“You were looking for a woman Zomato worker, and I am not one, so am I still a part of your story?” Bunny asked me a few minutes after coming out to me as a trans man.

I had approached S (now Bunny to me) for this story on how women gig workers are shaping the city with their spatial and social practices. I requested to shadow S, a request that had been met with suspicion with all the women I had spoken to previously. (A woman in her late 20s who used to work on the Rabbit app as an Amazon delivery employee said no because she was in the process of quitting as she was barely getting any packages assigned to her after Diwali. The company had hired more couriers to meet the Diwali rush and the pickings became slim. An Urban Company employee I had spoken to in Dombivli got sick, and was anxious about her identity being disclosed in the process of shadowing.)

S, in Thane, which is my hood so to speak, said yes right away, explaining that taking friends along on the bike has never been an issue.

The next day, I found myself riding pillion on S’s Bajaj Vikrant. The January winter was on the brink of getting colder and the afternoon sweat that we Thanekars are used to hadn’t stained our shirts yet. We first picked an order of two mango ice-creams from Naturals in Manpada and delivered them nearby in Hyde Park. Despite using a motorbike, S had a Cycle ID on Zomato (even though S has been driving motorbikes since eighth grade). I was trying to be a good fly on the wall, balancing between asking questions and keeping quiet. Soon, I realised that I would be left alone with the bike during delivery of orders because buildings with security guards rarely allow such flies inside. That would be my note-taking time then, I told myself. I had assumed that the customer locations would be new to me but maybe not the restaurants. Born and brought up in Thane, I thought I knew my food spots – Vasant Vihar Circle, Hiranandani Meadows Plaza, Amrapali Arcade, the pride of Thane elite – Viviana Mall, and the older and humbler Korum Mall that lies on the same road. During the third order, I was proven wrong as we drove into an unfamiliar narrow street close to Vasant Vihar Circle. Mexibay – Burritos & More was a tiny promising restaurant (not to be found on Google Maps yet) that had apparently lent S a precious carry bag when S had to pick 16 burgers from a restaurant besides the Mexican place. Very quickly, customer locations became the familiar gated communities with their visitor registers, security guards, and lobbies into which S would disappear, leaving me behind with my notebook.

Restaurants, on the other hand, were becoming stranger, almost reduced to kitchens on quiet streets. After a few hours of riding, S asked me if I had a boyfriend. I said I was seeing a trans person. The moment I said “trans”, S recognised it: “Oh, okay yes, trans.”

As we were making conversation at the service yard of Viviana Mall where a bunch of Zomato and Swiggy workers are always waiting to pick up their orders from the food court, I asked S the same question. I like women, said S. I appreciated the honesty and trust that had developed during this ride. While waiting for an order at a restaurant, S started showing me drawings made over the years on their phone gallery. They were of S’s parents and one was of Babasaheb Ambedkar.

Over the course of shadowing S, I could feel the city stretching farther. It was being dragged by the bike to the north towards the massive gated community that is Lodha Amara, with golf carts taking residents to their parking area; to the east towards Lodha Priva with S asking me how to pronounce the name of the building ‘Michelangelo’; to the south near Makhmali Talao (Lake) where the customer had mistakenly written Talao Pali and scared S into wondering if we would have to drive till Thane station; and to the west at Asiatic Enclave where the customer’s voice was unclear on the phone and S was angrily shouting “Hello! Hello! Hello, Sir? Ye- Hello!”

Every time we were at these extremes of Thane West, S, afraid that the next order would take us outside Thane, made sure to submit the partner feedback on the app only after we had driven inwards, hence locating us closer to the central areas. (The next order does not show till the feedback is submitted.) After telling me about wine shops that are open 24/7 and pointing out the spots frequented by the traffic police, we were waiting for an order to be prepared in Charai (an area in the southern Thane West near Makhmali Talao).

One thing in that conversation led to another and S said that they would like to be referred as a man by me. And to call him Bunny. All I remember is that the conversation started with cats, as queer conversations in my life often have.

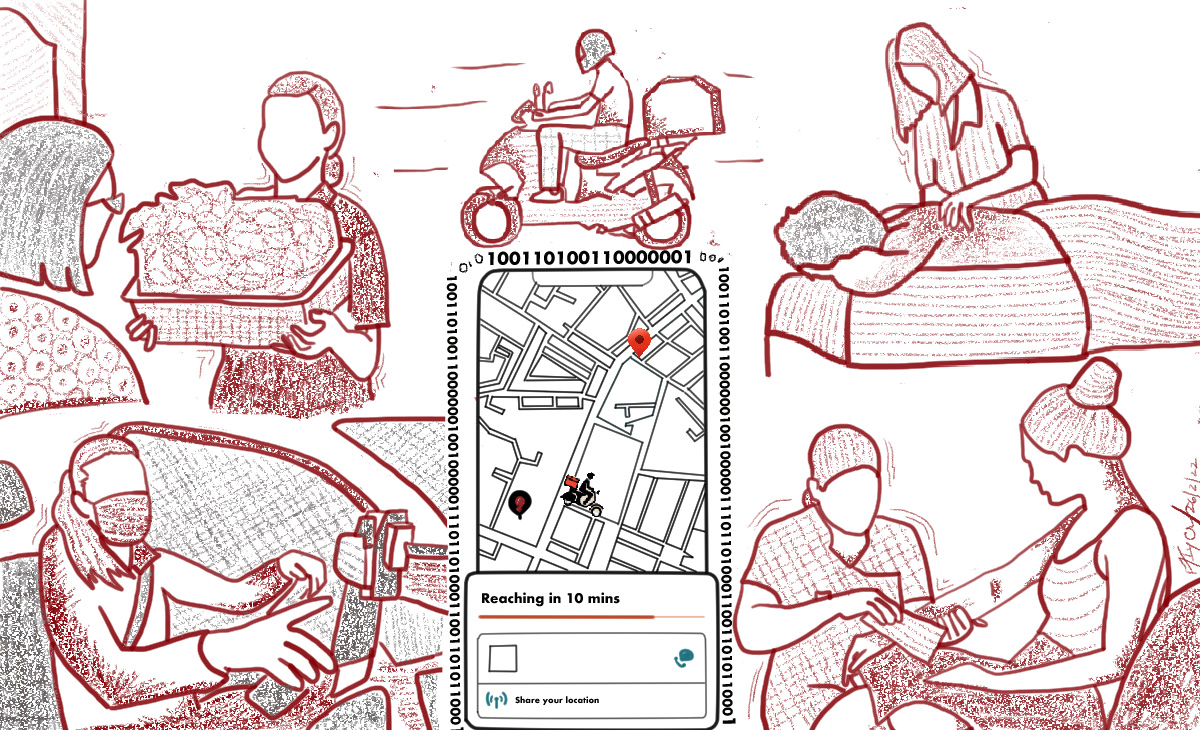

They are at the intersection of public and private space, entrepreneurship and employment, and identity and anonymity. They are ‘partners’ but the company decides their targets, their commission, and their suspension in case of non-compliance. The t-shirts and helmets and the lack of a ‘boss’ lend them anonymity.

But their names on customers’ phones return bits and pieces of their identity back to them. Fairwork India 2021 Report estimated that there are 1.5 million platform workers across 11 most popular platforms in India. There is no gender-aggregated data for the same. A Hindu Business Line report from November 2021 suggests that there are more women on platforms offering salon services as compared to the ones delivering food or parcels. It says that while only 0.5 % of Zomato delivery partners are women, this figure becomes 33% for Urban Company. According to a report released by BetterPlace in 2019, a leading blue-collar recruitment and onboarding firm, the gig economy accounts for more than 1.4 million jobs in India, which include rideshare drivers, delivery workers, beauty and wellness workers, maintenance workers and the like.

Gig work does not naturally lend itself to unionisation as there is no shared space where the partners can organically interact with each other, and the employer is an abstract faceless arrangement of algorithms and technology.

Our story features Prerna*, a 21-year-old woman who worked for Amazon till December 2021, delivering packages throughout the lockdown. Pooja is a 30-year-old woman who partners with Urban Company to deliver beauty services in Gurgaon. Bunny is a 27-year-old who partners with Zomato to deliver food in Thane.

Both Bunny and Prerna got on the platforms soon after the lockdown as it had disrupted their earlier jobs as an educational counsellor and a desk job at a drycleaner, respectively. Soon after, Urban Clap was rebranded as Urban Company, and the cost of products and commission percentage started rising, which then led to protests by the hundreds of beauticians. I met Pooja as she was tripping over an unexpected milestone in her life. The women of Urban Company were coming together for the first time to discuss their problems and initiate talks with the company management, and Pooja was one of them.

Through my interviews with Prerna, Pooja, and Bunny, I realised that their relationship with the city encompasses both the cold algorithm of the platform, as well as the unpredictable attitudes of the numerous people they interact with on a daily basis.

Gig work involving deliveries requires a granular spatial knowledge of the city. A delivery partner does not have the luxury to constantly keep looking at the map for navigation as they have to deliver orders and packages on two-wheelers within a given period of time. Prerna confessed that she had no idea that the neighbourhood of Vasant Vihar in Thane West was this vast before becoming an Amazon delivery partner. Now, she can tell you the location and direction to each and every building in the area. When she had just started, she used to take a long time delivering packages and often ended up being out till 11 pm. But, as she got more familiar with the route, her deliveries got faster.

Bunny has been with Zomato for a short time but his knowledge of the city is like a mind map with many layers. One layer consisting of a clear street map of Thane makes it possible for him to drive to any location without a map. Another layer allows him to dodge the spots frequented by the traffic police (who might stop him for driving without a helmet) along with keeping in mind places where he can smoke in peace between orders. This map also accommodates specific restaurants where he can go if he wants to use the washroom or where he can get snacks and tea, in case he is hungry. He has specific go-to spots in every neighbourhood as he can find himself in any of them at any time of the day. For example, he will eat dal vade at Ajji-cha Vada Pav if he is in Kolbad and have moong bhajji at a corner stall if he is in Devdaya Nagar. Even though he avoids wearing the Zomato shirt as he dislikes its bright red colour, he knows that he will have to put it on before entering the Korum Mall’s service yard as they have strict rules for delivery workers’ uniforms. There is another layer of knowledge that lets him predict where the app will take him next. “Mereko pata hai ki agar main Teen Haath Naake gayi hoon ya Waghle Estate gayi hoon toh 101% mujhe company Mulund hi bhejegi, yeh mereko pata hai. (I know that if I am at Teen Hath Naaka or Waghle Estate, they will 101% send me to Mulund, I know that.”) He considers Vasant Vihar his workplace. No matter where the orders send him, he gravitates back there as soon as food is delivered, unless a new order arrives on the way. In order to not find himself far from home and stuck in Mulund or Bhandup at 11:30 in the night, he must use his knowledge to game the system in his favour.

I was wondering why Bunny refuses to wear a helmet even as he complains of bad driving etiquette of other drivers. When I asked him this, he said, “It’s a hassle to remove it, wear it again, and remove it again.” I didn’t really understand that answer then. But, by the end of the day, I got it. A food delivery partner has to get on and off their vehicle at least 25 times during the workday. It is a labour of repetition.

After all, when an algorithm is your boss, you have got to think like one and algorithmic efficiency dictates that a task should be ideally completed in the least time with the least computational resources. Having repeated the process of delivering orders 25 times every day, Bunny has learnt how to do it efficiently, and efficiency always comes at a cost. The cost for Bunny is the risk of not wearing the helmet.

All three of my interviewees have their own two-wheelers: Prerna and Pooja have scooters and Bunny a motorbike.

Unlike Bunny and Prerna, Pooja does not compulsorily have to travel on her own vehicle to go to customers. But, since Urban Company partners have to carry kits that weigh 15-20 kgs, public transportation is not an option.

“Lots of weird things happen. Someone gets into the auto while you are in it, and sits right next to you without permission. They tease you. I’ve seen a lot of this. Ever since I’ve bought my Scooty, I feel safe. Kyunki meri Scooty hoti hai toh mujhe na koi roknewala hai, na koi mujhe toknewala hai, na mujhe raaste me koi disturb karnewala hai. Kyunki main seedha aayi seedha chali gayi toh koi raaste me kuch nahi bolta… (While I’m on my Scooty neither can anyone stop me, or say anything to me, or disturb me in any way. I come and go as I please.)”

Similarly, for Bunny, the motorbike signified the ability to escape an uncomfortable situation at his own will without having to stop anywhere. “When we use public transport, there is fear. Every girl has that fear. If she is travelling by bus or train, she will be scared. But, if I have my own transport, I will not feel like that because I know that I can leave from anywhere, instantly. I don’t have to stop anywhere.” Public transport then perhaps is not viable for those working on these platforms who expect to travel safely without any stops on their journey, often at late hours of the day.

But it’s not all a smooth ride. Bunny and Pooja have been scolded and shouted at by security guards for parking their vehicles at the wrong place. Pooja has often been asked to leave her vehicle outside the residential society and expected to carry her heavy kit for considerable distances within the building premises.

Having worked as a beautician with Urban Company for three years, she has developed the confidence to speak out against such arbitrary rules. “Main toh bhid jaati hoon. Meri Scooty agar mana kar di ki society me nahi jayegi toh main mana kar deti hoon. ‘Bhai mera bag leke chalo. Lift tak pahucha do. Main Scooty yahi khadi kar doongi. Haan, bag leke chalna padega. Bees kilo ka bag hai. Aap uthao.’ Toh phir majboori mein unko bolna padta hai ki ‘Jaao aap’.

(I start arguing. If my Scooty is not allowed inside the society, I refuse. ‘Sir, take my bag inside. Get it till the lift. I will park the Scooty here. But yes, you will have to carry my bag then. It weighs 20 kilos. You carry it.’ Then, they are forced to let me go.”)

There is certainly a sense of independence and agency that comes with determining one’s own work timings, holidays, and break timings. But this flexibility is often exaggerated. According to a study by the Observer Research Foundation in 2020 on Gender and Gig Economy, such flexibility is less for those whose primary income comes from gig work. For example, Bunny has to stay logged in for 10 hours in order to get Rs. 1400 at the end of a day on weekends. On weekdays, he often is out till midnight, meeting targets so as to have a reasonable income for the day and be able to pay for petrol for the next day. The other trade-off is work security. Since gig workers are paid on the basis of completion of a certain number of tasks or reaching a particular target, their regularity of income is affected on days when work is less. Prerna resigned from her job at Amazon because she was not being called for work for days together. The recent Social Security Code mandates provision of social security benefits to gig workers but it is yet to be implemented.

There is also a feeling of hurt associated with the casteist and classist ways in which they are treated in gated communities.

Both Bunny and Pooja mentioned feeling deeply offended by the separate lifts for service providers in some buildings.

“Mujhe bahut hurt hota hai is cheez se… Aur ko ho na ho par mujhe bahut guilt feel hota hai ki main khud ek society mein rehnewali hoon… aur kehte hain ki servicewale log is lift mein jayenge… Kaam usi se karaana hai… Touch bhi usi ke saath lena hai. ((I get really hurt by this… I don’t know about others but I feel really guilty… Even I live in a housing society, you know… and you tell me to come in the service elevator? You need us to do your work. You need to be touched by us.)

Think about it. They are not letting me go in the same elevator as the other society members, but I am going inside their homes to do their work. That they are fine with. Drinking from the same glass as them is acceptable. But being in the same elevator is not.)” Bunny, pragmatic as ever, also highlights how such discriminatory and unnecessary rules lead to waste of time as they are waiting for one particular lift when three others are already there.

In the same breath, Bunny talks of his fondness for certain buildings in Tulsidham where old songs are played in lifts. He deliberately lingers longer in such lifts just to enjoy the music.

During my time with Bunny, at some point he had delivered an order in Brahmand (a neighbourhood in the northern part of Thane West) and was returning to the bike where I was standing. He had a smile on his face in the 2 pm afternoon heat when he said, “The customer offered me a glass of water!” Then there is Prerna’s experience where the package she had come to deliver was thrown back at her and she was almost slapped by a customer due to an incorrect cash-on-delivery amount mentioned on the Amazon app. Later, she was called in as a complaint was registered against her. She explained herself to her manager and there was no punishment meted out. She was still upset with nothing being done against the customer: “Unke upar bhi unhone yeh (action) lena chahiye. Woh barabar hamara complaint karte hain. Unpe bhi karna chahiye. (Action must be taken against them too. They never fail to complain against us. They should also face the same.”)

As Pooja says, “Kaam sabko chahiye, benefit sabko chahiye. Par kadar kisiko nahi hai. Value kisiko nahi hai. (Everyone wants their work done. Everyone wants to reap the benefits of our service. But, no one holds any regard for us. Nobody values us.) Okay, agreed, you are paying us money. But we are coming from far away, right? Otherwise, to get the same task then you would have to spend on travel, fuel, parking etc.And also time, you’d spend so much more time. If we are saving you all that, I believe some respect should be given.”

(Everyone wants their work done. Everyone wants to reap the benefits of our service. But, no one holds any regard for us. Nobody values us.

There is no value of the person who is giving you their time. Fine, you are paying them. You are doing everything. But that person is coming from far away, right? Otherwise, you would have to go, pay money, and spend on fuel. Your waiting time would also be wasted there and you would also have to pay. All that time has been saved. Everything has been saved. I believe that respect must be given.”)

Pooja also derives a sense of pride and camaraderie from the recently mobilised group of Urban Company partners in Delhi and Gurgaon. She recounted how earlier the women were afraid of each other and used to avoid each other if they crossed paths, scared that the other woman would snitch on her to the company. She mentioned how she recently helped an Urban Company partner who needed help in doing a facial since this was her first gig. “Jabse yeh pradarshan hua hai na, sach mein ladkiyan ek doosre se milti hain na, khushi hoti hai, jahan bhi milti hain ek ghadi baat toh zaroor karti hain milke. ‘Aap group pe ho? Aap kaise ho? Aapka naam kya hai?’ Agar koi ladki kaha kuch laa nahi paayi toh help bhi karti hain.

(Since this protest has happened, when the girls meet they are genuinely happy. They feel good when they meet. Whenever they run into each other, they chat with each other for a bit. ‘Are you in the group? How are you? What’s your name?’ If a girl is unable to get something, they help each other, too.”)

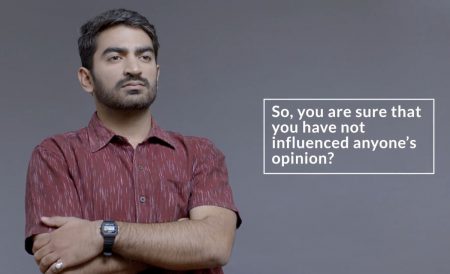

Bunny mentioned that while he desires camaraderie with other fellow Zomato delivery partners and wants to be involved in their conversations, it hasn’t yet happened. When I asked him about mobilisation, he said there are hardly any women Zomato partners in Thane and he does not really interact with the men partners. But, he derives a sense of safety from the symbol of Police on his bike, which has conveniently created a rumour among other Zomato workers that he is a Woman Police Constable (WPC) and works at Zomato part-time. He does not correct them.

When I asked him if he had ordered from Zomato himself, he explained to me that only one restaurant in his neighbourhood has tied up with Zomato. This means that deliveries from other restaurants would charge high delivery fees, making the purchase expensive for him. So he rarely orders from Zomato.

*All names have been changed to protect identity.