him.”] When we started talking about Facebook, women asked us, “Facebook hota hai kuchch lekin kyon mana kiya jaata hai?” (“I know there is such a thing as Facebook, but why are we asked to stay away from it?”)and “Ear phone lagane se kyon mana kar rahe hain pati?” (“Why does my husband not let me use earphones?”)or “Number aur phone toh diye hain per ismein itna lock kyon hai?”(“He’s given me a phone and a number, but why does the phone remain locked?”)

Answers to questions like these are what we have built our chapters around.

Kalyani: Our needs assessment made us ask a central question: what do we even mean when we say digital? It’s not just mobile, computer, ATMs… your thermometer is digital. Your pregnancy kit is digital. Your calculator, your clock, your calendar on your phone…for the people we talked to, digital was any piece of machine that had a non mechanical machinery. When we first went to Pratapgarh, it was to meet the Dairy Women’s Collective [GVSS]. At the milk pooling point, where the women deposit the milk, that whole set-up was digitised – from the weighing machine to the machine that tells you the NSF and fat content in your milk.

At national literacy summits you hear that first there should be literacy, and then digital literacy, which is totally contradicted by the reality on the ground.

Purnima: We decided that literacy and digital literacy couldn’t be separated in today’s world. They will have to move together. And hence, the program we designed combined all this – reading-writing through the language and symbols of technology, with the new mediums of expression, and with rural women’s lived realities. It builds an understanding of all of this with a gender and feminist perspective. The curriculum is implemented in 30 centres across Uttar Pradesh.

It’s very exciting for us. In the last year, we have received videos made by the teachers where we can see women typing SMSs, recognising the English language as symbols;they know what their UID number is, how many litres of milk they have sold, and can, in fact, write down the NSF and fat content of the milk. They are maintaining their own business records. It’s very challenging, but also very exciting.

TTE: Introducing a person or a community to a digital paradigm must come with this rush, but also as many challenges, especially for women in rural India? Could you talk about those? What are the particular conditions that a newly minted digital citizen negotiates with?

Kalyani: Privacy, for one. As we were saying, the excitement is palpable. One learner asked Anita, “Tum mereko digital mein YouTube sikha do, mein tumhe pasta banana seekha doongi. (“You teach me YouTube, I’ll teach you how to make pasta.”). So, yes, there’s potential, there is opportunity, but there are also threats. Like in Noida, we had an interaction with a transgender person who said,

We communicate through voice messages. Please teach us how to text. So that we don’t we don’t have to play our private messages in public places. We need the privacy of text.

Purnima: Which is what we mean by incorporating women’s lived realities into our curricula. Just literacy without understanding your gender position in the world is not enough. The digital space is as controlling as it is liberating. If the mobile is a tool for enjoyment for women, then the same mobile facilitates a mechanism of control for her family. If she learns Facebook, makes new friends, uploads her photographs, it may become a cause of violence in her life. Like it happened with a teacher of ours; she uploaded a photograph without a goonghat and her husband broke her phone and beat her up.

Anita: So, women ask us to explain things in a particular way. “Aap mujhe ye batado ki yeh kaise voh mera pati na dekhe, settings mein jaake bata do mujhe” (“Please tell us how to keep our posts private from our husbands in settings.”) Or it’s, “Can you show me the settings that people from my village can’t see my posts?” Or they ask us to set a new password on the phones they are using so that “Ab dewar mere paas aakar password maange” (“So that my brother-in-law now has to ask ME for a password.”)

Nishi: A big conflict we were facing in the material we were creating, and the information we were giving, was that how do we incorporate privacy mechanisms within – and also manage to communicate the ways people can misuse your information online, how perceptions lead to real world repercussions – so to build all of this, simultaneously. Unless I understand the various structures of control around technology, that technology can’t liberate me.

It is said enough times, “Technology liberates women,” but we also need to say, “Yes, but technology also controls women.” Technology is not liberating for that teacher who came to our training with her husband, who told us, “Activate location for whatever you set up for her. If it’s Gmail, activate location there too. We need to know where she is at all times.”

Kalyani: We have to strike a balance between caution and opportunity…

Purnima: It’s true that surveillance is a reality everywhere. But it’s important to look at access to the digital through the lens of rights. To be able to communicate that it’s your right to be able to access the digital world and all the information, journeys and experiences it contains.

It’s important to note that the digital world is very masculine in its language and expression and marginalises anybody who doesn’t fit into the masculine visioning of the world. So, for us, it’s important to bring those voices back in. Despite the trolling, the sexist, casteist, classist cyber bullying and commentary, we are trying to communicate to women in rural India, that you speak, you participate, this is your world, too.

TTE: How did the lack of ownership of mobiles and computers affect the transacting of the curriculum to the women?

Nishi: So, we took a stand. We told the women that if you want to learn something, then you have to have that piece of technology with you. Because, in our previous experience of teaching the camera or the computer, if the learners didn’t have it with them they forgot. Of course, the teachers said it’s too expensive to buy a mobile, but on further conversations we discovered that an expensive bike had just been bought for the husband, or a huge sum had been spent on a wedding. So, we had to motivate them into giving themselves value, and say that it’s okay to spend on yourselves. Today, many women own their mobile phones and bring them to the centres.

We have to look at knowledge and resources together. When your resources are in your control, and when you have a perspective and an understanding about those resources, then it leads to actual control over your life. You can make your choices. Do I want to upload a photograph in a ghoonghat or without? How do I want to reply to this SMS? When women own their resources, they can make more sophisticated negotiations with the systems around them.

Purnima: Our job is to communicate to women that knowledge is your right. With knowledge comes the ability to explore and to build a life, a livelihood. You understand how to make your voice be heard. You can articulate. Then you are free, it’s your world.

TTE: Going forward, what are some of the ways your curriculum may evolve? What other debates would you like to bring into rural women’s lives?

Purnima: We are deeply aware of the fact that the minute you enter the digital world, you are data. It’s something for all of us to think about. Even if you look at the National Education Policy of 2019, it talks about artificial intelligence, and that students’ data will be stored in national archives to determine ranking of universities and subject/‘recommendations’ for students. So, there will be national repository of your educational data and mark sheets…

Now, the repercussions need to be thought through. It can lead to life long digital discrimination, which will only magnify the caste-class-gender discrimination, as it already exists. We are seeing how to build perspective on this, through our curricula.