The Third Eye: As a filmmaker, how did you arrive at Agents of Ishq? How does it extend/connect to your filmmaking practice?

Paromita Vohra: Because it is 10 years since I made my last documentary, many people ask me, when are you making another film? And to some I answer truthfully, that according to me, Agents of Ishq (AOI) is also a film, a very lengthy film—an infinite film.

The journey has really been to work with the idea of nonfiction and engage with other people’s realities, which is, in some ways, political activity. I will not call it “activism” because it is a kind of political activity—and to that extent all people [practise] some political activity in their work; it should not be exceptionalised. I am uncomfortable when people call me an activist—not from some place of humblebrag, but because I would rather be seen through how I engage with politics through my work as an artist, no matter what the form. In a way, that is what unifies all my work, across forms—my interest in non-fiction and people who are in my films or in the AOI universe, their own personal engagement with the political through their lives or work. And threaded with it the idea of pleasure that animates whatever I do and which is the point of connection to popular culture.

When I started working in documentary cinema, when I was 20, I often used to feel that there is a lot of “in” knowledge. Like history of politics, history of feminist movements. You are assumed to know, if you enter this space—which is very exclusionary thinking.

You enter based on a host of desires, a quest for something. But there is no method to bring new people into this history who may care about something and who might not have full political articulation.

But what was interesting is that I was working with Anand Patwardhan and he is emblematic of a kind of long-term political engagement, which he locates in the everyday. Over the years it has now become acceptable, even fashionable, to critique aspects of those politics; there is something about the everyday that he was engaging with and connecting the dots on—which I learnt something from. But equally, I felt, though then I didn’t have the words, that it was also a schema to which things would often be fitted.

That interaction with the documentary world, which wants to prove something pre-determined like who’s good and who’s bad… my dissatisfaction with that turned into a lot of arguments which were completely incoherent but nevertheless articulate. I remember one colleague saying to me, “You sound like a hysterical feminist,” and I remember thinking, why is she saying this, a dismissal of my critique?

But to return to that sense of observing the political in the everyday—for example, I remember walking home one day and seeing this announcement of a film screening. In Bombay, political gatherings are often announced on blackboards at corners. At the train station, I saw a blackboard saying, “Screening of film at Patwardhan Bagh” in Bandra—Bhaye Prakat Kripala—and I was like what is this, then going off to check it out, seeing it was a VHP video building a justification for demolishing the Babri Masjid, and calling Anand and telling him about it very excitedly (it became a part of this film Ram Ke Naam). For me, it was an education of a different kind, to have a chance to observe politics unfolding in an everyday way all around me, which working in documentary films helped me to do, to understand, and which I would try to bring as a contribution to the workspace, in a young and unformed but intent way.

It was a very different moment in Bombay and there were a lot of unions and networks of activism, so you would encounter many people who you would not encounter in your regular middle-class life. Bombay allowed for such encounters. There was a culture of going out after a meeting or after a protest to an Udupi [hotel] because it was always affordable and near the train station. It was not alcohol; it would always be tea or coffee. It was cheap, you could spend two rupees and you could all sit together and then you became closer to some people and with those people you went to another cheap place to have alcohol. So, there was social interaction, not friendship, but social interaction with diverse people. I was very curious about the elements of this world.

For me, what all these experiences in documentary filmmaking and an extended political world it was part of, opened up was that you can’t actually automatically assume that politics is located in one specific place (or form). I call that the real-estate approach to politics, ki wahan par jaoge to wahan apko politics mil jayega, ya aisi film banaoge to uske andar automatically politics hoga, which is what the documentary film’s base was.

A lot of what you're calling pedagogy, my learning, or my approach to work, started there and a continuous discomfort with the standard documentary form and the way in which we are talking to people, and fixing politics and fixing people—apparently for a pre-existing ‘larger’ purpose. I was uneasy with that.

The shift in cities, from Delhi to Bombay, also informed your filmmaking. Do tell us how.

My first film, Annapurna, was about a collective of women who make dabbas for migrant workers. At 25, I was fascinated by that neighbourhood, where the women from Annapurna functioned—Girangaon, the village of mills as central Bombay was then known. I used to go along for union meetings, and yet I’d say my relationship to the neighbourhood was more sensory than political. The city allowed you to roam in it and discover its histories in a way that was harder in Delhi, especially for a woman, in those years. So that sensory politics developed. I felt, isme kuch toh hai. I want to go and check it out, I want to shoot in the mills, and I want to do all of these things.

What this allowed was a kind of mutual discovery. As much as I was discovering these spaces and these people, I was discovering myself. I wasn't asserting myself as a finished political person who was going to make a film in a certain way and just live out that identity, but [I was] arriving constantly at new political understandings.

I also think encounters with amazing people, like Datta Iswalkar who was a former mill worker [and] union leader, too taught me a lot. Datta … used to come for meetings and I used to hang around and make coffee and try to be useful. One day, I ran into him and he said, “Paromita, tum meeting me kuch bolti kyun nahin ho?” I said, “Mujhe kuch bhi nahin pata hai.” He said, “Tumhe kaise pata hai ki tumhe nahi pata hai? We would like to know what you are thinking and maybe it’ll be helpful in some ways.” That encounter spoke to me. A leader of the mill workers union saying that you must make yourself vulnerable, not take this comfortable position that either I don’t know anything, or I know everything. Try to know by being in the moment, being in the place, being wrong and learning, these are very important things. Datta’s great intellect that I encountered [was] of a very different kind and he helped me understand that a political education need not be dogmatic, but can arise from relationality, experience and conversation.

It was a matter of luck that I encountered all these amazing people who didn’t have black-and-white politics, because they were also doing politics for their own lives, like their own jobs, their own living, their own spaces and their culture—not only performing a liberal self. In some senses, it was an education on equality. How do you be equal with somebody who is very different [from] you? It is not by pretending that you are equal but by trying to find some inclusive conversation that will bring you to the same plane where you function as equals.

With each passing film, that relationship with non-fiction became less and less comfortable, or shall I say automatic. The truth of the matter was that I was taking from people’s reality to say something that I wanted to say, to express something about myself and I thought a lot about how this is not a simple business. By the time I came to Agents of Ishq, there had been all these years of thinking about how do we engage and with whom and how can the inherently joint nature of the enterprise shape the forms we create—all of this shaped some of the methodology of Agents of Ishq.

What was the nature of your engagement with the feminist movement and how has that contributed to the setting up of Agents of Ishq?

With the feminist movement, I won’t say “my difficulties”, but some of the things that I struggled with was this feeling continuously, that it was very sober. When I was young, I found it too—now I would use the word—respectable.

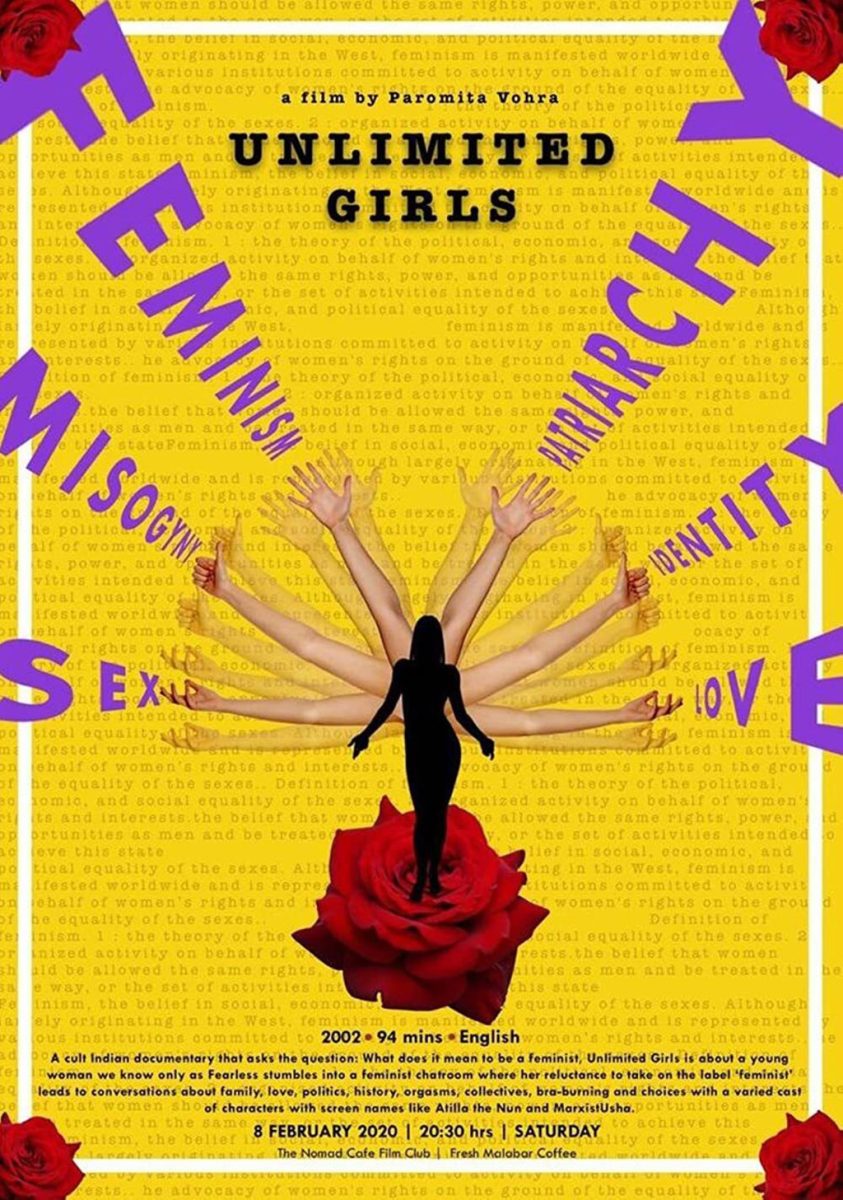

And I mean, yes, there was a lot of sisterhood. The sisterhood is fun and people dancing at parties and all of which must have been great for a generation that was breaking [away] from certain ways of being, but I did not really relate to it much. I just felt like it’s not an easy space for many different types of people to enter. So, for me, the making of the film Unlimited Girls was the first time I entered the space on my own terms, so to speak.

Unlimited Girls had the chat room as a device, in which feminists had conversations about themselves. Why did I use a chat room? Because I was, of course, nefariously spending all my time in chat rooms, doing unholy sexual things. It was very much part of my zahan, my being, at that point, and in retrospect, a space that I felt allowed a non-verbal politics about my idea of myself to be rendered. And because I was thinking, yes, the women I was shooting want certain things to be stated in the film. Also, I had read many minutes of feminist meetings and conferences that had taken place over the decades and they felt like a long conversation, of people thinking a politics together over time.

How should I do it in a film? How to make the politics explicit in a way that does not make the film literal or pedantic? And then the two things got married in my head—my personal sexual explorations in the chat room and political explorations of feminist conversations, were not reflections of each other, but were in interplay, illuminating each other, a way of understanding something—theory and experience illuminating each other.

Those negotiations between characters in the chat room create a richness, and the chat rooms become inclusive frames because they allow different people to come together and put a little bit of each on the table. They also allow people to be at odds with each other, while having overlapping areas of agreement. It’s an inclusive frame which is not conformity-driven—here the individual and the collective don’t become identical or equated. Rather they shape and reshape each other, converge and diverge. That really began to shape everything I did.

I would say my work is the search for non-binary forms for a non-binary politics.

I also did feel like the feminist movement did not have space for sex. That it was considered, what is it called—“sleazy”, right? You could not easily talk about pleasure and enjoyment. Enjoyment was not there. I used to get a little bit bored by that. And then I went to the CWDS (Centre for Women’s Development Studies) exhibition of women of India from 1875 to 1947, which was impressive, but it was extremely alienating for me. I come from a family of uncommon women. My grandmother was an actress, she was a film producer, but she was not famous. She was no Devika Rani! I did not feel that what I had seen around me—not the binary of victimhood or achievement but the granular adventures of uncommon lives which accumulate to make shifts over time—was represented there and I did not understand why it was not there.

A lot of my dissatisfaction was a criticism with the absence of intimacies. It was something I loved, feminist politics was something I loved, it has shaped my life and so much, but I also felt like yeh cheez kya hai?!

When Unlimited Girls came out, I was very scared that all the older feminists will come and make chutney out of me. I didn’t sleep for many nights, but many like Sonal Shukla, who was quite sceptical of me during the filming, came to see the film and when she left, she said, “You really made the film about us.” So, there was also that in the feminist movement: a lot of capacity to recognise when you did something meaningful, and I valued it. My learning over time from that was that it is possible for people who don’t fully agree, to be critical of each other, but also to be loving to each other. It is very possible. When we are young, we complain that older people don’t take us seriously enough. But those feminists did not really have a reason to take me seriously, did they, just because I had feminist feelings? So even my expectation that I should be taken seriously softened, or deepened, lost its petulance. Spaces they had made were spaces I inhabited—and my expectation that personally a place must be created was childish. My growth had to come from my own quest as I traversed the spaces they created, comfortably but also critically, perhaps added questions to their questions and so extended that conversation—and that growth did come through this individual striving in a collective space. In doing, and doing, and persisting, and then also being embraced, not by everybody—many people disagreed with things in Unlimited Girls—but on the whole, their recognition that I’m deeply invested in this politics, was a loving recognition. It created the grounds for many conversations, thrilling agreements and productive disagreements.

How did you negotiate all the conversations, discussions, activism on violence and rape in the move towards talking about pleasure?

When Agents of Ishq was [launched], it was with the kind of frustration at much of the conversations post the Delhi gang rape case. There were all the protests and I had that feeling, not the irritation with “hang the rapists”, woh toh expected hai from certain sections, but actually my irritation was at the conversations about how the public space is dangerous for women.

The politics of the Seventies and Eighties, the anti-rape struggles, came into mainstream consciousness in 2012 in a certain way. For example, say, the Creep Qawwali, which AIB (All India Bakchod) made, or East India Comedy’s self-regarding video saying, “I’m sorry, if I could get the rapists, I would like to pulverise their testicles.” Then there were these videos about how the teacher is secretly reading pornography while telling the students not to study the reproduction ka chapter—but that teacher was always portrayed as a provincial man—so it served to enhance the stature of the woke bro, rather than create a political discussion about sexual culture.

Inside these conversations, there is a deep kind of purity politics and sanitising of caste. My understanding of caste grew in these last 10 years, from seeing all of this. Before that it was more theoretical. I learnt how caste and feminism ka ek ajeeb cocktail jo ban jaata hai in these conversations. That I understood in the way in which so much of all these videos were praised because they supposedly took the side of women and were always about protecting them (who was protecting them from whom?), rather than talk about women’s freedom—while assigning men of marginalised backgrounds as the threat.

There were also clear indicators of the way middle-class women were becoming: “I have to protect myself. I must be protected rather than being adventurous.” I mean, look at the adventures I had in this city. One didn’t really think about it too much then. But in the classic area of adventure, you went to a new place, you roamed about, you took the wrong bus, you had regrettable romances. But you had a lot of fun and a lot of disasters. So much was learned from that experimentation, a strong sense of what I want and don’t want, what is fair and not fair. But now people are not wanting to step outside that safe space uske andar reh reh ke hi jeena hai. The demand for justice and freedom are very different from saying the world should be risk-free.

I also had an irritation with people, always mocking those who are ignorant or incorrect, but never giving the information that will help them. In a way, like me wanting to know about feminist things but having nowhere to find out, and then being mocked or looked down on, because I might have said something wrong. When Agents of Ishq started, there was an understanding that, okay, we want to talk about sex as we want to give sex education, but we want to do it in a way that’s pleasurable and fun and we wanted to be inclusive and helpful, not prescriptive and condescending.

How did you imagine AOI? Were you clear about how you wanted the website to be?

We thought a lot about the aesthetics of AOI. How should it look? It should look friendly. How do people around us talk about sex? Either as violence or difficulty in the mainstream media. Or people talk about sexuality, but not sex in academic and NGO-ish spaces. Or it’s in pornography which is not really a beautiful space—quite apart from whatever critique you may have of it.

We felt this website should look friendly and beautiful. It should look handmade, with a sense of touch, not clinical or technical. Like there is a set of human beings who are infusing their desires and feelings into the work. Not like this modular, generic information that is handed out on the internet. That feeling that main andar aa jaa sakti hoon, no matter who I am or my level of experience.

What is so interesting is that the day after Agents of Ishq was launched, everybody was calling up and wanting to interview us and people began writing to us. I have a screenshot of that first inbox full of emails with the subject: “I too want to be an Agent of Ishq”. So clearly the idea of being an Agent of Ishq was very persuasive for people. But more importantly, they determined the definition of what that meant, since we did not mandate any meaning for it, and brought those definitions and energies and feelings to the project—thereby reshaping the project, co-creating it.

Agents of Ishq grew into an archive of sexual narratives from diverse backgrounds, which do not fit in any category. They are very much about people recognising that sex itself is the education, that your lived intimate experiences are your education—that becomes a shared common wisdom that people add to and take from. In that sense, the form of the chat room, which attempted to mirror diverse feminist engagements, is rendered in the digital lived form through Agents of Ishq, where diverse experiences around sex and sexualness shape the discourse around sex, rather than just fit into a pre-existing curriculum of sex and relationships that are arranged around a schema of progressive or regressive. As there are diverse iterations of feminism, drawn from contexts, so there are diverse iterations of liberation via sex, drawn from diverse sexual contexts on Agents of Ishq.

Agents of Ishq emerged from a deep engagement with your own practice, experiences and questions with documentary filmmaking, trade unionists and the feminist movement. Now, seven years after starting AOI, how would you define the nature and the shape this digital platform has taken?

In Agents of Ishq, there is an aesthetic frame that is more important than the informational frame. The idea is to tell people that you can be who you are, it is okay to be confused, and let us talk about these things. But to be honest, I do not think even we fully articulated what that “let us talk” meant, because it is a common thing to say within the sex ed space. In the give-and-take between people who have written for AOI or have done numerous things for AOI, we also changed, we learned and are still learning. It is a mutual change project.

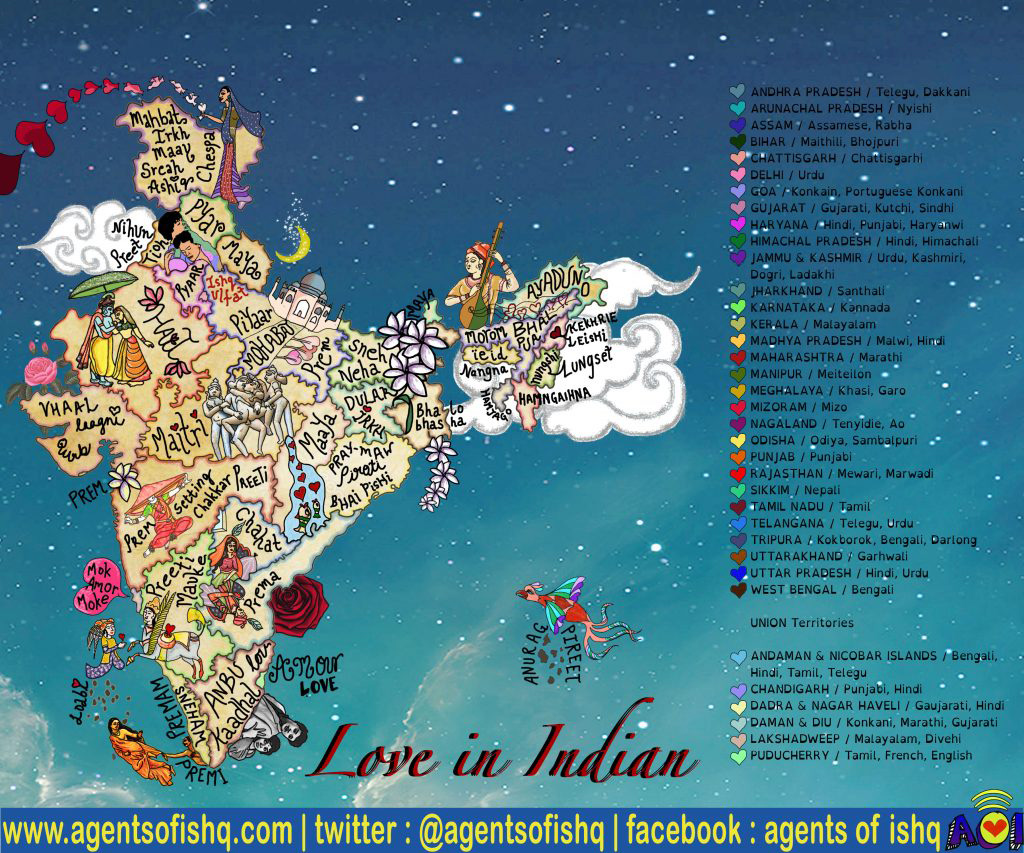

Seven years down the line, I can say in precise terms what the methodologies are, but they evolved over time in tandem with the audience. One key element is that AOI is a big project related to language.

What is the language in which we speak about ourselves?

We work with the concept of dynamic agency, which means that we are not telling you what is the right thing for you. We are just saying what will strengthen your internal muscles so that you can gauge what is the best thing for you in any circumstance.

For example, many NGOs work with girls to build their leadership so that they will stop child marriage. But girls are saying, “We cannot fight that fight. We want to fight other battles, like wearing jeans, having a mobile phone, going out, finding love in whatever way. We will do it bit by bit.” For some marriage might be something they even seek. And I feel like that mirrors even my own life—when I told my dad that I want to move out and live on my own at the age of 22, he did not say no. He said, let me think about it. Then he was thinking about it for so long I thought I’m just going to do it. And I did it. What equips you to do that? What mixture of context and desire? That is really what we are engaged in.

It is also a stealth project about how do I define what it means to be Indian, because the way that we work with language is very much to try to not have a pure language. Although we do everything in Hindi and English, it is only because it’s our language skill set, like I know Hindi. We are not doing it in Kannada or Tamil or any other language. Somebody in those language cultures should do their own rendition of an Agents of Ishq. Yet, within English and Hindi too there is an effort to have that heterogeneous language. I have a friend who calls what we make “sweet didacticism”. It is didactic, it has a pedagogical purpose, but it’s with a certain sweetness.

Also, quintessential South Asian ideas are used for interactions, like the concept of apnapan, which is important to me. When you enter the space, it should give you a feeling of hospitality/apnapan. Be at home, have some fun, nourish yourself. We are serving things to our audience in that kind of a way. It is not a scolding project that we will tell you what you lack, but build on what you have with what we have to create a more pleasurable and resilient world, personally and politically. The shape of the project is fluid and open to change while holding fast to its feminist centre.

What do you ask yourselves before you decide this is an AOI piece or not?

The methodology of creating something is that before we make any piece of content, there are only two questions we ask—Is this going to be helpful? And how are we answering a question in people’s hearts that they may not yet have asked yet? This is a good compass for us. Periodically, we ask questions of the audience to try to understand what the audience is feeling, not what they are interested in getting information on. It is about a continuous observation of the audience and periodically sitting down and just talking about the different feelings that emerge.

People who write to Agents of Ishq also determine some of our content. For example, a lot of pieces that came in would often be about feeling vulnerable, or the need for touch, but touch having become so contentious, post-Me Too, especially… How then should we find a way to talk about it that will not fall into that binary?

Feelings, not information, drive all our content. That automatically creates the frame that is inclusive, in the sense that it allows people with different levels of experience to enter and interact comfortably. There is no hierarchy of experience and there is no hierarchy of a better sexuality or lesser sexuality.

Even in terms of having people who are not primarily English speakers enter the space—evolving a methodology of how that language will play out in short sentences with no complex sub-clauses type of writing.

Also, importantly, AOI is about experience; it is not in a problem-solution frame, but rather looks at journeys we are making as sexual people, what we need to make those journeys possible—safe, pleasurable, meaningful, autonomous, yet collective. AOI pieces are also rooted in Indian contexts. And they should not use jargon and or diagnostic language like “problematic” or a superior tone. The pieces should have a spirit and language of sharing. While we aren’t looking to create literary writing, we do want the pieces to be as beautiful as possible—in the writing, the thinking, the illustration. Because we feel art dignifies human experience rather than turning it into cultural clickbait or political fodder.

We also did a sort of needs assessment early on from which an interesting learning emerged. People speak about certain topics (gender-based violence, for instance) in public, some they speak about only in a small circle (say, menstruation and relationships), and some things they never speak about to anybody—rejection, heartbreak, fantasy, desire. We thought, they don’t need us for what they are speaking about in public. They are already doing that. And that is even a pretend part of themselves, but this personal and private space, let us make stuff that nourishes those parts of them.

As a result, we build a lot of materials that do not require people to say anything about themselves. We do not want to make people vulnerable or declare their identity as if they are part of some progressive sexual army! How can they figure out their own relationship to these politics in their own time and not be forced into conformity in the group?

We also have a lot of things which you can read alone, like a personal essay or poem. Our films or artefacts that are consumed in a group like, say, Mai Aur Meri Body or Consent Laavni, do not require people who are consuming it to speak about their own private self. What happens is they discuss the film, debate the scenarios and in that they discuss themselves but with enough safety. Traditionally this is what art has always done for people.

How do you get people to write and contribute to AOI?

We don’t actually solicit any pieces—though at first we did seek out a few. But mostly people send them on their own: they decide what they feel is an AOI piece, which is in itself very interesting. On the whole, we don’t get pieces that are typically in the trauma-healing binary that governs sexuality conversations. Many people want to talk about their life. Sometimes we suggest to them not to write their names, not say certain things which would make them vulnerable.

We had not expected to receive personal narratives and when they started coming in we had to think on our feet. Over time, we evolved a method of doing this.

Only a few people who send in their narratives are good writers. Many do not even really know exactly what they’re trying to express. Therefore, it is an elaborate, back-and-forth process. Some people send fully formed essays. Other people sometimes send us two paragraphs and there will be those three or four lines that are interesting. Then we will ask them a question. They send us something, we do some edits and send it back and this can go on for six months at a time. It can go on for two weeks or a year. So, it’s an editorial process but also a kind of conversation through that process of them understanding what they are trying to pinpoint.

Sometime ago, a boy wrote a piece full of big words marked by absolutes and condescension about everything. Basically, he had met somebody online and only had a WhatsApp relationship with them, leading to heartbreak. When we wrote back to him asking a few questions, the new draft was just the opposite. It was vulnerable, open and unsure. In this back-and-forth process he wrote to us at the end saying, “Well, my heart is still broken but I think that WhatsApp love is still true love. And anyway, while writing this article, I came out to my parents.” This happened with many people, they either came out to their parents or moved out from living with the oppressive boyfriend, taking their own journeys and reflecting on themselves in this process of being asked questions while being left alone to write on their own.

The aesthetics of AOI draw heavily on popular culture. They are not driven by the tone and texture of either the development world or the world of education. That is a clear choice you have made.

The project has its own hardships because it does not want to belong in one space or the other. I cannot say that it is a true-blue, popular culture project—it’s not commercially driven. But I do think that it fulfils many qualities of popular culture which has been a great teacher—for the project and for me as well.

You know, it’s very funny, but my grandmother was a film producer, her company was called Variety Pictures. And I, always think back on that word “variety”. Look at the Hindi film, it is variety entertainment. Variety stands for heterogeneity of all kinds of tastes, all kinds of feelings, all kinds of registers—that is important to have in one place because everything else becomes homogenous, conformist, segmented rather than interconnected. And whatever is pushing you towards conformity is just indoctrination. It is not really an education that equips you to at least find your way, go a little bit in life until you come to a new quest.

One of the things about a curriculum is that it decides both, what is necessary and what is appropriate and then circumscribes the understanding of the field to that—telling people what they need to know rather than what they want to know. That’s why I think of it as a colonisation process and with sexuality it also creates these elites who then police the cultural landscape, sorting things into problematic or non-problematic, “normal” or not normal behaviour, constantly sanitising and homogenising it while seeming to uphold rights—but that’s not the same as the political project of freedom.

With a pedagogical impulse drawn from popular culture there is no real curriculum—the topics are decided as per what people need or feel like they want. Should we be speaking about polyamory or vaginismus? Is heartbreak part of sex education? If we think about it as a learning and development of our intimate selves (not even intimate lives) then it is culture— popular or high art—that we go to for this education and making sense of our experiences. It’s just that it can be very unmoderated of course. So in a way it is about learning a way to be free, or free-ish, i.e., to become oneself in tandem with communities. Using cultural forms—framed in pleasure where we define pleasure as that which makes us feel good, including a good cry) — provide this kind of discursive educational space. And AOI perhaps draws a part of its pedagogical logics from these thoughts.

This kind of heterogeneity allows you to formulate and explore new questions for yourself. They are not part of a syllabus indoctrination. We do not want to replace an old normal with a new normal. The references to popular culture create an inclusive frame of reference, but on its own too, AOI would like to be a part of the popular culture as well.

What does success feel like for the Agents of Ishq?

You can either go by the numbers as an indicator of impact and success, or you have to go by something else—the way people engage with your content. It is more interesting to see how many people are writing, how many people are beginning to use your faltu hashtags on their own. Like Thirakta Thursday might land up somewhere else, like Bore Mat Kar Yaar lands up somewhere else. The internet also has this tripartite structure. There is a public in the comments where people write; there’s a personal, where they’re sometimes sharing in a story and sharing with their friends. And there’s a private where they’re sending you DMs. People express love quite a bit online. There are people who write us messages like, “Agents of Ishq, have I ever told you I’m proud of you?” Or people will write, “I wish you were the big sister I didn’t have growing up.” And it’s really about learning to trust that response and not get sucked into the numbers.

The engagement of people in the discourse through their contributions and the number of collaborations we do is what we use as an indicator of success.

How much people plagiarise has always been a good indicator. The internet’s special kind of plagiarism, where you can pretend it was your own idea because you saw it somewhere, but nobody knows you saw it then, but that is also an indicator that you are actually reaching an audience and the audience thinks it’s important for them. We know that AOI has helped shape the language, aesthetics and many new focus areas in discussions on sexuality and we count that as a success.

As people who create ideas online, how do you negotiate the ever-changing algorithms?

The algorithm is crushing, of course, but you can continuously attempt to hack it. All algorithms can be hacked. Because it is like this, if you fall in love, you hack the social algorithm, right? You are supposed to fall in love with your type, but you do not, you fall in love with some other type altogether. And that starts creating something volatile and changing things. Any popular culture medium means that you are going to be forced to engage with people, not in terms of identity, but in terms of experiences, as experiences bring us all into an equal frame.

All the social media that we are using, which are like A-list social media, right? Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, these are somewhat elite and they’re elite because they push everything towards homogeneity, but the reel itself is not a dogmatic form—the way in which people pick up on nonverbal communication, which is not didactically spelt out for you. It must have confidence that people are able to do that. Popular culture has a little bit of that confidence, but a lot of the educational culture that we have does not have that confidence in people and in open-ended communication.

Has Agents of Ishq had interactions with schools and teachers? What has been the response of the formal education system?

There are teachers scattered all over who are really trying to help their students, and so they reach out to get this material from us. But, in schools, sometimes there is a response to social moments where teachers feel like you should come in and talk about consent. There’s a lot of gender warfare that schools and colleges find hard to deal with and they want us to come in. What we have found difficult is a spirit of co-creation. We cannot create materials for those spaces unilaterally because the person who inhabits that space knows it best. That same logic of dynamic agency also applies to teachers, right? They know what can be done and what can’t be done.

But is that connection even desirable? Because the moment you start talking about things like body, experience and emotion, formal schooling struggles.

The entire approach to education would have to change for such things to happen. But what is possible is that maybe only some elements of what we do can enter that space. It is not our goal to incorporate the whole thing into a school curriculum This idea of the life-world, which forms also the basis of what we are doing, is a swelling mass of influences, and that the individual themselves is intersectional and is made up of their emotions, their physicality, their social identity and their biography. So, the popular space or the space of culture is an educational space of a different kind. And it provides a kind of personal education that people go through—sometimes it is within groups, sometimes they do it individually and sometimes it enters that kind of public formal space.

Did you ever imagine you would be an educator? It’s not a sexy identity, not as sexy as a filmmaker.

Well, you know, the sexy teacher is a thing, but I’m not that thing. Uh, no, I mean, I still don’t actually see myself as that, but I recognise that certain amount of that happens in what we are doing and it’s always been there.

I just see myself as an artist actually and art is also about educating yourself. An education of the senses, and without educating our senses, we cannot hope to live or reflect on our learnings from life. Because it is our senses that see us through the world. And the purpose of art is for that sensory knowledge to be continuously consolidated, destabilised and restabilised.