“So, which country’s laws apply to these LGBT people?” a senior journalist asked me over a phone call. He works with a prominent Hindi newspaper in Patna, Bihar. I had called to invite him to an LGBTQIA+ media workshop that my publication queerbeat, was co-organising in Patna, in February 2025. Titled #ReportItRight, the focus of the workshop was to train reporters and editors working in Hindi media to accurately and sensitively cover LGBTQIA+ communities.

I told the journalist that LGBTQIA+ people were like anyone else.

That they were present everywhere, in every culture including India; that the same laws that apply to him, applied to them; and that queer people may need some additional legal protections to safeguard them against the discrimination and violence they face. “Okay,” responded the journalist.

Although his question had implied that queer people are some sort of a foreign body, I wasn’t surprised to hear it. As a queer journalist with 15 years of experience in the news media, I am aware of the historical under-reporting and misreporting of people with LGBTQIA+ identities and their stories.

His question did made me think about where the conversation about queer people lies in the media, particularly Hindi media, in 2025. The situation might be similar in other regional language newsrooms, but I will restrict my comments to Hindi and English media because those are the only two languages I understand.

That journalist eventually didn’t come to the workshop, but 48 others did. The participants were a mix of senior and early-career reporters working in print, video and digital newsrooms in Patna, along with journalism students from the city. About 50 percent of the participants were women. I was thrilled to see a trans woman reporter in the group — an identity that continues to be under-represented in Indian news media. The room was packed.

Supported by the High Commission of Canada in India, this was the second LGBTQIA+ Hindi media workshop that queerbeat had facilitated with partnering organisations. Along with the participants and myself, my colleague Saurav Verma (who is a gender and sexuality educator) dissected current media coverage of queer communities, explained key LGBTQIA+ terminologies and discussed queer-affirmative language.

The Patna workshop reinforced what my team had learnt in the first workshop: that while covering queer communities may not be a priority for many Hindi media outlets yet, a gradual positive shift is underway. They are paying more attention than previously, to stories about LGBTQIA+ communities.

They recognise their own limited skill and vocabulary in reporting accurately and sensitively on these communities. We heard from the reporters themselves that media training workshops are the easiest and fastest way for them to pick up the right skills and language to make their reporting queer-inclusive.

“I think there is a lot of interest in readers to know about the lives of queer people, but as reporters we struggle to find new angles and stories about the queer community. A training on how to find such stories is helpful so we can keep the conversation on queer issues alive,” said Juhi Smita, reporter with Prabhat Khabar in Patna.

Agreeing with Juhi, Rachna Priyadarshini, a Patna-based freelance journalist said, “If we want the conversation about LGBTQ+ people to improve in our society, the media narratives about them need to improve. Currently, many reporters and editors don’t even know the difference between various LGBTQ+ identities clearly. We have a long way to go.”

The fact that younger reporters were the most forthcoming and engaged in these workshops is a positive sign for the future. It points to a growing interest in the media to cover queer communities responsibly.

Queerness as a beat

- Difficulty in finding LGBTQIA+ sources who can participate in stories and experts who can explain the issues on the ground with context

- Difficulty in finding new and diverse stories — and different story angles to report on known issues

- LGBTQIA+ people refusing to talk to journalists

- Confusion between basic terms related to gender, sexuality and LGBTQIA+ identities

- Fear of offending queer communities

- Absence of newsroom guidelines in Hindi on how to cover queer communities

I often tell reporters and editors that most of their challenges related to finding diverse LGBTQIA+ sources and stories can be addressed by a simple reframing. Instead of event-focused coverage of queer people when a court judgement is delivered, a protest is organised, or something tragic happens a queer person, they should treat queerness as a beat. Just like healthcare, education or politics.

A reporter covering the healthcare beat will routinely visit hospitals, talk to patients and build strong relationships with doctors and researchers across disciplines and hierarchies in the medical sector. They will meet representatives of the NGOs working on healthcare, government, pharma industry and so on. It is only after doing all this for years and persistently demonstrating genuine interest in understanding healthcare, that a reporter develops true expertise in that beat.

The best stories come to reporters after they have earned the trust of their sources.

In the workshops, when reporters complain that queer people don’t talk to them, I ask, what have you done to earn their trust?

People come out of the woodwork to offer leads if they believe they can trust a reporter with their stories. As a reporter, I have experienced this myself.

However, most newsrooms and reporters do not consider queerness a beat worthy of dedicated attention, resources and rigorous reporting. Reporters often expect queer people to offer their stories on a platter. Why should they? In journalism, the power dynamic between the newsrooms and sources — particularly if the sources are from marginalised communities — is deeply unequal. The onus to reduce this gap is on the powerful — the media. The reporters who work hard to bridge this difference end up with the best stories.

We are beginning to build this queer beat. It is both, a challenge and opportunity.

A reporting approach that incorporates their reality goes a long way in building public understanding of queerness — and natural disasters.

Limited or inaccurate understanding about queer lives

In Hindi media workshops, we spend quite a bit of time discussing the inaccurate representation of LGBTQIA+ people in the media, so that reporters and editors can avoid these mistakes in their own reports.

We start by asking the participants basic questions, such as: What do they understand by the terms ‘trans’ and ‘intersex’? What is the difference between sex and gender? What are the gender roles and expressions they see around them? We find that most participants don’t know the difference between a trans person and an intersex person. Some say a trans person is a “shemale”. One senior reporter collapsed the entire spectrum of LGBTQIA+ identities into a single term: ‘tritiya ling’ or ‘third sex’.

The reason for this lack of understanding is that the stories of LGBTQIA+ people have historically been ignored by newsrooms. Further, many newsrooms have been complicit in perpetuating queerphobia in their stories.

We explain several key Hindi terms related to LGBTQIA+ communities so that the journalists can get their basics rights. All these terms are compiled in a Hindi LGBTQIA+ media reference guide that queerbeat co-created with support from the Inqlusive Newsrooms project, funded by Google News Initiative. TARSHI, a Delhi-based NGO, has also compiled a similar glossary of terms related to LGBTQIA+ identities and sexual and reproductive health rights.

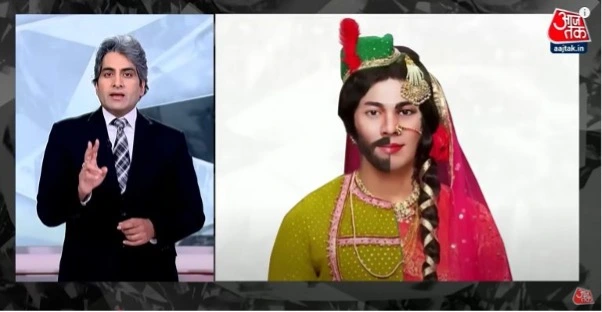

Then we discuss stereotypical representations of queer people in the media. One common queer stereotype is portraying queer people, particularly trans women and gay men, as oversexualised beings. In our Patna workshop, we played a video clip from a YouTube channel based in Bihar, of a male reporter interviewing a kinnar in a small town. The clip is packaged in a highly sensational manner and the reporter is constantly asking her questions about her sex life. “How do you do sex?”, asks the reporter repeatedly during the interview. The kinnar’s discomfort is palpable, but the reporter is hell-bent on knowing everything about her sex life.

One wonders: what public purpose is served by broadcasting this information?

While discussing the problems with the video clip, we asked the participants to examine the roots of this voyeuristic cis-heterosexual gaze. Such discussions help journalists and newsroom leaders to reflect on the biases they carry and perpetuate. “The workshop helped challenge my misconceptions about the queer community,” said Vimlendu Kumar Singh, a journalism student at Patna University. “I think I understand the community better now and they deserve to be treated equally.”

Another pattern of misreporting in Hindi news reports is the use of deadnames of trans people. Here is a headline: “Pyaar main pad kar, operation karwa kar, Rahul se ban gaya Ragini, shaadi bhi kar li. Lekin phir mila dhokha (after falling in the clutches of love, Rahul became Ragini, got married and then was betrayed).” Not only the headline, but the entire report constantly refers to the person as “Rahul se Ragini bana shaks (the person who became Ragini from Rahul)” and blames Ragini for what happened to her — without questioning the person she was in love with and the police administration who became involved later.

We have found that most Hindi journalists and editors don’t know what a deadname means, or that using it disrespects trans people.

There are other kinds of misreporting as well. Sometimes, in news coverage of crimes where the suspect is a queer person, reports will include the suspect’s sexual identity, even when their sexual identity had nothing to do with the robbery or the murder. Have you ever seen a news headline saying that a robber was a cis-heterosexual male? Why are queer people’s identities used as clickbait? Such biased and sensational reporting is a disservice both to LGBTQIA+ communities and readers.

In fact, the media should be extra cautious in protecting the identities of queer people in their reports. To illustrate this in workshops, we talk about over-explaining the potential harm to vulnerable sources. This suggests it is the journalist’s responsibility to go the extra mile, explaining all the potential ways the story could harm the queer person if their identity is revealed in it. The news clipping could end up in their family WhatsApp group, for example. We suggest doing this as standard practice, even if the queer person easily consents to their identity being included in the story. Sometimes, the person themselves may not be aware of the potential harm.

Amir Abbas, CEO of Democratic Charkha (a digital media organisation serving Bihar and Jharkhand) gave us an example of this. In 2022, they published a love story about a trans couple in Patna. Although the trans man had given consent to reveal his identity in the story, when the story was published, his employer fired him. The employer had previously been unaware of the trans man’s gender identity.

Systemic issues

A big root cause of the under-reporting and misreporting on LGBTQIA+ people is the lack of queer people in newsrooms. In Hindi newsrooms and especially in leadership positions, the problem is even more acute. This influences what kind of stories are told, how they are told, who gets to tell them and who gets covered.

My queer journalist friends working in Hindi media tell me that their newsrooms are still not a safe space for them to come out. They hesitate even when pitching queer stories to their editors, fearing that they might be perceived as queer themselves. Sometimes they have a half-baked story idea and are looking for a senior person in the newsroom who can guide them. When they don’t see anyone like them in leadership positions, they sometimes kill the idea themselves, thinking that their bosses wouldn’t understand. If they do manage to present the idea, their editors often do not understand how to approach the story, resulting in superficial coverage.

This scenario would play out totally differently if queer people could openly occupy leadership positions in newsrooms. Not just queer journalists, but all journalists would feel empowered to take their pitches about queer issues to those editors, knowing that they would be able to see the story’s potential, place it in right context, and provide guidance if the report has flaws.

In a 2023 online survey conducted by my organisation queerbeat, 82 percent of participants said that the coverage of queer stories in the mainstream media do not reflect the diversity of issues in LGBTQIA+ communities.

queerbeat is able to consistently tell underreported, diverse and intersectional queer stories because many of our reporters are queer themselves, or come from historically oppressed communities. We have written about queer aging, nonbinary gender transition surgery, the loneliness of asexual communities, queer Christians reconnecting with their churches, queer sports clubs and queer teachers trying to make their schools safe and inclusive. We present such examples in the workshops to show that these stories are possible.

Two things have become clear to me after conducting LGBTQIA+ trainings for Hindi media outlets:

- The understanding of LGBTQIA+ identities and issues in the Hindi media is poor.

- Journalists, particularly younger ones, are eager to learn, so they can report accurately about LGBTQIA+ people.

This highlights the need for more such media workshops in Tier II towns, where the public conversation about queer people needs a bigger push. “As a journalist reporting from the Hindi heartland for over a decade and a half, I can say that these trainings don’t just fill knowledge gaps; they challenge deep-rooted biases, foster empathy and build a culture of inclusive and responsible journalism,” said Tabeenah Anjum, a senior journalist based in Rajasthan. Tabeenah was a participant in Inqlusive Newsroom’s media workshop in Jaipur in 2023.

The feedback we receive after these workshops encourages us to continue doing them. “The workshop expanded my understanding about the diversity in the LGBTQ+ community and the range of stories that can be done about them,” said Sunny Kumar, a journalism student at Patna University.

Another participant, Vyas Chandra, a senior correspondent with Dainik Jagran said, “The sessions on LGBTQ+ terminology and affirmative language were particularly useful because they will make our reporting and communication about queer people accurate. Such workshops should be organised regularly so that we keep learning.”

One of the participants in our February workshop in Patna was Priti Prabha, a freelance reporter who contributes to BBC Hindi and other publications. Before coming to the workshop, Prabha had been searching for a transgender couple in the city, to tell a story about their life. Weeks had passed with no success. “I was feeling discouraged, and had come to the workshop looking for solutions,” Prabha later told me. “The training on interviewing techniques, building LGBTQ+ sources and earning their trust by persistently showing up, gave me confidence.”

Prabha returned to the field and knocked on more doors. Finally, she not only found a trans couple but also discovered an under-reported angle to tell their story: the couple is asexual. Prabha’s lovely story helps shift the focus away from the oversexualised representation of trans people in the media.

TTE-queerbeat Fellowship Announcement

Right now, the lacuna of accurate and diverse queer narratives in the media — particularly in non-English publishing — is huge. The fastest and the most effective way to bridge this gap is through collaborations between knowledge outlets and training writers. For this reason, queerbeat and The Third Eye have launched an initiative to mentor young Hindi writers. After a careful review of applications, we are thrilled to announce our two fellows:

Hari Om Srivastav, a community educator and artist who works with Rafooghar on their Meethi Biradiri project, to redefine vocabularies around queerness and gender.

Imran Khan, a writer who investigates the challenges of writing stories of marginalised communities through a queer lens.

-

Ankur Paliwal is an independent journalist, and founder and editor of queerbeat, an award-winning media and research venture that is building public understanding of queerness in India. Before starting queerbeat, Ankur was travelling across India, as well as east and west Africa, reporting longform and investigative features on science, health, gender, sexuality and the environment for various publications including the Guardian, Nature, Scientific American and FiftyTwo. He has a Master’s degree in science journalism from Columbia University in New York and lives in New Delhi.