“How to ask a woman whether she has been called a daayan?”

This was the first question that came to the minds of 46 women who were assigned the task of surveying those who have been victims of witch-hunting in Bihar. In the state of Bihar, as in Assam, Chattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha, witch-hunting is an open secret. In villages where witch-hunting incidents occur, some are perpetrators, while most are complicit as silent bystanders. The violence is a direct consequence of the silence and the agreements hidden within it.

If naming or calling a woman ‘daayan’ is considered as much an act of violence as the atrocities meted out to her — for example, parading her naked and forcing her to drink urine — then how can a feminist researcher begin her line of questioning without repeating that act of violence? For these 46 women (and the collectives they are members of), the purpose of the survey was restoring the dignity of the victims of witch-hunting and those facing witchcraft accusations through state advocacy, while using the findings of this survey as evidence.

This story could begin in 2023: A high number of cases of witch-hunting started appearing in the records of Nari Adalats in Bihar. But, the story of Nari Adalats is incomplete without the story of the Mahila Samakhya Federations in Bihar, which again is incomplete without the story of Mahila Samakhya Programme. So let’s start from the beginning, because a) The surveyor is as important as the surveyed, and b) A little feminist history hurts no one.

***

In 1986, a landmark educational policy was designed (and subsequently revised in 1992), called the National Policy for Education. What was landmark about it was its recognition that the empowerment of women is a precondition for their active participation in education. This may seem simple today but until this point, the focus had been on ‘delivering’ development to women as if they were receivers or passive beneficiaries, rather than redressing gender imbalance.

While education’s ability to empower women was seen as an outcome, empowerment as a prerequisite to accessing meaningful education was the new and radical idea.

This led to a Programme of Action (PoA) in 1992 which laid down ‘enhancing self-esteem and self-confidence’ as the first parameter amongst the many that informed the Mahila Samakhya (MS) [Education for Women’s Equality] Programme. MS Programme was built on the links between empowerment, learning, and literacy in a way that all three weren’t equated with each other; rather each factor created the circumstances for the other two to happen.

This led to good ol’ grassroots mobilisation that, over a decade, grew into Mahila Sanghas or Federations. Women — predominantly from SC/ST, Muslim, and backward communities — who were landless and engaged in wage labour, came together to discuss, reflect and act upon their issues of access, entitlements and rights. The Mahila Federations were registered as autonomous societies on the state level and this programme was implemented from 1989 to 2016.

As MS prioritised the idea that rights-based education encompasses the knowledge of one’s place in the world, Mahila Sanghas grew into incubating and holding alternative structures like Nari Adalats (for issues of violence against women), Mahila Shikshan Kendras (Adult Literacy Centres) and Nari Sanjivani Kendras (Health Centres). During this time, many NGOs supported the work of the Federations in different ways. Nirantar Trust was registered in 1994 and it collaborated with the Federations of Uttar Pradesh to design residential education programmes for rural women and girls, as well as developing ongoing education/skilling initiatives and designing curricula.

But all good things come to an end, and the exceptional MS Programme was, alas, no exception. In 2016, the Government of India ceased funding of the 26-year old programme with 2,000 staff members (despite the 1 lakh postcards that rural women in Bihar sent to the Prime Minister’s office). With no support from the central government, the Sanghas/Federations had to stall their institution-building and capacity-strengthening work. This is when Nirantar, along with other NGOs, decided to intervene and help build strategic alliances of the different federations with other stakeholders like Best Practices Foundation in Karnataka, Bhumika Women’s Collective in Telangana and Solidarity Foundation in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

In November 2022, Nirantar Trust had invited Vanangana, a rural community-based women’s rights collective located in Bundelkhand, to do a training of the Federation members on casework and what it means to work with survivors of gender-based violence in rural areas. While they were in the training, they heard that a woman had been stripped and burnt alive by villagers in Pachamba, a village located in Dumariya block of Gaya district. It was also discovered that the victim had previously submitted an FIR at the nearest police station against her accusers, following which no action had been taken. This news, which has still not made it to national news media, became the trigger for the witch-hunting survey. Soon, the Federation members working in Nari Adalats pulled out case records and saw that witch-hunting cases had seen a steady and alarming increase. The members of the Federation intended to investigate this further and wanted more contemporary data on the nature of such violence. Nirantar brought together other NGOs like IZAD, Parivartan Vikas, and Bihar Legal Network and conducted several meetings with the Federation members on how a survey instrument can be designed to conduct this study with the survivors.

***

Everyone in these villages (majorly located in the divisions of Patna, Magadh, and Tirhut), which included the Federation members, knew about daayan hinsa. When she was a child in Champaran, Laxmi’s younger brother had died, for which her mother blamed an old single woman in the neighbourhood, accusing her of witchcraft. Premshila, born in Kolkata, had never heard of daayan but after her marriage in 9th grade, she shifted to Bihar and heard the term for the first time when her mother-in-law accused an old woman of troubling her family with black magic. This word, sooner or later, became a part of the lives of all Federation women who intervened in cases of violence against women, which often manifested as witch-hunting.

Since the Federation women were also leaders and mobilisers of women’s collectives in different villages, they also heard whispers of someone within the group being considered a witch.

Hence, they began taking countermeasures. When Sangita started leading a women’s collective in Gaya, she made sure that the box containing teaching materials and books for the Jag Jagi Kendra (which runs bridge courses for dropout girls) was kept in the house of a woman who was accused of being a daayan. One day, the woman who ran the Jag Jagi Kendra requested Sangita that the box be shifted because, ‘girls don’t like to collect their books from that house’. Sangita, who was nine months pregnant at the time, went to the house herself — despite everyone’s apprehensions — to retrieve the box. She did so in order to further assert that there was nothing wrong with the house or the woman, and it was unacceptable to say that girls don’t ‘like’ to go to a particular house. Even Laxmi, after she was elected as a leader in 2016, especially insisted that women who were alienated by others for being a daayan, be made a part of the collective’s meetings and that everybody drinks water touched by their hands.

In fact, the Federation members were at the forefront of battling this kind of gender-based violence. Jasuda recounted how, a couple of years ago, four young men died in the Gaighat block near Patna in the course of one year. Due to this, rumours started flying that a daayan was doing this: “Why else would only young men drop like flies and not children or senior citizens or any other group of people?” Jasuda was told by the Federation member from Gaighat (let’s call her G) that a man belonging to a dominant caste was actively spreading these rumours. In fact, earlier, he had unsuccessfully tried to make sexual advances towards one of the four young women married to the now-dead men.

G was convinced that the rumour and the accusation was essentially a revenge for thwarted desire.

This man collected money (Rs. 1,80,000) from each and every household, across different caste groups, and used Rs. 1,00,000 to invite an ojha (exorcist) from Jharkhand to find the witch. A mela (fair) was organised. The mood was celebratory. Extended families came in from other villages a night before the mela. “Kal yahaan se daayan nikalne waali hai (a witch is going to be revealed tomorrow)”.

The plan was that the ojha would strain rice, which would be eaten by all the women in the village. The woman who was unable to eat it would be declared a daayan. G raised her voice against it and demanded that the men eat the rice too, and there was no way only women were going to eat it. This led to stone-pelting on G’s house, which went on for the entire night. After hearing this, Jasuda and 8-9 other Federation members went to Gaighat, pretending to be sick women needing to see the ojha. On reaching Gaighat, they first went to the police station to notify them of the upcoming mela. But the station was pelted too, and four police officers were wounded.

Those who managed to sleep on this night, woke up on the morning of the mela to the news that the ojha had fled, and so had their precious crowd-fund. Angry at the bag waali mahilaayein (‘women with bags’ aka the Federation members) who they believed had scared off the much-awaited ojha, 1,000 men surrounded 8-10 Federation women, demanding their money back. A politician amongst them swore that he would withdraw from the election if he did not put all Federation women behind bars, leading to a huge round of applause.

As she was narrating this, Jasuda smiled and revealed that the next person who spoke was a legislator who thanked the women for saving the village from the conflict and violence that would have occurred if the ojha had accused a woman of witchcraft. The politician threatened the legislator with violence and the tension increased. When we asked Jasuda what happened next, she said, “Finally, the members of the administration organised an impromptu magic show for the village and thus it all ended — at least for that day.”

But despite the history of Federation women standing up against violence, there was tension within the ranks when a research survey on witch-hunting was proposed.

“How will we go and ask a woman if she has been called a daayan?”

“Wouldn’t that lead to further hostility from her and her family?”

“What if she asks us the name of the person who told us that she is a daayan?”

“More importantly, wouldn’t that itself be an accusation and an attempt to malign someone’s identity?”

These were some of their questions. Earlier, the plan was to do a block-level meeting across federations, followed by village-level meetings involving representatives of the respective Panchayats. But, the Federation members knew that both perpetrators and survivors of witch-hunting would not express or confess in a public meeting.

The rumours of a woman practicing witchcraft are almost always spread behind her back as gossip, and since it is a matter of public humiliation, it demands a lot from the survivor to express this in an official meeting.

Finally, they tried another strategy. They conducted a smaller meeting amongst themselves… Here, many women shared that they knew of women in their villages who were humiliated and accused of being a daayan. One woman shared that her mother underwent the same. Another shared that her marital family had committed violence against a woman in their neighbourhood in the name of witch-hunting, and that she did not know how to go against her family in order to stand up for the woman. There were also a few women who went ahead and shared that they had been called a daayan themselves. For the time being, the Federation office became a ‘safe space’ not only for survivors, but also silent bystanders who were able to confess their own guilt at being silent when these accusations were made around them, by people they knew really well.

It was at the end of this meeting that the Federation leaders decided that only those women will be surveyed who choose to bring up their experiences on their own, without any suggestion or provocation by the surveyor. The script was simple: the surveyor, who now has a list of women accused of witchcraft, will knock on the woman’s door and introduce herself first. Then, she will start talking about how the Federation works against gender-based violence, mentioning witch-hunting along with dowry deaths and marital violence. If the survivor herself intervenes and shares that she has also been called a daayan, the surveyor will introduce the survey and its objectives. After sharing this, the surveyor will request consent and promise anonymity, if that is a concern for the survivor. Finally, the surveyor will begin asking questions.

Not all conversations reached this point though. For example, Laxmi shared that several women who agreed and consented to the survey didn’t get to be a part of it because their husbands or sons were adamant that the women won’t talk. Despite promises of anonymity, they feared further humiliation and the possible revival of a painful rumour that may have now become dormant.

Despite this fear, 145 women in 118 villages across 10 districts consented to participate in the survey and agreed to share the painful experiences of being declared a daayan.

Each conversation for the survey took more than two hours to complete. Since the surveyors were women from the same geographical and social location, the survivors found a connection with them; the surveyors shared that many survivors cried while they were sharing. Often an entire afternoon would pass in one conversation, and the surveyor would leave to walk towards her house after a second cup of tea was served in the evening.

Jasuda shared that when she went to a neighbouring village for a meeting regarding the survey, she happened to ask a woman for help in finding the house of the survivor of violence due to witch-hunting. The woman (let’s call her A) exclaimed, “Baap re baap, hum nahi ja sakte hain. Aap chale jayiye. Hum nahi jayenge (There is no way I can go there. You go ahead. I will not go).” When Jasuda inquired further, A warned that something bad will happen to her if she goes near that house. Jasuda nonetheless took directions and went ahead. She found an old woman (let’s call her B) at the house and, after the above-mentioned procedure, drank the water offered by B and started asking the questions for the survey. B, as she was sharing her experience of exclusion and alienation from the social life of the village, started weeping, expressing gratitude to Jasuda for sitting patiently and listening to her. As they were sipping tea and conversing, Jasuda saw A lurking outside the house, eavesdropping on them. Jasuda invited A into B’s house and made her sit with the two of them. It was then revealed that the rumour of B practicing black magic started in A’s house almost two decades ago, hence A’s nervousness against what B might share with Jasuda. With Jasuda in front of her and A beside her, B complained that she was hurt by how A excluded her from all the feasts in her house. A accepted that she kept her out, but put up the defence that she was also under immense pressure from society and excluded B due to fear rather than ill-will. She was afraid that if she invited B to a feast, the others in the village would either not come, or accuse her of being a witch like B. B heard A’s defence, wept, and responded, “No, you are saying that you were made to do it, but you by yourself have said enough things to me as well.” A agreed and apologised. Jasuda explained how witch-hunting is an act of violence in the guise of a superstition and informed them about the legal safeguards that women can use to fight against this practice. She left the house. One survey form was filled.

Sangita narrated the story of T, whose husband died 2 years ago. Sangita knew that her entire marital family blamed her for his death and accused her of witchcraft.

T shared that, as she had been accused and abused for so long, she sometimes doubted herself and wondered if she really was a witch.

In fact, T had gone to the ojha on her own, to get ‘cured’. She pleaded to Sangita that she really had no clue how she got cursed and by whom. She said that the ojha told her that someone had placed something on her eyelids that made her a witch, and now she does not know how to get rid of it. Sangita argued with T and asked her, “If you had gotten this power, wouldn’t you have stopped your husband from dying?” and tried to convince T that she must not believe in any of this. T was not entirely convinced. “I don’t know anything. All I know is that these misfortunes end up happening to me. A goat belonging to my family died recently and my mother-in-law blamed me for something I said on the day the goat died. So, I sometimes feel I am cursed with some power.”

The ‘misfortune’ is never interpreted as the vulnerability caused by an inefficient healthcare system or the consistent and long-term effects of socio-economic marginalisation. As suggested in a similar study done in Assam in Goalpara and Sonitpur districts called “Witch-Hunting in Assam: Individual, Structural and Legal Dimension”, illness or death of a human or an animal is the most frequent trigger for an accusation of witchcraft.

The misfortune becomes directed at a body; an already marginalised woman is abused day-after-day and made to feel that she is the reason for death. Crumbling medical infrastructure, facilities and staff in Bihar’s hospitals or the sheer lack of clean drinking water and food rarely feature as the reason for loss of life.

***

When we asked Jasuda if something changed for any survivor after the survey, she shared the story of M.

M’s brother-in-law’s child was bitten by a dog and despite being told to get the child to a doctor, they took him to an ojha (witch doctor). Six months later, the child died and M was blamed for the death. This led to her being beaten up by her own family members. M was excluded and humiliated by other villagers too; the neighbouring women started hiding their infants’ faces from M so that her nazar (gaze; this word is often used to signify a gaze of envy, implying black magic) would not fall on their children. When M asked how she could prove herself innocent, she was told that she must go to the Thawe Mandir in the Gopalganj district of Bihar. As she did not have the money to commute to Gopalganj, she and her husband were made to sell the bicycle that her husband used to ride to work, in order to obtain travel money to go to the Mandir. When the Federation members first learnt about her case (before the survey), she did not want to file an FIR or involve the Panchayat, in order to avoid further defamation. They tried to support her through counselling and later reached out for the survey. After the survey, Jasuda got a call from M.

M was again being accused of witchcraft by a man who lived nearby. She wanted to file an FIR now. When the man found out about this potential FIR, he apologised to M and was made to sign an agreement paper promising that he won’t repeat this again. M finally said,

“If someone calls me a daayan now, I am not selling my bicycle. I am going to take them to court.”

***

Bihar was the first state to introduce the act against witch-hunting, the Bihar Prevention of Witch (Dayan) Practices Act in 1999. Five other states followed. The purpose of the law was for the state to be able to punish someone and take preventive action against the perpetrator for identifying a woman as a daayan. And yet, as the research study conducted in Assam cited above shows, the police only intervene (if at all) when the violence reaches a critically high threshold. The special law has failed because the desire to commit violence against a woman accused of witch-craft is deeply rooted in the public psyche and a mere law cannot make a dent in this psychopathy. As with lynching laws, it is hard to criminalise the actions of an entire village and make the entire society accountable. Unlike domestic violence and sexual assault, where private individuals can be held accountable, the public gaze is responsible for this form of gender-based violence. How does one punish a gaze?

Witchcraft accusations, once made, lead to multiple forms of violence (dislocation, assault, public humiliation and boycott) that destroy a woman’s world irreparably. This study as well as others indicate that criminal law remedies will not make a dent in the public impunity attached to witch-hunting, or touch the lives of women. The Bihar survey demonstrates the importance of local authorities (such as Mahila Samakhya Federations in Bihar) who have ensured cooperation between the state agencies and the community, and enforced accountability from the police. We all know that the law has failed, but these feminist grassroots’ collectives of women have shown us that the reason for its failure is that the survivors have not been heard yet. Regardless of whether convictions happen under this law, justice will not prevail until the survivors of witch-hunting remain alienated and unheard. When the crime is a dehumanising gaze, justice is about deep listening, which is something all these surveyors have done in the process of conducting this research.

We would like to credit the study “Witch-Hunting in Assam: Individual, Structural and Legal Dimensions”, which was published in 2014 and is the outcome of the collaborative effort by Partners for Law and Development (PLD), Assam Mahila Samata Society (AMSS) and the North East Network (NEN). This report has been critical in the writing of this piece and will be insightful for anyone who is interested in reading further.

Findings of the Survey

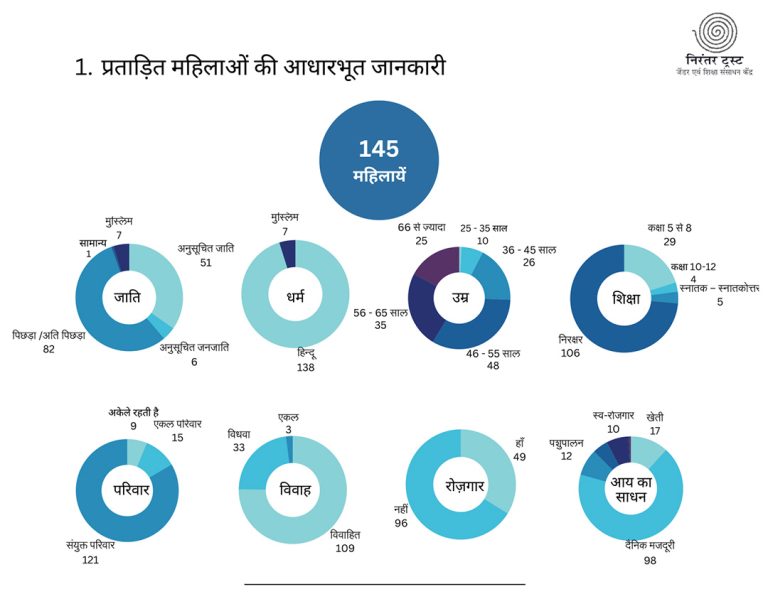

The surveyors from Bihar Federations were looking to survey women who have been accused of witchcraft. At the end of three months, 46 women (Federation members) surveyed 145 women in 110 villages located in seven districts of Bihar.

Here is a link to the survey report.

Profile

- Out of the 145 survivors, only 1 woman belonged to the general category. Most women (56%) were either from Backward Classes (BC) or Extremely Backward Classes (EBC) and 39% of the women belonged to SC and ST communities. The surveyors told us again and again that nobody has the gall to accuse a woman belonging to a dominant caste of witchcraft.

- Most of the women (74%) who were surveyed were above the age of 45 and a significant percentage (41%) of women were above the age of 55.

- Most of the women who were surveyed were illiterate (73%) and employed in daily wage labour (67%).

Thus, it is clear that an illiterate, landless, and daily wager women above the age of 45 can be easily accused of witchcraft by those around her. In conversations with the surveyors, they also revealed that a woman who engages in many religious activities (“pooja-paath”), can be considered a witch. A similar study done in Assam (mentioned above) also suggests that often extreme religiosity, difference in religious practices (in the case of inter-faith marriages for example), any novel ritual practice, et cetera are read as signs of witchcraft and may be treated as evidence to support the labelling.

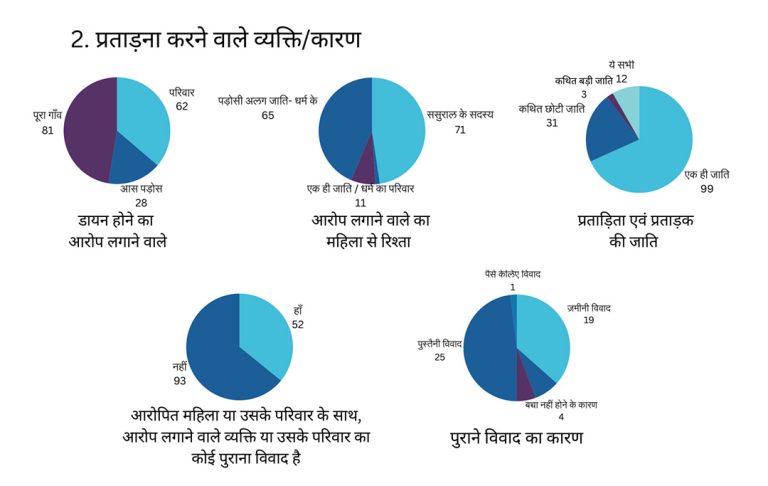

Profile of Accuser

As most women were married (75%) and living in a family set-up (83%), it is clear that the institutions of marriage and family were unable to protect them from this accusation. In fact, for almost half of them (48%), the members of their marital family were the ones that accused them. For 68% of the survivors, the accuser belonged to the same caste as that of the survivor. This shows that witch-hunting is not about superstition as much as it is a means to deal with intra-community and intra-family politics. A similar study done in Assam (referred to in detail below) suggests that even the support of victims’ husbands does not shield them from being targeted.

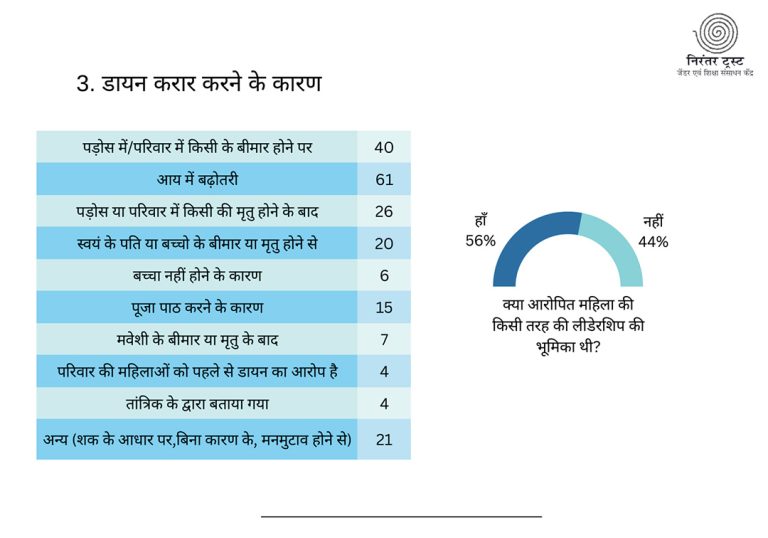

Reasons for the Accusation

56% of the women who were accused of being witches reported that they were in some sort of a leadership role (with the Federations or government schemes such as Jeevika Didi, ASHA, or Anganwaadi Worker or within the Panchayat) when they were accused. 42% of women reported that the increase in their income was the reason they were accused of witchcraft. This is an important number because it tells us that we need to stop looking at witch-hunting from the lens of superstition, and instead use the feminist lens, which forces us to look at power and how gender-based violence is often the patriarchy’s response to anyone who dares to wield power against norms. Thus, witch-hunting is also a way to curb women’s mobility and ensure that they remain docile and vulnerable, since a woman’s upward mobility is considered a threat to the patriarchal structure.

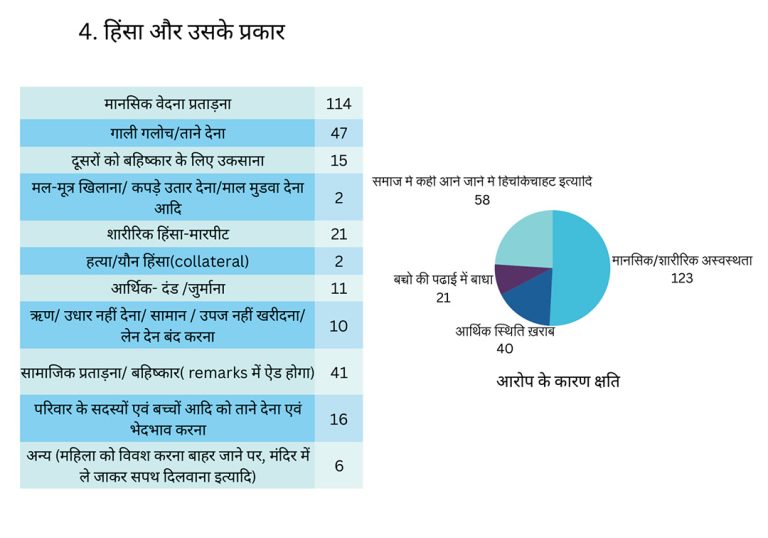

Forms of Violence

The women have reported that multiple forms of violence were done against them as a result of the accusation of being a witch. Most women (78%) reported of mental torture. 32% of women reported verbal harassment and humiliation and 28% of the women reported social boycott by members of the village. As a result, 84% of the women said that their health (both mental and physical) has suffered since the accusation. Several women have also started believing that they are witches and are either giving whatever little money they have to ojhas to help them get rid of it, or living a life of constant alienation and daily humiliation.

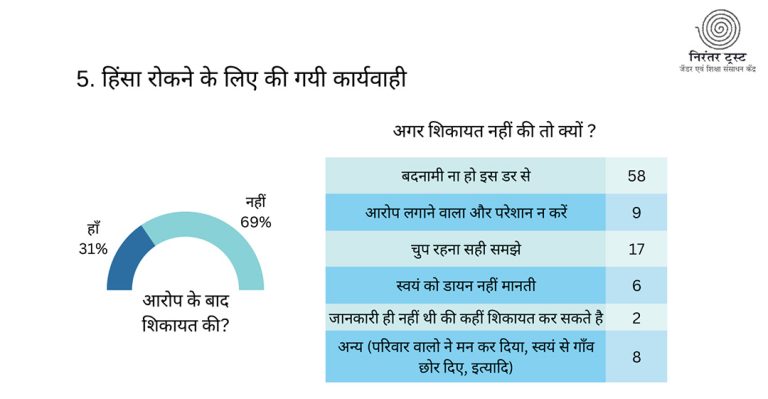

Investigation done to stop Violence

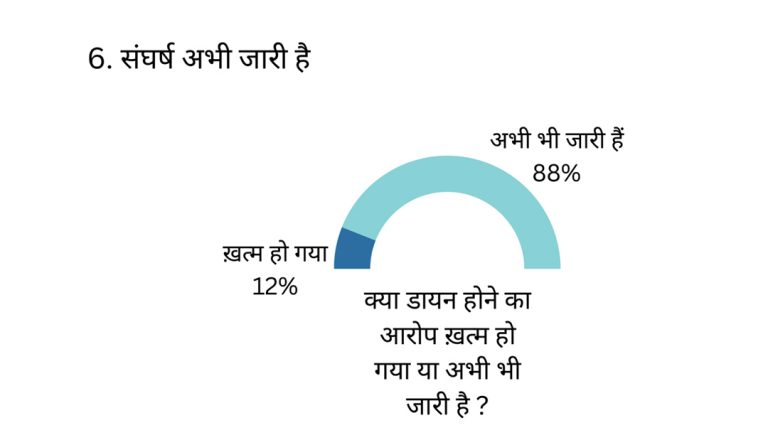

Present Status

List of Bihar Federations that conducted the survey along with Nirantar

- Jyoti Mahila Samakhya, Muzaffarpur

- Swadha Mahila Samakhya, West Champaran

- Shrishti Mahila Samakhya, Sheohar

- Pragati Ek Prayas, Sitamarhi

- Smriddhi Sansthan, Rohtas

- Deepmala Sansthan, Kaimur

- Hamari Drishti, Gaya

Organisations that supported the survey

Juhi is a writer and a researcher who writes long form pieces, provides editorial support, and produces podcast episodes and audio pieces for The Third Eye’s podcast channel Nirantar Radio.

Santosh SharmaSantosh has nearly three decades of experience working with women’s groups in the tribal pockets of Rajasthan and Bihar (Jharkhand). She has helped build capabilities of the women’s groups in organising their microfinance business, availing livelihood support from commercial banks, and the government, and also accessing their due entitlements from the state. She was the National Consultant for the Mahila Samakhya Programme, GoI’s flag-ship programme on women’s empowerment through education. Currently, at Nirantar, Santosh is a Senior Facilitator, anchoring institutional strengthening of women’s federations in Bihar. She holds a Master’s degree in Political Science from University of Rajasthan.