As far back as I can remember, my two override switches have been between my (seemingly) conflicting desires: to be taken seriously and have a good time. One of my earliest memories is my father telling me bemusedly, “You can’t always be having fun!”

I’ve always been too quick for my own good. Quickly bored1, hyperactive, tapping my feet, restless and loud. My parents had a cheat code — the children’s section at the British Council Library. Once a month, my sister and I would be taken there and set loose. We each got four books to borrow, but I’d pick for both of us, so I got eight.

A quiet, sedate bookworm is one thing. I was a disruptive troublemaker with a reputation (despite my best efforts) for not playing nicely with others. But when I was 14, I fell hard for Political Science in my first week of encountering it. The subject occupied me entirely, and I felt that favouring it made me a serious2, clever person.

14 is also the age when kids graduate from the children’s literature section. For my peers, that seemed to mean Twilight instead of Geronimo Stilton, and for the ambitious, Murakami, crime thrillers and The Secret of the Nagas. I like a good murder mystery as much as the next guy, but I didn’t want to give up on children’s literature.

I wanted dragons, shapeshifting and stories where adults were incompetent and clueless.

I decided on my firm and unwavering allegiance to Science Fiction and Fantasy (SFF, SF or genre fiction). I liked SF. It made me happy.

This wasn’t restricted to reading alone. The summer I was 13, I saw the first three Matrix films over and over again until I knew the dialogue by heart. I grew up on the sci-fi-inspired noise rap ground clipping; I started with Hugo-nominated Splendour and Misery and haven’t stopped listening. A lot of the SF I read when I was younger was character-driven sword and sorcery. Grave, resolute Abhorsen-in-waiting Sabriel standing between the living and the dead. Sir Alanna, the Lioness of Tortall, King’s Champion, Darling Temeraire and Laurence and The Woman Who Rides Like a Man (she always reminded me so much of my mother). I despised His Dark Materials the first time I sped through it at the age of 12, but I’ve loved it so much every time since.

Back in the early 2010s, Delhi bookstores had tiny SF sections that tended to have only American SF. Bahrisons had just four shelves. Landmark in the mall was great because they’d let you read on the beanbags for hours while my sister played on the Wii, but it was a better shout for Fantasy than Sci-fi. We went only to Higginbothams at the airport or the train station, but the selection at the Delhi branch was never as good as the ones at Madras and Bangalore. Crossword’s SFF section was larger but bled into fantasy, even if a surprisingly diverse middle-grade, teen and urban fantasy section. Classic SF, like Douglas Adams and Isaac Asimov, dominated Midland’s two shelves. Fact and Fiction was the only one with a fabulous, varied and Brit-heavy selection, but it closed in 2015. I was very sad about it, and I still dearly miss Uncle Ajit, his lovely little store, beautifully curated window display and excellent recommendations.

The less said about my school library, the better — even if I did cut my teeth on its piles of pulpy fantasy (mostly LOTR derivations featuring clumsy magic systems, flat characterisations and an awkward sexiness) that I’d still power through, out of morbid fascination if nothing else. Amidst this desert, you can imagine my delight when I discovered SFF magazines and websites online that published SFF short stories and novellas — FOR FREE!

[Lightspeed Magazine! Clarkesworld! Beneath Ceaseless Skies! Strange Horizons! Tor.com (now Reactor)! Apex! Interzone! Free SF Online! Science Fiction & Fantasy Forum! SFF Net (now sadly discontinued)! Escape Pod! SFF has been my choice for nearly a decade when reading for pleasure.]

Time travel, instantaneous teleportation, wormhole jumping, generation ships, mind-melding translation, parallel universes, et cetera.

In many ways, the most common devices of SF are about second chances. Who doesn’t want that?

In SF, reader and author match sincerity for sincerity, without artifice. Being a hardcore teenage SF fan taught me so much. It blew my whole world wide open.

Years later, when I was in a position to edit my own SF anthology at Chennai-based indie press Blaft Publications, I wanted to share that with my readers. But I found the shelves of South Asian SF full of repetition and trope-y thrills. Maharajas in space, Ramayana retellings and young adult demigods with the flavour of the Hindu pantheon. The genre and its authors rarely stray from the boundaries and binaries of Amar Chitra Katha comics.

Rakesh Khanna (the editor-in-chief of Blaft) and I set out in April3 2023 to put together The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF — a project born out of our frustration with mainstream South-Asian SF. The more we researched and reached out, the more we realised exactly how new and unprecedented this project was. Despite the long and multivariate history of speculative fiction in India, we soon realised that most published work is still by Anglophone authors who hail from elite backgrounds and write with similar perspectives in mind. While feminist retellings might abound, we found an oversimplification — if not wholesale erasure — of caste within these narratives. It seemed ludicrous.

I get that it's tough to be genuinely original amidst the absolute pits of the Hindu imaginary. But it’s not impossible.

It all started with Ursula Le Guin. Unlike most of her fans, the first time I read her wasn’t The Left-Hand of Darkness; it was her short story Coming of Age in Karhide. While many people were assigned the text in high school, I had no previous context for the physiology of the genetically modified inhabitants of her planet Gethen, whose sexuality was expressed only once a month through a state called kemmer. When in kemmer, they adopt either male or female sexual characteristics, fertility and desire; otherwise, they are non-binary and largely asexual. Coming of Age in Karhide is a low-stakes, character-driven missive set on Gethen, with its eternal winter and none of the novel’s intergalactic consequences. Something about it stuck with me for years until I could access more of Le Guin’s work and see the lucidity, romance and perfect crystalline beauty of her writing and wisdom. There have been criticisms from all quarters — why are allegedly androgynous beings referred to with ‘he’ pronouns? Why does kemmer appear to be a largely heterosexual experience? Not to mention how people seem to think that The Left Hand of Darkness possesses too much interiority and speculative anthropological paraphernalia to be ‘real’ sci-fi, too full of relationships, culture, and sex.

But what about how her writing made me feel? What about where she takes you?

What thrills me about Le Guin’s tremendous body of work is that it is queer writing presented without the shadow of illicitness.

The adventure is more than an academic exercise or voyeuristic thrill; it is a full-bodied story — profound, layered, romantic and full of action. At 15, then 21, and now at 25, reading Le Guin still leaves me ready to take flight. Exultant and giddy.

Rachel Pollack, the legendary author of Unquenchable Fire and the creator of the first ever trans superhero (DC Comics’ gorgeous Coagula of Doom Patrol), wrote in ‘Archetypal Transsexuality’4 that “the word passion originally meant suffering, not pleasure… like that of religious ecstasy, or even orgasm — overwhelming, intense, and ultimately joyous when we surrender to it and let it carry us into the power of the experience.”

***

When I was 21, I lived with three other boys I knew from undergrad, in a little yellow house that now exists only on Google Street View. It was down the road from a branch of the Vancouver Public Library. Since it was tough to access SF growing up, I went all out the minute I got the chance. Intra-library loans and the Libby app became two of my closest friends. I read in my tiny, freezing bedroom. I read between marathon Mario Kart sessions with my roommates. I read on the bus, at the beach, on little grassy knolls dotting my college campus, under trees and in cafes all over the city. It was wonderful. It wasn’t a metaphor for anything; it just was.

In a period of great flux (being 22), reading gave me opportunities to slow down and be entirely captivated. Exposure to such a variety of thought, colour, and character felt transcendental. I had a list (I always have a list) of books and authors I wanted to read — drawn from my explorations, reviewers I liked, and friends I trusted — and I steadily made my way through it. I had the great fortune of developing and enjoying my taste.

So, in recent years, I’ve found that my favourite SF stories all seem to jump headfirst into infernal engines, celebrate wild energy and feature intricate battle sequences and strange abilities with a matter-of-fact glee and brilliant deftness.

I find kinship in how abnormal bodies and deviance can be centred in the genre;

they have shown me worlds I wanted to savour, feelings I wanted to taste, relationships I wanted to experience and people I wanted to be.

The Machineries of Empire by Yoon Ha Lee, Jade Saga by Fonda Lee, and The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison. The sound design of The Green Knight. The Masquerade series by Seth Dickinson, Imperial Radch by Ann Leckie, Aliette de Bodard’s Xuya universe sprawling across millennia, Parimal Shais’ 2019 experimental hip-hop release ‘Kumari Kandam Traps, Vol. 1’. The Texicalaan duology by Arkady Martine. The gorgeously romantic Sorceror Royal by Zen Cho and the spellbinding imagery of The Boy and The Heron. Anything that Becky Chambers writes, the iron and flash of Bladerunner 2 and the explosive drumbeat of Fight Club. Every terrible, wonderful, insane word out of Jounce, the ‘Spirit of Perversion’s’ mouth in Leo Fox’s webcomic ‘BOY ISLAND‘. “I am the part of you that wants to fuck holes and stamp on ants…You could barely look at me in my brilliance. In my teeth, you can see all the machinations of your sorrow.” My awful bright smile.

“…Science fiction critics and reviewers still often treat the story as if it were a mere exposition of ideas, as if the intellectual ‘message’ were all…” said Le Guin in 1994. According to her, “…writers are using language as postmodernists; the critics are decades behind, not even discussing the language, deaf to the implications of the sounds, rhymes, recurrences, patterns — as if text were a mere vehicle for ideas…This is naive. And it totally misses what I love best in the best science fiction, its beauty.”

***

Fiction isn’t supposed to give you answers, but it can provide, if you let it, scaffolding for your morality, life-stuff for your empathy and a shortcut to what brings you joy. Enjoying SF helped me embolden myself and find unacceptable the externally “supplied states of being which are not native to me, such as resignation, despair, self-effacement, depression, self-denial.”

It bothers me so much when people talk about how ‘problematic’ a fictional character is. It is such an intellectually inhibited way of engaging with storytelling, revealing an ungenerous mind and a small, mean heart. It has to stem from some stunted combination of neoliberal identity politics and Hindu ideological purity. Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar read extensively for pleasure, evident from his literary references and wit. Reading is supposed to be fun. There’s no book that you must read. You don’t have to read the entire canon to engage with a genre. You don’t need to read all of an author’s work. You also don’t need an algorithm or newsletter picking for you.

I think it is a crucial part of self-respect to develop good taste.

SF freed me from the despair of the feminine mystique and showed me what I knew had been true this whole time — there absolutely was a better way of relating to other people than playing Bad Things Happen Bingo. It showed me a new way to be. In Sweat and Skin, Lee Mandelo, an SF author and scholar of trans-and-or-queer masculinities, writes that when it comes to literature, he’d “much rather reach for a sweltering, sticky world that’s got room for us all to be strange and vibrant, decadent and industrious, caring and communal”. Before releasing his devastating Southern Gothic T4T horror fiction Summer Sons (not to mention his transition), I knew Mandelo as one of my favourite reviewers on Reactor. I loved his long, detailed textual analysis and how he wrote in his own meanings with close attention. He possessed a genius for making the books he reviewed entirely his own beasts.

“…he had learned the price of the game, which is the peril of losing one’s self, playing away the truth. The longer a man stays in a form not his own, the greater his peril”, warns Le Guin in A Wizard of Earthsea. In-text, this quote is about the dangers that can befall a wizard who stays shape-shifted into an animal form for too long, but it’s hard not to read into the sentence the way I tend to do.

I know my own animal heart.

In his 1986 poem Speculations on a Shirt, Dalit Panther founder Namdeo Dhasal implores readers to “reject the traditional garden of conventions”.

“Let’s change the sex of Eve.

Let’s make Adam pregnant.

Let’s speculate beyond animal anxieties.”

Dhasal, ever relentless, continues,

“And we are afraid of light.

This is how liberation itself punishes a human being.”

The technology of desire shapes us all, either in our pursuit or denial. Although we’re warned so much more often against the opposite, let me tell you as a book-maker, it is a grave mistake to forsake body for mind. I didn’t exactly come of age in a Karhide kemmerhouse. But I’d have liked to.

Dhasal finishes,

“A human being shouldn’t become so spotless.

One should leave a few stains on one’s shirt.

One should carry on oneself a little bit of sin.”

***

“This kind of consciousness can open the door to all sorts of new behaviour. I am struck by how much we talk about rebirthing but never about re-bearing. The word itself is unfamiliar to most people. Yet both women and men are capable of re-bearing…A door opens just by changing the name. We don’t have to be reborn; we can re-bear…” said Le Guin, almost 21 years ago, prescient as ever.

She meant that we all could write new origin stories — christen ourselves into new names and fashion ourselves new bodies, while regenerating our minds and hearts anew.

I see Nabi Haider Ali’s Melonhead, excerpted here, as part of an informal Tamil SF triptych within the collection along with Tamilmagan’s ‘Chlamydom’ (translated by Nirmal Rajagopalan) and Hameedha Khan’s File No. 786 (The Night Journey). They all deal with reshaping the physical form, and myth as science and science as myth, while grappling with the classic SF theme — of the repercussions of who is allowed ‘real’ humanity — in new and fascinating ways.

Is it something you’re born with? Or is it a more profound spiritual choice? What happens when it is denied?

Melonhead is a lively subversion of romance, family dynamics and faith that questions whether being known is being loved. I’ve loved Ali’s gorgeously lush paintings for years, and I’m honoured that he chose to share his writing with us for the anthology. Like me, he knows what it means to transform and is someone whose spirituality intimately informs his artistic process; it was amazing to see a new facet of his storytelling. Set in the small dusty town of Thirukulamandapam, it negotiates what happens after a love marriage and positions the possibilities of modernity against the power offered by the past. What’s scarier, Ali asks: to be haunted by your choices, your faith, or a ghost?

Sociologist and SF author Malka Older points out in Speculative Fictions, Everywhere We Look that so much of the dross and pennants of modern life — strategic plans, political polls, weather forecasts, sports commentary, market predictions, religion, et cetera — are as speculative as their literary counterparts. It should be evident that life as we know it is “built out of speculation and spit”.

In the literary world, people think SF doesn’t matter or isn’t sufficiently complex because it’s about people, ideas and settings that aren’t real. That’s just a matter of temporality. Every day, something living becomes extinct, and every day, new ones are born.

Other people's memories will always be alternate histories.

In her cyberpunk short story collection, Pollack writes, “The magic formula to make someone real is very simple. Trust in their desire. Believe in their passion. This is a true story and a very old one.”

***

The late Telugu literary legend V Chandrashekar Rao, whose character-driven supernatural thriller is featured in The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF, once wrote that he “chose story-writing as the medium to understand life”. He wrote, “Story stood between me and the world and acted as an instructor — it made me wiser. It gave me the eye to look into myself.”

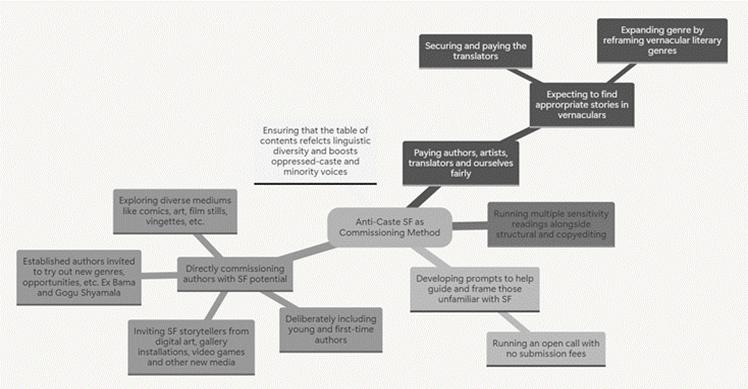

Though I’ve always rejected the superficiality of diversity and rhetoric about representation in my professional and curatorial pursuits, over two years of putting the anthology together, I had to recalculate what I could offer and what I demanded of myself. As I worked, anti-caste speculative fiction became more than a theme within the pages. It acted as a methodology grounding my decisions. Working with such a wide range of authors, artists, filmmakers, scholars, journalists, and other cultural workers made me more certain than ever that we’re not yet at the pinnacle of subaltern culture.

We’re in the sprawling, thicketed middle of a cultural renaissance.

Audre Lorde famously said that the erotic is about encouraging “excellence from ourselves, from our lives, from our work”. It’s about an overwhelming desire to wrestle satisfaction from your labour, starting with your soul. I spent many hot summer afternoons in our dusty distributor’s office in Shahpur Jat in Delhi, running errands and imagining seeing my book on the shelves someday. In Sweat and Skin, Lee Mandelo writes that “culture grows from the organic matter of the arts; the things we make end up making us”. I went into publishing thinking it was the words I loved, but two years in, I realised it was the people. And so this book is borne out of the full-bodied pursuit of beauty and incalculability — worlds within worlds.

Whether it’s a book, a show, a podcast, an essay, an academic course, or even a party, I’ve known for a long time that it is possible to speak with one voice to both artists and audiences, to create a sense of welcome and to open doors. For the last few years, I’ve witnessed the possibilities that can emerge from transient but immutable frameworks of publicly oriented cultural production. So, I hope the anthology’s success functions for all the contributors and readers as a lever with which they can move their worlds.

I don’t expect The Blaft Book of Anti-Caste SF to answer all your questions, fix the world’s problems, or win a Pulitzer — how boring would that be? I hope, however, that it re-bears you, that its living, beating, multi-hearted consciousness mutates you, and that its after-image casts you into light.

1My mother always said that only boring people get bored, which I agree with now.

2It had science in the name!

3Quite appropriately, I thought.

4An essay I have burned into the backs of my eyelids. Read here