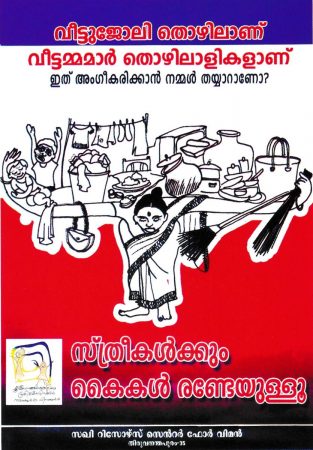

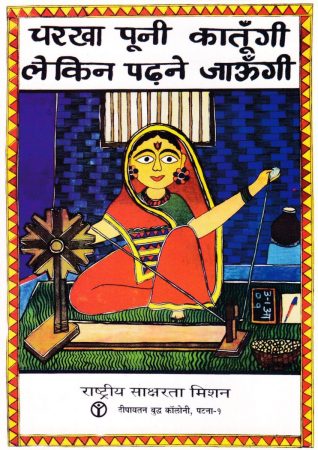

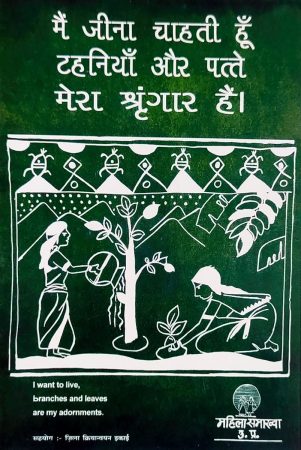

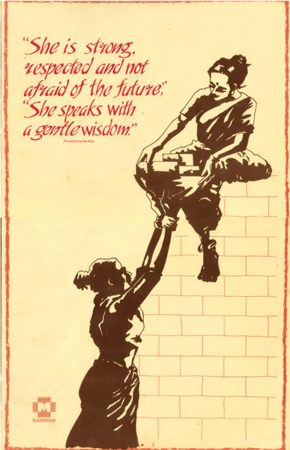

In 2006, Zubaan, a feminist publishing house, started collecting posters from women’s movements across India. These were campaign posters, drawn, designed and printed by women’s groups in villages, towns and cities of an India grasping at, and gasping for, progress.

Today, this is a 1500 image strong visual history of activism, feminism, and the fight for constitutional rights as played out through the rich and complex history of women’s movements in India.

The Third Eye presents a selection from The Poster Women project about women and work. Urvashi Butalia, the founder of Zubaan, looks at the images fourteen years later, and contemplates the meaning of work as a feminist activist, “which is also work, and should be treated like it. It is not a pure thing.”

With inputs by Shamini Kothari.

What do you notice first when you see the posters and their representations of women and work, retrospectively?

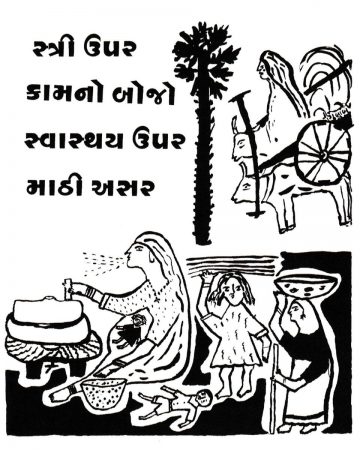

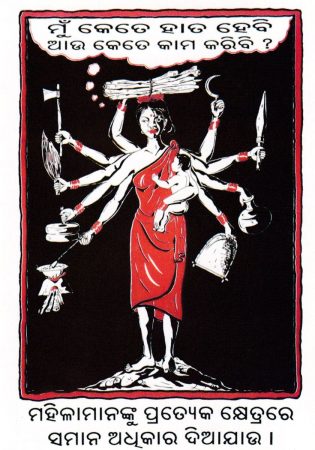

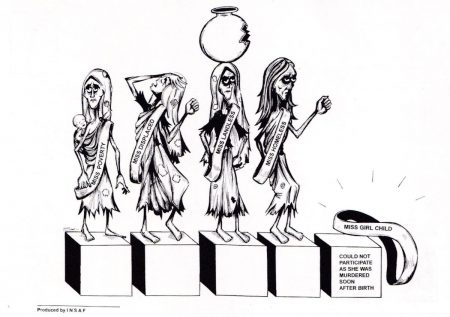

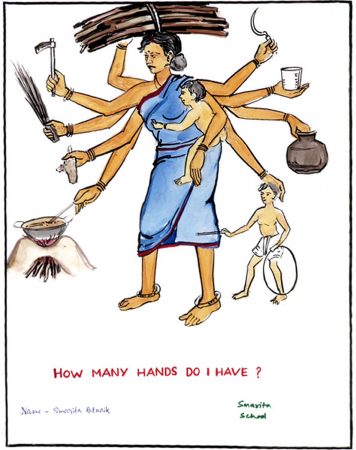

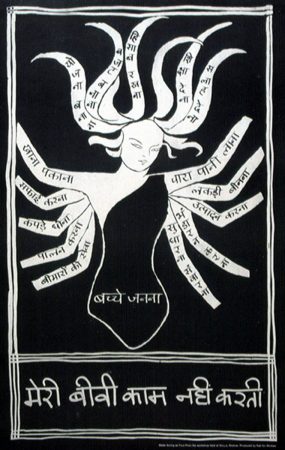

If you were to look at the series of images where the woman has multiple hands, which actually plays upon the image of the many-armed goddess in Hinduism; she holds all kinds of implements of power in her hands, or her arms are cut off, or she is holding various implements of work, mostly domestic. One of those images, which I truly love, is from Kerala. It plays on the image of the goddess in a different way, where the arms are straight out, they hang implements of work, but on one of those arms is a handbag. I love that, because to me, it represents the transition from seeing the woman and her work beyond the domestic sphere. She is stepping out of that space. Of course, at the time it was a very middle class image, and now, not necessarily so. But in a sense, you can already see the shift in those posters and they already date to about forty years ago.

If you had to commission a new set of images around women and work, what do you think would change?

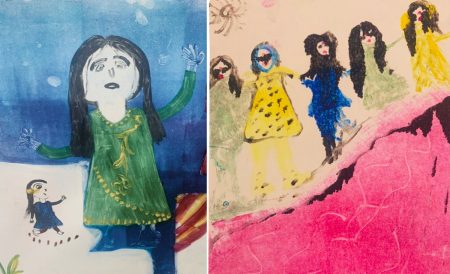

I imagine there would be quite a lot of similarities and quite a lot of differences. In fact, even three to four years after The Poster Women Archive, we collected another set of images. These were not posters, but drawings made by largely rural and tribal women, through the lens of feminist stories that are narrated through a traditional art form. If you look at those, they already show some kind of transformation. For example, a lot of the women, especially the Madhya Pradesh or Chattisgarghi tribal artists, have women dressed in trousers, riding little motorcycles and represent a kind of ‘coming out’ of the home. In that collection, there were also beautiful fabric appliqué work that uses leftover scraps of silk from Bihar, and tells the story of how fisherwomen in Bihar won the right to fish, as opposed to just selling the fish farmed by their men. In that, too, you see a difference in the image of the working woman. There is no change in the traditional dress, but the transition in access into the public world, represented by the sea, one that has been forbidden to them, is made visible.

Actually, the workplace becomes equally important in the engagement with work, and it’s important to map how that changes.

This was realized in the case of Bhanwari Devi, which was a new kind of knowledge that came to the feminist movement, the idea that the workplace can be anywhere; the home, the field, the transition space between the two, and so on.

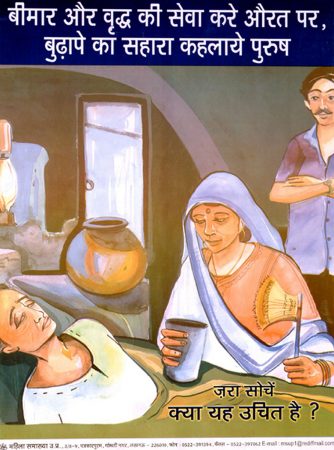

So, looking at these kinds of things and to see how they impact women’s access, opportunity and the work itself. In my head, many of these things go into rethinking the idea of work. Is it only remunerative? Is it only inside a workspace? Is it something that you do informally? Do you only do it within the home? Is it the kind that never gets counted because it is supportive work to the man? Is it done collectively, in the family? In the more urban middle-class situations, is it something that you do only in the formal workspace or only on your computer, sitting in a café? The latter is, theoretically, a space of leisure in which you are actually working. Your work has become so portable you are carrying it with you.

Could you talk about some of the important cultural or economic shifts that have influenced the idea of the ‘working woman’ in the last two decades?

The definition of work perceived shifted after the 1991 census, because of the ways in which the enumerators are taught to ask different questions to women. Up until then, when you were measuring work etc, male data collectors would go into homes and speak mainly to the men, and ask ke aap kya karte ho and he would respond, and then would be asked aapki biwi kya karti hai? And he would say “Meri biwi kuch nahi karti” (“My wife doesn’t do anything”).

Thirdly, since women undervalue their own contribution to work, don’t ask her ‘What do you do?’, because, in all probability, she will give the same answer as her husband. Instead, ask her to describe her day from morning to night, and you’ll get a very different picture.

The other major change was the Anganwadi workers. We had teachers before, but these were working class women, exiting the home, and trying to do something. A certain percentage of these workers realized what it means to keep some of your income to oneself, the sense of respect that brings.

Last year, I was at Kochi Biennale and looking at the ways in which the Kudumbashree women were working [in the Kudumbashree Café]. It is the same thing they do in the home, that is cooking, but the confidence to be out there in the public world, serving people, talking to them – I think all of these have been changing points that we don’t necessarily realise. In the film world, there was this serial called Rajani – the character was played by Vijay Tendulkar’s daughter- and basically, she was a working women, saree pehen ke she would leave the house and was very aware of consumer rights, and was overall vigilant…

I remember people used to use this phrase – “Tu Rajani kyun banti hai?” Was she considered an activist?

She was a kind of an activist. She became quite iconic. So, you started to see some changes through this, even the setting up of things like the craft industry; Kamala Devi Chattopadhyay’s work, Jaya Jaitley’s work which pulled so many women out of their homes into different spaces. When you come out and are interacting with people, it can be very empowering. In factories, too, women were hired and women’s unions created an example. So, all of those things shifted the paradigm a little bit for my generation.

What was your reference point in starting Kali for Women?

The reference point was very clearly what was going on in the women’s movement at the time (1984). The kinds of questions that were being raised, the kinds of activism that was happening, and our own ignorance – of not fully understanding what we were confronting. For example, we were very active in the anti-dowry, anti-rape movements of the time, but the kind of understanding we have of how sexual violence plays out in women’s lives today, we did not have at the time at all. Even so, we had the questions. But, we began to search and couldn’t find much at all, for example, at the time there was one book we could locate on dowry. It was a small monograph with sociological analysis by someone called Stanley Tambaiah. We realized that there was no knowledge. That was the idea behind starting Kali for Women. The idea was to generate our own knowledge and knowledge production, which is also work.

To me it has never seemed like work because it is something I love doing, and the combination of work and pleasure is something that is intense and interlinked…

Speaking of work and feminist afflictions, do you think there is an ethical conundrum in being paid for something that is a political commitment or something you love to do?

I think we have to move beyond this feeling that there is something pure about activist work, and you do it out of a political motivation and don’t need to be paid for it. In a sense, it is also a very middle class notion because it is premised on the idea that your activism stems from your belief in a cause, and hence, doesn’t have to be financially compensated for. But, then, how are you going to live? If you are someone with privilege with structures to support you, you can do it, but there are many people who don’t have that and that is the dilemma…

What do you think your work gives you?

The kind of work I do gives me a lot of things. There is a particular excitement and joy to be in the presence of new thinking all the time. I learn so much from it, it just keeps my mind alive. The kind of work we do also gives me the possibility of change. When I look back thirty-five years, when we started Kali for Women, there were hardly any books by women. I see how much is being published today, and women’s writing is recognised now. I can see that change. You can get into a comfort zone, but you have to question yourself and ask, what voices are being represented? Why? Is that all there is to the women’s movement? The ideas of my generation of feminists are constantly being challenged, and that has to be present in the books we publish. Which means re-thinking how knowledge is produced, re-thinking knowledge, and that means re-thinking your publishing practice. So, after forty years of work, it’s still exciting, and challenging because of all the horizons that you have to negotiate and reach.

You have worked with so many generations of people – what are some of the interesting tensions you find in an intergenerational work process?

It’s interesting because all of those tensions have to do with ways of working together. Feminists of my generation who have been involved with great activist work on the ground, we bring with us an understanding of collective functioning. Our rational minds know that collective functioning is the death of efficiency, because you could be debating endlessly! For me, the first challenge was to explore the possibility of taking that learning, and transmitting it into a work environment where you keep some of the spirit, but don’t lose out on the efficiency and speed of work. So, to think of ways of decision making that could be both transparent and yet there is a point where the buck stops; so they are hierarchical but transparent, there is democracy but with a hierarchy. So, to find ways of doing that, and to resolve in my own mind as you unlearn a lot of your feminist ways of functioning; does that mean you are giving up on your feminism or not? That is a tension.

Secondly, one of the most important assets that need to be shared is the knowledge that you carry, which often remains in your head. You carry the history of the organisation in your head and the workings of it. … So when one leaves, it goes, no matter how much you say you must leave it behind for the next person. You can only leave behind the tangibles. By working with younger people, that has changed.

It is not without resistance on my part or of the senior staff, because all of us are so schooled in our own methods of working, that when you are confronted with the desire to know, and witness the anger that the knowledge isn’t there for them to access—it is very hard.

You realise you have moved into a new generation; that is the first step. You realise that their ways of functioning are very different from yours. You also realise that their feminism is different and that the feminism you grew into has changed, and that you need to unlearn.

The tensions in this process are very high, because the generational tension hits the professional tension hits the personal. It’s tough, but you learn, and it is extremely rewarding when you do.

What does work mean to you? What did it mean to you in your 30s, and what does it mean now?

In my 30s, it meant a job. I knew the jobs I didn’t want, but I didn’t know which jobs I wanted, so when I found it, I thought great! Kaam mil gaya, hogaya. Now, it means something very different. It is a whole commitment to something I believe in, and as I said, it doesn’t feel like work, it is life, which might not be a very healthy situation. Even when I think of what I like to do in my leisure time, I like going for long walks and I love reading! Work and pleasure are closely linked in my head.

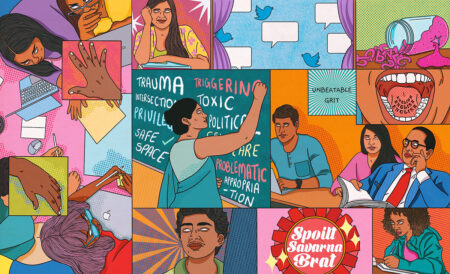

We showed the working women posters to the intrepid girls of Sadbhavna Trust, young Muslim women training to be leaders of their community, and asked them to draw their version of the working woman. Take a look.