The Mind Map accompanies our Travel Log. The Third Eye’s Travel Log programme mentored 13 writers and image-makers from across India’s bylanes to reimagine the idea of the city through a feminist lens.

An artist worked with a fellow to visualise their town, village or city, a ‘map’ of the spaces they actually live in; a combination of their mental, emotional, spiritual and physical landscapes to help us imagine the ‘city’ subjectively.

Srija U is a writer with deep interest in the classroom, queerness, desire and the liminal spaces between all these. She is a former Teaching Fellow at the English Literature department of Ashoka University.

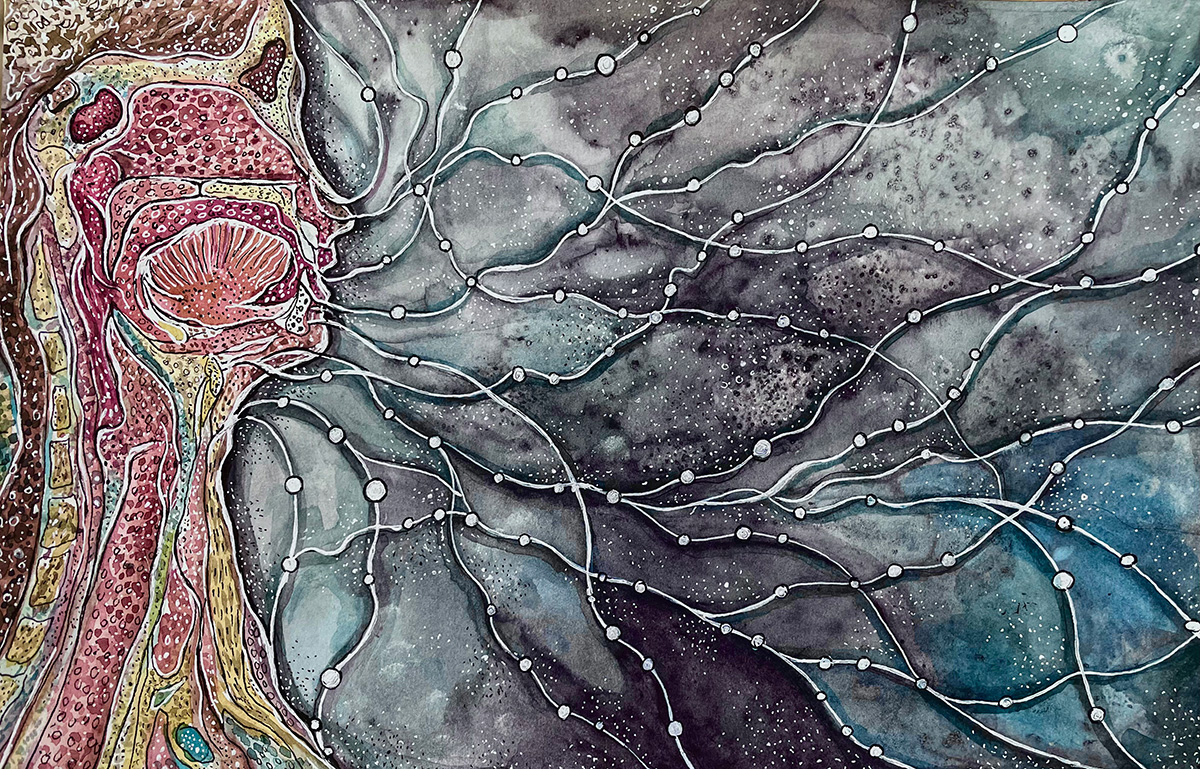

Srija’s Mind Map is imagined by Devika Sundar, an artist who works with art as a restorative, meditative medium, to express collective themes of invisibility, illness, memory and impermanence within personal and shared human experience.

Their mind map is inspired by their shared experiences of pain and bodies, in imagined cities.

Read Srija’s essay here.

When you look at the mind map today, what do you see?

Srija: Lacan, referring to Edgar Allen Poe’s ‘Purloined Letter’, says it’s a letter that never arrives. This mindmap for me induces a similar affect— of a journey that has no destination; one that defers arrival and takes multiple routes.

Devika: For me, this mind map is a search: for language, identity, belonging and connection. For seeking, threading and discovering our own voice.

What do you remember from your first meeting for the mind map? In your first conversation, what did you respond to most in each other?

Srija: We discussed movement, fear of stagnation, unsaid words and forgotten memories.

Devika: We talked of the journey we were both on. Of routes and maps, of jagged cracks and crevices, of broken words and swallowed thoughts, and the honesty, vulnerability and beauty that remained within all of this.

Then going forward, what was the collaboration like?

Devika: Alongside this project, Srija and I formed a personal connection over shared experiences and challenges we both have faced and continue to face with our bodies.

Somewhere, the vulnerability and honesty of these conversations filtered indirectly into the process of this project, by getting to know Srija a little more deeply and understanding the voice, strength and power in her words and thoughts.

Srija: Working with Devika has been an incredible experience.

It’s reminded me that subjectivities, no matter how unique, are perpetually intertwined and interconnected.

Devika and I developed a friendship, one that comes with a certain kind of vulnerability and I’m grateful for it.

If this drawing is about internal cities, what is the nature of her city or where do you locate the city within the artwork?

Devika: I think her city is the one she grapples with both inside and around her. In the artwork, the channels, lines and routes that travel internally within her extend outward, meeting interconnecting points, dots and blueprints found along her journey.

There were two quotes of Srija’s from her essay that really remained with me.

“What language is my desire in and why must it be translated to be heard?”

“The more I rolled my R’s, the further I pushed my mother tongue all the way till the back of my throat until it was nothing but a lump; Every gulp is now a reminder of how the city, an imagined destination, abandons all those who fail to mimic sameness. My difference is what keeps me afloat. I belong elsewhere– a place of no destination.”

Srija, what was your first reaction to the artwork? Did the brainstorming around the artwork also inform your written piece?

Srija: It was a process that went both ways. Devika sent me a rough sketch of her artwork and what I took away from it were the endless channels that didn’t lead to a single place. Often, in creative writing, plot becomes a driving force for stories and lives alike. But I didn’t want to arrive at my narrative from a linear perspective. It wasn’t just a story of movement from the village to the city and in that processing attaining liberation. It was far from that. Devika’s artwork was a reminder to hold onto the differences even if they didn’t make sense in the larger sense of the plot. I wanted markers of the city in the village and vice versa. And the final artwork helped establish that complexity.

How did the City play into the artwork?

Devika:

I wanted to run with the feeling of an “imagined city”, an imagined destination as Srija words it.

There was a sense of creating a surreal, pensive, yet murky atmosphere – contrasting cool blues and foggy greys with deep reds and yellows…

Any tips or thoughts for those struggling to put themselves into the art that they are making?

Devika: To understand the place it’s coming from, I think it helps to identify the larger feelings, imagery, words and thoughts it intuitively stirs within you. It helps me to note these down, before consciously thinking towards a visual or composition.

What’s been your takeaway from the project? Has there been a learning curve from the project that you would carry into your work?

Srija: I’m grateful for Devika’s tender voice and her magnitude of experience when it comes to understanding the body. The project happened at a time when I was struggling to write again, and I’m glad to have taken this up. As someone who’s invested in the space of the classroom, I strongly believe that learning spills into spaces only if we allow it to be uncomfortable, difficult, and therefore complex.

Devika: I feel extremely grateful getting to know Srija, and to have the opportunity to translate her powerful, sensitive, brave and beautiful writing into imagery. I’ve learnt that it isn’t hard to find truth and honesty in each other’s stories, and to derive courage and strength in each other’s journeys.