Vamsi: Hi, my name is Sri Vamsi Matta, or simply Vamsi. I am a Bengaluru-based theatre artist who has been involved with the theatre fraternity for over a decade. Post my graduation from the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, theatre became an integral part of my life and a full-time profession. My practice is influenced by my Dalit identity, experience and location, which inform the questions, topics and mediums I engage with.

Harsha: Hi, my name is Sri Harsha Sai Matta, or simply Harsha. I’m a student of history and currently pursuing [my] PhD from Ambedkar University, Delhi. I meditate on the historical understanding of caste, community, identity, and what constitutes the Dalit movement in Telugu-speaking regions in a longue durée sense. And this is all informed by my identity and experiences of growing up and becoming who I am today.

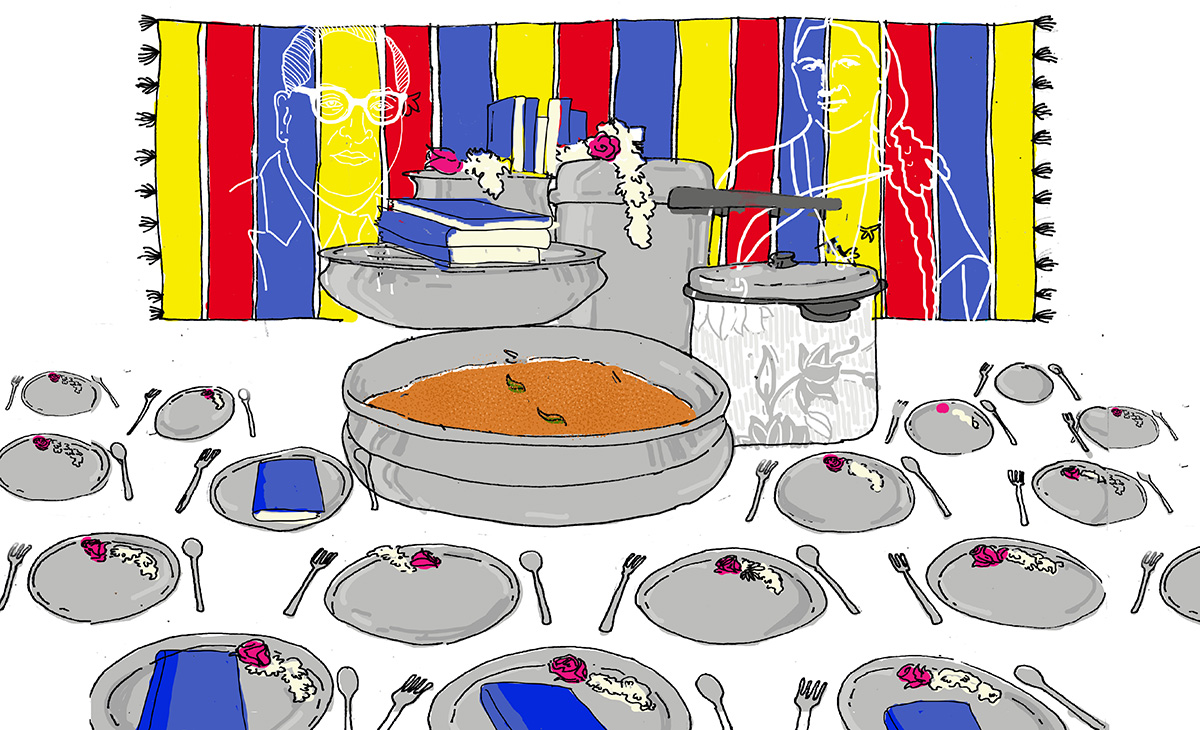

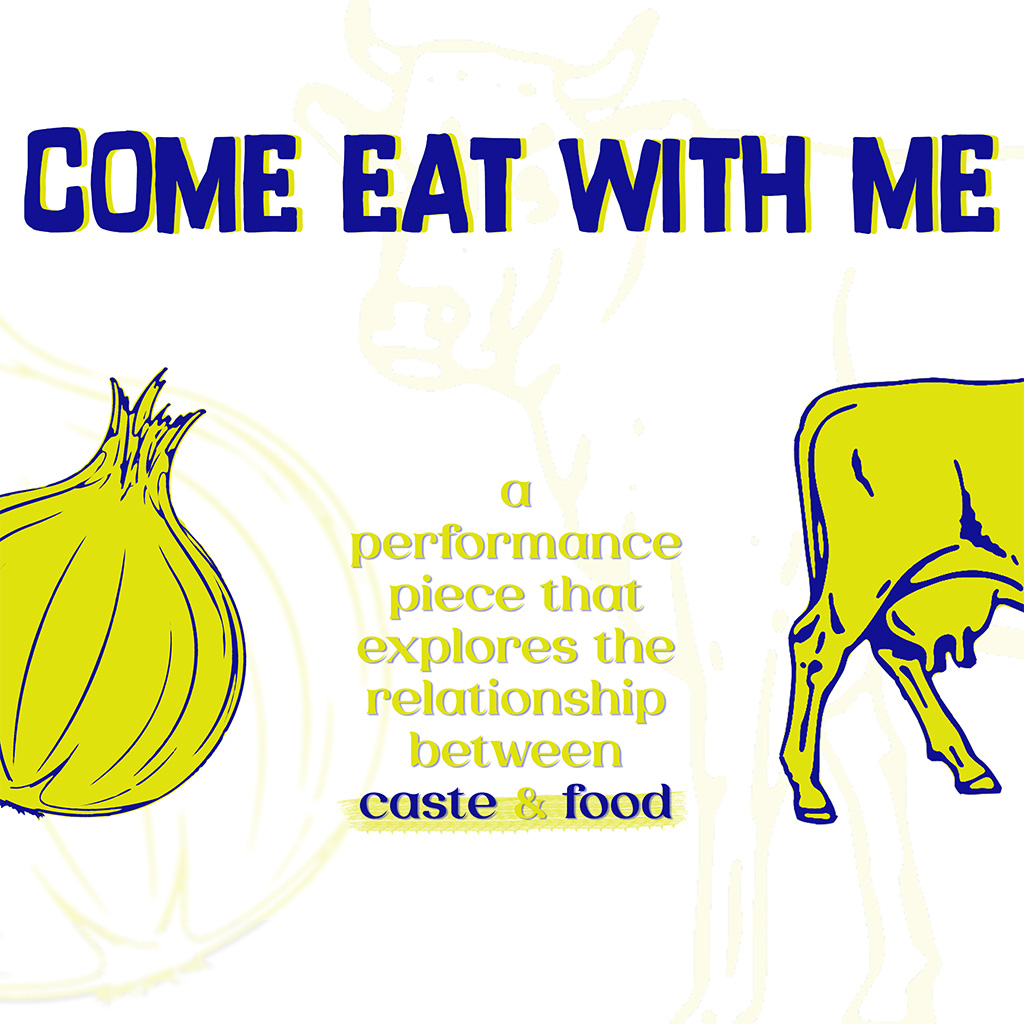

Vamsi: Come Eat With Me is a performance piece that explores the relationship between caste and food while sharing a meal together. Focusing on Dalit cuisine, the piece begins with personal stories and oral histories around food in my household and community, and it is peppered with existing literature and academic writing around the multi-layered, many-flavoured relationships between caste and food. The piece unpacks questions of oppression and solidarity, grief and joy, and the everyday victories of the human spirit in the face of structural injustices. Audiences are invited to eat together and share their own stories about caste and food. The project started as a journey of finding out more about my food and my community’s food. There is no ‘one’ Dalit experience; food practices among Dalits aren’t homogenous across the country. And now it has sort of evolved into an event that will/has to find its place in the more significant anti-caste movement, in the Ambedkarite movement. The content of the performance piece expanded in time and space, and the stories I share range from mythology to the undisputed present reality.

What you as a reader are going to witness below is an intimate conversation between two brothers coming from a Dalit family about the show, Come Eat With Me, and its politics. One of them (Vamsi) is the creator of the show, and the other (Harsha) is the brother of the creator who has a view into its making and was also an intern for a leg of shows for six days.

On a cold night in Delhi, Harsha opens his laptop to join a Zoom meeting, and Vamsi is waiting in his new apartment in Bengaluru.

(Edited excerpts of the conversation that followed).

Harsha: When I read Rahee Punyashloka’s notes on Come Eat With Me on Locavore, I kept wondering why he went to such an extent as to contextualise it so beautifully, both historically and, more so, personally. So many have interviewed you about Come Eat With Me but nobody wrote in a language like [Rahee] did, a feeling only we can feel as our own. It drove me mad-crazy after reading Rahee’s Strange Fruit: Or to be a Dalit, and Eat. It felt like a threnody on how, as generations of Dalits continue to suffer under the shaming gaze of the caste people at the things they eat, the same food in restaurants abroad is given an orientalist exoticisation as traditional food from India. After reading Strange Fruit… now it occurs to me that he’s been grieving about the same things with the same passion.

Vamsi: That is what I think and this is the start of our conversation. Why are we talking about food? How are memories of food constituted? Because when we are talking about food, the first thing you relate with [it] is hunger. But for me or Rahee or you or Suguna Rao (our father) or Chandrakala (our mother), it’s not just hunger. There are various kinds of feelings. Like I talk about the memories of my mother and what they remind me of. In some households, we see if the mother doesn’t eat curd, the children too do not eat curd. So in the same way, what are the experiences and baggage Mom (Chandrakala/Ammulu) had about food? For example, when she talks about how it is to be the only girl among three siblings or her issues with Lichen planus. She is a doctor and due to her knowledge of nutrition, she fought many things like these throughout her lifetime and amid many social and financial constraints. “What do I feed my children?” was something constantly running through her head. She’s the only one who had to take care of us and this is the thing with all working women who don’t come from a location of privilege because there is no grandmother or aunt as in joint families to take care of the children. So when I’m dissecting her memory of food or her memory of cooking food, I’m also slicing through all the baggage of the memory of food she had. This is not a memory that’s there: it’s retrofitted because of the shielding that mothers do. So all the memory I had up to a certain age is my mother’s food memory and so is yours.

Harsha: To look back at eating the way you or I eat, it is a practice she sort of imbibed in us, i.e. to get fed properly. When I go to friends’ or cousins’ places, I find that they eat they don’t like this or they don’t like that. When they leave food on their plates it makes me uncomfortable. The way we eat food is indeed really shaped by Mom; what she felt and believed in about food. And, yeah, really her role as a doctor or as a nutritionist also plays out in terms of how she organises the nutrition of the people in the household.

Vamsi: If you look at any Dalit autobiography, their struggles are very much documented in terms of the food they eat. It is not a coincidence and this is a pattern that follows through. So why is memory important in Come Eat With Me? For example, when I went to perform in Buddi Deepa, Kolar, on Ambedkar Jayanthi, I met VLN who narrated his love for rice and ghee. His family staple food has always been ragi mudde but VLN hated it so much. When the family’s finances worsened, they continued to thrive on ragi mudde. But VLN would not eat at all. [His] mother struggled to fetch rice, but somehow she managed to feed him. VLN talked to me about the joy he felt as he saw rice on his plate. And that is it. I wanted to have that human moment, a human expression. Because it’s not only about pain like in the story of Yendapalli Bharathi’s brother who was shamed by a teacher for carrying roasted beef in his tiffin box.

Yes, there is pain and how many times do we talk about pain? We are not locations of pain. We are much more than that. To sort of find that space and tell that story is what Come Eat With Me has become. It started as a personal project—like a personal travelogue—but then became more about me and you, our Dad, our Mom, our grandparents, our ancestors, and how their traumas are passed down as intergenerational traumas. I think these joys, eccentricities, intricacies, and finances are deeply entrenched in our memories. So food in itself becomes both a location of oppression as well as revolution. I want to tell about all the pain of a Dalit when they can’t eat what they like but also the joy of a Dalit when they get to eat what they like. How I pay tribute to the memories is what Come Eat With Me is all about, and one aspect of that tribute is joy.

Harsha: That food as a location of revolution you were saying is all about that joy, isn’t it?

Vamsi: Yes. And as much as it has been the direction for my process, it also has become a practice. How do I articulate joy? I’m not trying to retrofit it. I think that is where it sort of opened up and became inviting. I’ve found a balance between confrontation and inviting. There is a lot of rage and I would like people to witness that rage, but what else I can do? What does channelling my rage mean and especially through a performance piece that is so personal, that is so triggering and that is so encompassing of all these feelings?

Harsha: When you talk about the joy of a Dalit when they get to eat what they like, I remember this incident Ambedkar writes about in Annihilation Of Caste—of an Untouchable pilgrim who served a lavish ghee dinner to his fellow Untouchables. As the Untouchables began to partake of the dinner, the Hindus in the village got angry and beat up the Untouchables with lathis and razed to ground (sic) all the food. Ambedkar writes that even when an Untouchable can afford ghee, he can’t consume it because it is polluting and indignating (sic) what is restricted only to the caste Hindus. Somewhere else Ambedkar writes on how Gandhi opposes inter-caste dining and marriages, and asks that even if inter-dining is capable of producing good, why do you oppose it? The reason Gandhi cites is staggeringly absurd. He likens eating food to answering [a call of nature], and thus a filthy act needed to be done in isolation. I feel like Come Eat With Me is a larger Ambedkarite legacy where these things that Gandhi considers very polluting are to be so immediately performed, thus imbuing the spirit of Annihilation Of Caste.

Vamsi: This is so important—why he opposes inter-dining and what it means for us. So how Come Eat With Me is still about food? Dalit food? Let’s try and define what Dalit food is. By calling it Dalit food, I’m making it explicitly political. I think I’m envisioning a society where Dalit is not only about my Untouchable identity, but also a political identity. What I stand for when I want to talk about Dalit food. It is not just about my identity, but also about my politics. Not just the politics, the fight, the celebration, the joy, and the legacy. And to understand legacy, asking who can have legacy. Why can’t a Dalit woman like Dr. D. Chandrakala (Ammulu), born in a Mala hamlet in East Godavari district, have a legacy? And that is how the idea of naming the dish emerges. So by naming the recipe after the Dalit woman who cooks it, we create legacy: that is both celebration and part of the struggle. This embracing of identity comes from years of struggle. So as much as it is about Dalit food, it is also about Dalit politics.

Harsha: As Rajyashri Goody says, there is no Dalit cuisine as such in history, but in the same way it is not exactly like you all are seeking it, discovering it or something. But this identity formation as a Dalit—ever since Phule or Ambedkar or during the Dalit Panthers in 1970s—is a political construction as it is also emanating from the experiences of untouchability and oppression. Just like how the term Dalit is fighting the polluting names given by the Savarnas – like Harijan, Chamar, Pariah and Panchama – the term Dalit food is also such a political construction [that] artists like you and Rajyashri wish to constitute emanating from the very same location of untouchability and oppression.

Vamsi: I’m also working towards piecing together various memories. For example, when someone makes a comment on someone’s food, be it on social media or in the classroom, it does not affect just the person who was targeted, it affects everyone whose identity is that. People keep asking me what are the reactions of your audience. One set of audiences is largely the Savarna audience wanting to learn more and get initiated. Do I want to shock them? No. I want them to reflect—not about the other, but their own food practices. What is their connection with food? What food they do or do not wish to share with others? And the rest of the audience—the Dalit, Bahujan, Adivasi and everyone from marginalised identities—I want them to be heard and tell them that we are not alone in this. Ever since I started theatre and ever since I began reclaiming my identity and became political about it, I’ve started looking for fora, spaces, texts and performances. Will they talk about me? Make space for me? That was all I was in search of when I started making theatre for myself. That is where I found my space and I want this space for all the unheard marginalised people and their stories. Right now, in this country, everything and everybody is getting homogenised—being boxed into one thing. Since you are a Dalit, you eat this meat, you eat these vegetables. But how different is each of our upbringings as well as our experiences with caste and food! And the moment you say it loudly, multitudes of people and their stories start becoming visible to us.

Harsha: “Will they allow a Dalit man to cook, speak, eat his food and listen to him?” Earlier, when I read these lines in interviews about Come Eat With Me, I was wondering all the time—you are an established theatre person already, reaching out to the audience and accessing some kind of space. I kept wondering what difference it is going to make after you come out as a Dalit artist. But suddenly it also felt powerful when I realised that you want to be accepted as a person whom you’ve been hiding all the while as well as recover that Dalit person who was excluded, marginalised and kept away for ages.

Vamsi: Yes, absolutely.

Harsha: “As part of this project, I want to access these spaces and hope to reverse the erasure through interaction, debate and the process of creating language around caste and how food acts as a metaphor for cultural hierarchy.” I think it’s very powerful to look at it.

I want to bring in the idea of a Dalit kitchen or a Bahujan kitchen as a notion for building my setup.

Harsha: When you are talking about aesthetics, like for example, people want a neat kitchen, what occurs to me is that a standard has been put up by the upper-caste households and the responsibility to keep up the standard has been weighing upon the women in the household. So when one says things are shabby, things are here and there—who decides how a kitchen should be? There could be real stories when someone might not have eaten someone’s food at their home because they found the kitchen to be dirty.

Vamsi: The idea of dirty follows from the notion of purity—the patriarchal and Brahmanical idea that ‘oh it is unclean, so aren’t there any women in the household.’

It is unclean for this reason and all. What does that say?

Isn’t that how caste and patriarchy work? By saying that woman has to be in the kitchen because she has no work outside. The moment she leaves for work there’s no one to clean up. So how is it defying the laws of the land? The Smriti? How is that seeping into the practice? And the idea that everyone has to serve their own food in Come Eat With Me comes from these notions. You’re going to pick your ass up and no one is going to pick your plate for you or clean up for you after you ate. These aesthetics learned from a Dalit Bahujan kitchen follow through in the aesthetics of the performance.

Harsha: Talking about aesthetic, you told me earlier that someone commented on your reading from the sheet of paper felt odd to them and that it would have looked good memorising and performing like in any theatre show. But I felt it was very powerful—the sheet of paper along with Ambedkar’s photo, Amma’s photo on the table, and the jasmines you put on your hair. Holding a few sheets of paper from which you read poetry, some news reports, and lines from other writers and artists, in a way bringing forth all the repository of anti-caste stories and memories in your voice. Be it Kalyana Rao or Daniel Sukumar or M. Suguna Rao or Rahee or Ambedkar himself.

In that way, a sheet of paper mostly seen in rehearsals of a performance is becoming a tool here. For you to dig up all the space and world of memories of food and caste, Come Eat With Me wishes to create, and inhabit.

That paper felt like a device a tool to push discourse, to speak the anti-caste language in terms of performance, memorialising, remembering and fighting these images. These bad images…

Vamsi: I am indeed fighting these images. It is also like harking back to how people in the olden days collected recipes by writing on a piece of paper. When you are cooking, you want to replicate the recipe by looking at that sheet of paper. I want to invoke that. Apart from all the deconstruction, the fighting of the image, notions of what theatre is, what am I talking about? What is my tribute to? That is where it has come from.

Harsha: I think Come Eat With Me did two things to me which felt very powerful. It was in terms of how memories at school stung me—when my bench mate brought a nice fried potato which tempted me a lot. When I asked for some, he [refused]. Many days I would continue to beg him, [but] he [would not] give me any, which was not the case with his North Indian friends when they came to him and shared food with each other. One day, the lunch period was coming to a close and I finished my lunch; meanwhile, that guy [beckoned] me and showed me his box. There were a few pieces of potato left and he signalled me to finish them. I suddenly felt a sense of discomfort and said I don’t want it. He gets to decide whether I can share his food or not and he will only offer it when it is unwanted or he has to find a way to dispose of it to take an empty box with no leftovers back to his home. Years passed by and on the day of Come Eat With Me [performance] when the audience was encouraged to speak about any intersecting memories of caste and food, this particular memory started to wobble from my subconscious and structured itself to share it with the audience, feel vulnerable, and heal from the shame it has been carrying all while.

On all four days of the show which I was part of, there were so many beautiful and colourful foods brought by the audience—roasted beef, pork dal, mutton kebabs, chicken biryani, cakes, sweets, desserts, etc.—and I happily tasted all, treating the after-show food like a buffet thing. On the second day, someone brought roast beef from a Kerala home. I love it so much, but by the time I got my plate to eat, the portions were over and I was feeling bad. Someone told me, “I’ve some on my plate,” and I immediately grabbed it. She was about to tell me that she didn’t touch them so that I could have them. But there was no need as later we smiled at the freedom that we could share from each other’s plates. This felt like the community Come Eat With Me wants to so urgently provoke: to create this space to inter-dine, mingle and destroy the boundaries inflicted by the caste society.

Can you tell me more about the deconstruction of food, like deconstructing the memory or the experience of food?

Vamsi: When I talk about chicken curry, I talk about its ingredients. The recipe is not that important anymore but its ingredient—the poppy seeds and the chilli powder—are just two things and the stories around it are important. I’m not even talking about the chicken so I’m sort of deconstructing the food. I’m again reconstructing the idea of that food. So in this way, I’m deconstructing this and reconstructing that…

Harsha: In the programme, one guy was asking: why aren’t you serving beef? You simply responded to him saying I grew up eating this, this is my memory, this is my tribute and I’m going to cook it. But I felt like in a way you also have to fight this; what partly feels like a kind of Savarna gaze. It is as though Dalit food means they are expecting only beef or the innards of animals. This also feels like a colonial gaze where they are trying to define and want to see such-and-such only as Dalit food.

Vamsi: They are trying to homogenise. They want to see it as “this is what ‘they’ eat”. My fight is about that homogenisation. I want to break it. I’ll tell you about chicken curry and that it is a broiler chicken – not even a country chicken! And wherever we are coming from, how we grew up, what is our upbringing, what are the possibilities we have, why am I not talking about mutton? It is just because of our financial and economic decisions that chicken has become an important staple.

Harsha: We were talking about mobility to cities and how after intermingling with the people in Savarna households around, we try to avoid the shame that some of our earlier recipes carry. So chicken curry becomes another kind of window where Mom would assertively choose to put poppy seed paste instead of cashew nuts. Poppy seed is thus the trace that remains in her recipe which has survived through memory and the censuring gaze of the caste society. I think this is the story of that poppy seed as a trace, as a larger story of that Dalit woman. Rajyashri Goody also says that we are vegetarians but it’s about how even these foods have meanings of shame attached to them. Talking about these traces and constructing them as Dalit food is the larger project. To not at all talk about just Dalit food but everything around it.

Vamsi: Even though I [refer to] the relationship between caste and food, I talk very little about food. I talk more about things intersecting food and caste. I dupe my audience in that way.

Harsha: It’s such a tease to say we are going to talk about food. To use food as a device to bring in the larger monster from the backdoor, i.e. caste, the experiences of shame, pollution, discrimination, etc. Lastly, How does Come Eat With Me address the intersectionality between caste and gender?

Vamsi: When we are talking about food, the stories are mostly about Dalit women. So what does it mean that a man like me is telling these stories? It is definitely skewed toward my gender as a man having his own privilege. But my own contextualisation, my own set of struggles, and my own memories put me at ease to tell these stories. Bringing stories of Dalit women who have become formative to my identity as a Dalit and recapitulating and reclaiming that practice in itself becomes intersectional for me.

Harsha: One of the friends who attended the performance was saying how you reminded them of Nora Samaran who writes on how men can reverse patriarchal cultures by learning and imbuing values of nurturance and care. This is interesting because of how a Dalit woman (or a Dalit working woman actually) raised us and how the men of the household got to think about food or waste or organise whatever it was that constituted the kitchen. Since our childhood, she would be hell-bent on us picking up our leftovers, throwing them in the dustbin, and putting the plates in the sink.

Vamsi: An educator indeed in running the household. I mean I don’t mean to say that it is also a job of a woman to teach.

Harsha: Yeah but it is also striking as we are talking about Nora and how she writes that men can learn with women instead of other men. So the household [our mother is] coming from, her father or elder brother, these men, like most men, don’t pick up their plates, don’t pick up their leftover waste, and when we go to their houses and see this, it gets very uncomfortable. At the back of my mind, I realise, since her passing, there has always been this obsession to set up things like her, being neat like her. You also feel like you want to cook like her. Ammulu gaari kodi kura is indeed a construct born out of her memory, your passion and your obsession to reconstruct it. I think this is a different articulation altogether. Now, this is becoming a larger discussion on how a Dalit woman and her impressions have kind of initiated so many things. Her [imprint] has initiated the memory in you, the practice in you. This also kind of brings back the question of how do aesthetics learned from a Dalit Bahujan kitchen follow through in the aesthetics of the performance. How did she organise the household by organising the men in the household? I think this is a powerful thing to look at how the idea of a Dalit kitchen or a household itself originates. These experiences are important.

Vamsi: We are looking at this in retrospect but what does organising these three men in the household means for the larger discourse around Brahmanical patriarchy and Dalit feminism?

Harsha: I’m really quite intrigued by this intersection, how it is different for the upper-caste women and working women of the Dalit Bahujan communities. We all say that Dalit men also enable patriarchy. But our mother Chandrakala’s story kind of stands out for me, in the sense that from the kind of patriarchal household she comes from, when she enters a new household after getting married, there are three men in her life again. I think here she fights back—in the kitchen and at the dining table—one microcosm where caste and patriarchy operate. This we are indeed looking at in retrospect, an articulative construction of how the kitchen and dining spaces are being subverted and how Dalit men are being shaped, pushed and provoked to partake in these spaces—the spirit Come Eat With Me imbues and ignites, among so many other things it wishes to say as a whole.